Thousands of women marched in Washington and other cities, with female workers, floats, bands, and mounted brigades demanding the right to vote.

-

November/December 2025

Volume70Issue5

Editor's Note: Eleanor Clift

Excerpted from Founding Sisters and the Nineteenth Amendment (Turner Publishing, 2003[JS1][JS2])

When Woodrow Wilson arrived in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913, the afternoon before his inauguration, he was surprised to see the streets practically empty.

“Where are all the people?” he asked.

“Oh, everybody’s over on the avenue looking at the suffragettes,” he was told.

This was Alice Paul’s moment. On the eve of the inauguration, the radical young suffrage leader watched with pride as her handiwork unfolded. Eight thousand women took part in a procession that started at the Capitol, marched up Pennsylvania Avenue past the White House, and ended in a mass rally at the Hall of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Leading the phalanx was a dashingly beautiful young woman on a white horse, Inez Milholland . [JS4]She carried a banner of purple, white, and gold — purple for the royal glory of women, white for purity at home and in politics, gold for the crown of the victor.

Paul was a genius at public relations, and she pushed Milholland to the front of the parade, knowing that her exceptional beauty and ethereal presence, in contrast to the severe and stern image of the early generation of suffragists, would capture the imagination of the movement and the country.

Washington had never seen anything on the magnitude of this procession. Women from countries where suffrage had been granted walked first. Behind them came the “pioneers,” women who agitated for the vote as youths and were now well past middle age. Then came sections of marchers, one after the other, honoring the work of women in society.

There were nurses in uniform, women farmers and factory workers, homemakers and librarians, college women in academic gowns. Four mounted brigades, more than twenty floats, and nine bands added to the spectacular tableaux. Individual state delegations marched, followed by a separate section for male supporters of woman suffrage, and finally, in a shameful bow to southern segregationist sentiments, at the very back of the parade, a contingent of black women.

The New York Times called the event “one of the most impressively beautiful spectacles ever staged in this country.” But the pageantry was marred by violence. Paul had a parade permit that entitled the marchers to the streets, but the crowds of men who had gathered did not respect the women’s rights and surged onto Pennsylvania Avenue, heckling and jeering the women and making it almost impossible for the parade to pass.

The police stood by and did nothing as the women were tripped and shoved, spat at, and had lighted cigarette butts tossed at them. Washington still had a patronage police force, and apparently the officers didn’t feel the need to respond professionally even when some of the women were seriously assaulted. The newspapers noted that the police seemed to enjoy and even participated in the “indecent epithets” and “barnyard conversation” hurled at the women. The male marchers fared little better. They were ridiculed with shouts of “Henpecko” and “Where are your skirts?”

Among the marchers was the famed Helen Keller, who had overcome deafness and blindness to become a leading voice for women. The Chicago Tribune reported that Keller “was so exhausted and unnerved by the experience in attempting to reach a grandstand” that she was unable to speak later at Constitution Hall. According to the Tribune account, two ambulances “came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor to the injured.” A hundred marchers were taken to the hospital emergency room.

The situation deteriorated so badly that Secretary of War Henry Stimson, acting on a plea from the local chief of police, called in troops from nearby Fort Meyer to restrain the rowdy crowd. The violence made the front page of newspapers all over the country. “Mob Hurts 300 Suffragists at Capital Parade!” screamed the headline in the New York Evening Journal.

The marchers were mostly young women from respectable homes, and the spectacle of these fragile flowers of femininity, even if they were suffragists, being pushed and shoved by drunken men shouting obscenities proved too much for sedate Washington. There was a congressional investigation, and a Senate committee held several days of hearings during which more than 150 witnesses recounted what they had seen. It issued a blistering report on the failure of the police to protect the women, and the chief of police in the District of Columbia lost his job.

While Paul would never have condoned the violence, she had to have been secretly pleased. She had created the biggest splash around suffrage the country had seen. All anybody could talk about was the protest; the inauguration the next afternoon of a new president was anticlimactic. The burst of publicity came just when the suffrage movement needed an injection of adrenaline. “Capital Mobs Made Converts to Suffrage” declared the New York Tribune.

