In the Age of Discovery, maps held closely guarded secrets for the kings, adventurers, and merchants who first acquired them.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

Editor's Note: A number of years ago, American Heritage published reproductions of some of the most important early maps of North America. An accompanying booklet provided interesting information, but the text never appeared in the magazine. We have digitized it, updated the text, and added it here.

Ever since man scratched lines in the dust to describe the lay of the land around him, he has been fascinated by the problems of how to draw an accurate picture of his world. Very early — if not in primitive times, at least in antiquity — the map maker learned all the elements of scientific cartography. What he lacked for a long time were the proper tools to map large areas: the telescope, to determine latitude, and the pendulum clock, for longitude. In the meantime, his picture of the world fitted in between heaven above and hell below.

The transformation of the art of cartography from this ecclesiastical sandwich to a science was spurred by sheer necessity during the great Age of Discovery. Now the map maker had his telescope and clock, and could actually watch the earth grow round beneath his chased-brass instruments. Some of the tremendous excitement of that earth-rounding, mind-stretching age is clearly visible in the six maps of this portfolio. Myth and rumor retreat before the slow accumulation of facts, and the infinite care with which each map was drawn and embellished is clear evidence of its importance to the kings and statesmen and merchants and adventurers who first acquired it.

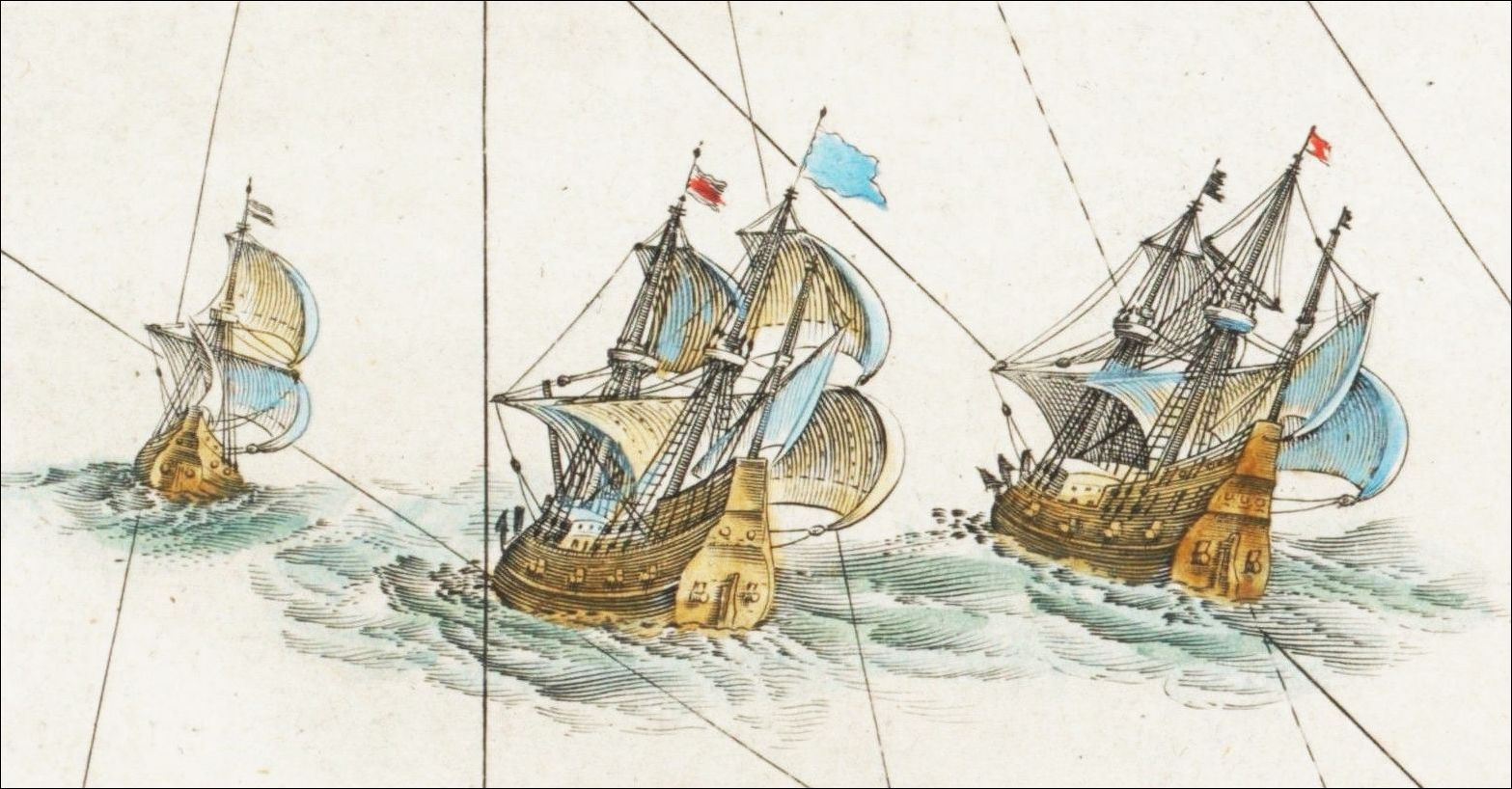

Maps made news, over and over again. The workshops of such cartographic masters as Goos and Tatton and Blaeu were popular, if pungent, places. Colors for the maps were ground and mixed on the spot, and added their odors to the smell of burnt stag antlers (for black pigment), and garlic (for which gold leaf has an affinity). The maps were meant to be displayed and discussed, to enthrall with endless detail, to please with good design—and so they do, to this day.

By 1666, when the French Royal Academy of Sciences was founded by Louis XIV, the ancient art had become a fledgling science, worthy to be a part of the Academy's curriculum. A century or so later Abel Buell, that wonderfully raffish American, could produce his picture of the young Republic with little room left for speculation or imagination. At last, we knew how to picture the lay of our land.

The years since have seen no such explosion of Cartographic knowledge, but rather a methodical refinement and filling in of details —until today. Now, when we look at his map, we can sense once more how Juan de la Cosa and his Admiral felt as they sailed off the edge of their world.

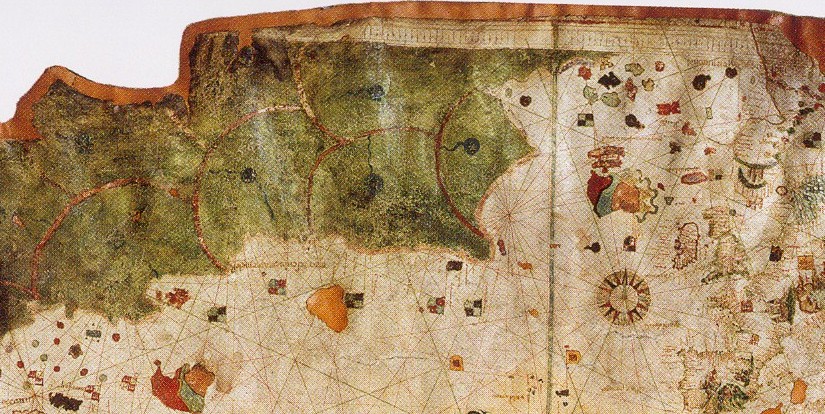

The New World in 1500, Drawn by Juan De La Cosa

This unusual chart is one of the few surviving maps directly associated with the earliest voyages to the Western Hemisphere. It was painted by Juan de la Cosa, a Biscayan pilot-navigator who sailed with Columbus on his second voyage (1493-96) in the capacity of master chart-maker and navigator of the caravel Nina.

