Bison are returning to tribal lands under a conservation program launched by Deb Haaland, the first Native American Secretary of the Interior.

-

Summer 2023

Volume68Issue4

The return of the American bison from near extinction is a conservation triumph. The iconic species, with its symbolic associations with frontier America, the Old West, and Native Americans, was down to a few hundred animals by the end of the 19th century. Today, there are about 30,000 (outside of the meat industry), many of them living large in national parks.

But the species, commonly known as buffalo, is still “near threatened,” according to wildlife watch groups; its numbers in the wild critically depleted, with fragmented herds and diminished genetic diversity. And they remain absent from the grasslands they once roamed, leaving many Indigenous communities struggling to reestablish their historical connection to these majestic animals, a deeply spiritual element of their heritage.

In March, Deb Haaland, the new Secretary of the Interior and the first Native American to serve in a Cabinet Secretary position in U.S. history, announced an innovative program to restore wild bison populations across their formerly vast terrain.

“The American bison is inextricably intertwined with indigenous culture, grassland ecology, and American history,” she explained at a Washington D.C. World Wildlife Day press conference. “Significant work remains to not only ensure that bison will remain a viable species, but also to restore grassland ecosystems, strengthen rural economies dependent on grassland health, and provide for the return of bison to tribally owned and ancestral lands.”

Tribal knowledge and stewardship will be integral to this restoration effort, she said.

Haaland is a 35th-generation New Mexican through her maternal lineage and a member of the Laguna Pueblo. As Secretary of the Interior, she supervises the Bureau of Indian Affairs and ten other bureaus responsible for the nation’s environment, water, wildlife, and national parks, along with managing 500 million acres of land.

Chosen for the position by President Joe Biden, she received Senate confirmation in early 2021. Previously, Haaland was one of the first Native American women to be elected to Congress (the other is Sharice Davids of Kansas). She quickly earned a reputation as a can-do lawmaker and was reelected in 2020.

Haaland’s mother was a Navy veteran, and her father, a Norwegian-American, was a Marine combat veteran who was awarded a Silver Star for his service in Vietnam. After moving around from one military post to the next, the family settled in Albuquerque. Haaland attended the University of New Mexico, and, while she was a struggling single mother, she supplemented her income by selling homemade salsa. She graduated with a degree in Indian law from the university’s School of Law.

In 2015, Haaland became the chair of New Mexico’s Democratic Party — the first Native American woman to lead a state party. “I got into politics because I really wanted more Native Americans to get out and vote,” she said in an interview.

With her bison- and prairie-restoration initiative, she is again breaking new ground for indigenous people. The federal government has committed $25 million to increase wild bison populations and relocate herds to tribal lands. “While the security of the species is a conservation success,” she said, “they remain functionally extinct to both grassland systems and the human cultures with which they co-evolved.”

Bison confer many benefits to their terrain. They turn the soil and aerate it with their sharp hooves, allowing it to hold more water; their manure provides fertilizer for plants; their wallowing creates small ponds, and their migratory roaming distributes seeds and facilitates prairie biodiversity. They are a keystone species, which means that hundreds of other species depend on their presence and their impact on the landscape.

Bison are the largest land mammals in North America, and the widest-ranging. Males are huge, weighing up to 2,000 pounds and standing six feet tall. They are startlingly agile and can jump high in the air and run as fast as a racehorse. Their distinctive hump is actually solid muscle that allows them to maneuver their heavy heads and the horns that protect them from predators. During freezing Midwest winters, they swing their horns from side to side to act as a snowplow so they can forage beneath the snowpack.

