A century and a half after his death, the Native American leader's vision of finding peace and prosperity in a divided country is more compelling than ever.

-

Spring 2021

Volume66Issue3

It is possible to walk down a rough, rain-lashed street in Seattle and stand near where Chief Seattle, the city’s namesake, delivered a speech considered to be one of the greatest ever given by any Native American. But you will be alone in your effort, and won’t find a statue, a sign or even an ‘X’ to mark the spot.

Seattle is the largest city in the world named after a Native American, but most city residents would be hard-pressed to describe him. Ironically, much of this is due to the debate surrounding the famed speech that he gave in 1854, at a time when his people’s numbers were dwindling, and to an audience that included the Washington Territory’s first governor. Not printed until 1887, the speech has taken many different forms over the ensuing century and a half, evolving from a paean of peace and territorial sovereignty to its more recent rendering as an environmentalist anthem. After all these years, the question remains: Which version of Seattle’s speech is the true one?

When Seattle died on June 7, 1866, he had been exiled from his town for over a year, driven out in an effort to spiff up the place’s rough image. At his death, neither of the territorial newspapers mentioned his passing, that of a Native leader who, on February 28, 1856, had been quoted on the front page of the New York Herald’s morning edition.

The town’s name kept his memory alive, but the question “Why would you name your town after an Indian?” was more an accusation. In 1875, a popular travel writer, Charles Nordhoff (grandfather of the H. M. S. Bounty trilogy’s co-author) wrote: “When… you enter Washington Territory, your ears begin to be assailed by the most barbarous names imaginable.” After citing “Skookum-Chuck…Nenelops …Toutle.” He added, “Seattle is similarly barbarous.”

The man himself did not escape similar derogatory criticisms. In 1890, western historian Charles Bancroft described him as a “naked savage who conversed only in signs and grunts.” The same disdain has prevailed. In his 1978 biography, Doc Maynard: The Man Who Invented Seattle, Bill Speidel writes that when speaking, Seattle “sounded like a demonstration by the winner of an Iowa hog-calling contest.”

In his speech, Seattle welcomed Washington Territory’s diminutive first governor, Isaac Stevens – also known as “Little Rough and Ready,” or, depending on your politics, “Little Bandy-legged Tyrant”– when he arrived in the newly named town on January 10, 1854. A West Point graduate and veteran of the Mexican War, he headed the Northern Railroad Survey, was Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and a leader of the Democratic Party. After visiting a nearby coal mine the day before, Stevens told Seattle residents that their town, as the terminus of a transcontinental railroad, would become another London or New York.

The next morning, a thousand Indians who Chief Seattle gathered at the waterfront heard Stevens describe their future: they would sell their land and be treated as the children of the Great White Father in Washington. Or as children, anyway.

A member of that audience, Ohio doctor Henry Allen Smith, who had recently arrived over the Oregon Trail, jotted down what he thought he heard Seattle say. Allegedly fluent in the native Lushootseed language, what he actually understood was Chinook Jargon, a rough trade lingo of about 150 words that many whites thought was the native language. A native interpreter translated Seattle’s Duwamish dialect into the Jargon for a white translator who knew enough of it to put snatches into English for the governor. Smith’s notes might have come from the Jargon, but more likely came from the snatches.

Thirty-three years later, on October 9, 1887, he edited his notes and had “Early Reminiscences” printed in the Seattle Sunday Star, a short-lived journal for Sabbath reading, as the culminating tenth essay in a series celebrating pioneer life. “The son of the white chief says his father sends us greetings of friendship and good will,” Smith recorded Seattle saying toward the beginning of his speech. “This is kind, for we know he has little need of our friendship in return, because his people are many. They are like the grass that covers vast prairies, while my people are few, and they resemble the scattering trees of a storm-swept plain.” And then the speech disappeared.

But Seattle did not. Outside of town, others wrote about him. In 1868, a brief sketch in the Olympia Standard described his earlier days in Washington’s territorial capitol. In 1870, Charles Melville Scammon, whaler, naturalist and author, wrote a longer essay, “Old Seattle And His Tribe,” in Bret Harte’s Overland Monthly published in San Francisco. In 1886, he appeared in Portland’s West Shore magazine.