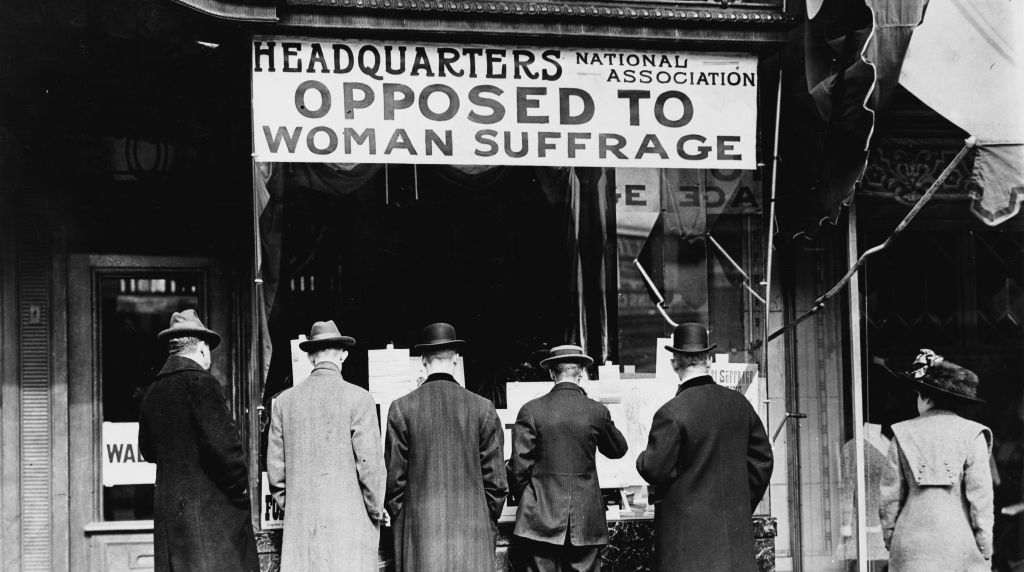

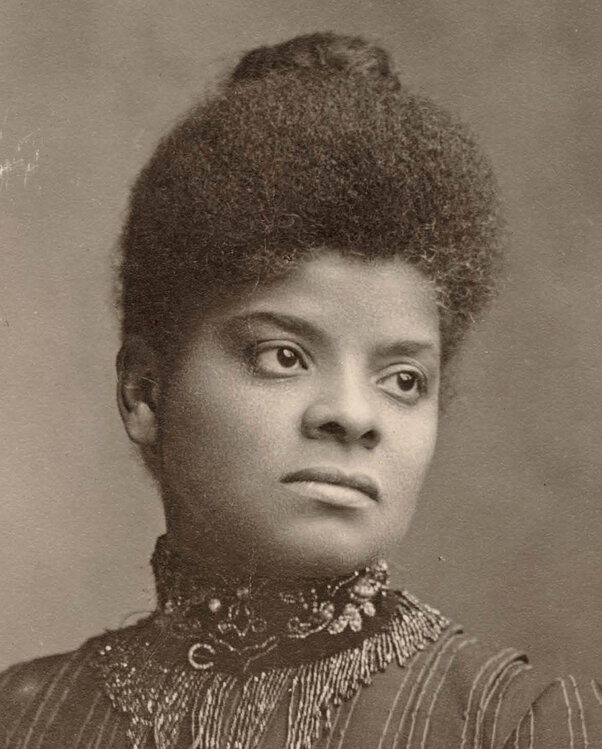

Paul’s hyperawareness of public images had an ugly side. Knowing she needed the support of white Southerners, she relegated black women to the back of the parade to keep them from marching alongside white women. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a journalist and antilynching crusader, was in Washington representing the all-black Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, which she had founded. A suffragist of long standing-she counted Susan B. Anthony as a personal friend—

she would not settle for second-class status because of race or gender. She waited on the sidewalk until the Illinois delegation came into view, quietly joining them for the march to the Capitol.

Paul was not the first suffragist to make calculated decisions about excluding blacks to placate whites. In 1894, when Anthony turned down a group of African American women who wanted to form their own chapter and join the NAWSA, it was her friend WellsBarnett who called her on it, though to no avail. Like Anthony, Paul was immovable once she had fastened on something. Opposition to suffrage in southern states was greater than in the North because of the fear that granting women the vote would increase the black vote exponentially and endanger the southern way of life, which depended on segregation of the races. With the votes of southern legislators in Congress and in the state houses essential if suffrage were ever to become a reality, Paul, and Anthony before her, made a pragmatic if unprincipled decision to keep black women at a distance.

As the suffrage struggle moved into its final chapter [JS5].Susan B. Anthony’s passing in 1906, the suffrage movement split between the moderates and the radicals.

The head moderate was Carrie Chapman Catt, who drew up what she called the “Winning Plan.” It focused on winning suffrage state by state, and putting in place the machinery to lobby lawmakers and influence voters. Her Organizing to Win pamphlet took women through the mundane process of creating a political operation, from naming precinct captains to distributing suffrage propaganda.

The head radical was Paul. A generation younger than Catt, she lived to create a stir, brimming with an impatience that sprang from her conviction that she had the answer. Slender [JS6]and frail-looking as a young woman with skin as pale as alabaster, she had extraordinary energy that seemed to emanate from the swirl of dark hair massed on her head.

Born a Quaker in 1885, Paul showed no early inclination toward feminism, but had an extraordinary degree of education for a woman of the time. She had a bachelor’s degree from Swarthmore and a master’s degree and a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. She also was a graduate of the New York School of Philanthropy.

A graduate student in 1907, she headed for England to study social work, where all the new social work theories were being developed. Working in the London slums, Paul happened upon a street-corner speech on women’s rights. She was captivated and soon became an acolyte of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst, a radicalized upper-middle-class woman named, who, with her two daughters acting as lieutenants, was at the forefront of Britain’s militant suffrage movement.

Pankhurst had turned to street protests after having her ideas dismissed at local council meetings. She was convinced that only the vote could confer respect.

There was nothing polite about the Pankhursts They thumbed their noses at the law, chalking sidewalks with notices of their meetings and parading through the streets with a hurdy-gurdy and a monkey. They encouraged their followers to crash government meetings and harass public officials, and when arrested, to went hunger strikes, all in the service of gaining publicity for their cause.