In Spain, during Columbus's time, all maps and charts of new discoveries were kept closely guarded in the Archives of Seville; copies were issued only to the most trusted navigators and generals, and none could be engraved for wider distribution.

Today, in addition to the La Cosa map, the only other surviving charts of Columbus's discoveries are a tiny map incorporated in his armorial bearings (not really a map at all, since it defies analysis, but essentially a symbol); a rough sketch of the island of Santo Domingo, supposedly in the handwriting of Columbus himself; and three recently discovered sketches by Bartholomew, son of the Admiral, which probably depict part of the West Indies, although the islands are not carefully identified.

Juan de la Cosa, called "the most expert mariner and unrivalled pilot of his age," executed this beautiful specimen of the map maker's art on an oxhide (the white spaces here represent holes in the original hide). Recently restored, it is now 'in the Naval Museum in Madrid.

Brilliantly illuminated with figures, castles, ships, and elaborate wind-roses, the original map measures five feet nine inches by three feet two inches, and depicts the entire world as La Cosa knew or imagined it.

This section — about one-quarter of the whole — is reproduced from a facsimile, partly redrawn, and reduced in size. Much of the conventional art work is reminiscent of maps and charts of the late Middle Ages, but the Western coast of Europe, including the British Isles, is carefully drawn by the pen of a map maker who was also a navigator. To the left, across a trackless sea, is the New World—the profile of a coast then thought to be that of Asia. This terra incognita is painted green, a color customarily used by mapmakers to indicate the unknown.

At the eastern extremity of the unduly prolonged North American coastline is the legend Cavo de Ynglaterra, a promontory which experts have variously identified in the centuries since it was drawn, but one which will always remain a mystery. To the left of this, the inscription mar descubierta por ynglese, as well as the English flags along the coast, indicate that La Cosa was aware of Cabot's discoveries of 1497-98. Off South America are depicted the flags of Castile, commemorating the discoveries of the Spaniard Yafiez Pinzon in 1499. Because Cuba is shown here as an island—Columbus believed all his life that it was part of the mainland—some scholars think that this map was altered by a later hand, to incorporate discoveries that may have been made as late as 1508.

Unknown to La Cosa were the depth and limits of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. This unexplored region is neatly obscured by a vignette of Saint Christopher (thought by some to be a likeness of Columbus) bearing the Christ Child on his shoulders. The inclusion of this picture may support the theory that Columbus regarded his voyages as a holy mission to bring Christianity across the sea to the lands that did not know it. The legend under the picture reads: Juan de la Cosa la fizo en el Puerto de S. Ma. en afio de 1500 (Juan de la Cosa made it at the port of Santa Maria in the year 1500).

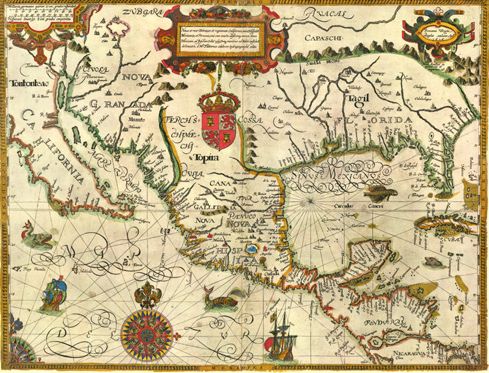

The New World in 1600, Drawn by Gabriel Tatton, engraved by Benjamin Wright

To Englishmen of the 1600's, bursting with Elizabethan vigor, the New World was a challenge — but one the Spanish had already met. What they saw when they looked across the blue Atlantic was a Spanish imperium based on the island-studded Caribbean. The English yearned to learn all they could about this rich, mysterious realm.

The map that Gabriel Tatton of England drew to satisfy his countrymen's curiosity has been called "the most beautiful map of the New World to its date." Certainly few others match it in decorative quality. It is an important map, too, because it depicts just about everything that had been discovered about the lower half of North America in the century since Columbus.

There were few, if any, Spanish maps for Tatton to copy, for the Archives and the Casa de Contratacidn de las Indias (Board of Trade) at Seville, committed to maintaining Spain's power monopoly in the New World, hoarded its knowledge. But Tatton seems to have had access to Spanish and Portuguese sources, as well as to the cartographic skills of Holland. His map is remarkably accurate. Yet the New World was still filled with enough mystery, legend, and fable to encourage the use of all the gorgeous decorative symbols that delighted the early cartographers.

Lower California (discovered by Mendoza in 1532) is correctly shown as a peninsula, though it was originally thought to be an island and was again shown surrounded by water in most maps drawn between 1622 and 1705. In the upper left corner are the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola (actually Zuni pueblos of New Mexico) and also Tiguex, where Coronado wintered in 1540 (near present-day Bernalillo, New Mexico).

Mexico, conquered by Cortes in 1521 and the main base of Spanish colonization, is very explicitly drawn, with many place names (like Acapulco) still in use today. Florida, where Ponce de Leon landed in 1513, is shown as extending to the R. de Spiritus Santo (Mississippi), discovered by Hernando de Soto in 1541. In the upper right-hand corner are shown the Mons Appalaci (the Appalachians), where — the hopeful Latin reads — "gold and silver is."

Since Spain dominated the New World in the sixteenth century, Tatton's map quite appropriately carries the royal coat of arms of the House of Castile. But it is also appropriate that this map should be the work of an Englishman, for England was about to supersede Spain in most of North America. Already Sir Francis Drake had discovered San Francisco Bay (1579) and had sacked the Spanish city of St. Augustine (1586). Soon would come the British colonies in Virginia and Massachusetts. English cartography blossomed with English exploration, and the first general world atlas in English would appear in 1606 (a British edition of the great Ortelius atlas published in Antwerp in 1570).

About Gabriel Tatton little is known, except that he spent some time in the Netherlands and described himself in the map's legend as a "celebrated hydrogeographer." His engraver, Benjamin Wright, was also English, but did much work in Italy. This outstanding example of Tatton's work was first engraved in 1600, then issued again with only the date changed (as in this copy) in 1616.

The legend at the top may be translated as: "A new and recent delineation of the lands and kingdoms of California, New Spain, Mexico, and Peru, together with an exact and absolute representation of the Gulf of Mexico to the island of Cuba and as far as the shores of the southern sea."

