First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s evolving relationship with African Americans challenged her beliefs about herself and the world she had been raised in.

-

Summer 2021

Volume65Issue5

Editor’s Note: David Michaelis is the author of seven books, including the bestselling biography, N. C. Wyeth. Portions of this essay appeared in his recent monumental biography, Eleanor, the first one-volume biography in six decades of the longest-serving First Lady.

Eleanor Roosevelt always wanted things to happen faster.

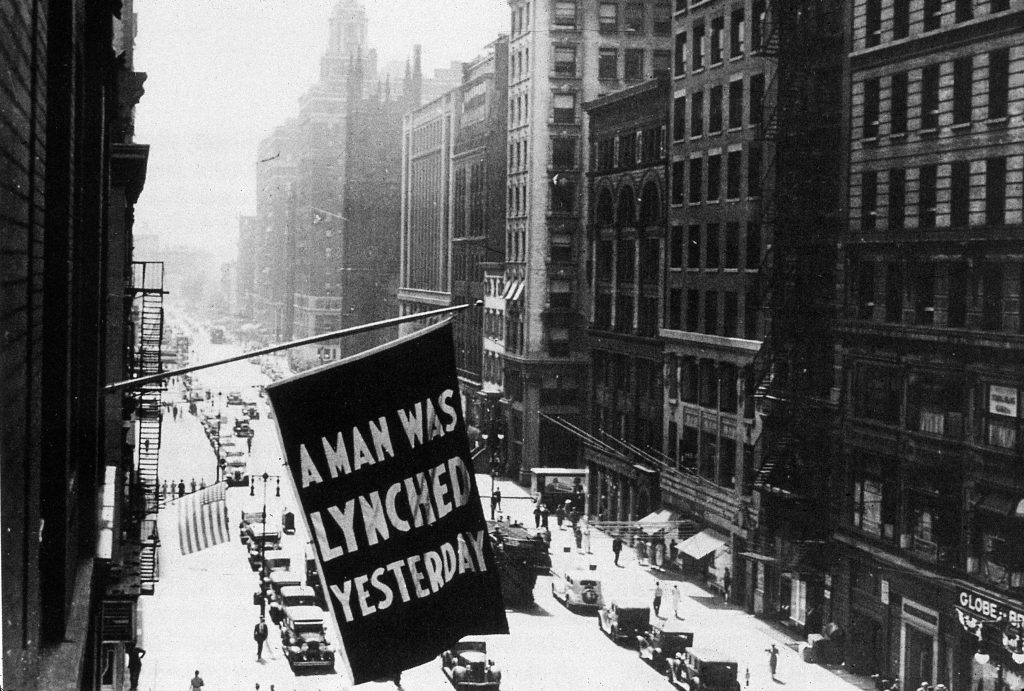

In 1934, her husband, President Franklin Roosevelt, wouldn’t take a stand on anti-lynching legislation. The Democratic Party, with many conservative Dixiecrats in positions of power, was ducking any issue that confronted African American segregation or injustice. So Eleanor felt it became her duty to respond, beginning with questions of discrimination in New Deal relief programs.

Eleanor had not recognized the depth of institutional racism during the New Deal until she became involved with the Subsistence Homesteads Division, an agency intended to help the unemployed return to farming. When she urged the agency to admit African Americans to Arthurdale, an experimental West Virginia community created a year before to provide opportunities for local miners and farmers, her intervention failed – as had every appeal she made to FDR to deal with the country’s terror crisis and champion anti-lynching legislation.

Joining the DC chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Eleanor made common cause with the national executive secretary, Walter White, the one determined crusader for racial justice in New Deal Washington. She now invited White, Clarence Pickett of the American Friends Service, and the presidents of six African American universities to the White House to discuss the Arthurdale situation.

At eight in the evening on Friday, January 26, 1934, Eleanor opened the problem of race in the homesteads to the group. One of the educators, Robert Russa Moton, a Virginia-born son of former slaves and the president of the Tuskegee Institute, had been the keynote speaker at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, where he had been kept apart from the other speakers and made to sit alone. Five years later, Moton, a lifelong advocate of accommodation in race relations, made a deal and supported Herbert Hoover, Coolidge’s secretary of commerce, then receiving highest praise for his handling of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which had cost more than half a million blacks their homes.