Alice Paul immediately fell in with the Pankhursts, and it wasn’t long before she was arrested and jailed for disrupting Parliament. Detained in the billiard room of a local police station, the only area large enough to hold more than a hundred protesters, Paul noticed a woman her age wearing a small American flag. Lucy Burns, a graduate of Vassar on a holiday break from her studies, had gotten swept up in the movement just like Paul.

The two women became fast friends and were twice arrested together, staging hunger strikes to attract attention and to provoke their jailers into releasing them early. But the prison authorities were on to the Pankhursts and their tactics. The next time Paul was arrested and sentenced along with another protester to thirty days in jail, refusing to eat did not win her freedom. Instead, the authorities forcibly fed the women, a painful procedure that involved inserting a tube down the throat and pouring in liquid food. The experience took its toll on Paul’s health, and she was pale and emaciated when she recovered enough to set sail for America in January 1910.

Paul arrived in time to attend her first convention of the NAWSA, which turned out to be an exercise in irrelevancy. Paul was only twenty-five years old, but what she had gone through stood in sharp contrast with the state of the movement in America and the concerns of her elders. The minutes from the convention are filled with page after page about whether some of the delegates had been rude and hissed when President William Howard Taft addressed them. It was the first time a president had welcomed the convention in all the years they had been meeting. While never acknowledging there had been hissing, the NAWSA sent the president a letter of apology, a bowing to authority that underscored the differences between Paul and the complacency she found when she returned home.

Even while the NAWSA clung to caution and decorum, progress was stirring elsewhere. Women in Washington state won a referendum in 1910 granting them suffrage, the first state victory in fourteen years, but with almost no help from the NAWSA.

The year 1910 turned out to be a watershed, with the win in Washington state paving the way for California in 1911, then Oregon, Arizona, and Kansas in 1912, all voting to give women the ballot.

Harriot Stanton Blatch, one of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughters, found the NAWSA’s conservatism so suffocating that she went off to found the New York-based Equality League of SelfSupporting Women. It was dedicated to ordinary women-factory workers and seamstresses-who had for so long been bypassed by the suffrage movement. Within a decade, the league had twenty thousand members.

Blatch changed the name of her organization to the Women’s Political Union, and staged the country’s first major suffrage parade, on the streets of New York City. The press coverage was brutal: marching was considered unladylike behavior, and even many suffragists braced for what they feared would be a backlash. But Blatch’s parade grew in numbers and status, and by May 1913 two months after Paul’s Washington, D.C., march— almost all the organizations in New York City clamored to take part, and an admiring media dubbed the event a “pageant.” That year, ten thousand marchers took part in the parade on Fifth Avenue, while hundreds of thousands of spectators lining the route cheered them on. One in twenty of the marchers was a man. In New York and California, men formed male suffrage leagues, which soon had chapters in twentyfive states.

When Paul had arrived in Washington in December 1912, eager to work for suffrage, she found that the NAWSA headquarters no longer existed and that most of the contacts she had been given were either dead or had moved away. The wife of a congressman, Mrs. William Kent, who chaired the NAWSA committee ostensibly charged with lobbying for suffrage, had a budget of $10 and no staff. Rather than get discouraged by the situation, Paul saw it as an opportunity. She befriended Mrs. Kent, an older woman who welcomed this eager young woman brimming with energy and ideas. The first thing Paul did was rent a basement office at 1420 F Street, between the Capitol and the White House, to serve as headquarters. A few weeks later, on January 2, 1913, in a small ceremony to inaugurate the space, Mrs. Kent introduced Paul as her successor.

Paul’s vision for a pageant to rival Wilson’s inauguration did not come cheaply. The senior officers of NAWSA told her to go ahead with her plans, but they would not provide any money. She was the upstart daughter arrived back from England with all these crazy ideas. She was a twenty-something kid who wanted to center suffrage activities in Washington while they were working methodically state by state.

Mrs. Kent and the other very-upperclass ladies drawn to the suffrage movement were unaccustomed to scrounging for money, and they did their best, selling trinkets at the F Street headquarters.

Paul, by contrast, had no compunctions about raising money. She pursued wealthy women with suffrage sympathies until they wrote a check. And she was creative. Bleachers had been set up along Pennsylvania Avenue for the inaugural parade, and Paul came up with the idea of selling tickets for the suffrage march. ’

The incoming administration looked the other way as hustlers parceled out the seats. Paul reportedly made a deal to get half the money collected to help pay for the 1913 suffrage march. The total cost of the event, from the twenty-page official program to the elaborate floats and costumes, was $14,906.08, a queen’s ransom in 1913, when the average annual wage was just $621.

Paul was often in the company of Lucy Burns, her constant companion and co-conspirator. The two women were opposites in appearance and temperament, just as Anthony and Stanton had been, as though another odd couple had been joined for the final push to suffrage. Whereas Paul appeared fragile, Burns was tall and curvaceous, the picture of vigorous health. She was warm and outgoing, full of Irish charm and with the blue eyes and red hair of her ancestry. Unlike Paul, who was uncompromising and hard to get along with, Burns was more pliable and willing to negotiate. Paul was the militant; Burns, the diplomat.