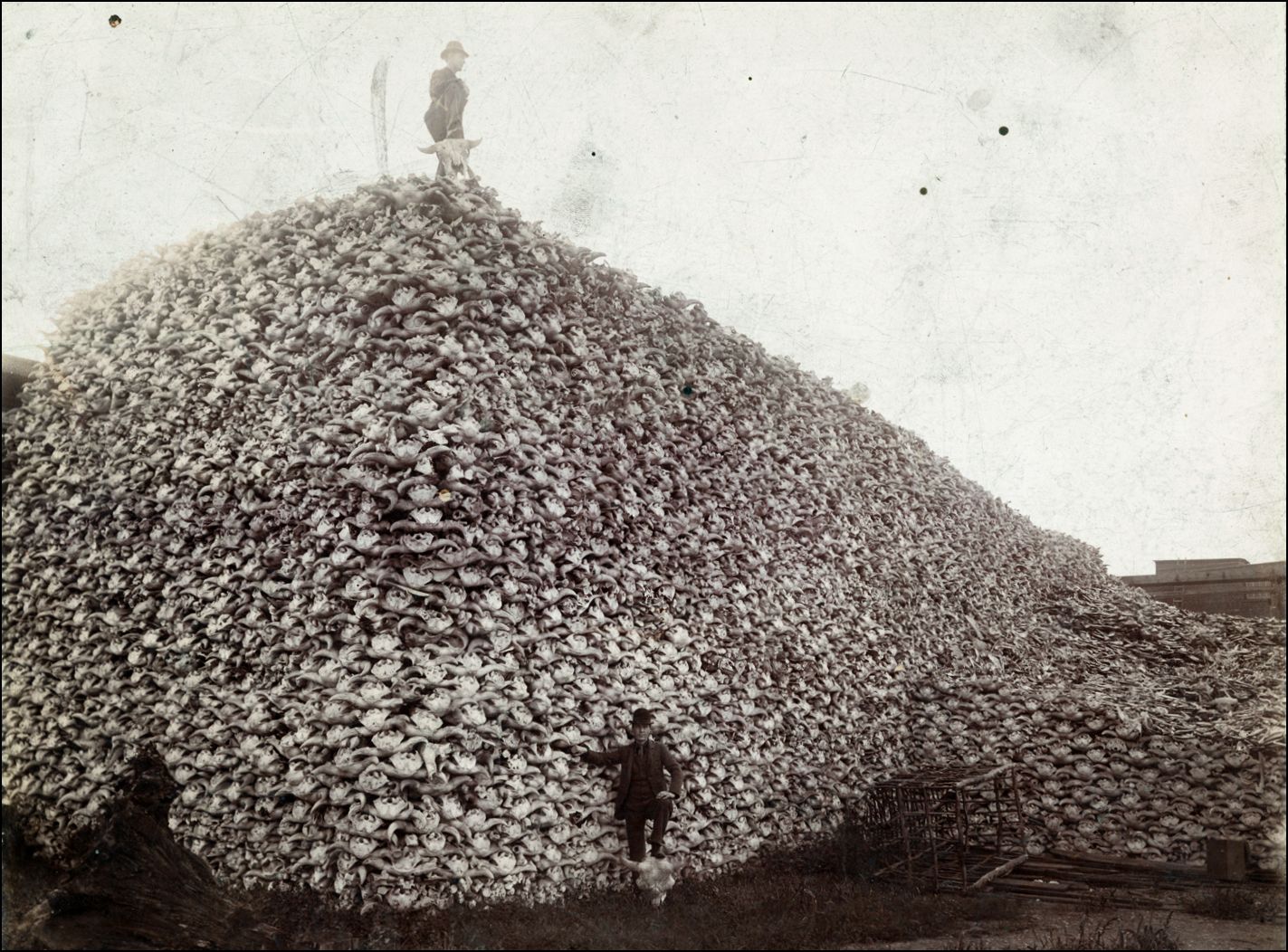

Bison once numbered upward of 50 million in North America, roaming freely for 10,000 years across the Great Plains and similar habitats from Canada to Mexico. Indigenous communities where bison were abundant developed a deep affinity for the species, and relied on them for food, shelter, clothing, tools, and cultural and religious rites. They used every part of the animal: sinews were used for sewing thread, and tails did duty as fly swatters. And these people were careful not to over-hunt their sacred Brother Buffalo.

During the19th century, wild bison were driven almost to extinction through wanton hunting practices and the Transcontinental Railroad that scarred the earth, brought increasing numbers of homesteaders farther west, and enabled mass wildlife slaughter by rifle.

In its wake came the devastation of western Native Americans; U.S. policy at the time was to allow the buffalo to be exterminated because doing so would subdue the Plains Indians who depended on them. Without their primary food source, it would be easier to force the tribes onto reservations.

The near-eradication of bison, combined with extensive farming, caused the almost total destruction of America’s prairie grassland. The result was vast acreage of soil without grass and sedge to hold it in place, and few trees to buffer the wind. When drought hit the Midwest in the 1930s, high winds blew the dry earth into enormous dust storms, turning the Great Plains into the Dust Bowl.

There had been public outcry about the mistreatment of Indians and the destruction of the bison before that, and private individuals, including ranchers and Native Americans, had protected some of the animals. But substantial conservation efforts weren’t enacted until President Theodore Roosevelt, a pioneering conservationist, put his political power behind the cause.

The largest number conserved was within Yellowstone National Park. Created in 1872, the nation’s first national park had a herd of wild buffalo within its borders. The small herd, descendants of bison that had roamed the area since the Ice Age, was almost wiped out by poachers, their numbers depleted to a couple of dozen. This galvanized state and federal agencies to pass laws to protect the species and to create wildlife refuges. The shaggy giants slowly rebounded. Today, the Interior Department manages 17,000 bison in herds on public lands in 12 states.

Still, the only truly wild bison now exist only in Yellowstone, which has about 5,000 of them. In January, the National Park Service completed the transfer of 112 Yellowstone bison to the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Poplar, Montana. It was the largest single bison transfer to date. Many other tribal communities will also receive wild bison.

Another of the goals of Haaland’s bison program is to facilitate bison hunting by tribes, and not just for tribal culture, but as a successful herd-management tool. For this to happen, the animals must be outside the park, which does not allow hunting. Yellowstone and the Interior Department are working toward arrangements to allow the larger herds to wander freely beyond its borders and to create new stomping grounds.

This would allow the tribes to have greater access to hunting—a more ecological (and humane) way of culling herd increases than shipping them to the slaughterhouse.

“This holistic effort will ensure that this powerful and sacred animal is reconnected to its natural habitat and the original stewards who know best how to care for it,” Deb Haaland said during the Wildlife Day ceremony in D.C. “When we think about indigenous communities, we must acknowledge that they have spent generations over many centuries observing the seasons, tracking wildlife-migration patterns, and fully comprehending our role in the delicate balance of this Earth.”