John Dickinson played a pivotal role in our Nation’s founding, from the Stamp Act to ratifying the Constitution, but his contributions are largely forgotten by history.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

Most of America’s leading Founding Fathers are familiar to Americans: George Washington is the “Father of Our Country.” James Madison is the “Father of the Constitution.” John Adams is the “Atlas of Independence,” while Thomas Jefferson is the “Father of the Declaration of Independence.” Benjamin Franklin, the “First American,” is the wise embodiment of American ingenuity. Alexander Hamilton is the plucky immigrant who established our economic system.

Although some of these men have become controversial in recent years, these are the “Big Six” whom most Americans know and revere. But there is a seventh. And he is perhaps the most important Founder for us now, in this politically polarized moment. His name is John Dickinson.

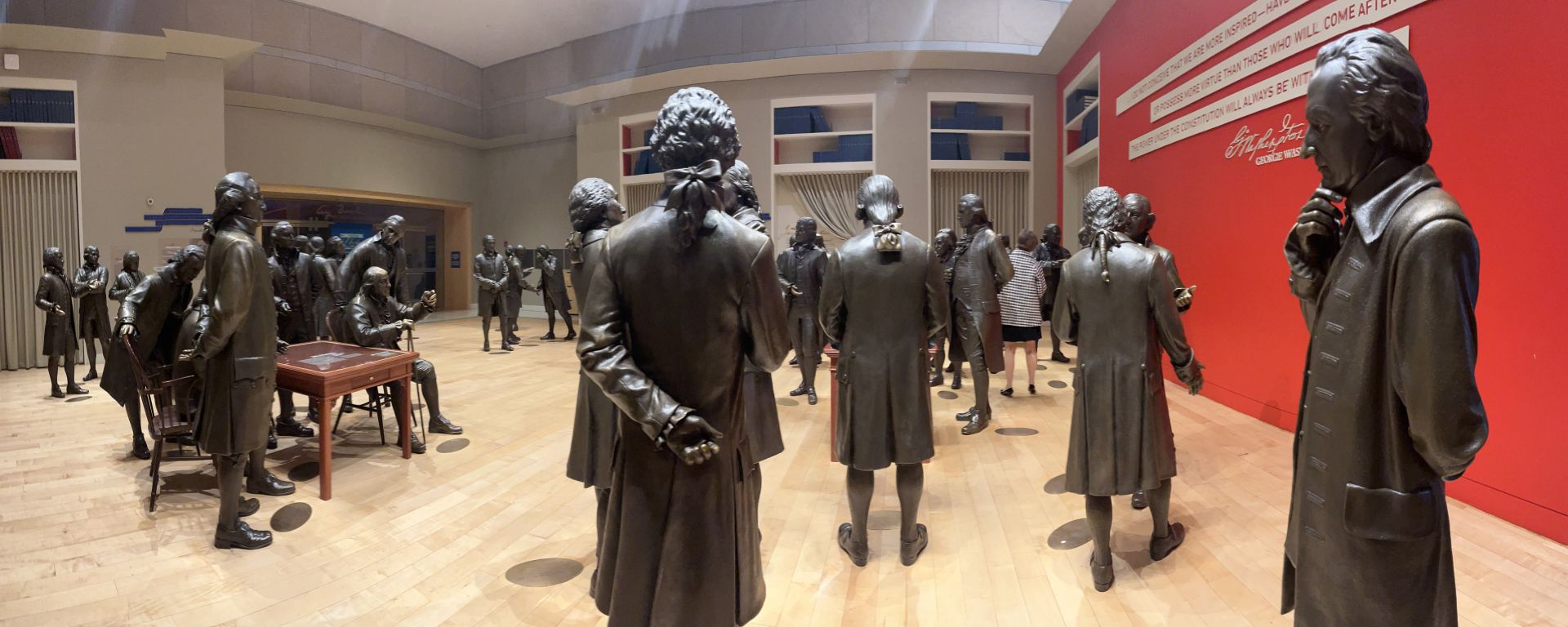

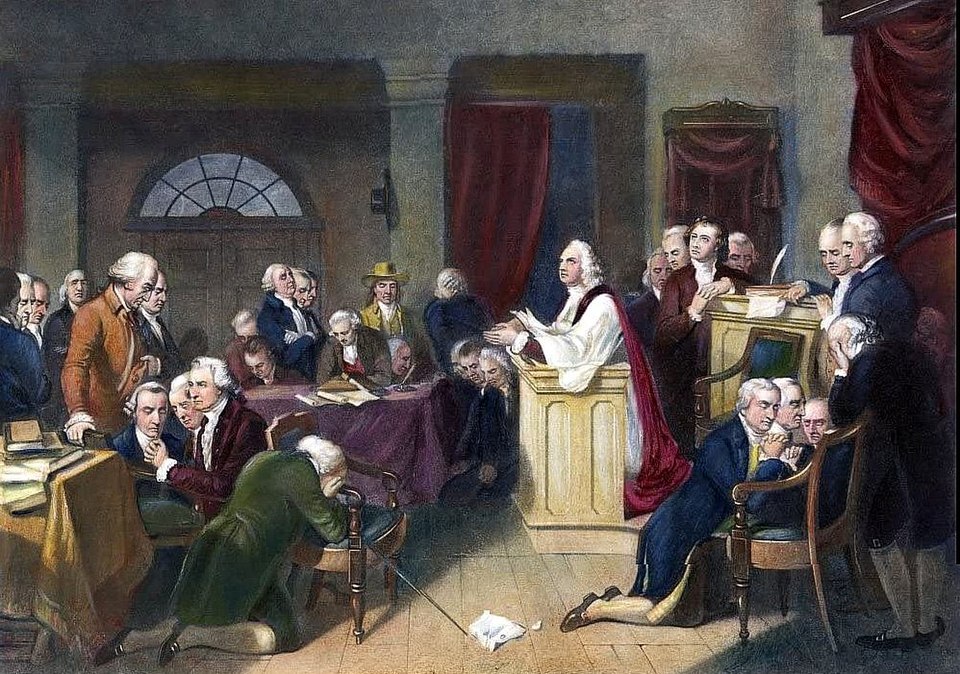

In Signers’ Hall at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, the statue of Dickinson stands alone in a corner, hand pensively on chin, apart from the action of the Federal Convention. The clear message is that he was too reserved, or perhaps too timid, to engage. He appears to be modeled on the Roman general Fabius, called “the delayer” for his caution in battle.

This is how Americans think of Dickinson—if they think of him. Alternatively, they might imagine him in the manner of the musical 1776, strutting across a stage, ever to the right, never to the left, with ruffles aflutter, singing jubilantly about his conservatism. There he at least possesses the virtue of energy. Or they could imagine him as HBO’s pale, sweaty, scowling disbeliever in the American cause, opposite a stalwart John Adams. But none of these images of him is accurate.