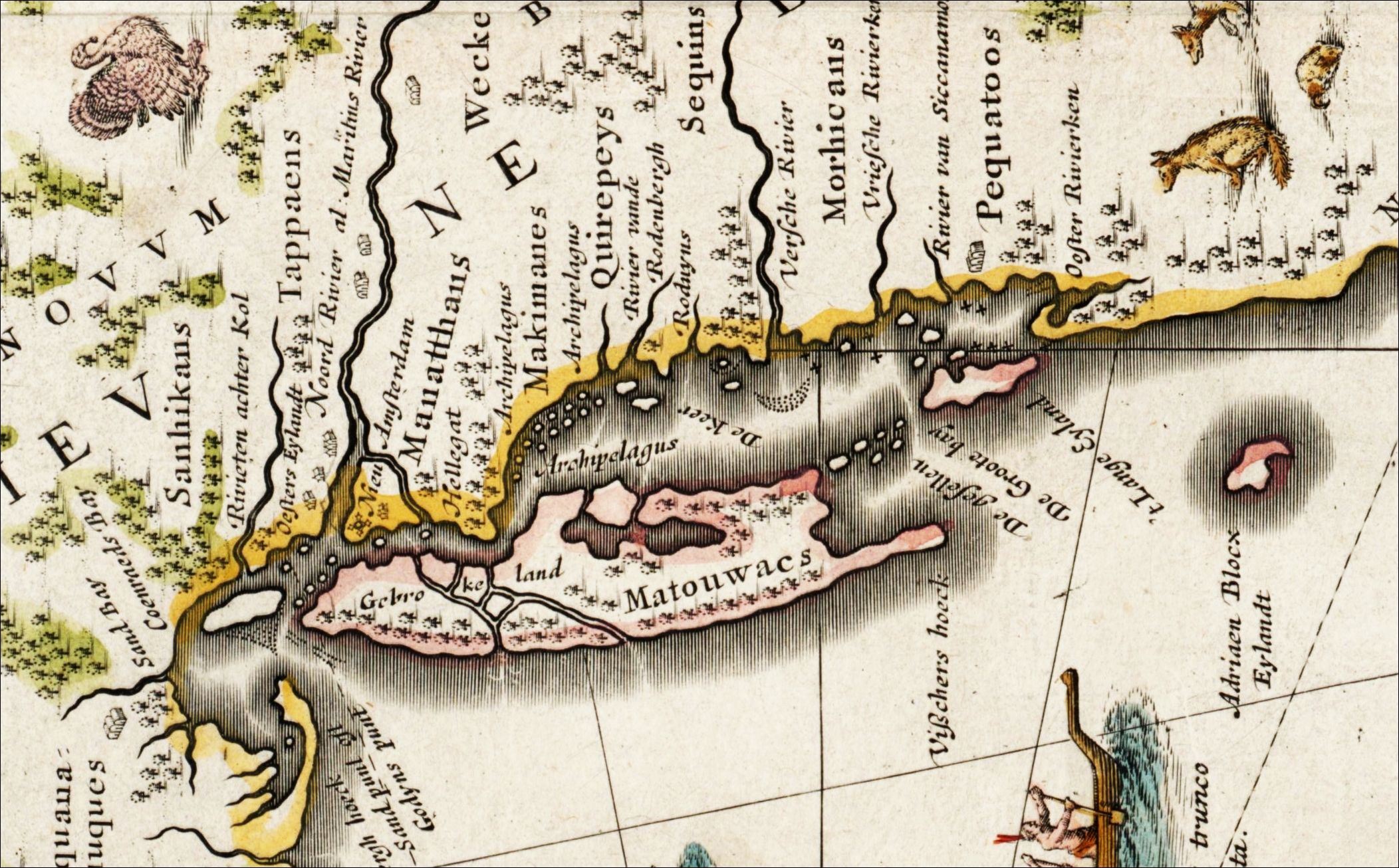

The New Netherlands and New England 1635, Drawn by Willem Janszoon Blaeu

Just after the turn of the seventeenth century, wherever the four winds blew, there was likely to be a Dutch ship scudding before them — especially if the captain believed they were blowing him toward a new route to the “Indies.” Several such captains probed the northeast coast of America between Cape Cod and Chesapeake Bay, a section where no white colonies yet had settled, even though the Spanish were entrenched in Florida and the Caribbean, and the French were moving up the St. Lawrence. The Dutch skippers saw an opportunity—and thus began the brief, glittering dreams of empire inscribed on this map.

The map is oddly oriented, with north at the right instead of at the top. Turn it sideways and you will readily recognize the familiar curl of Cape Cod and the fish shape of Long Island. Early cartographers did not always orient their maps to the north, as is customary today. Blaeu probably designed his map in this way simply because he thought it handsomer.

For William Janszoon Blaeu was as much an artist as he was a cartographer. Many collectors generally agree that the beauty of his maps has rarely been surpassed. This one was published as a double-page spread, intended to be tipped into Blaeu’s Novas Atlas. The early seventeenth century was the golden age of Dutch mapmakers, and in his day (1571-1638) Blaeu, entrepreneur of the leading publishing house in Amsterdam, was foremost of them all.

This map — remarkably accurate for its time — remained the basic chart of the North Atlantic Coast area for a hundred years. It was plagiarized by Blaeu’s contemporaries, but that was the practice of the times. Blaeu himself cheerfully copied maps by the navigator Adriaen Block (1614) and the cartographer Joannes de Laet (1630).

Blaeu’s map also illustrates his genius as a salesman. He dealt with the rough seafaring trade, but it was as important, financially, to produce handsome decorative atlases for the libraries of the gentry. An engraver named Theodore de Bry had spent a lifetime searching out drawings of the New World by men who had actually braved its dangers. It was for the genteel stay-at-homes, not the swashbuckling seamen, that Blaeu decorated his map with a smattering of De Bry’s engravings. He gave Europe glimpses of that strange bird, the American turkey; of American deer, bear, beaver and foxes; and of the savage red man and his strange canoes and stockaded villages.

Blaeu’s maps, like others of the period, were famous for their cartouches. The title cartouche at the right, small and relatively simple, is typical of his work. At the top is the Dutch coat of arms. Most of the Dutch West India Company’s colonists were Protestant Belgians; thus the title Nova Belgica. The Dutch had their own names for some parts of Anglia Nova, but they were courteous and practical enough to give the English names as well.

Blaeu’s picture of the New World was not exact, of course. Lake Champlain (Lacus Irocoisiensis) is not the right size or shape, and not in the place indicated. Long Island is shown as a small archipelago. New York Harbor is too big. And the wavy river lines representing the St. Lawrence indicate the scantiness of the seafarer’s information.

For a humorous history of the purchase of Manhattan,

see The $24 Swindle, by Nathaniel Benchley

in our December 1959 issue

The Dutch dream of a western empire began in 1608. An Englishman named Henry Hudson was commissioned by the Dutch East India Company to find a passage to China. After one unsuccessful try, Hudson turned his “Half Moon” west, and sought the passage of 40° 30’ latitude, consulting a letter and map sent him by his friend Captain John Smith.

On September 3; 1609, Hudson entered the Bay of New York and sailed upriver (Noord) as far as Albany (Fort Orange), testing the water and trading with the Indians. The trade appeared lucrative, but the testing, above tidewater, proved only that this was not the route to China; Henry Hudson sailed for home.

After him, the Dutch navigator Adriaen Block and others examined the coast as far east as Cape Cod. They came home talking of the riches of the new land and excited their merchant friends. Without official government sanction or protection, a partnership of Dutch merchants was formed in 1614 to bring the rich furs of the new continent to the prosperous burghers at home. Their trade empire — Nieu Nederlant — extended from the Delaware River (Zuyd Rivier) to Narragansett Bay (Anckerbay), but the government never laid claim to the territory. There are no territorial boundaries on Blaeu’s map.

When the Dutch ships set out, the English Pilgrims, persecuted in their own land, were languishing in the Netherlands. There they strengthened their souls, grew steadily more discontented with foreign Dutch ways, and yearned for the unfettered shores of a far-off America. In 1620 the Pilgrims made the voyage under the English flag in the little Mayflower, and eventually landed at Plymouth.

Blaeu’s map includes Nieu Pleimouth, but not the more aggressive Massachusetts Bay Colony that was established at Boston in 1630. By 1633 the English had settled a number of places as far west as Windsor on the Connecticut river, and in the same year the Dutch set up a fort near what is now Hartford, but no mention of either place is found on Blaeu’s map. No doubt the news travelled too slowly. In any event, only five places were considered civilized enough to be shown as settlements on this map: Nieu Amsterdam, Fort Orange (Albany), Nieu Pleimouth, and the French colonies of Quebec and Tadoussac.