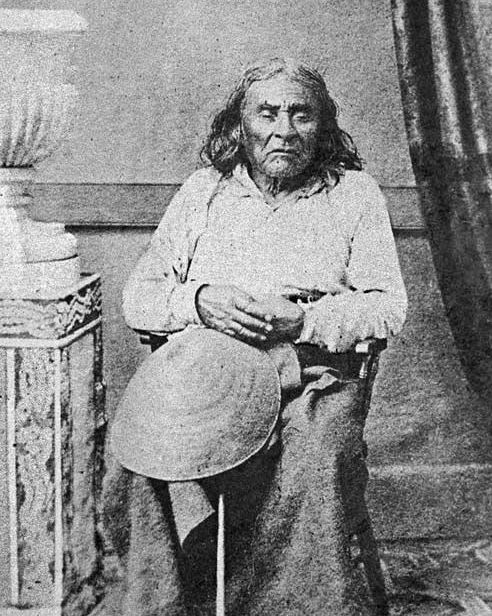

Across Puget Sound, Chief Seattle lay in a weedy Catholic mission cemetery beneath a shallow mound marked by a bare wooden cross. In 1890, to satisfy pressing curiosity, Seattle pioneers belatedly capped his grave with a marble cross (since vandalized), bearing the inscription: “Chief of the Suquampsh and Allied Tribes / DIED JUNE 7, 1866 / The firm friend of the whites, and for him the City of Seattle was named by its FOUNDERS. Baptismal Name NOAH SEALTH / AGE PROBABLY 80 YEARS.”

They gave their town his name, they later said, because it sounded nice. In truth, they could not pronounce it. It wasn’t Sealth, as whites originally conceived his name—there is no ‘th’ sound in Lushootseed. There is a glottal stop that we “hear” after the first syllable Si, and the second, AH, which is emphasized. This ends with a voiceless, lateral, alveolar fricative: the barred L, giving See-AH-lh. I believe the ending was the barred lambda, the voiceless, lateral fricative: “tl”, that settlers heard as ttle, giving See-AH-tluh—closer to "Seattle."

But as the city grew, the question remained: who was Seattle? An important clue was his estimated age: “probably 80 years,” placing his birth in the mid-1780s, when virgin-land epidemics, diseases for which Native people had no immunity, were introduced by maritime fur traders. Smallpox wiped out 50% of the population, and measles and typhoid killed many more. Societies crashed. Chaos increased with the introduction of firearms, mostly by American traders on the Northwest Coast and interior. Into this cataclysm, Seattle was born.

It is unnerving, 160 years after his death, to search out cryptic details and try to weave them into a plausible biographical garment for the man. Seattle’s life was marked by crises beginning with his birth. Was he a noble or a slave?

The lower White River, a stream that does not even exist today, drained what is now a dense industrial slurb between modern Seattle and Tacoma. On this river, he was said to have come either from the noble village of Stooq, or “log jam,” at the north end of a jam lodged during the turn of the 18th into the 19th century, or the low-class village, Ch-oo ta-PAHL tw, or “Flea’s House,” one mile upstream at the jam’s southern end.

The Stooq-AHBSH (AHBSH meaning, “people of”), hereafter the Log Jam people, appeared after the logs jammed and five noble families from the Black River, a conjoining stream, literally pulled up their house posts and rebuilt the longhouse at the jam’s lower end, enabling them to control traffic and lord it over their neighbors.

One of these, the Ch-oo ta-PAHL tw-AHBSH, the Flea’s House people (a myth told about their giant, lethal ancestors reduced by Elk Woman to mere fleas) may have once been noble, but became low-class, possibly because epidemics left many children orphans, thus poor marriage prospects, and they were treated like slaves by the Log Jam people. Some said Seattle’s mother was from Log Jam; others that both mother and father were cousins from Flea’s House: low-class on both counts. But his father’s name, Schwee-AHB, a family name on Hood Canal, suggests a noble lineage with inherited names. Seattle was an ancestral name inherited from the family of Shee-LAH tsah, Seattle’s mother. But, in 1854, a federal official hearing the native gossip that Seattle’s mother was a slave, wrote: “Tis a stigma, however, upon him, which, were it not for his known good sense, would take much influence from him”.

Given the ambiguity and attendant shame, it is not surprising that Seattle gained fame and wealth as a war leader. When raiders coming down White River threatened to attack villages on Elliott Bay, Seattle, around 20 at the time, approached a council that was discussing plans with one of his own. He proposed that and his young followers would ambush the raiders. It was a bold plan from a "son of a slave," but the council agreed to it.

Having grown up in the area, he and his men dropped a tree at a sharp river bend, positioning it only a few inches above the water. When the raiders arrived at night, they did not see it until too late; their canoes were upended, whereupon Seattle’s fighters came out of hiding and slaughtered the thrashing raiders with arrows, axes, and clubs. It was quick, bloody and successful, beginning a career that made Seattle a terror.

Becoming wealthy, he married and gathered slaves and concubines: women from poor families who sought connection with a wealthy man. Around 1825, he joined his uncle, k-TSAHP--Kitsap, a Suquamish war leader who had raised an alliance of Puget Sound groups victimized by attacks made by Cowichan slave raiders from Vancouver Island. Two hundred canoes would head north and attack the Cowichans in their own waters.

