U.S. military leaders drew up elaborate plans to invade Japan, with estimates of American casualties ranging as high as two to four million, given the terrible losses at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

-

August 2023

Volume68Issue5

Editor’s Note: David Dean Barrett is a military historian specializing in World War II and is the author of 140 Days to Hiroshima: The Story of Japan’s Last Chance to Avert Armageddon, in which portions of this essay appeared.

On May 25, 1945, at the end of a long rectangular table at the Pentagon, sat General of the Army George C. Marshall and Admiral William D. Leahy. The two men had overseen all American armed forces during World War II. They were flanked by eight officers on each side. Also in attendance were Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King, Chief of the Army Air Forces General Henry (“Hap”) Arnold, and the members of the Joint Staff Planners. The meeting’s purpose was to finalize plans for the invasion of Japan.

Preparations had already begun in advance of the planned invasion. The Pentagon had moved to redeploy hundreds of thousands of men from Europe to the Pacific, on the assumption that the war with Germany would end no later than June 1, 1945. In the Summary of Redeployment Forecast dated March 15, 1945, the average number of men required was estimated at 40,000 per month, or a total of 720,000, just for army replacements from dead and evacuated wounded in the Pacific during the eighteen-month period associated with the redeployment.

General Marshall opened the discussion by reminding the group of President Truman’s commitment to impose unconditional surrender on Japan. He went on to state that such a surrender was a completely unknown concept to the Japanese, and that, to date, throughout the totality of the Pacific War, not a single organized “Jap” unit had surrendered to any American forces. As such, the Joint Staff Planners and General Marshall did not believe the continuing blockade and bombardment of the Japanese home islands would achieve that objective. An invasion, however, could be carried out to utter defeat, and the Army recommended it as the soundest strategy.

The Navy was not as convinced. Admiral Leahy argued: “Before we move on to the discussion of the invasion plans, I’d like to express my personal belief that we have not reached a point where this is the only or best option.” He remained concerned that the most recent experiences with the Japanese on Iwo Jima and Okinawa — slow, grinding assaults — were indicative of the kinds of losses the US could expect during an invasion of the biggest home islands of Kyushu and Honshu. While the Okinawa battle was not yet over, the American casualty rate on Iwo Jima was over 30%, and Okinawa appeared to be headed in the same direction.

Admiral King also voiced reservation, stating that kamikaze attacks had made American naval losses off Okinawa the worst of the war, exceeding even the 4,911 killed at sea during the Battle of Guadalcanal. In the event of an invasion of the home islands, kamikaze pilots would no longer need to fly more than three hundred miles to reach American ships. And troop- transport ships during an initial landing assault on Kyushu would be especially vulnerable to suicide-plane attacks. The Japanese were estimated to still have up to 2,500 aircraft, many of which could be used for the purpose.

Admiral Leahy noted that President Truman, who had taken over after the death of Franklin Roosevelt on April 12, was apprehensive about the potential casualties connected to an invasion. He thought that alternatives like strengthening the blockade against the Japanese mainland, and maybe the coast of China, coupled with the continuation of the strategic bombing campaign, could ultimately force Japan to surrender.

After Leahy finished speaking, Marshall asked if there were any other comments. As no one else spoke up, he shifted the group’s attention to the details of the planned invasion.