Although the English were the last to come, their settlements flourished better than those of the Dutch, French, or Spanish. Soon the English crown began pressing its claims to all the Atlantic seaboard. First to succumb were the phlegmatic merchants of Nieu Nederlandt. Without government backing, the Dutch dream of empire was as hollow as the thumping of Peter Stuyvesant’s wooden leg. In New Amsterdam in September, 1664, Stuyvesant surrendered to a British squadron under Richard Nicolls, a protégé of the Duke of York. Although the Dutch re-conquered New York in 1673 and held it for fifteen months, their power was effectively broken in North America.

The Dutch dream of American empire endured only half a century, but it bequeathed two notable ingredients to the American heritage. One was an infusion of fine bloodlines which produced such distinguished families as the Roosevelts, the Stuyvesants, and the Van Rensselaers. The other was a rich list of place names. Adriaen Block’s Eylandt still bears his illustrious name. Hellegat still separates Long Island from Bronck’s farm. And there is a place called Gebrokeland from which the Dodgers emigrated to Los Angeles.

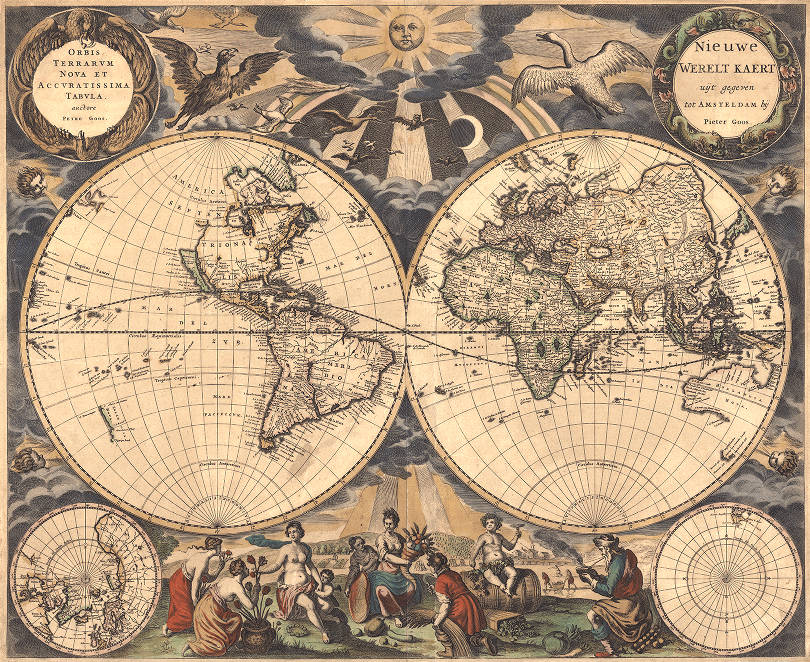

The Known Globe 1667, Drawn by Pieter Goos

By 1667, the year this lavishly decorated map was published in Amsterdam, the great age of maritime exploration was swiftly coming to a close. Only the far reaches of the Pacific, Australia, and the regions of the Arctic and Antarctic remained unprobed by the questing voyagers of England, Spain, France, Holland, and Portugal.

When their doughty captains set sail they always took along the latest sea atlas — often a Dutch Zee Atlas — containing a collection of charts which enjoyed a world-wide vogue from the time the first marine atlas was published in 1584.

This map by Pieter Goos was the introductory map of such an atlas and has special interest for two reasons. For one thing, it was compiled and published by Goos, whose works are regarded as the most beautiful sea charts of the mid-seventeenth century. Secondly, it reveals how myth, fancy, and lack of information dominated seventeenth-century conceptions of the west coast of North America, though almost all the other coastlines of the globe had by then been mapped with fair exactitude.

To appreciate Goos’s reputation it is well to remember that Dutch sea charts — as distinguished from land maps — were a great feature of the Netherlands’ prodigious map production well into the seventeenth century. In 1584, only a few years after the issuance of Ortelius’ great land atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570), a remarkable Dutch navigator named Lucas Janssz Waghenaer published the first major atlas of sea charts. Titled The Mariner’s Mirror, it contained not only working charts but sailing directions — details of important coastal areas and harbors, water depths, prevailing winds, currents, and reefs. It was greeted with such enthusiasm that sea atlases became known as “Waggoners,” and were issued in great numbers during the next century.

“As far as beauty and decorative value go in sea atlases, the maps issued by Pieter Goos are superior to others,” commented A. L. Humphreys in Old Decorative Maps and Charts. Chosen from his third collection, De Zee-Atlas ofte Water-Wereld, this typical Goos map consists of two large globes depicting the Eastern and Western Hemispheres, and two small insets of the Arctic and Antarctic regions. The Dutch inscription at upper right translates: “New World Map Published in Amsterdam by Pieter Goos.” At upper left is its Latin counterpart.

A benevolent sun beams his golden warmth upon the world below, a world whose heavens are populated with such curious examples of God’s creatures as the great white snow goose, the buzzard, the owl, and a bat or two. Conventionalized dolphins from Neptune’s kingdom surround the right-hand cartouche, while eagles (explorers of the highest reaches of the sky) spread their protective wings around the inscription at the left. From the puffed cheeks of cherubs come the four winds.

The figures at the bottom suggest an atmosphere of well-being, an expansive mood of prosperity, and homage to the glories and abundance of nature. They represent the four seasons — a mother and her child accepting flowers, a goddess with the fruits of summer, Bacchus dizzily celebrating the harvest, and Old Man Winter blowing on a bowl of coals. Behind them the landscape changes from spring to winter.

Cartographically, the two hemispheres closely resemble many other world maps of the period. This was the world as it was generally known to the layman (though some cartographers had more up-to-date information) in 1667, and where Goos lacked definite data he did not hesitate to improvise or to pick up some novelty from someone else’s map. That was what all cartographers did.

Take California, for instance. Discovered in 1533, California was first thought to be completely surrounded by water. Diego Homen’s map of 1558, however, showed the lower portion of the region correctly as a peninsula, as did Mercator (1570), Hakluyt (1587), Ortelius (1589), and Tatton (1616). Nonetheless, belief in California’s insularity continued, and Spaniards persisted in referring to the area as “the California Islands.” In 1622 a map reportedly captured by Dutch pirates in the Pacific seemed clearly to indicate that all of what is now the. state of California and Lower California was one great island.

Throughout the seventeenth century the debate continued. While new plates depicted California as an island, the same publishers almost simultaneously rolled off editions from the old plates which showed the region as a peninsula. Blaeu, for instance, shows California as a peninsula on his world maps of the 1630’s and 1640’s but as an island in the 1660’s, following the fashion of the day. Not until the early eighteenth century, when Spain renewed her colonization efforts along the Pacific coast, was Lower California’s status as a peninsula definitely established.

Remaining a mystery for another two hundred years was the strange Strait of Anian, shown on the Arctic inset where Alaska should be. Goos’s representation of the strait reflects the great dream of a short water route between Europe and Asia. North America was regarded by many merchants chiefly as a giant obstacle to Europe’s trade with the East. Their hopes for a fast and safe northern route to China fed greedily on the geographic speculations of Marco Polo. When Polo returned from his epic trek in 1295, he had reported that China was bounded on the east by a great body of water, and he spoke of Zipango (Japan) as lying somewhat to the east. The name Anian comes from Polo’s reference to a rich province of Cathay called Anin.