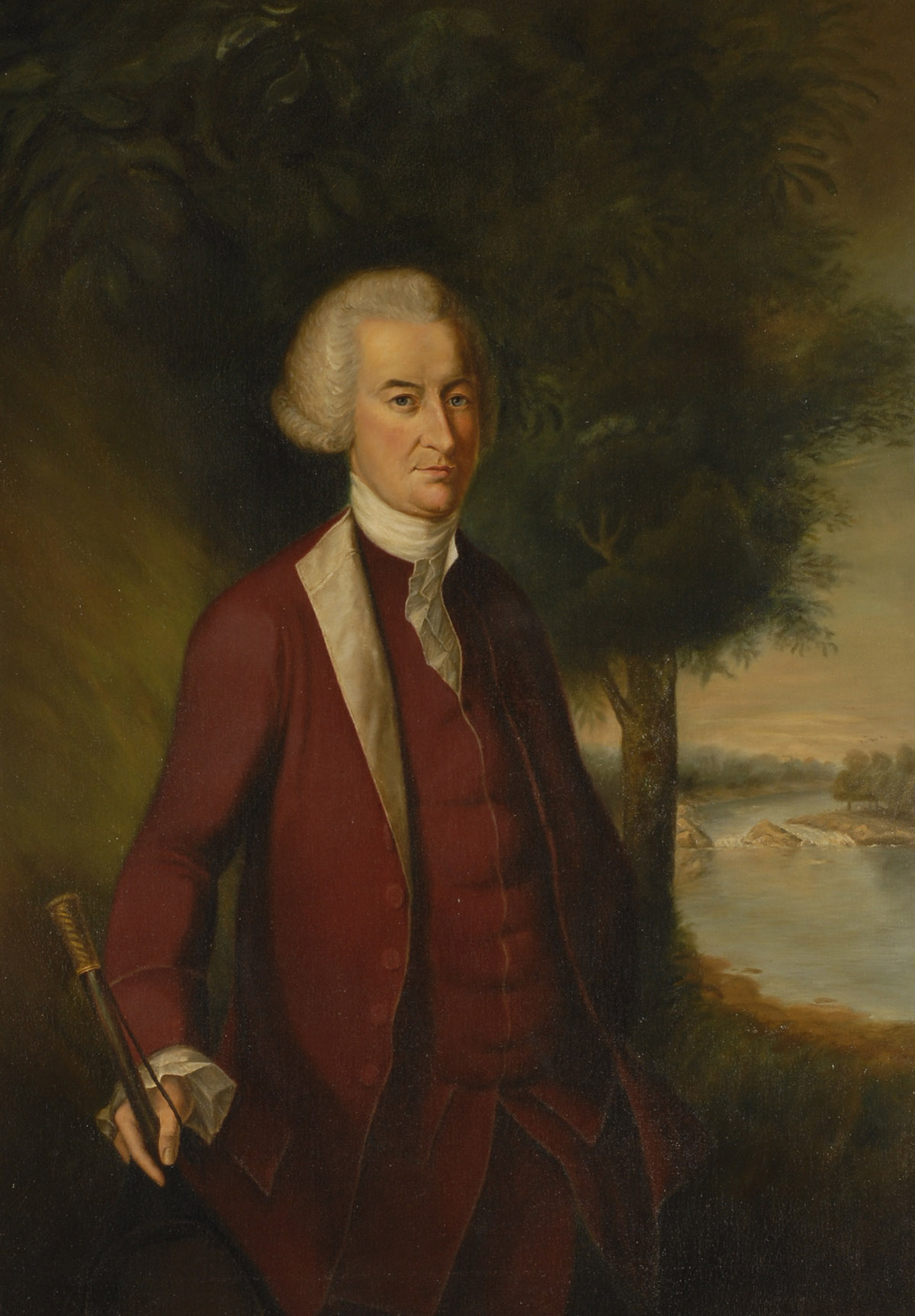

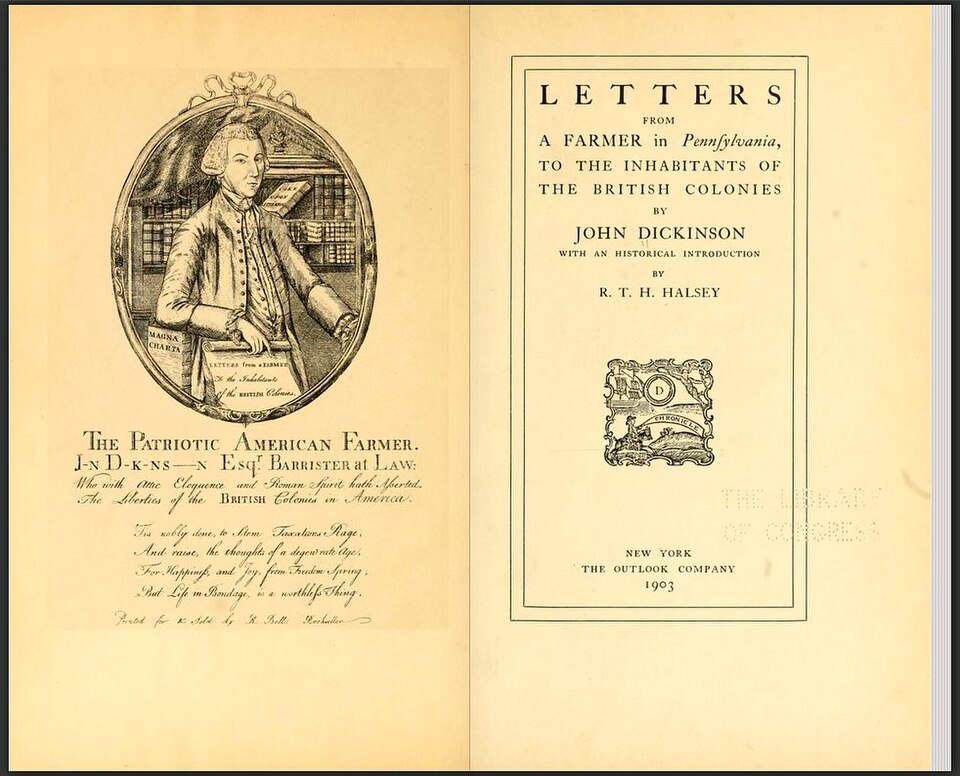

For more than two hundred years, John Dickinson has suffered from an image problem that no one in his day would have thought possible. Known for the better part of his life by his most popular pen name, the Pennsylvania Farmer, if there were a single individual who could be credited with bringing the United States of America into being, it would be Dickinson. Of course, such a claim for any one man would be absurd, but most Americans today, including many historians, would probably name Washington, Jefferson, or Franklin in that role without hesitation. Such a myth would be no more accurate than Dickinson’s withdrawn form at the Constitution Center.