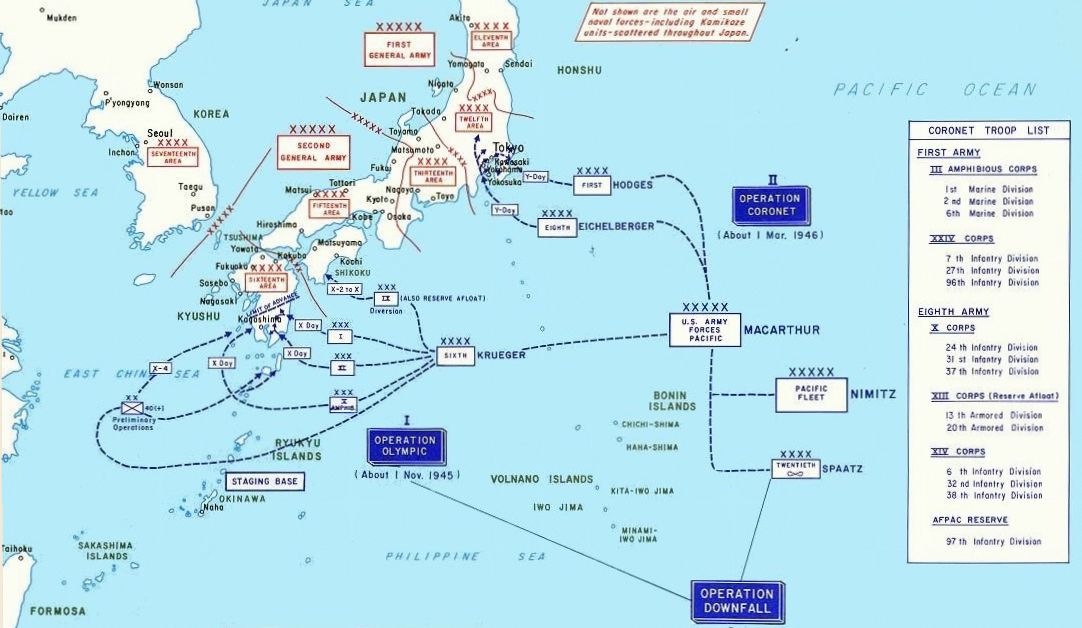

Code-named Downfall, the invasion would have two phases: Olympic, to be launched against the southern third of Kyushu on November 1, 1945, and Coronet, scheduled for March 1, 1946, with the slated objective being the capture of the Kanto (Tokyo-area) plain. For the first time in the war, all US resources in the Pacific would be devoted to a single objective. Admiral Chester Nimitz would have overall command of the naval forces, while General Douglas MacArthur would lead the ground troops once ashore. The invasion was planned to be much larger than the landing in Normandy a year and a half earlier.

A member of the Joint Staff Planners then took over the briefing. He explained that intelligence supported the plans for the invasion due to three factors: first, the Japanese fleet had been rendered incapable of more than a suicidal defense; second, Japan's material resources necessary to conduct war had been severely diminished; and third, potential reinforcements to Japan from Asia were being limited to an estimated one division per month. Further, the continuing destruction wrought by the strategic bombing campaign would, by December of 1945, have produced circumstances suitable for invasion.

The alternative strategy of a complete blockade and ongoing bombardment required twenty-eight divisions, only eight fewer than the thirty-six needed for Operations Olympic and Coronet, and that option would not be completed until the fall of 1946 — whereas the two-phase invasion strategy was expected to wrap up by the end of June of 1946. The planners were making the argument that, because blockade and bombardment would require just eight fewer divisions (approximately 120,000 to 160,000 fewer men, based on the size of divisions at the time) than both phases of Operation Downfall, and would not be fully implemented until the fall of 1946; even then, since that plan did not assure a definitive timeline to gain Japan’s capitulation, invasion was the best strategy.

But, while the planners hoped that Coronet could deliver a “knock-out blow” to Japan, they couldn’t say for sure that it would. Both the Joint Chiefs and MacArthur said that Allied military operations would continue until all organized resistance by the Imperial Army and Navy ended. In other words, no one knew if Coronet would actually end the fighting.

In preparation for the invasion option, the planners recommended the following courses of action:

- Apply full and unremitting pressure against Japan by strategic bombing and carrier raids to reduce its war-making capacity and to demoralize the population.

- Tighten the blockade by means of air and sea patrols, to include blocking passages between Korea and Kyushu and routes through the Yellow Sea.

- Conduct only such contributory operations as are essential to establish the conditions prerequisite to invasion.

- Invade at the earliest possible date, preferably no later than November 1 of this year.

- Occupy such areas in the industrial complex of Japan as are necessary to bring about unconditional surrender and establish absolute military control.