Hoover won the traditionally Republican black vote in 1928, but as soon as the Great Engineer had claimed his prize, he refused even to acknowledge Moton. Blacks turned on Hoover in 1932, and because Franklin had been the political beneficiary, Dr. Moton was now able to vent his frustration directly with the President, who came in from another meeting in the Oval Office and joined what became a historic and unprecedented tutorial on racial discrimination.

The meeting broke up after midnight, having “set before all of us,” wrote Clarence Pickett, “a new standard for understanding and cooperation in the field of race.”

The group had by no means solved the homestead issue, but FDR might have been pleased with Eleanor’s handling of it. After all, as Pickett recorded, “no one could have entered more fully into the nature of the problem or have expressed more intelligently a desire to find a way to help than did Mrs. Roosevelt.”

Over the course of her career, Eleanor Roosevelt’s wholehearted participation at interracial gatherings strengthened her position as an admired ally of African Americans, while her often-unexpected visits to black colleges, CCC camps, churches, and WPA housing projects drew praise from the leading voices of the black press.

“In our day, there has never been a mistress of the White House so energetic, so brave, and so fired with enthusiasm of service to the common people,” wrote an editor with the Baltimore Afro-American. All of this served to consolidate the President’s strength among black voters and panicking their Southern oppressors.

The idea that, “Negroes almost worshipped Eleanor Roosevelt,” as Black historian Rayford W. Logan told it, inflamed Southern politicians like Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge, who seized the opportunity to attack FDR through his wife, publishing photos several times through the campaign of Eleanor accompanied by African American ROTC students at Howard, captioned “N----r Lover Eleanor.”

Rumors circulated in many Southern states about “Eleanor Clubs” supposedly forming to activate African American female servants in white homes. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported that domestic workers were preparing to evacuate kitchens all across the state. In one version of the rumor, Eleanor herself had organized the members of the “clubs,” each of whom had sworn to resign on the spot if their white employers spoke against the President or his wife.

Many variations went the rounds: the Eleanor of Southern imagination had urged blacks to “show more backbone,” and therefore domestics had allegedly planned to engage in a sidewalk terror campaign to slam older whites into the gutter.

The club slogan was believed to be “All Negroes out of the kitchen by Christmas,” its members expecting to be received at the front door and addressed as “Miss” or “Mrs.” Reports from Texas, Mississippi, North Carolina, Alabama, and Florida prompted FDR to order investigations by the Secret Service and FBI, and though no evidence was ever found to support such claims, they were repeated so frequently that “Eleanor Clubs” became treated as fact.

Eleanor’s actual agenda accommodated segregation while championing equal opportunity. It was fine for the President’s wife to urge states to address the inequities in “separate but equal” public school funding — the farther from Washington and Dixie the better. FDR’s Virginia-born press secretary, Stephen Tyree Early, scarcely noticed the African American press extolling Eleanor’s sincerity and strength of character.

White supremacist Dixiecrats block anti-lynching bill.

By January 1934, she was receiving thousands of letters describing racial violence, poverty, and homelessness intensified by racial discrimination, all petitioning the President’s wife for help. Eleanor frequently forwarded the hardest cases to Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) administrator Harry Hopkins and his assistant Aubrey Williams, to whom she had already sent a list of suggestions of ways to include African Americans more fully within the organization’s programs.

Franklin was fine with that. White supremacists still dominated every committee of the House and Senate, but he was not concerned with them — some were good New Dealers, and he was candidly dependent on all of them as the firmest constituency of the Democratic Party.

Walter White had meanwhile been bombarding the President with telegrams, letters, and interview requests, all of which had been turned down. “I realize perfectly that he has an obsession on the lynching question,” wrote Eleanor to press secretary Stephen Early, “and I do not doubt that he had been a great nuisance. However, reading the papers in the last few weeks, does not give you the feeling that the filibuster on the lynching bill did any good to the situation and if I were colored, I think I should have about the same obsession that he has.”

The filibuster began on April 26. On May 7, Eleanor got FDR to agree to meet White to hear his side of the argument, in the hope that the President would intervene and break the filibuster. When Eleanor finally got in a word about the filibuster, the first thing the President did, defensively, was to explain to White his own predicament, giving one reason after another why he couldn’t support the bill. When White countered with detailed arguments, FDR lost patience: “Somebody’s been priming you,” he growled. “Was it my wife?”