In fact, Dickinson was America’s first celebrity and internationally recognized spokesman for the American resistance to Britain. The world knew and admired Dickinson’s name, or at least his pen name, well before they learned to idolize either Franklin or Washington. In his service in the national congresses and as a private citizen, he wrote more for the American cause than any other person, leading one scholar to designate him “the Penman of the Revolution.” But that, too, is a romantic misnomer, both too much and not enough.

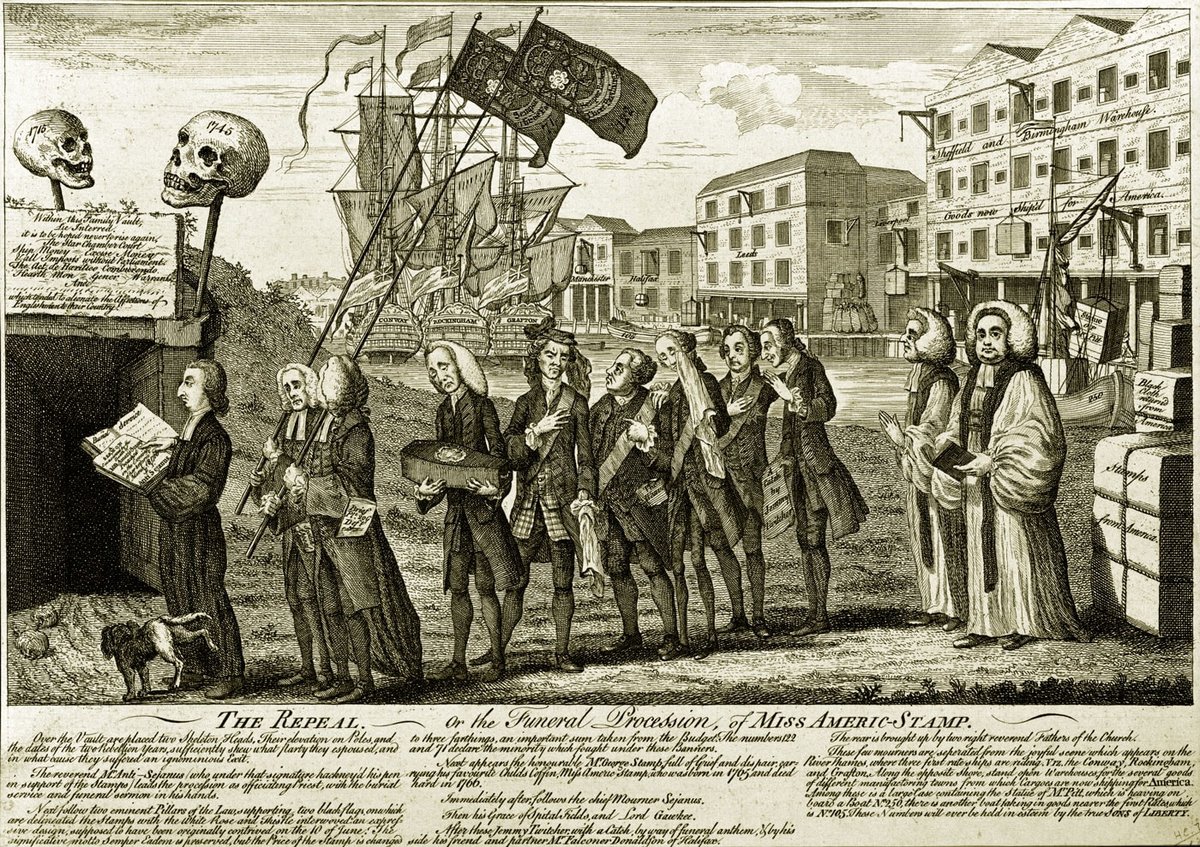

In the first instance, Dickinson didn’t want the Revolution and wrote against it. At this point, memories of grade-school history classes surface, and Dickinson’s present anonymity seems to make sense. Ah yes! He was the one who refused to sign the Declaration of Independence. True enough; he also refused to vote on it. Dickinson voluntarily and knowingly sacrificed his celebrity status, believing not only that he was doing what was best for his country but also that he would be compensated for whatever fame he lost during his lifetime by grateful posterity. While he was glad to be wrong about independence, he never regretted his decision, based as it was on conscience. Nor did he attempt to hide his decision or insert himself into a past event where he did not belong. He had no need.