The military leadership had the following expectations regarding this campaign:

- The Japanese will continue the war to the utmost extent of its capabilities, and US troops will confront not only Japan’s armed forces, but also a fanatically hostile population.

- US forces will encounter three Japanese divisions in southern Kyushu and three in northern Kyushu.

- The Japanese will only be able to reinforce Kyushu to a total of no more than ten divisions.

- No more than 2,500 Japanese aircraft will operate against Olympic.

At that point, the Joint Staff Planners deferred back to General Marshall, who continued the briefing. He told the group that ground elements for Operation Olympic included both the Sixth Army and the Marine V Amphibious Corps. Their mission would be to seize and defend the southern third of Kyushu. The total projected commitment of forces was 767,700 men, 134,000 vehicles, and 1,470,930 tons of material.

Admiral King next described the naval forces that would be involved. The Third and Fifth Fleets would operate jointly for the first time to support the invasion. The Third Fleet under Admiral William F. (“Bull”) Halsey Jr., which had operated in the Central Pacific, including the Solomon Islands, Philippines and Taiwan, was assigned to give strategic support. The Fifth Fleet, which had fought in the Marianas, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, would directly conduct the amphibious operations.

Carriers would be the principal striking weapon. King indicated that the Navy, both American and British, planned to employ a total of thirty-two carriers with a combined air arm of 1,914 planes. Additionally, the Commander in Chief of Pacific Fleet Headquarters would be deploying 1,315 major amphibious vessels to back the ground forces.

At the conclusion of King’s remarks, Marshall brought up the issue of the “first use” of poisonous gas, something he believed needed to be discussed. Large-scale stockpiles of gas had been in the Pacific theater for some time, but US policy had always been that America would not be the first to use such weapons. Given the nature of the brutal, close-quarters fighting that had been so commonplace during the various island campaigns, Marshall wanted to take the temperature of the group to see if they’d recommend a change in policy.

“I’d like to raise an issue that we have prepared for, but, to date, have stayed away from,” he said, “and that is the use of gas against the Japs. I see gas as no more inhumane than phosphorous and the flame throwers, which we have already used and plan to make even more extensive use of in the battle to come.”

General Marshall was clear: He did not advocate the use of gas against dense populations or civilians — merely against the last pockets of resistance which had to be wiped out, but had no other military significance. He stated that “it might even be possible to saturate an area, possibly with mustard gas, and to just stand off, thus avoiding the attrition caused by such fanatical but hopeless defense methods of the suicidal Japanese.”

Hearing no support for the change in policy, Marshall switched back to the topic at hand — a vote on the invasion plans. He asked if there was an acceptance of the Downfall plan. It would be a decision of huge magnitude, and, while the navy clearly had expressed its reservations, they and their counterparts in the army all gave their approvals to Downfall and its objective — the unconditional surrender of Japan.

Despite mutual support for Operation Downfall, behind the scenes, disagreement over how to achieve unconditional surrender from Japan remained between the two services. The Navy, specifically, King and Nimitz, continued to favor blockade and bombardment. Both men assumed that the casualties from an invasion would be so massive as to erode American public support for unconditional surrender.

It was a belief hardened by decades of study of Japan, coupled with battlefield experience throughout the war, and driven home most recently in the ghastly battles for Iwo Jima and the ongoing battle for Okinawa, which ultimately resulted in over 230,000 deaths — warriors on both sides, and mostly civilians. In an invasion of Japan proper, naval planners believed that, despite America’s efforts to interdict the flow of Japanese defenders to the battlefield, inevitably, the enemy would outnumber any force the Americans could land, and the terrain, as it was on Okinawa, would counteract American advantages of firepower and mobility. On May 25, Admiral Nimitz informed his colleague Admiral King that he no longer supported an invasion.

In contrast to the Navy’s maximum effort to study a war with Japan, the army had done comparatively little. Marshall and the army preferred invasion because they were convinced it would produce a Japanese surrender far sooner than the blockade- and-bombardment option. Marshall also believed that, the longer the war went on, the more likely that American leadership would lose the public’s support for unconditional surrender.