Abolitionists were the first to picket the White House, during the Civil War. But Paul’s parade was the first time anybody had dared disrupt a presidential inauguration. NAWSA leaders Catt and Shaw didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at the exploits of these two young women who had become their assistants. Worried always about whom they might offend, the older women tried to rein in the upstarts, who cared nothing about niceties. They had studied under Mrs. Pankhurst, and upsetting the decorum of Washington was exactly what they wanted to accomplish.

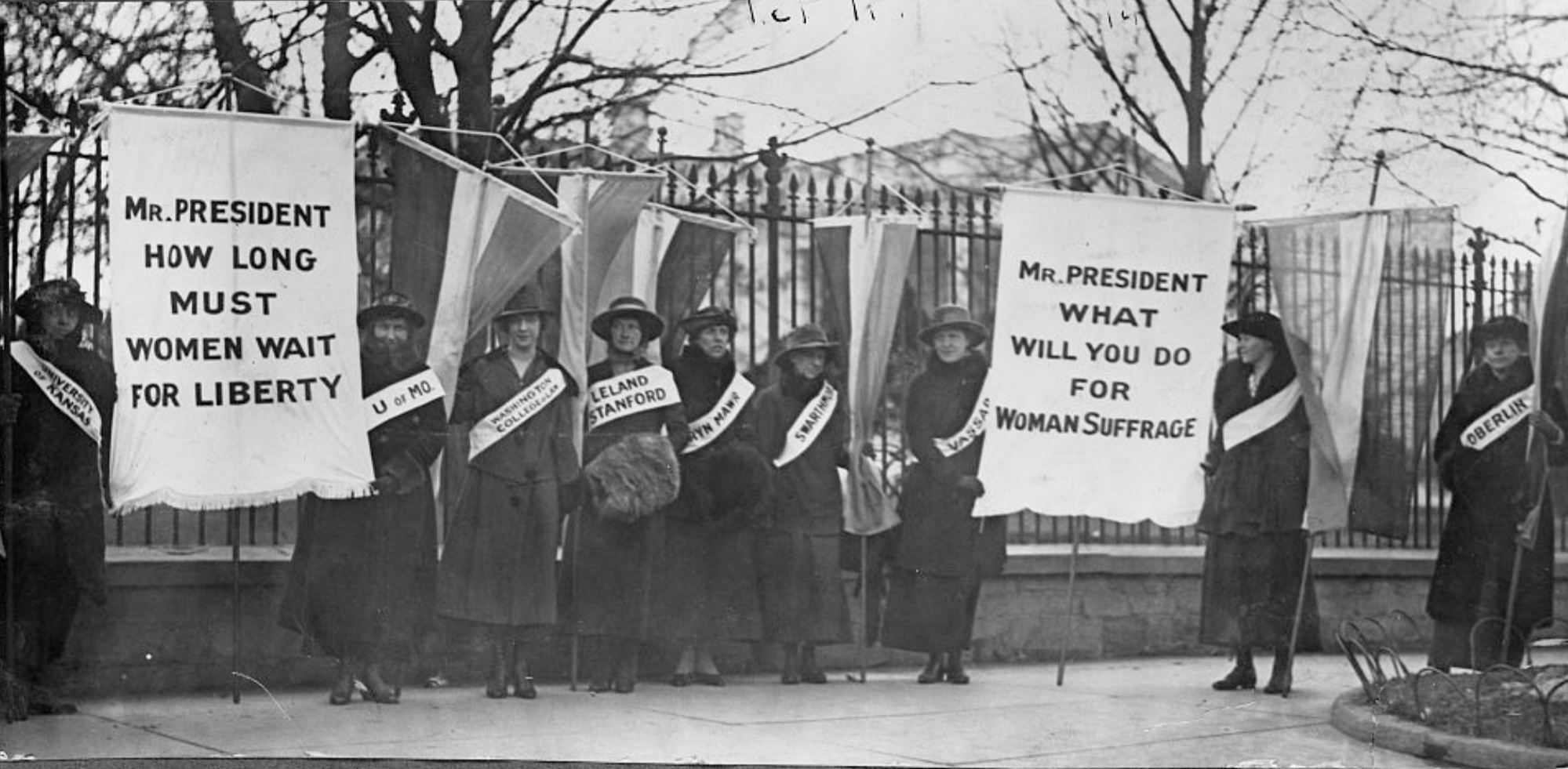

Following the parade, Paul organized a series of visits to the White House beginning on March 17, just days after the inauguration. Presidents were much more accessible then, and Paul wanted to press upon Wilson the importance of suffrage and the imperative that Congress act on the Susan B. Anthony amendment. Wilson received the women, but he played dumb about suffrage, saying he didn’t know enough about it and didn’t have a position of his own. Besides, Congress was too busy with currency and tariff questions to consider suffrage.

Paul concluded that Wilson would have to be educated, if not embarrassed, into seeing the light. The inside game was half the battle; there had to be pressure from the outside.

Relying on the techniques she had learned in Britain, Paul arranged a mass demonstration on April 7, the opening day of a special session of Congress, with suffrage delegates from each of the country’s congressional districts carrying petitions demanding passage of the amendment. They marched behind their state banners to the steps of Congress, where they were greeted by sympathetic lawmakers, who then introduced the amendment in both the Senate and the House exactly as it was written and first introduced in 1878. More petitions arrived over the summer in an automobile procession festooned with state flags that culminated at the Capitol and that forced a debate over suffrage in the Senate chamber, the first since 1887.