This was because, in the second instance, he was much more than simply an author. The only leading Founder present and active in America at every phase of the Revolution, from the 1765 Stamp Act crisis through the ratification of the Constitution, he held more public offices than any other figure, from revolutionary committees to the presidencies of Delaware and Pennsylvania, for a while simultaneously. He had more extensive and varied military service than any leading Founder, not just raising and commanding a battalion as a colonel and drafting military policy, but also enlisting as a private and serving as commander in chief. At each stage, he produced documents that guided his countrymen in their efforts, paving the way to independence even as he sought to slow the movement and then working to secure the independence of the young republic.

In assuming these roles and as a private citizen, he, more than any other leading figure, attempted to put into practice the most famous principles of the Declaration of Independence as we interpret it today: that all people are created equal and deserve protection of their rights.

Dickinson’s contribution to the Founding of the country was exceptional. But a robust curriculum vitae does not tell us about the man, who he was, or what motivated him. One of the most highly educated men in America and, as one contemporary put it, “one of the most accomplished scholars that our country has produced,” Dickinson was a lover of literature and poetry, a devotee of science, and a voracious student of the law. He was driven by an unyielding sense of virtue and patriotism to work for the good of his country.

Born in 1732 to Quaker parents in Talbot County, Maryland, Dickinson was a devoted son. His father, Samuel, was a wealthy planter and a judge, and his mother, Mary Cadwalader, was highly educated, even reading law books by the fireside with her husband. When John was seven years old, the family, including his younger brother, Philemon, moved to Kent County, one of the three Lower Counties of Pennsylvania that now compose the State of Delaware.

From his erudite parents and tutors, Dickinson received the best education that could be had in the colonies, making him proficient in literature and poetry, history and political theory, the Classics and the Bible. At the age of 18, he began a legal apprenticeship with a former king’s attorney in Philadelphia. After passing the bar, he departed for three years of legal education at the Middle Temple, one of London’s Inns of Court. There he attained the status of barrister, the pinnacle of legal training in the British Empire, and he discovered his American patriotism.

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1757, Dickinson began a successful law practice, taking all manner of cases from the prosecution of small debts to lucrative causes in the Court of Admiralty, which handled maritime disputes and cases involving captured vessels. In 1759, he began serving in the legislature of the Lower Counties, and in 1762, he joined the Pennsylvania legislature, where he served intermittently through 1776.

Religion was always important in Dickinson’s life, growing in intensity as he aged. Although he was raised as a Quaker and was always closely associated with the Religious Society of Friends, as Quakers are properly known, he never formally joined the meeting (that is, the Quaker church). He shared most of their beliefs and concerns for social justice, such as women’s rights and abolitionism, but he was not a pacifist. For Quakers, religious liberty was a prerequisite to finding God in one’s conscience, which, they believed, rendered all persons, regardless of worldly status or physical attributes, equal in the eyes of God. Dickinson wholeheartedly shared this belief, which informed his behavior in all aspects of his life.

After he married Mary Norris, the daughter of one of the most prominent Quakers in Pennsylvania and a devout Friend herself, his Quakerism became more evident. Towards the end of his life, he dressed plainly and used the plain speech—“thee” and “thou” instead of “you” to signify human equality before God. Their two daughters, Sally and Maria, were raised Quaker, although only Sally formally joined the meeting.

Although Dickinson was one of the wealthiest men in America, he refused to follow the prescribed social norms of hierarchy or allow his privilege to excuse him from his duty to those less fortunate. On the contrary, his privilege dictated a greater obligation, and his Quakerly beliefs meant that he took on causes others avoided. He was a tireless champion for the underdog, be it a poor widow or a beleaguered colony. In his law practice, he frequently represented poor clients pro bono. As a statesman, he always donated his salary to charity. And as an author, he addressed the laboring people who hadn’t the luxuries of time and education to understand or follow legal and political developments. His were the politics of conscience, a civics lesson to future generations to stand on principle without regard for self or party. His thirty years of public service were a testament to his boundless faith in the American people, as were his attempts to educate ordinary Americans about their rights and draw them into the national dialogue on important matters of state.

