Some delegates at the Constitutional Convention wanted a strong executive, while others feared the American president might become a king.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

Editor's Note: One of the preeminent historians of our time, William Leuchtenburg published his first essay in American Heritage in 1957. We were saddened to hear of his passing earlier this year, but also delighted he published a last book of essays entitled, Patriot Presidents: From George Washington to John Quincy Adams. We thank Oxford University Press for allowing us to adapt one of the essays.

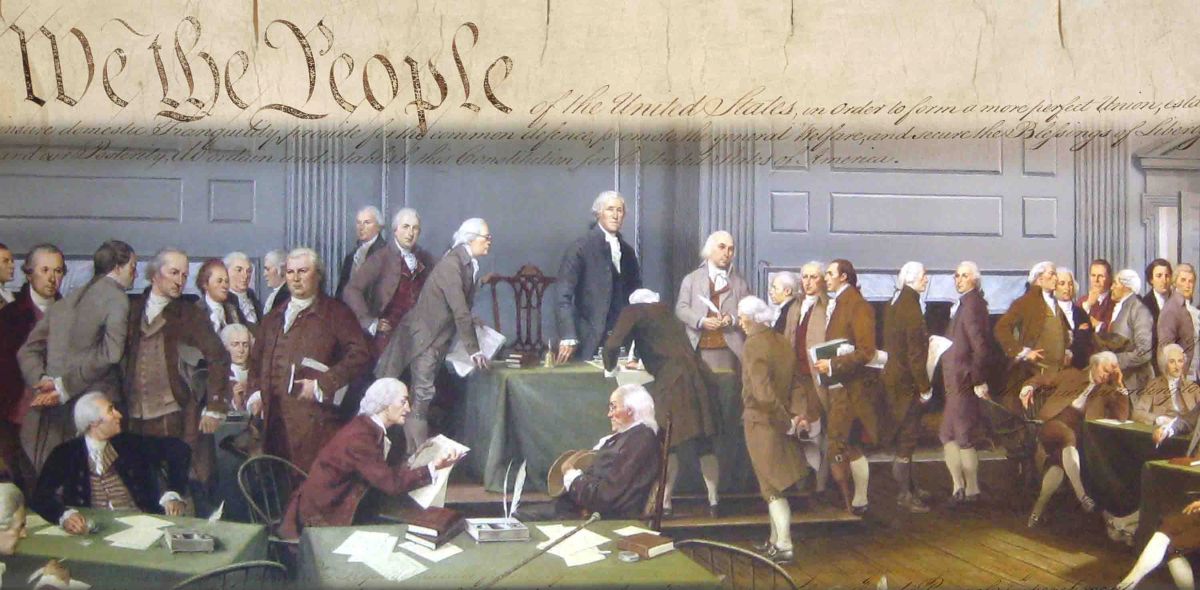

At no time in our history has there been so illustrious a gathering as the corps of delegates who came together in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia late in the spring of 1787 to frame a constitution for the United States of America. After Thomas Jefferson, the country’s envoy in Paris, ran his eyes over the roster, he wrote his counterpart in London, John Adams, “It really is an assembly of demigods."

Yet, distinguished though they were, the delegates had only the foggiest notion of how an executive branch should be constructed. Not one of them anticipated the institution of the presidency as it emerged at the end of the summer.

One frightful goblin haunted their deliberations. The study of history — ancient to modern — instructed them that republics were always short-lived, and they feared that America might quickly adopt kingship.

“I am told that even respectable characters speak of a monarchical form of Government without horror,” the nation’s foremost patriot, George Washington, reported with a shudder. “From thinking proceeds speaking, then to acting is often a single step. But how irrevocable and tremendous! what a triumph for our enemies to verify their predictions!”

Jefferson shared Washington’s dismay at the prospect. From Paris, commenting on his experience of three years abroad, he wrote the general: “There is scarcely an evil known in these countries which may not be traced to their king as its source, not a good which is not derived from the small fibres of republicanism existing among them. I can further say with safety, there is not a crowned head in Europe whose talents or merits would entitle him to be elected a vestryman by the people of any parish in America.”

Little wonder that during the convention proceedings the delegates heard a young lawyer from Philadelphia, James Campbell, boldly urge in the (approving) presence of Washington. “May every proposition to add kingly power to our Federal system be regarded as treason to the liberties of our country.” Decades of struggle against royal governors had taught Americans that the executive was their enemy, that legislative assemblies spoke for the people.

Hence, in the aftermath of the rebellion against George III, most states had adopted constitutions reflecting the travail of the thirteen colonies. Governors under most of the new state charters were the weakest of sovereigns. They were elected by legislatures, for only a single year; exercised what limited powers they had under the oversight of a council of state chosen by the legislature; and were denied such traditional prerogatives as the veto. New Hampshire would not even tolerate the loathsome word “governor.” As James Madison reminded the delegates, “Experience had proved a tendency in our governments to throw all power into the legislative vortex,” so that state executives were “little more than cyphers.”