Emboldened by these events, Paul stepped up the pressure. A new Congress was scheduled to open on December 1; the tariff and currency questions had been resolved; now was the time to approach Wilson anew. But when the White House learned that a delegation of women from New Jersey, Wilson’s home state, wanted an appointment, Wilson was suddenly elusive. Paul didn’t like the runaround, so she informed White House functionaries that she and the others were on their way.

Marching in double file, seventy-three women rounded Pennsylvania Avenue and headed toward the White House. Miraculously, the uniformed guards saluted and made way for the women. Such was the power of protest – and publicity. This time Wilson was a bit frosty at being made to endure the impromptu visit. He still wasn’t ready to support suffrage, but he agreed to back the creation of the Committee on Suffrage in the House of Representatives — a small step to be sure, but a step.

The forty-fifth annual convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association opened in Washington’s Columbia Theatre in December 1913, and Lucy Burns unveiled the new strategy that she and Paul had devised. They would hold the party in power responsible. The Democrats controlled the White House and both houses of Congress; the Republicans couldn’t deliver suffrage even if they wanted to. It was an ultimatum to the Democrats: pass our bill, or we will defeat you for reelection.

Early in 1914, the tension between Paul and Catt over the direction of NAWSA came to a head, and Paul broke away from the mother organization. She had been functioning independently anyway as head of the congressional lobbying committee, raising her own money and staging her own protests.

When the NAWSA sought to collect a five percent tax on her funds as a condition of membership, Paul saw it as an attempt to cripple her activities. Together with a number of radicals and malcontents at the NAWSA, she formed the Congressional Union (CU). The CU was extremely active and attracted newcomers to the movement, something the NAWSA had been unable to do for years. The CU organized what today would be called “teach-ins” to educate women about suffrage, and sponsored parades, cross-country “pilgrim hikes,” and automobile processions to keep the issue in the public eye.

Despite those efforts, Election Day in November 1915 was a dark day. Suffrage lost in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania.

But the fight wasn’t over; it was just beginning. The suffragists never allowed the opposition to gain the upper hand for long.

Still, even the indomitable Catt could not conceal the depth of the defeat in losing three big-state ballot measures on the same day. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw resigned, yielding the presidency to Catt, who had been Anthony’s original choice for the job.

With Wilson’s daughter Margaret present as the honorary host at the NAWSA’s December convention in Washington, the delegates installed Catt as president and showered Shaw with roses as she stepped down after eleven years of service. Wriggling her head clear of the flowers, Shaw said to thunderous applause, “Men say we are too emotional to vote. But I am very sure that when we compare our emotions in political conventions with the kind they show in theirs, I prefer ours.” The New York Tribune reported Catt’s new watchwords: “Don’t Gossip ... Get Together ... and Work Hard.” The genteel proceedings struck Paul and her followers as hopelessly out-of-date, and their rift with Catt grew to Grand Canyon size.

Paul had already begun choreographing her next big spectacular, the largest-ever petition for suffrage carried across the country by “women automobilists” and presented to Wilson with great fanfare. It would convey 500,000 names and measure 18,333 feet. The convoys began going out during the summer of 1915, and in a country where cars were still a new phenomenon, the sight of these automobile processions winding their way through big cities and small towns, flying the suffrage colors of purple, white, and gold, attracted big crowds and lots of favorable press coverage.

The hundred-car procession arrived in Washington to the sound of the “Marseillaise,” the French national anthem and “Dixie,” stirring music designed to ally the women with anybody within earshot. From the Capitol, the marchers proceeded to the White House with the historic petition unrolled to its full length and borne by twenty women. Wilson received the women in the East Room, and while he had no intention yet of relenting to their demand that he actively press for suffrage, he seemed to be softening.

By October [JS7]1916, Inez Milholland Boissevain — who married Eugene Boissevain, a wealthy European from Holland, in 1913 — had spoken in Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Montana, Utah, Nevada, and California. Her trip was not been easy: a train at two in the morning to arrive at eight; then a train at midnight to arrive at five in the morning. “She would come away from audiences and droop as a flower,” Maud Younger, a women’s labor organizer who traveled with her, recalled.

At an October rally in Los Angeles, Boissevain cried out “Mr. President, how much longer must women wait for liberty?” With the word “liberty” still on her lips, she collapsed in a fain to the floor. There was speculation that she had leukemia, or some terrible fever, or that she had simply given out because of the strain. Whatever the reason, she was dead ten weeks later, a martyr for the cause. She was thirty years old.

This was no fragile flower who wilted when the train travel took its toll. For all her delicate beauty, Boissevain had beena seasoned radical and determined suffragist. On her first college vacation as a student at Vassar, she traveled to London where, like Paul, she became enamored of the Pankhursts and once was arrested. After graduating from Vassar, Milholland applied to Harvard but was denied admission because she was a woman. The rejection only spurred her activism, and she joined the shirtwaistmakers’ strike in New York, where she was arrested and held for several weeks before the charge against her of leading an unlawful assembly was dropped.

Her merger with Boissevain further ensured that she could continue her suffrage activities uninterrupted by financial concerns. She traveled at will, and accumulated a worldwide reputation as a suffragist and pacifist.