Sometimes called the Strait of Cathay, this much-desired seaway was probably first depicted on a map published in 1561 by an Italian named Giacomo Gastaldi. Included in map after map for the next two hundred years, the myths of this uncharted strait were not cleared up until 1728. That year Vitus Bering, a Danish captain who commanded a Russian expedition dispatched by Peter the Great, crossed Siberia and sailed along the strait, which now bears his name. Even then, heavy fogs prevented the discovery that the continents were not divided by a broad sea at that point, but by a passage only fifty-six miles wide.

But even though the northwest portion of the American continent is shown here largely as the figment of a cartographic dream, all the other coasts of the Western Hemisphere are delineated with remarkable accuracy. Pieter Goos published his map only one hundred seventy-five years after Columbus began the great westward surge of exploration, but in that brief time nearly half the globe was discovered, mapped, and occupied by the expeditions of five small European nations.

South America and the Caribbean, where the Spanish and Portuguese concentrated their efforts, look in Goos’s map much the same as they do today. The Arctic by 1667 had been explored on the Atlantic side by a series of great navigators, chiefly English, beginning in 1497 with Cabot, a Venetian commanding an English ship. Frobisher, Davis, Hudson, Batton, and Baffin all poked their prows into the ice in search of that fabled Northwest Passage to the East. In 1612 Sir Thomas Button spent a winter in the Arctic, which probably accounts for Goos’s calling the great bay Button’s instead of Hudson’s.

The French had probed deeply into North America along both sides of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. In 1535, Cartier explored the area that is now Montreal; Champlain reached the Great Lakes by 1615. These discoveries are not shown by Goos. Even the best cartographers were hesitant to incur the expense of revising their plates, which probably explains Goos’s omissions.

Further south the seaboard was liberally dotted with settlements, mostly English and Dutch, reflecting the increase in colonization in America. Look closely and you will find Nieu Pleymouth, C. de Malabre (Cape Cod), and Gebroke Land (Brooklyn). In Florida and the Southwest the Spanish remained in power. Goos makes no effort to map the unknown center of the continent, but the lower Mississippi (discovered by De Soto, 1541) is fairly accurate.

New Mexico was considered a part of Mexico and was frequently called Nova Granada, as shown. Although the Spanish expeditions of 1540 and 1598 failed to find the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, the second group did succeed in establishing a permanent colony. In 1609 Santa Fe – Real de N. Mexico (Royal City of New Mexico) on this map – became its capital. And far out in the Pacific, though Ilhas de Ladrones (Isles of Thieves) marks Magellan’s discovery of the Marianas in 1521, there is only a vast watery gap where our fiftieth state now stands: Captain Cook would not find Hawaii until 1778.

New France 1745, Drawn by Reiner Ottens

In 1745, when the Dutch cartographer Reiner Ottens limned a map of New France, the French empire in North America was enjoying its moment of greatest glory. It was a time when France held control over an immense area that stretched from the Great Lakes south to Florida, and from Newfoundland (here labeled “l’Isle de Terre Neuve”) west to the mysterious and hardly explored plains beyond the source of the great Mississippi. Even the vast Spanish possessions in North America were dwarfed. England maintained only a thin line of settlements on the Atlantic coast (not very accurately rendered here); passing through the little-known far north, where Labrador is confused with “Lands of the Great and Lesser Esquimos,” The English could reach a few trading posts they maintained in the bleak Hudson Bay region. Few would have thought it conceivable that in another eighteen years New France would no longer exist.

The French empire in North America had already been established for over two centuries when this map was printed. In 1534, the first of a long line of great French explorers, Jacques Cartier, sailed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, passing along the west coast of Newfoundland to Prince Edward Island (here, “I. de S. Jean”) and the Gaspe Peninsula. The following year he returned to make more extensive surveys, this time venturing up the St. Lawrence River as far as site of Montreal.

The claims of France in the New World were further strengthened by the discoveries of Samuel de Champlain, the royal geographer for King Henry IV. Champlain explored Canada from the Bay of Fundy (“Baye Francois”) to Lake Huron, and south to Lake Champlain — which cartographer Otten called “Mer des Iroquois,” after the powerful Indian nation that ruled the region. In 1608 Champlain established a settlement at Quebec, and three years later founded a trading post at Montreal, on the site of an Indian village called Hochelaga.

The prosperity of the rapidly burgeoning French empire was based mainly on the abundance of that small and pleasant fur-bearing mammal, the beaver. Fur-trading posts sprang up all along the St. Lawrence and its tributaries; by the middle of the seventeenth century, French explorers and, close on their heels, the inevitable fur traders were venturing into the interior. In 1671, St. Lusson, in the presence of representatives of fourteen Indian tribes, performed at Sault Ste. Marie the feudal rite of taking possession in the name of Louis XIV of the Great Lakes area as well as of all land to the west.

Two years later, Louis Joliet and Jacques Marquette descended the Mississippi, turning back once they were convinced that the river flowed not into the Atlantic or the Gulf of California, but into the Gulf of Mexico. La Salle, after earlier explorations in the Illinois country, traveled down the Mississippi to its mouth in 1682 and claimed the entire river basin for Louis XIV, naming it Louisiana in his honor. As the historian Francis Parkman wrote, describing that ceremony in the river delta: “The fertile plains of Texas; the vast basin of the Mississippi, from its frozen northern springs to the sultry borders of the Gulf; from the woody ridges of the Alleghanies to the bare peaks of the Rocky Mountains — a region of savannahs and forests, sun-cracked deserts, and grassy prairies, watered by a thousand rivers, ranged by a thousand warlike tribes, passed beneath the sceptre of the Sultan of Versailles; and all by virtue of a feeble human voice, inaudible at half a mile.”

In 1684, La Salle returned to the Gulf of Mexico, this time with a party of colonists. Near present-day Matagorda Bay on the Texas coast the French explorer founded a tiny settlement. But France’s first attempt to colonize the Gulf region ended tragically. La Salle was murdered by his own men, and — as Ottens remarks in a notation on the map — most of the remaining colonists were killed by Indians.

The two all-powerful institutions in New France were the royal government and the Roman Catholic Church. From the year 1612 on, when the first Recollet friars landed in Quebec — they were followed soon after by the Jesuits — missionaries played a prominent role in the life of the colony, exploring vast stretches of unknown territory and striving zealously to convert the Indians. One of the most important missions was St. Ignace, founded by Pere Marquette at the straits of Michilimackinac, the important north-south water route which connected Lake Huron with Lake Michigan (called by the French “Lac des Ilinois”). Also well known was the nearby mission of Ste. Marie du Sault (sault is Old French for saut, or waterfall), which lay on another principal waterway used by the Indians, the rapids-choked river connecting Lake Huron with Lake Superior — today the site of the famous Soo canals.

Reiner Ottens, the man who drew this handsome and infinitely detailed map, was a member of a family of Dutch map publishers active in Amsterdam during the first half of the eighteenth century. His father, Joachim Ottens, worked for the renowned and prolific mapmaking house of Frederick de Wit before starting his own firm. Thus the Ottens family was directly linked to the century-long period stretching roughly from 1570 to 1670 when the Low Countries produced the world’s best cartography and the most accurate and beautiful maps of the time.

After the death of Joachim, his widow carried on the business with her two sons, Reiner and Josua. Like many other cartographers of their time, the Ottens brothers copied extensively from the work of earlier map makers. Competition was keen, and few map publishers had the time or inclination to revise old maps and engrave new plates. By the eighteenth century the standards of Dutch cartography had declined, and much of the new and interesting geographical material was now to be found on French maps. But derivative as the Ottenses may have been, they were also vastly enterprising. Their tremendous eight-volume Atlas Maior, which was printed sometime before 1740, contained no less than eight hundred thirty-five maps. In 1745 they published another and much smaller atlas, with thirty-three charts of Europe, parts of Africa and Asia, and the Western hemisphere.