“If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now,” continued the President, “they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass to keep America from collapsing. I just can’t take the risk.”

In October, Claude Neal, an African American farm worker in Florida, was arrested for the rape and murder of Lola Cannady, a white woman. He was abducted from the jail where he was being held, and the leaders of the lynch mob notified the press that justice would be served at the Cannady farm. Hundreds of people turned out to watch the lynching. Neal was taken to a secret location, brutally tortured, castrated, and killed.

His mutilated body was hung outside the county courthouse. Sheriffs buried Neal, but a large crowd gathered demanding to see the body, and a riot broke out. Nearly two hundred African Americans were attacked and injured during the riot. The National Guard was eventually brought in to control the mob. The lynching and subsequent riot attracted massive news coverage, and many Americans were outraged and disgusted.

In December, on a national radio hookup, FDR was finally moved to put the power of the presidency against lynching — but only because, when two victims were dragged out of the San Jose jail, they were white. Twice more, in 1937 and 1940, when the House passed anti-lynching laws, FDR offered no presidential sponsorship, remaining silent as the bills moved to certain death in the Senate.

Eleanor, alone in the gallery, stern and silent, sat in protest through hours of filibuster by the Southern wing of their party.

Thurgood Marshall, then a young lawyer arguing civil rights cases across the South for the NAACP, would later hold the President responsible for “most of the grim difficulty in changing racial patterns in America. He was not the great friend of Negroes that some people think. Now Eleanor Roosevelt did a lot; but her husband didn’t do a damn thing.”

Marshall would come uncomfortably close to this side of Roosevelt in 1941 when Attorney General Francis Biddle brought him onto a phone call with the President to discuss the NAACP’s involvement in a race case in Virginia. At Biddle’s instruction, Marshall picked up an extension phone, only to hear President Roosevelt thunder: “I warned you not to call me again about any of Eleanor’s niggers. Call me one more time and you are fired.”

“The president only said ‘nigger’ once,” recalled Marshall, “but once was enough for me.”

Eleanor’s regrettable gaff

As her second term began, people understood Eleanor as an urban liberal Democrat, foe of slumlords, friend of labor, advocate for the voiceless. She was trusted by the Washington African American community. Yet events of the next two years would force ER to challenge her beliefs about herself, the world she was leading, and the world she had been raised in.

On April 24, 1937, the Afro-American, a distinguished newspaper in Baltimore with distribution in other major cities, ran an editorial “with painful regret,” calling attention to “a serious error made by Mrs. Roosevelt in the May Ladies Home Journal when twice she uses the epithet ‘darkeys’ to designate members of the colored race. The error becomes grievously regrettable when one realizes the broad grasp that the First Lady has on public sentiment and the interpretation that is bound to come from her lack of thoughtful respect for a group that had come to believe in her with such profound admiration.”

The appalled editors of the African American press had every reason to take Mrs. Roosevelt at face value as not just a friend — but the friend — of racial equality. “What are we to believe?” George B. Murphy, Jr., managing editor, asked ER directly. “The fact that this reference appeared in print means that it was read several times after it was written, during revision and proof-reading. Will you please, then, tell us, as one of the small group of white Americans whom we have so far been able to respect and admire, how this harm came about, and what you, as an American gentlewoman, would care to do to correct it.”

Eleanor’s sharp-edged executive secretary, Malvina “Tommy” Thompson, not Eleanor, offered an explanation:

“In writing her autobiography, Mrs. Roosevelt was quoting her great aunt, who was born in Georgia and lived on a plantation, and who had great affection for the colored people. When Mrs. Roosevelt referred to them as darkies, it was a term of affection. She was talking of that period and quoting her great aunt, and the word had been used in all the early stories as they were told to Mrs. Roosevelt.”

But, in point of fact, ER used no quotation marks. She simply deployed the old language in her own autobiography, specifically to identify one person, namely, her father’s coachman.