His conviction that each individual was a “wheel” contributing to the public happiness contrasted with other thinkers of the age—Alexander Pope, Adam Smith, even Thomas Paine—who feared disruption to the mechanisms of government. Instead, Dickinson sought it and encouraged it in others. He alone among the leading Founders sought to protect the rights of subordinate populations—women, African Americans, the poor, criminals, and other disadvantaged groups. He was the only major figure to free all the Black people he enslaved during his lifetime and draft abolition legislation.

Dickinson himself chose the pen name “Fabius” to advocate ratification of the Constitution in a set of nine letters published in newspapers around the country. Directed to ordinary Americans, the “Fabius Letters” were more widely read than the best-known work today, the Federalist Papers. Also forgotten is Fabius’s genius, his innovative strategies, now considered the advent of guerrilla warfare, that allowed him to defeat Hannibal in the Second Punic War with minimal loss of life. He was respected by Hannibal and revered by the Romans, who knew he had saved their republic during the worst crisis in their history. Dickinson’s strategy throughout his career was Fabian. In every forum he entered—the courtroom, the state house, the battlefield—he was the chess master, controlling the unruly pieces, sometimes sacrificing the lesser for the greater—including himself for America—and never losing sight of victory: saving the republic.

Such encomia are not to suggest that Dickinson was without faults. His passion for education knew no bounds and caused him to transgress into didacticism as he played teacher to those around him. Although juries and law clerks undoubtedly found him helpful, his family and political opponents certainly did not. In his early years, his emotions could get the better of him. During one political controversy, he allowed himself to be provoked into a fist fight and even challenged his opponent to a duel. Perhaps from that embarrassment he learned to control himself rather too well. His studied circumspection in public office, though appreciated by some, enraged more forward spirits impatient for action. Some colleagues, such as those on the drafting committee for the 1776 Articles of Confederation, found him fussy about details as he edited and revised his work to an exasperating degree of perfection.

His inflexibility in matters of virtue, conscience, and patriotism, though admirable to an extent, may have been his Achilles heel, at times frustrating even his closest friends, earning him steadfast enemies in every phase of his life, and perhaps costing him his rightful legacy. His determination to take unpopular and highly visible stances made him a target like no other. But all the sources reveal that he came by his faults honestly in his attempts to do good.

In seeking to understand Dickinson and his legacy, the nautical metaphor of the “trimmer” is useful. The term can have negative or positive connotations in politics. It can refer to the person who trims the sails on a ship to go with the prevailing winds—the justly despised political opportunist. Or it can refer to the person who shifts the ballast in the hold to prevent the ship (of state) from capsizing or sailing off course by listing too far to the right or left. Dickinson was the latter type.

Here, something of an optical illusion occurs. While the trimmer stays true to the final destination—in this case, the preservation of American liberties—his shifting of the ballast appears to favor one side or the other. Moreover, because he is powerful, all parties desire his weight on their side. Assuming this role came at a price. As a seventeenth-century author described it, “the poor Trimmer hath all the Powder spent on him alone. . . . [T] here is no danger now to the state . . . but from the Beast called a Trimmer.” Though some of the powder was spent on Dickinson during his lifetime, much more has been used since. Dickinson accepted the former with grace; the latter, however, was unimaginable.

In 1785, the painter Robert Edge Pine wrote to Dickinson for permission to include the Pennsylvania Farmer in his painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Dickinson declined with an explanation. “The Truth is,” he reminded Pine, “that I opposed the making the Declaration of Independence at the Time when it was made. I cannot be guilty of so false an Ambition, as to seek for any Share in the Fame of that Council.”

This was just one moment, just one patriotic decision in a life devoted to public service. Dickinson was therefore sanguine about the one thing that haunted every Founder’s dreams: his legacy. “Enough it will be for Me,” he explained, “that my Name be remembered by Posterity, if it is acknowledged, that I cheerfully staked every thing dear to Me upon the Fate of my Country, & that no Measure however contrary to my Sentiments, no Treatment however unmerited, could, in the deepest Gloom of our Affairs, change that Determination.”

There is much more to Dickinson than that one moment. To distill his life down in such a way is to fail in our civic duty to understand our own history and give Dickinson the acknowledgment that he both expected and deserved. In a moment when Americans are deeply divided on politics, Dickinson’s example of patriotism and his message of unity are more important than ever.

In truth, he more than earned the nickname “Penman of the Founding.”