Although Reiner Ottens’s map is dated 1745, its geographical knowledge is by no means always contemporary. It is similar to many French maps of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Ottens apparently relied on the plates of Nicholas Sanson d’Abbeville, geographer to Louis XIV; he also seems to have profited from information contained in several of Guillaume Delisle’s maps of North America. Like Delisle, Ottens traces the correct course of the Mississippi, places Santa Fe to the east of the Rio del Norte — or Rio Grande, as it is now known — and comments on Indian tribes hostile to the Spanish as well as on the abundance of cattle on the Texas plains. Both cartographers take pains to show Louisiana — which then included Florida — as a territory separate from the rest of New France. However, Ottens does not seem to have used Delisle’s famous map of 1718, which included, among other things, the correct size of Lake Champlain and the important French settlement of Natchitoches on the Red River of Louisiana.

Since Ottens printed some of Delisle’s maps with acknowledgment, we know that he was well acquainted with the work of the great French cartographer, whose information on North America was a chief source for most eighteenth-century map makers.

What Ottens sacrificed in originality he more than redeemed through colorful presentation and minute attention to detail. As his knowledge of the northern and western reaches of the continent was understandably limited, Ottens filled in the blank spaces with charming if somewhat idealized sketches of birds, animals, and aborigines. His pictures of Indian villages and an Indian ceremony (lower left) were probably based on the well-known engravings of Florida and Virginia natives done in the late sixteenth century by the Flemish artist Theodore de Bry. Nor did Ottens leave untenanted that emptiest of all spaces, the sea, populating it with a multitude of sailing ships and even including a naval battle south of Bermuda.

With a good deal of accuracy, Ottens was able to place major Indian tribes in their accustomed haunts. He indicated the wilderness outposts which formed a frail network of protection for French territory against the encroachments of the English and Spanish, as well as of the ever-hostile Indians. Canoe portages—the turnpike interchanges of that frontier era—were likewise marked.

Especially interesting are Ottens’s many brief notations of a geographical, historical, or anthropological nature some of them based on erroneous information. For instance: “Sources of the Mississippi in the vicinity of 50 degrees northern latitude and 275 degrees longitude in very marshy country” (like many early cartographers, Ottens apparently based the prime meridian at Hierro in the Canary Islands, eighteen degrees west of the present prime meridian at Greenwich, England. He thus placed the headwaters of the river in Canada, several hundred miles to the northwest of the actual source, Lake Itasca in Minnesota); or again — west of Virginia — “The Tionontatecaga, who live in caves to protect themselves from the extreme heat.”

It is altogether appropriate that Ottens selected a map and view of Quebec for the cartouche of his map. This city, the seat of the royal government, was also the center of learning in New France and occupied an important strategic location. In the words of a 1663 Jesuit account, “Quebec . . . is the key to North America.” It was the most impressive capital north of Mexico City; it was also the most heavily fortified. But. while Otten’s view of the city agrees with others of the period, he does not seem to have recognized the steepness of the cliffs on which Quebec is built.

After the St. Lawrence River, the most important gateway to the interior of New France was the mouth of the Mississippi and the surrounding Gulf coast. This area was the scene of conflicting territorial claims of the three major powers: each realized that to possess it was to control a gigantic chunk of the North American continent. Although the coast was dotted with forts and trading posts, such as Pensacola and Biloxi (spelled by Ottens, “Bilochy”), the French never settled large numbers of colonists here, preferring the less humid climate of Canada. Strangely enough, New Orleans—which was founded in 1718—does not appear on this map, although Ottens refers to the settlement in his 1745 atlas. Despite its consequence as a port, New Orleans grew slowly and under French rule never realized the potentialities of its strategic location. In general, the Louisiana section of Ottens’s map is less reliable than the Canadian; the Spanish, who had made the most accurate surveys of the region, would not permit them to be seen or copied.

The conflict between France and England for supremacy in North America—that vast, interminable struggle in the wilderness that would eventually eradicate all but the merest traces of the French empire in the New World — began late in the seventeenth century and continued intermittently for almost eighty years. If the French had the advantage of centralized control (as opposed to the loosely connected and always bickering British colonies), a carefully placed network of forts, and powerful Indian allies, these were more than balanced by the numerical superiority of the English colonial population and the formidable strength of the British Navy.

For years it was a largely inconclusive conflict. Territory was endlessly disputed, gained with a battle, lost with a pen stroke on a treaty. King William’s War, Queen Anne’s Wax, the Yamassee War — even the names of that bitter and dreary succession of frontier struggles are now all but forgotten. But for New France, the end came with a startling suddenness. In 1758, during that final struggle known as the French and Indian War, the great Cape Breton Island fortress of Louisbourg — another remarkable omission on Ottens’s map — fell to the British. The next year Quebec itself, the “key to North America,” was lost after Wolfe’s famous victory on the Plains of Abraham, and in 1760 Montreal, the last major French stronghold on the continent, capitulated without a struggle. When the final shot had been fired, and the inevitable treaties signed, all that remained to France of her once proud empire in Canada and Louisiana were two dots of sand off the south coast of Newfoundland, St. Pierre and Miquelon.