Of course, no one mentioned the odd fact that the Roosevelts had been the original translators of their own tales from Roswell, the slave plantation where Eleanor’s grandmother, Martha “Mittie” Bulloch Roosevelt, was born. Well before Joel Chandler Harris popularized the Br’er Rabbit stories in the Uncle Remus books, Eleanor’s great-uncle, Robert Barnhill Roosevelt, had collaborated with her grandmother, taking the tales by dictation from Mittie, then confecting them for Harper’s magazine, where, as Theodore Roosevelt sternly noted, “they fell flat.”

Tommy concluded the explanation to Murphy with: “Mrs. Roosevelt had not the slightest intention of hurting anyone’s feelings and will change this word in the book, now that it has been brought to her attention.”

Still, the Afro-American insisted on an apology, which Eleanor delayed. When speaking or writing to white Southerners, Eleanor never hesitated to say that because of her Georgia ancestry she had “always had an understanding of the problems facing Southern white people on interracial questions.” She forthrightly stated that she “quite understood the Southern point of view” and was “familiar with the old plantation life.”

As for the African American point of view, “from my earliest childhood I had literary contacts with Negroes,” she explained to Ebony magazine readers in 1953, “but no personal contacts with them.” She recalled “reading about Negroes” when Aunt Gracie “would read to us from the Br’er Rabbit books and tell us about life on the plantation. This was my very first introduction to Negroes in any way. It was a rather happy way to meet the people with whom I was later to make many friends because all the stories our aunt told us were about delightful people.”

To a Tuskegee graduate who wrote her an outraged letter asking how “the paragon of American womanhood” could “use the hated and humiliating ‘darky,’” Eleanor did respond herself, explaining that it had been used by her Georgia great-aunt as a term of affection: “I have always considered it in that light. I am sorry if it hurt you. What do you prefer?”

Taking on Bull Connor

The Southern Conference for Human Welfare held its inaugural meeting on November 20, 1938, in Birmingham’s Municipal Auditorium. Labor’s new gains in organizing both blacks and whites in the cities and rural areas combined with bolder demands from African American churches to draw in labor leaders, industrialists, government officials, farmers and sharecroppers, civic leaders, ministers, politicians, economists, and students to create the largest liberal gathering the South had seen.

Out of the SCHW would come resolutions for federal legislation to abolish the poll tax; a movement supporting a federal antilynching law and “full citizenship for all persons regardless of race”; demands for equal pay for black and white teachers; a plan for a voting rights campaign, and more. The conference was billed as “the South’s answer” to the national emergency council report that “their section” was the nation’s foremost economic problem — a trope that Eleanor assailed from the moment she stood to address a mixed-race audience of more than seven thousand, including three thousand delegates.

On the second day, Eleanor spoke about the poll tax at an integrated workshop, then joined the full body of delegates at the Municipal Auditorium, which overnight had been surrounded with police wagons. Then, New Deal administrators, white and black leaders from thirteen Southern states, moved on into the building, deliberately violating the city ordinance that made integrated meetings illegal.

The stout, jug-eared rookie public safety commissioner of Birmingham gave the order in his bullfrog voice: “White and Negro are not to segregate together.” And with that malapropism, Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor nullified the agenda set by the President of the United States and made race the medium of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare.

Bull Connor pegged a cord from the lawn outside the auditorium and through its front doors, running up its central aisle to the stage, bisecting the seating so that at least two thousand African Americans ended up segregated from five thousand whites for Eleanor’s speech that evening.

Eleanor, meanwhile, had found a seat in the area set aside for blacks. Quickly, police marched up the center aisle to inform her she was in violation of the city statute. Rather than submit to the humiliating ordinance and take herself to the whites-only section, she deliberately placed her seat in the aisle. When she unfolded it and sat down, she was sitting squarely astride Bull Connor’s police line.

She refused to move, and Connor and his men dared not touch the first lady of the United States.

Likewise, Eleanor dared not make more of violating the ordinance. Asked by reporters, “What do you think of the segregation here tonight?” she answered, “I do not believe that is a question for me to answer. In the section of the country from which I come, it is a procedure that is not followed. But I would not presume to try to tell the people of Alabama what they should do.”

The Birmingham-raised historian Diane McWhorter observes that in context of the more personal firestorm of Bull Connor’s responses to the Civil Rights social revolution twenty-seven years later, Eleanor’s cool action in the Municipal Auditorium would be understood as “a gutsy moral stand.” But in November 1938, most white Southerners saw a low-level drama, “the wife of the president of the United States browbeaten by a crude radio personality,” starring their strongman Bull Connor in his national debut.