With Paul’s eye for pageantry, she arranged a glorious send-off for Boissevain following her death. Predictably, Paul did not take no for an answer and proceeded with plans for a memorial service. So great was Paul’s powers of persuasion that as the appointed hour approached, one by one, the obstacles posed by the authorities melted away, and the Capitol police could be seen helping to place the trademark purple, white, and gold suffrage pennants around the chamber.

The memorial service was held on Christmas Day 1916, and the vibrant greens of the season served as the backdrop to the suffrage colors. As the guests took their seats, an organ played “Ave Maria,” and a boys choir paraded slowly into the hall. They were followed by a suffragist caring a duplicate of the banner Inez Milholland had held a loft in the first suffrage parade in New York in 1912, and then a procession of younger women dressed in purple, then white, then gold, each division bearing a golden suffrage banner. The sweet voices of the young boys filled the chamber, followed by speeches of tribute.

Maud Younger summoned up a poetic remembrance of her compatriot, “a falling star in the western heavens” and urged that Boissevain’s sacrifice inspire the cause of suffrage: “that dying she shall bring to pass that which, living, she could not achieve, full freedom for women, full democracy for the nation…”

The organ sounded triumphant chords of the “Marseillaise.” The battle was once again engaged.

The suffrage struggle continued until August 1920, when Tennessee became the final state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

See also “Women’s History,” by Jean Baker

Because the woman suffrage movement was of such long duration, because it went through so many iterations, categorical claims about what suffragism was — and wasn’t — are suspect. The claim that suffragism was a “single issue” movement, that as its advocates determined to win political equality for women, they ignored other claims for social justice. This characterization may have been true of the suffrage militancy of the final decade — the picketers and jailed hunger strikers whose heroic actions have lodged in historical memory as the essence of suffrage activism. But even in the 1910s, this insular suffragism was more characteristic of a few leaders than it was many of their followers, suffragists who were also dedicated peace activists, birth control advocates, and trade unionists.

Nor was it true that the woman suffrage movement was voiced exclusively by and in the name of white women, and that deep-seated racism was its fatal flaw. For much of its history, the demands for woman suffrage and black suffrage were bound together, but that statement must be carefully parsed. Women’s right to the vote would not have been demanded and not have entered into the political discourse in the first place if its initial leaders had not been deeply involved with the abolitionist and black suffrage movements.

The suffrage movement and African American women

But in the post-Reconstruction years, this bond was broken as the mainstream woman suffrage movement excluded black women. This development was of a piece with the larger social and political reaction to Reconstruction. The grand conclusion of the suffrage movement was tainted by the ironic fate of its coinciding with the very nadir of post-slavery racial politics.

Still, it must be said that every other white-dominated popular political movement of that era similarly accommodated to insurgent white supremacy. And yet only the woman suffrage movement — not the Gilded Age labor movement or the People’s Party or even Progressivism itself — has been so fiercely criticized for the fatal flaw of racism. Historical memory recognizes the cautious gains of other reform movements of that era, even as they, like woman suffrage, turned away from the rights of black people.

Throughout the entire seventy-five years of the woman suffrage movement, and continuing into the post-suffrage era, African American women remained stalwart defenders of women’s political rights, with their numbers growing over time. Some of these women were well-known national figures — Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell — but most were not. There were numerous less-known activists who were part of the larger current of suffrage history. They understood what W. E. B. Du Bois preached in the pages of The Crisis in 1912: “Every argument for woman suffrage is an argument for negro suffrage. Both are great movements in democracy.”

The suffrage movement is reinvigorated

By 1912, six states had given women the right to vote, starting with Wyoming in 1890 and including Colorado, Washington, and California. That year, three more states would join them. But state by state enfranchisement was not enough. An amendment to the federal constitution was necessary. Every January, when a handful of suffragists would dutifully go to Washington to testify on behalf of a woman suffrage constitutional amendment before a tiny group of legislators, the process had become a meaningless ritual.

Finally, in 1912, the excitement, youth, and optimism of twentieth-century suffragism came from the enfranchised states to the national movement in the person of Alice Paul. Born in 1885 to a wealthy New Jersey Quaker family, she was exceptionally well educated, first at Swarthmore College, and later earning a PhD in political science from the University of Pennsylvania. In 1907, she went to London, where she served an apprenticeship to Emmeline Pankhurst and learned the ways of what had become known as the British suffragettes.

Paul had experienced all of this — including arrests, a brutal imprisonment, and a gruesome month-long hunger strike — by the time she returned to the United States in early 1910. She was celebrated by journalists as America’s first genuine suffragette. She was just twenty-six years old. Two years later, with the help of Jane Addams and Harriot Stanton Blatch, Paul’s proposal to revive the campaign for a federal amendment by the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was accepted by the group’s executive board. The young ambitious woman took over the association’s nearly defunct congressional committee and assembled a small group to join with her to reinvigorate the constitutional amendment campaign.