His opinion on the need to end the war as quickly as possible was rooted in his experience as aide-de-camp to General John J. Pershing in World War I. As soon as Germany asked for an armistice in 1918, and before it had officially surrendered, Congress and the American public demanded a shift to demobilization. With Germany defeated, Marshall believed that, without a near-term victory over Japan, the mandate for partial demobilization could lead to a compromise settlement, one in which Japan could retain the core empire it still occupied in Taiwan, Manchuria, and Korea, and with no change to its political institutions.

That kind of end to the war in Asia would have fallen well short of the sweeping political and military changes that would come from unconditional surrender, and would leave Japan in a position to once again become a threat to peace.

On May 28, 1945, President Truman, who had served as an artillery captain in World War I, met with former President Herbert Hoover at the urging of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, who had also been Secretary of State under Hoover, to discuss, among other things, Hoover’s thoughts on ending the war with Japan. Hoover gave his estimates of the human costs if the United States invaded Japan, a subject of great interest to Truman, especially in light of the recent terrible losses of life on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Hoover offered a sobering assessment.

The source for Hoover’s estimates most likely came from the “smart colonels" at the Pentagon. Even though Hoover had been relegated to the “political wilderness” by his own party and the Roosevelt administration, he continued to provide frequent, low-key assistance to congressional committees.

Hoover told Truman that “there can be no American objectives that are worth the expenditure of 500,000 to 1,000,000 American lives.” That range of the expected number of men killed had to have shocked the president.

At the end of the meeting, Truman asked Hoover to recap his comments in a memorandum. Sent to the president on May 30, 1945, Hoover’s paper twice more reiterated his estimate regarding the American loss of life. It has to be emphasized that the numbers Hoover gave were for deaths, not total casualties, which would likely be in the neighborhood of four times the number of men killed in action — or two to four million total casualties.

Confronted with such astounding figures, in a few days, Truman sought further consultation. The day after the meeting with Hoover, Under Secretary of State Joseph Grew met with Stimson, Marshall, and Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal to discuss an end to the Pacific War. Was a peaceful solution possible? At the time, Grew was considered the most knowledgeable diplomat in the president’s administration on the subject of Japan, having spent nine years as the U.S. ambassador to the nation.

He told the group that he had met with President Truman the day before to discuss the topic and that the president was open to a peaceful conclusion to the horrible war, and he wanted to know their thoughts before proceeding. Grew had specifically proposed that the US modify its call for unconditional surrender to allow for the continuation of the Emperor Hirohito on the throne.

Henry Stimson was the first to respond: “On the surface, I don’t believe you’d get any disagreement from us on this point. There could be some real benefit in keeping the emperor, in gaining the compliance of the Japanese military to lay down their arms and cease hostilities. Conversely, if we don’t permit them to keep the emperor, the war may continue much longer and with ever-greater costs to us.”

George Marshall thought there could be benefits, as well, but he also believed that it was the wrong time to make such an overture. James Forrestal explained that “the Japanese militarists would likely seize upon any such initiative in the midst of our campaign on Okinawa as proof of crumbling American resolve.”

Henry Stimson then said that “the real feature that will govern the situation is the atomic bomb. Former Ambassador Grew was disappointed by the feedback to his proposal. He thanked the military men for their suggestions and said he’d pass them along to the president.

Stimson’s comment about the bomb was telling. Less than a week after the Joint Chiefs had approved the plans for Operation Downfall, the Secretary of War was already hoping that the invasion would not be necessary — that the atomic bomb could prove decisive. He and very likely all of his peers did not believe that the Japanese loss of Okinawa, the tightening blockade, and the ongoing and devastating bombardment of the Japanese homeland, or the knowledge of an imminent invasion, would cause Japan's leaders to surrender.

Only a real and successful invasion, or perhaps an unimaginable weapon, the atomic bomb, had the potential to do that.