A story describes Seattle with the armada on a beach. Five canoes away, a Snohomish man taunted him, whereupon Seattle hopped over the canoes, picked up the man, and hopped back while the Snohomish swung daggers at him. Back on his side, unharmed, he threw the frightened man down—a demonstration of Homeric prowess.

He was said to be thickset and brawny, not tall and thin like his half-brother Su-QWAR-dle who later settlers called “Curly.” Seattle had a powerful voice. His guardian power was Thunder, and during winter dances, he shook rattles shaped like ducks and loudly sang his guardian’s song. The song matched a violent temper, and it was said that when he bellowed at a person in anger, that person shook.

Kitsap’s armada headed north, raiding villages on the way for supplies, and landed at a village on Vancouver Island which they sacked, enslaving its residents. The trussed chief told the allies that they were not Cowichans, but Cowichans would come by later that day on their way to attack the S’Klallam on the Olympic Peninsula. The allies laughed, loading prisoners as they prepared to head home, when around the point came great Cowichan war canoes filled with raiders.

Both sides were surprised, but striking up his war song, Kitsap slit a prisoner’s throat and the battle began. Cowichan canoes rammed the allies’ smaller craft, overwhelming them. Only a few craft escaped, carrying Seattle, Kitsap, and Kitsap’s brother TU-leh-bot, prostrate with an arrow in his eye.

A tactical disaster, it proved a strategic victory when the Cowichans, impressed by allied daring, agreed to a peace through intermarriage. It was an old practice: if a new and powerful group threatened, one could fight, but if the foes intermarried, the etiquette of family kinship mitigated violence and fostered cooperation.

Seattle later raided on the Snoqualmie River, the Olympic Peninsula, and back on the White River. But when not raiding, while travelling in his great Cowichan canoe powered by teams of paddlers, he boomed out to groups he encountered, ET-sah See-AHLH, “It is I, Seattle!” to quell their fear.

Around 1845, he carried out his greatest raid, leading S’Klallam, Suquamish, and his own Duwamish raiders against the Chemakum at the entrance of Admiralty Inlet. This once-powerful group, speaking a language that was different from their neighbors', now survived in a single village.

Surrounding it at night, Seattle and his allies attacked at dawn, slaughtering the Chemakum. But during the melee, a musket ball shattered the spine of Seattle’s son SAHQW-al, a warrior said to be as terrifying as his father. As his son crumpled, Seattle was heard to cry out, “Oh, my son! He is down!!” Nearing 60, it was time to change.

1845 was the year Americans settled at the head of Puget Sound, building a grist mill at the falls of the Des Chutes River, a place called Tum chuck, in the Jargon—“Strong water,” or Tumwater. They had visited the coast since the 1770s; Lewis and Clark wintered there in 1805-6, and later came the trappers, missionaries, and settlers. The settlers organized a provisional government whose militia fought the Cayuse and Palus Indians after the murder of missionaries on the Walla Walla River. Oregon became a U.S. Territory in 1848, but a Snoqualmie war leader, Put-KAH-deeb, Patkanim, held a great council on Whidbey Island that called for American settlers and British Hudson’s Bay Company traders at nearby Fort Nisqually to be driven out.

When Patkanim’s armed followers opened fire on the Fort in May 1848, and two Americans were killed, the newly appointed governor of Oregon Territory, Joseph Lane held a September show trial at nearby Steilacoom Barracks. Several of Patkanim’s brothers were tried for murder, convicted, and hanged the next day before a large Native crowd. If missionaries could not teach them to fear God, the governor wanted them to fear the Americans. Seattle was present.

Americans also bought Patkanim passage to San Francisco. Crowded with more than 20,000 people at the height of the gold rush, his visit had the desired effect. He said his heart had changed: there were simply too many Americans to fight.

Seattle came to the same conclusion on his own, but carried it further. With the Cowichan adventure in mind, he determined to bring Americans into his country and intermarry with his people so both races could prosper. That winter, he brought his Duwamish to Olympia, the territorial capitol of a new Washington Territory, where they built a beach village that Americans called “Chinook Street.” There, he selected promising figures to tour his homeland, exhorting them to settle among his people. They did.

He persuaded San Francisco businessman, Robert Fay, to start a fishing industry on Elliot Bay. By the summer of 1851, Seattle had 700 of his people working for Fay and the Swedish cooper George Martin, catching and barreling salmon for San Francisco and Hawaii. That fall, a pioneering group reaching Portland by wagon train from Illinois had sent David Denny and Charles Terry north to pasture stock. In Olympia, they met Fay, who brought them up to the bay where Seattle sent them on tour. Much impressed, David wrote back to his brother, Arthur, “There is room for 1000 settlers. Come at once.”