Paul had learned from the British suffragettes to deploy public demonstrations for maximum popular attention and to hold the political party that was in power responsible for inaction on women’s enfranchisement. To do both, she determined to begin her constitutional amendment campaign with an unforgettable demonstration in the nation’s capital that would be directed at the incoming Democratic administration. Paul scheduled her event for March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of newly elected President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson’s coattails had carried a Democratic majority into Congress, and this made him exceptionally powerful. The parade was designed to demonstrate the suffragists’ numbers, organization, and determination. When Wilson stepped off the train from his home in New Jersey for his inaugural ceremonies, he asked why there were no crowds to meet him. They were all on Pennsylvania Avenue he was told, watching the suffrage parade. Or so the legend goes.

Paul had a way about her, a unique kind of charisma that had already convinced veteran leaders to trust her with major responsibility. She did not advance herself personally at all. She was neither particularly warm nor intimate. Her considerable authority came from her absolute clarity about her intentions and her faith that other women could do whatever was necessary, even when they themselves had no such conviction. Working with her made them into more than they ever thought they could be. It was as if a whole generation of young women were waiting for someone like her to call them into service.

The Great 1913 Parade

When Paul began her work, she and her partner Lucy Burns rented a three-room basement office in Washington, D.C., below a realtor’s office and began to raise funds. Ultimately they generated over $27,000 for the parade, much of it from restless women of wealth. Within three months, they had organized an unparalleled suffrage spectacle. Virtually every suffragist in the area and many who were new to the movement, including wives and daughters of congressmen and senators, were involved.

The parade was meticulously planned. There were seven sections. The first, led by Carrie Chapman Catt, would show the worldwide reach of the suffrage movement; the second, its long historic arc from 1848 to the present day. The five others depicted how women worked together with men to build the country; women in businesses, occupations, and trades (including one thousand college women); clubwomen; state and local suffrage associations; and finally, the only participants allowed to ride along the route, the movement “pioneers,” too old to walk.

Vans were on hand to provide coffee and sandwiches to marchers. Trumpet-wielding heralds along the mile-long route would announce the arrival of the parade. Street corner suffrage speakers posted at the edge of the crowd would address onlookers who could not get a good view of the parade. The parade would conclude at the front steps of the U.S. Treasury Building, where there would be an elaborate pageant depicting an allegory of Columbia, to whom homage was paid by Charity, Hope, Justice, and Peace.

Just after 3 p.m. on March 3 the parade would begin under the shadow of the Capitol and move along Pennsylvania Avenue, turning right just before the White House to end at the Treasury Building. The day before had been quite cold, but by the time the parade began, the temperature had risen to 55 degrees. Inez Milholland, the young and beautiful equestrian queen of previous parades in New York, led off the demonstration, astride her handsome gray horse. She was followed by NAWSA officers and a horse-drawn flower-festooned cart featuring in large letters the parade’s demand for an “Amendment to the Constitution of the United States Enfranchising the Women of the Country.” The Washington Post page one article was headlined “Women’s Beauty, Grace and Art Bewilder the Capital.”

Washington D.C., once the vibrant center of African American activism, had fallen victim to the spirit of Jim Crow, and African American women were now marginalized in the suffrage movement there. Paul decided to follow NAWSA “states’ rights” policy by allowing local groups to set their own racial standards. African American suffragist Ida Wells-Barnett had come to Washington, D.C., along with sixty-five white Illinois suffragists. The head of the contingent announced that Illinois suffragists would be segregated and Wells-Barnett would not be included. Wells-Barnett declared that the parade was to be a great demonstration of democracy and she would not permit herself or her people to be excluded from it. Midway along the route of the march, she walked calmly from the sidelines, flanked by two white colleagues, and assumed her place. Her presence and that of other African American suffragists caused none of the predicted disruption.

Parade organizers turned out to have a more serious problem. They had worried that rowdy crowds, drawn to the city for the inauguration, would be difficult to control, but Chief of Police William Sylvester dismissed their concerns. Their worries turned out to be more than justified. As the parade began, enormous crowds, perhaps twenty persons deep on either side of the street, lined the sidewalks. Only a few mounted police were there to keep control, along with a small army of Boy Scouts whom the police had recruited to help.

Faced with police intransigence, Elizabeth Rogers, one of Paul’s inner circle, had convinced her brother-in-law, Henry Stimson, who was just about to leave his tenure as secretary of war, to move an Army regiment to the edge of the city in case they were needed.

Suffragists’ concerns proved well-founded. Halfway along the route, crowds broke through the police lines and closed the open space, trapping the marchers. “It was like marching into a funnel,” one demonstrator explained. Rowdies in the crowd grabbed at the women, pulled at their signs and clothes. Marchers were harassed “with all manner of smutty conversation.” The police stood by so passively that some thought they were intentionally enabling the rioters. Finally, the Army regiment arrived and pushed back the crowd to allow the procession to proceed. Hours late, the parade got to the Treasury Building, where the pageant performers, shivering in their flimsy costumes, had been waiting.

Alice Paul’s new tactics

In the next few years, Paul took a small contingent of her more radical followers into a separate organization, eventually known as the National Woman’s Party. Convinced that President Woodrow Wilson was a determined opponent of a national constitutional amendment, they first tried to get women who could vote in the western states to oppose him, but the issue of the impending war brought him back into office.

Starting in January 1917, Paul’s forces shifted to a different tactic, picketing the white house day after day, charging the president with failing to advance democracy. When the U.S. entered the Great War and they continued their picketing, they were arrested and jailed. Paul was given one of the longest sentences.