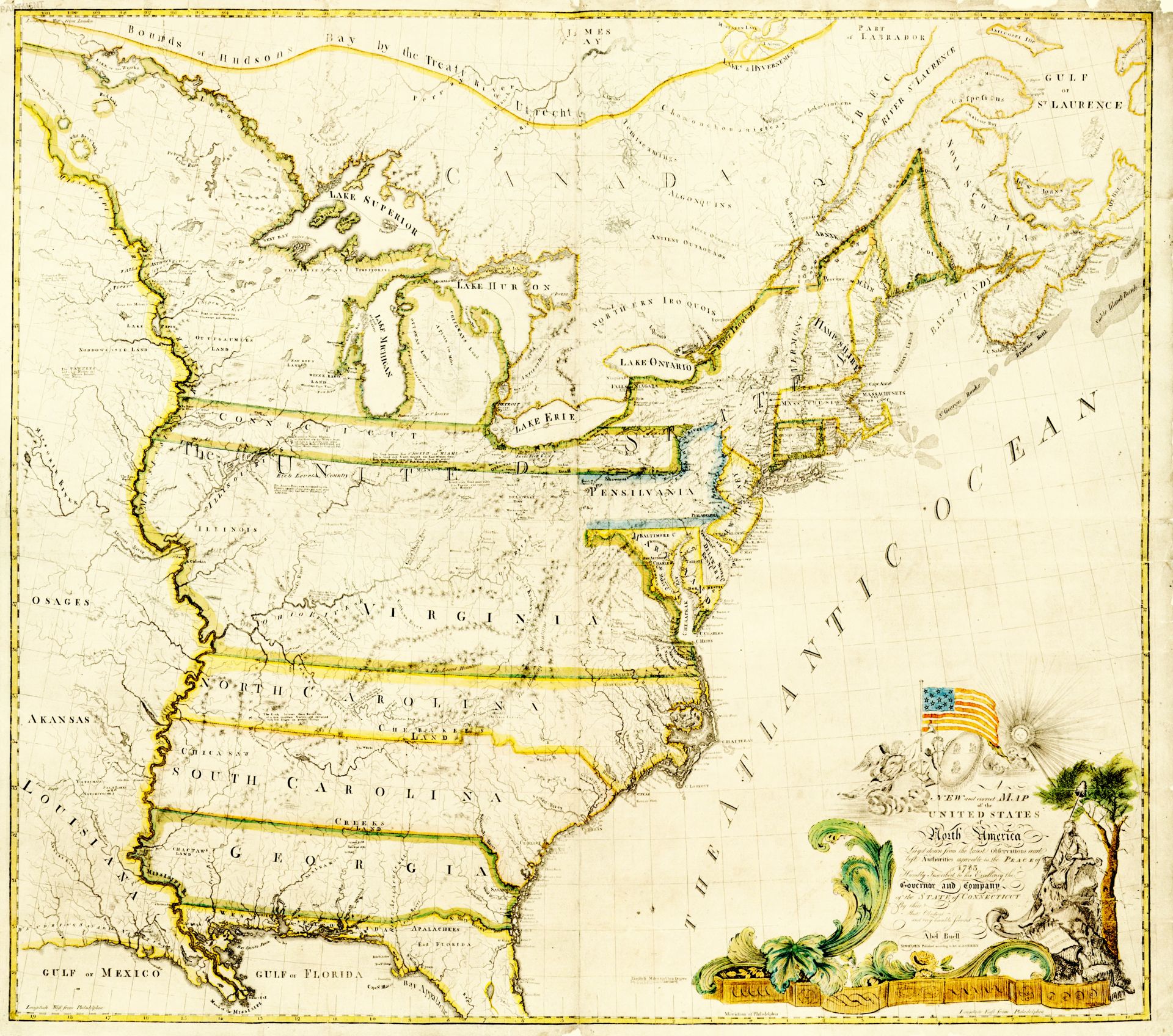

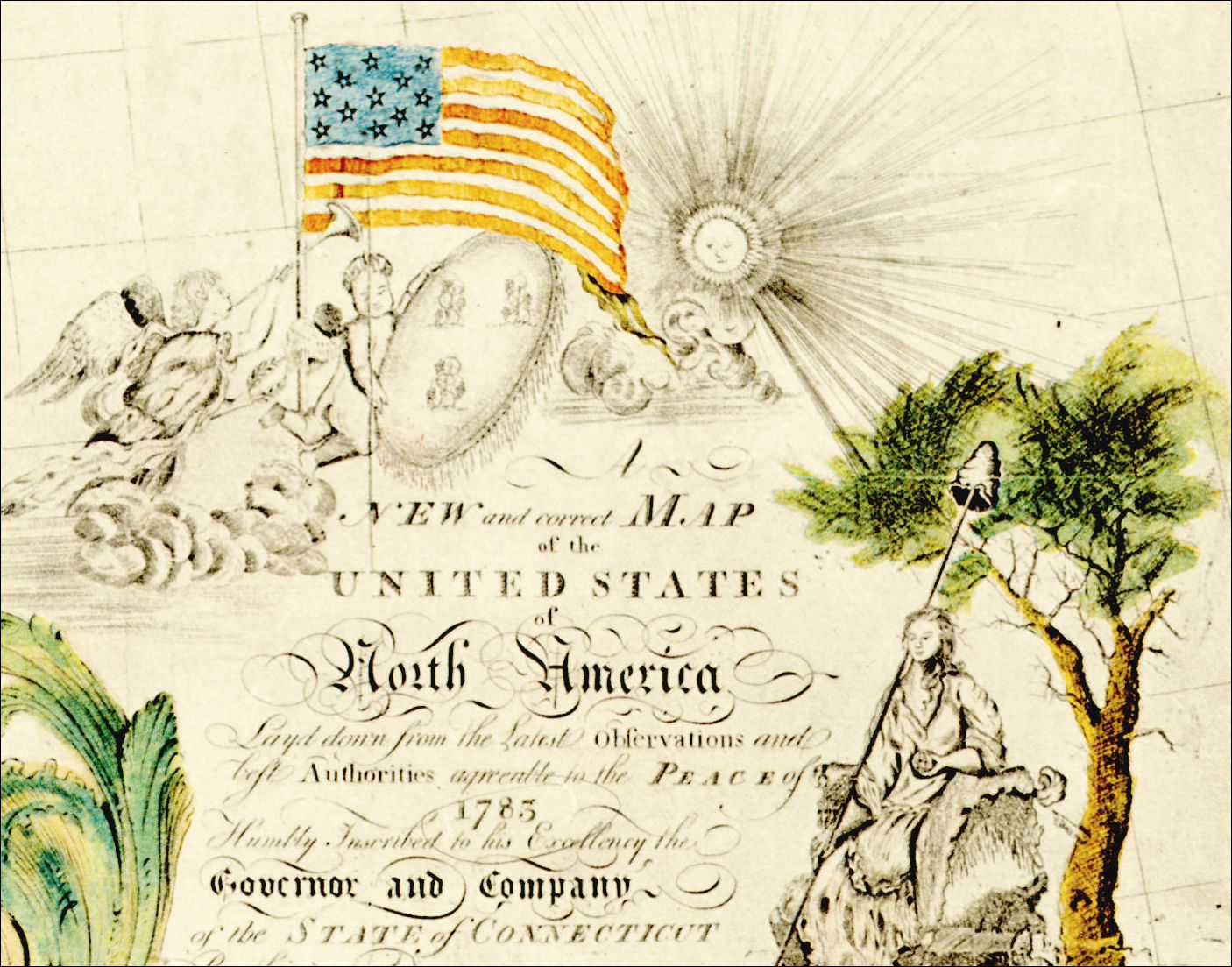

The First American Map of the United States 1784, Drawn by Abel Buell

As late as 1961 only three of the maps were thought to exist. A fourth (shown here) was discovered in 1962 by the staff of the New Jersey State Historical Society, in whose archives it had apparently lain unnoticed for years.

The map is made up of four sheets, each printed from a separate copper plate. Overlapping allowed for pasting the four together, making the over-all size of the engraved surface 41 by 46516 inches. The fact that the map was probably intended to be hung on a wall may well account for its rarity. Exposed to sunlight, dust, and dampness, wall maps soon fade and are discarded, especially when new and more accurate (if generally less interesting) ones come along to replace them.

The map was entirely the work of one man, and a remarkable individual at that. A restless, unstable, ambitious tinkerer, Abel Buell was a practical genius in the best Yankee tradition (and occasionally, the worst). He was born in Killingworth, Connecticut, on February 1, 1742. In his youth he was apprenticed to a goldsmith, and eventually became one himself. Unhappily, he also turned his artisan’s skills to counterfeiting; in 1764 he was convicted of altering Connecticut paper money from two shillings six pence to thirty shillings. In prison one ear was cropped, and he was branded with a C on his forehead.

Soon free again, he began producing the first type faces known to have been cut and cast in the English colonies. The American Philosophical Society inspected specimens of his type and reported on them favorably. The Connecticut Assembly loaned him £100 to start a type foundry. But like so many of Buell’s ambitious projects, this one ended in failure. Presently he became an engraver, the first in the colony of Connecticut. His new trade did not exactly make him wealthy, and in 1774, he found himself so mired in debt that he sailed for West Florida—then an English possession—leaving his wife to cope with his creditors. Apparently she did, for three years later he was able to return home. Suddenly he seemed busier than ever. He dabbled in privateering. He became an auctioneer. He owned packet boats sailing between New Haven and New London. He returned to producing type. And once the Revolutionary War was officially over, he set to work engraving a map of the United States that would become his enduring monument.