The next day, the conference voted to condemn the South’s Jim Crow laws and never to meet again in the future in cities with segregation ordinances.

Marian Anderson sings at the “first civil rights rally.”

The following year, the world-famous contralto Marian Anderson, sponsored by Howard University, was denied the chance to give an Easter Sunday concert in Constitution Hall, the only venue in Washington large enough for the diva’s usual audience. The powerful private organization that governed the facility — the Daughters of the American Revolution — cited their policy of limiting the use of the hall to white artists.

That was enough to set off alarms at Howard and in the press, which the DAR only magnified by defending its policy, touching a nerve throughout the capital city and beyond.

With Birmingham’s implacable defense of its segregation ordinances still at the front of her thoughts, Eleanor examined her own conscience as a member of the DAR, telling her readers, “I have been debating in my mind for some time a question which I have had to debate with myself once or twice before in my life. The question is, if you belong to an organization and disapprove of an action which is typical of a policy, should you resign or is it better to work for a changed point of view within the organization?”

In the past, when such an organization invited her to work actively, she usually stayed in until she had at least made a fight and had been defeated. Even then, upon accepting defeat, Eleanor invariably decided that she had been wrong to have let herself get that far ahead of the thinking of the majority. But to remain a member would imply approval of the DAR’s racist treatment of a great artist whom Eleanor had invited to sing at the White House three years before, and to whom Eleanor was now scheduled to present at the NAACP’s annual convention its highest honor, the Spingarn Medal.

And so, on February 27, Eleanor announced to her readers that she had resigned membership in a patriotic organization whose unjust actions she deplored. Privately she told the president of the DAR, whose name she had not revealed in her column: “You had an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way and it seems to me that your organization has failed.”

The first lady’s resignation — supported by 67 percent of Gallup’s respondents, 33 percent opposed — turned an episode of local bigotry involving a provincial ladies’ organization into an international news story that brought Eleanor further smears from Southern reactionaries alongside such awakenings of conscience from Northern whites as that which she received from old Dr. Peabody, still headmaster at Groton School, who shook his fist both at the DAR and at “the prejudice, I might say cruelty, with which we have dealt with the negro people. Your courage in taking this definite stand called for my admiration.”

Walter White collaborated with Anderson’s business manager, the famed entertainment impresario Sol Hurok, to propose that the diva present her program at an outdoor concert, free and open to all, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial — the “first civil rights rally,” as it would come to be called.

Legend to the contrary, Eleanor was not present to hear Anderson break the anticipatory hush of the audience with a proudly determined rendition of the national anthem, or the grave, supremely controlled “America” that followed. She had decided that it would be inflammatory for her to attend — her presence might incite haters. But she nonetheless opened up and magnified the day, having muscled those radio stations on which she herself broadcast to carry the concert live. Without those recordings, history itself might have been deaf to “freedom’s concert.”

Birmingham 1938 had pegged the boundary in Eleanor’s public life. After the Southern Conference she could not go back to the white world of official Washington and to business as usual. She now had to ask her readers why they swore vengeance upon Adolf Hitler but suppressed Marian Anderson. And she could no longer task Tommy to placate the editor of the Afro-American with some well-intended nonsense about how much Mrs. Roosevelt’s family had loved the servants it had enslaved.

In Birmingham, by defying the local statute and standing up and placing herself, as if for the first time, as the national intermediary, she had found her way to address the internal split running, as tautly as Bull Connor’s pegged cord, from the stage of the Municipal Auditorium, back up through the central aisle, out the main doors, all the way north to the big, now more inclusive spaces between Washington and Lincoln’s monuments.

For the rest of her life, Eleanor carried into the public sphere a whole new set of issues that had stubbornly remained outside ordinary discussion — the undiscovered poor, the unfortunate, the badly treated, the children of the world. As the first Chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights and later as Chair of John F. Kennedy’s Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, Eleanor profoundly affected the world around her and raised the question of how people of goodwill should respond to a whole range of matters — civil rights, racial justice and equality, working women. With her willingness to take the next step on racial injustice, and helped bring on the activism of the Civil Rights movement.