Read our interview with Alice Paul, “I Was Arrested, Of Course…”

in the February 1974 issue of American Heritage.

In jail, Paul was ever the organizer. Within two days of her imprisonment, she conducted an act of civil disobedience, breaking a window to allow in fresh air for the other prisoners. For this, she was transferred from Occoquan to the D.C. City Jail and put in solitary confinement. After two weeks, she ended up in the prison hospital, weak from confinement and with bad food. There she concocted a new tactic along with Rose Winslow, another picketer lying in a bed next to her. They decided to undertake a hunger strike, an announcement of which made the newspapers from New York to Chicago to San Francisco. A decade before, British suffrage militants and Irish Sein Fein radicals had used the practice and gained international coverage for it.

Newspapers had been eagerly awaiting the moment when American women would follow the British suffragettes’ precedent and starve themselves, and they had been disappointed that the first sentences of three days early in the picketing did not produce such a spectacle. Hunger striking was a “coveted goal of the American militant,” the Baltimore Sun and other newspapers confidently reported.”

Forced feeding was an intentionally gruesome procedure. Speaking of the prison physician sent to feed her by tying her down, forcing a tube down her nose, and pouring a foul, thick liquid into it, the famously stoic Paul recalled, “I believe I have never in my life before feared anything or any human being” until “the hour of [the doctor’s] visit.” Rose Winslow was also force-fed and kept notes, reprimanding herself: “I always weep and sob, to my great disgust, quite against my will. I will try to be less feeble-minded.” An African American cleaning woman at the prison hospital passed notes back and forth between Paul and NWP leaders on the outside.

Unable to get Paul to eat, discomfited by the negative publicity they were receiving, the jail authorities tried a new tactic — to convince her, or at least the public at large, that she was insane. This was another first — the first documented use of psychiatric diagnosis and confinement as a deliberate form of political repression in the United States, perhaps worldwide.

Psychiatrists came to the city jail from St. Elizabeth’s, the federal mental hospital, and repeatedly interviewed Paul. She suspected nothing and willingly gave her interviewers a long explanation of what she was doing and why. “I must say it was one of the best speeches I ever made,” she recalled. Searching for some mental pathology to pin on her, the doctors settled on what they considered an irrational obsession with her mistreatment at the hands of the president of the United States.

Meanwhile, other suffrage prisoners collectively composed a letter demanding to be treated as political prisoners, and to be allowed visitors. Lawyers were eventually able to serve the warden at the suburban Virginia workhouse where they were being held with a writ of habeas corpus and get the women transferred back to the D.C. City Jail. Even if not under better conditions, they were closer to supporters and observers. The lawyers convinced the court that the district’s use of the Virginia workhouse illegal. Then on November 27 the doors of the city jail were suddenly opened, and all suffrage prisoners were released, Paul among them. She had served five weeks of her seven-month sentence and had refused to eat for three. Women prisoners who were not suffragists, many of them African American, benefited from the court’s decision.

Since June, over two hundred suffragists had been arrested, nearly half of whom had served prison sentences. The NWP celebrated its victory and Paul’s release by raising almost $80,000 to refill its coffers. Five months later, a higher court threw out all of the suffrage prisoners’ sentences.

In September, the House Rules Committee, which had functioned, as one suffragist put it, as “a willing morgue” to the suffrage bill, narrowly voted to form a standing Woman Suffrage Committee to take over management of the bill. In December, the House formed the new committee, populated by congressmen from suffrage states. This dramatically increased the chances that the entire body would eventually vote on an amendment. The Senate, which already had a standing suffrage committee, reported the bill out favorably, only awaiting for it to be placed on the calendar for a full vote.

The NWP took much of the credit for these achievements. “The creation of the suffrage committee in the House proved that the pressure of women’s agitation had forced the Democratic leader to turn from his obstinate stance against national suffrage,” its newspaper, the Suffragist, boasted. But other developments were at least as important. Chief of these was the all-important electoral victory in November, at which New York, the most powerful state in the union, had amended its own constitution to give its women full voting rights. The entire New York congressional delegation now supported the suffrage bill.

Passage and ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment

The final stages of the suffrage battle were hard-fought and victory was by no means inevitable. Although the House of Representatives rapidly voted the necessary two-thirds to pass the amendment out to the states for ratification, the Senate took much longer before it followed through, interrupted by war, pandemic, and determined senatorial opposition. Only when partisan control of Congress flipped in November 1918, did the amendment’s fate pass out to the states. Again, getting the necessary three-quarters of state legislatures to ratify was incredibly difficult, made so by the opposition of most southern states. Tennessee was ultimately the thirty-sixth to ratify in August 1920.

“Nevertheless, she persisted.”

The Nineteenth Amendment barring disfranchisement on account of sex was ratified in 1920, but even after that victory, the full meaning of women’s enfranchisement continued to evolve. Southern African American women and others faced voter suppression. Over time, American women became ever more assertive in public life, and the issues that concern them moved to the center of national politics. Its legacy grows as women’s votes are solicited by political parties, even as female candidates encounter enduring misogynist taunts and sexist prejudices. Its consequences change as some women candidates for political office experience unexpected, crushing defeats, even as others win surprising victories.