Twenty-six white men, women, and children arrived on a rain-swept morning on November 13, and soon, Seattle had his people help them erect cabins on the eastern shore. More followed, settling beside ancient villages. When famine threatened, Seattle’s Duwamish provided a canoe-load of potatoes.

When settlers needed to pasture stock, his cousin guided them to several nearby. When violence threatened, he put on an “entertainment,” reenacting the slaughter of the Chemakum to remind natives present in the audience who was in charge.

When Fay’s salmon rotted on the voyage out, he left, and Seattle returned to Olympia to find a replacement. This was Dr. David Maynard, a pioneer fleeing a bad marriage in Ohio who Seattle coaxed north by offering his granddaughter, Elizabeth, or “Betsy,” to share a cabin built by the Duwamish. In October 1852, Seattle also encouraged Henry Yesler, whose wife was back in Ohio, to stay and build a steam saw mill, offering the man his niece, Julia. Yesler stayed. The racially hybrid community took shape.

By then, settlers had already named it after their benefactor. Many young, single white men leaving California were eager to intermarry with Duwamish in Seattle. The settlement boomed.

It did so until Stevens began treaty councils, and Native people began to grasp what being treated as the Great White Father’s children really meant. Seattle had invited settlers to join his people in their homeland to prosper. The Americans wanted to remove the Duwamish from their homeland, because, with the discovery of coal and the approaching railroad, land had become too valuable to share. Other groups faced similar stark choices and chose to resist.

Seattle was the Duwamish chief. In the lead-up to the councils, the Suquamish asked him to represent them, and he became their chief. When the Suquamish received a reservation in their homeland west of Puget Sound, his authority was compromised. In the war that exploded throughout the territory, Duwamish up-river kin also fought the Americans, joining in the attack upon on the town in January 1856. Its survival hinged on Seattle’s and other Duwamish chiefs’ decision not to participate. Hostile up-river groups got a reservation; loyal Duwamish did not. Despite federal willingness to grant them a reservation near the town, local white residents fought the move successfully.

Being made landless had also made the Duwamish a federally unrecognized tribe, denied access to the promises guaranteed in the treaty they signed, by the Americans they invited in, nourished, and protected. This shameful injustice continues.

For the remainder of his life, Seattle strove to develop economic relations between the Duwamish and sympathetic settlers and businesspeople. But better-educated white professionals who moved in bearing racist baggage were less sympathetic. The Treaty of Point Elliott that the Duwamish signed was not ratified until 1861, giving the Duwamish one year before having to move to other reservations. Many remained at their old villages, providing labor, services, and expertise that whites valued. But when territorial legislators granted the town a charter, its new council passed an ordinance forbidding native houses within town boundaries. Seattle and his people had to go.

Most Duwamish remained in their homeland, acculturating to American society when necessary. And Henry Smith’s speech continued to intrigue Americans. Was it really what Seattle had said?

Yes and no. Smith presents Seattle mourning his dying people, warning Americans they may suffer the same fate: “We may be brothers after all.” But Seattle invited Americans to intermarry with his people so that both could prosper; why would he have mourned their death? He demands that his people be allowed access to the graves of their ancestors, then launches into a remarkable contrapuntal exercise describing the two races’ differences. But he makes a crucial point: while his people’s numbers may decline, the number of their dead in their long life in this world is vast.

Seattle spoke near winter solstice time when, in Native belief, the dead visited the living. This could be dangerous, especially if lonely ghosts kidnapped kindred souls. The Americans had left the graves of their ancestors, and where their dead went, none could say. When Americans died here, they would meet the Duwamish dead, and Seattle warned Stevens and the Americans that: “the dead are not powerless.” Indeed, he continued, the whites must “…be just and deal kindly with my people.”

Seattle’s message was far more than a ghost story. Everything he had done, by inviting Americans in, and in everything he strove to do, he envisioned a community in which both races could share not just life together, but a more abundant life. The trajectory of his life and speech, which Smith interpreted fatalistically as “we may be brothers after all,” is more like “we are brothers, after all.”

That was the message Seattle left with the governor and his American compatriots that cold day. Interest in it continues to grow; it has been rewritten and bowdlerized to an astonishing, even dismaying, degree. As a malleable symbol, Seattle has been molded to satisfy evolving notions of who we wish him to be: peacemaker, prophet, doomsayer, philosopher, even environmental saint. Although despised and traduced in his lifetime and used and misused by white Americans, his stature continues to grow. His Duwamish people, cheated, dispossessed, and ignored, continue to survive in a city that pointedly ignores or romanticizes them. Not a single mayor has sat down with them to discuss their and their chief’s claims upon our better natures.

One hundred and fifty-five years after his death, he is more relevant today than he was in his lifetime. His vision becomes more compelling as our society painfully confronts its contradictions. Let us continue to ask, then: who is Chief Seattle?