In later years his activities were no less varied. Ironically enough, Abel Buell, the onetime counterfeiter, was hired to coin copper money for the state of Connecticut. He attempted to set up a cotton manufacturing plant, designed a machine for planting corn and onions, and exhibited to the public a “wonderful Negro who is turning white.” In 1799, during the undeclared naval war with France, he turned up in Hartford, where he advertised swords, dirks, pikes, and military flags. But Abel Buell’s fortunes, never as bright as his many talents, were on the wane. Moving to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, about 1803, he set himself up as a goldsmith, the trade he had learned as a youth and which he had practiced sporadically throughout his life. Little is known of these last years, but they were evidently unhappy ones. When he grew too old to make a living, he returned a final time to New Haven. On March 10, 1822, a local newspaper reported, “Mr. Abel Buell, aged 81 years, an ingenious mechanic, [died] at the Alms House in this town.”

Though Abel Buell’s destiny was a lonely and forgotten pauper’s death, his life can by no means be counted a failure. His achievements were many, and at least one of them, the compilation and engraving of the map of the United States, was of considerable importance. To be sure, the map had its shortcomings. In some of the detailing haste is evident — the lettering is often crudely rendered — and in matters of geographical proportion, Buell was evidently none too sure of himself. His native Connecticut, for instance, seems flattened in a vise between New York and Rhode Island; Pennsylvania suffers a similar compression, while distances in the southern portion of the map have been almost grotesquely foreshortened. And yet, as Buell’s biographer, Lawrence C. Wroth, points out, “If his map is to be considered as the work of a self-taught country engraver, not especially well educated and not trained in geographical observation, it must impress everyone who examines it as a tour de force that compels admiration.”

According to the inscription on the map, it was “Layd down from the Latest Observations and best Authorities ......Buell made no claim for himself as the actual collector of the data which he presented. Comparison with other well-known maps and geographical texts with which he must have been familiar shows that he relied on some of the best material available at the time.

One obvious source of information was John Mitchell’s “Map of the British and French Dominions in North America . . .” published in London in 1755, on the eve of the French and Indian War. This map by a man who had been for some years a resident of Virginia was used by the British Army throughout the climactic struggle with the French in America, and it served American and British diplomats well at the. peace conference in Paris after the end of the Revolution.

A second probable source was “A general Map of the Middle British Colonies, in America...” which also appeared in 1755, and was published in Philadelphia. The cartographer was Lewis Evans; the publishers, Benjamin Franklin and David Hall. Evans’s volume, Geographical Essays, appeared with the map.

Finally, in 1778, there was published in London “A New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland and North Carolina” by Captain Thomas Hutchins—a New Jersey-born officer in the British Army who may well have known Abel Buell, for both were living in the West Florida settlement of Pensacola at the same time.

A few examples will illustrate just how much Buell depended on the maps of Mitchell, Evans, and Hutchins. At the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, for instance, both Hutchins and Buell show the same landmarks—Yellow Bank, Fort Massac, and Large Cedars. Both show the great rapids of the Cherokee (now Tennessee) river called Muscle Shoals, a natural phenomenon first cited by that name on Hutchins’s map. Moreover, between the Shawanoe (Cumberland) and Cherokee rivers there appears on both exactly the same notation: “The Lands between these Rivers, are of a most excellent Quality, and inter-mixed with low Ridges; or rather gradual Risings.” Similarly, Buell borrowed small but significant details from Mitchell—as well as imitating the general outlines of the older map. In 1755, Mitchell noted south of Lake Erie “The Seat of War, the Mart of Trade, & chief Hunting Grounds of the six Nations, on the Lakes & the Ohio,” which Buell shortened to “The Mart of Trade and Chief Hunting Grounds of the Six Nations.” Finally, the maps of Evans, Hutchins, and Buell all note the word “Petroleum” east of Venango on the Allegheny River. The presence of oil in western Pennsylvania was apparently a matter of common knowledge more than a century before Edwin Drake drove the first well there in 1853.

To the modern viewer, the face of America that Buell’s map presents may seem jumbled and unfamiliar. Here, Maine is divided into two parts; Vermont appears an extension of New York; Connecticut leapfrogs into the West; Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia extend their boundaries to the Mississippi, while the Louisiana Territory and Florida — which the British relinquished after the Revolution—are held by the Spanish Empire.

As British colonies, many of the original thirteen states had been granted land as far west as the Mississippi (some wishful charters extended their claims to the “South Seas,” meaning the Pacific); with the end of the Revolution, these states hastened to reaffirm their rights to these vast but largely unsettled regions. Since knowledge of the geography beyond the Appalachians was still uncertain at best, it was inevitable that claims would conflict. Nowhere was the situation more tangled than in the Northwest Territory, that quarter-million-square-mile area bounded on the south and east by the Ohio River, on the west by the Mississippi, and on the north by the Great Lakes and Canada.

Virginia claimed all of it, and the region that is now Kentucky as well. Massachusetts claimed a wide strip (not shown on the Buell map) that, extended across present-day Michigan and Wisconsin. Connecticut, in her turn, could show a royal title dating back to 1662 to all land between the 41st and 42nd parallels from Pennsylvania to the Mississippi. (In Buell’s map, the’ Connecticut claim embraces a large portion of Pennsylvania, but he was in error—for this disputed land had been awarded to the latter state two years before he published his map.) This confusion of claim and counterclaim was largely academic; until the signing of the Jay Treaty in 1794, most of the Northwest Territory was actually controlled by the British, who stubbornly held on to such key border outposts as Michilimackinac, Detroit, and Niagara — a fact which Buell, perhaps for patriotic reasons, chose to overlook.

By the time Buell finished his map, the situation in the Northwest Territory had already begun to clear up. In 1784, Virginia ceded to the government all land north of the Ohio (Kentucky did not become a separate state until 1792). Massachusetts relinquished her claim the same year, and Connecticut shortly afterward gave up all but a relatively small tract in what is now northwestern Ohio. To this area, called the Western Reserve, she retained property rights until 1795.

In parts of the East, however, boundary conflicts were just as confused — as a glance at Buell’s map will indicate. Vermont, for example, was claimed by no less than three states: Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York. It wanted no part of any of them. In 1777, delegates from fifty-one towns on the western side of the Green Mountains met and created an independent state tentatively named “New Connecticut, alias Vermont.” Though Massachusetts and New Hampshire had recognized the new state by the time Buell published his map, New York still persisted in her claim, and it was not until 1791 that Vermont was formally admitted to the Union.

Meanwhile Maine presented another problem. As Buell indicates (not altogether accurately), it was in effect divided. The southern portion belonged to Massachusetts—it was 1820 before Maine became a state—while the wedge-shaped area in the north, here bordered in green, represents the 12,000 square miles of wilderness which the United States and Britain would quarrel over for close to sixty years, a dispute which ended only with Daniel Webster’s clever settlement in 1842.

Buell’s map was not the first of the United States done after the Treaty of Paris; it was merely the first engraved in America by an American (although a Pennsylvanian, William McMurray, had advertised a similar map in August, 1783, his did not appear until December, 1784, nearly nine months after Buell’s). In London, at least four maps showing the boundaries of the new nation had already been published, while the name “United States” had appeared on maps as early as 1778. Even so, Abel Buell’s achievement was remarkable. An ingenious Yankee who saw a need and immediately set out to fill it as best he knew how, he exemplified with this map that enterprising spirit which early in the life of the American republic marked it as a nation to be reckoned with.