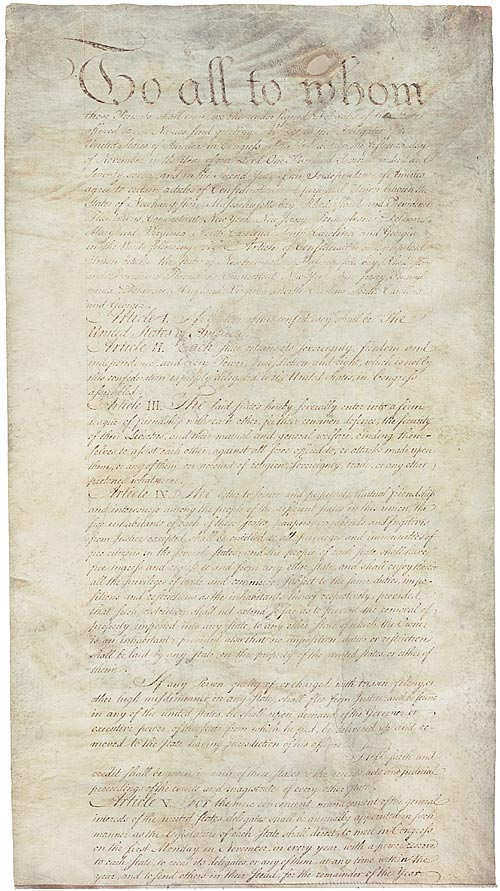

The Articles of Confederation drafted during the Revolution made no mention at all of an executive. The nonentity designated as president of the Continental Congress had so little authority that when he was absent a clerk took over. He could not make appointments, negotiate treaties, command the armed forces, veto legislation, or pardon, and he did not even have the guarantee of a fixed salary.

By 1781, however, a rudimentary executive wing had emerged, with posts filled by men of exceptional ability: Robert Morris as Superintendent of Finance, Robert R. Livingston and then John Jay as Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and Henry Knox as Secretary of War. None of these men, though, was supervised by the figurehead who was called president.

Yet a good number of the Framers arrived in Philadelphia disenchanted with legislative supremacy and committed to the creation of a potent national government headed by a vigorous executive. They wanted a regime strong enough to cope with outbreaks such as Shays’s Rebellion — an uprising of debtors in western Massachusetts led by a former captain in the Continental Army — that had prevented courts from convening in Northampton and Worcester and had attempted to seize a federal arsenal.

George Washington, who saw this insurrection as proof of the “want of energy” in state governments, railed, “We are fast verging to anarchy and confusion!”

Despite the fulminations of the Framers against George III, the idea of a strong executive struck a responsive chord. The theorists they read — Blackstone, Locke, Montesquieu — all accepted executive authority. John Locke had written, “The good of the society requires that several things should be left to the discretion of him that has the executive power . . . to be ordered by him as the public good and advantage shall require; nay, it is fit that the laws themselves should in some cases give way to the executive power.”

Monarchy was the form of government with which Americans were most familiar and hence an inescapable template. Every one of the delegates had been born under the British Crown. South Carolina delegate Pierce Butler had first come to America as an officer of the redcoats. Wherever they looked in the world, they saw a dominant leader — Catherine the Great ruled Russia, and in Prussia Frederick the Great had died only a year before. New York’s constitution authorized a popularly elected governor who was given military command, and Massachusetts, heeding the insistence of the essayist Theophilus Parsons, established a “supreme executive magistrate” personified by John Hancock and James Bowdoin.

Some Americans even dared to think the unthinkable. “Shall we have a king?” John Jay had asked Washington in 1786. A year later, Mercy Otis Warren, who was writing a history of the Revolution, expressed alarm that “the young ardent spirits,” especially “the students of Law and the youth of fortune and pleasure,” were “ready to bow to the sceptre of a King.” Well along in the proceedings at Philadelphia, a North Carolina delegate ventured that it was “pretty certain that we should at some time or other have a King.”

Yet no one at the convention ever determinedly broached the question of monarchy, not even New York’s Alexander Hamilton, who advocated life tenure for the executive and adoption by America of the British style of governance that he thought was the best in the world.

Still, there was suspicion that the delegates were plotting to impose a king on the new republic. Rumors gained credence that the convention planned to call to a throne in America the Bishop of Osnabrück, a Hanoverian cleric who was the second son of George III. The delegates regarded this alarum so seriously that, for the only time during the proceedings, they transmitted information to the press, stating, “‘Tho we cannot, affirmatively, tell you what we are doing; we can, negatively, tell you what we are not doing — we never once thought of a King.’”

In the first week of September, when the Framers took up the question of the presidency for a final time, they revised many of their previous decisions, especially in order to adjust the imbalance between the chief executive and Congress. They authorized the president to appoint major officials, including ambassadors and Supreme Court justices, and they turned over to him the right to make treaties, though with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate. By agreeing to Pinckney’s proposal that the president “shall, by Virtue of his Office, be Commander in Chief of the Land Forces of U.S. and Admiral of their Navy,” they gave him immense power to determine strategy in wartime and in other national emergencies, thus establishing the principle of civilian supremacy over the military.

The convention stopped well short of investing him with monarchical authority, however. Sir William Blackstone would have been shocked to learn that the Framers denied the president what, in his seminal Commentaries on the Laws of England, he had seen as a fundamental privilege of rulers: “the sole prerogative of making war and peace.” Instead, delegates lodged the war power with Congress.

Jefferson rejoiced in this “effectual check to the dog of war by transferring the power of letting him loose, from the executive to the legislative body,” and a decade after the Philadelphia meeting Madison explained: “The constitution supposes, what the History of all Govts demonstrates, that the Ex. is the branch of power most interested in war, & most prone to it. It has accordingly with studied care vested the question of war in the Legisl.”

This feature, though, proved less decisive than it seemed. Madison won acceptance for substituting “declare” for “make” war, thereby “leaving to the Executive the power to repel sudden attacks,” and also eliminating the possibility that “make” might be thought to mean “conduct.” Furthermore, in only five instances over the next two centuries were US armed forces employed as a consequence of a Congressional declaration. Instead, presidents seized the initiative or involved the nation in an imbroglio so deeply that Congress had no choice but to go along.

The Committee on Postponed Matters made a critical move in taking choice of the president from Congress and vesting it in an “electoral college.” It refined a proposal that James Wilson had aired earlier by requiring that electors meet in their respective states. Thus “college” was a misnomer from the outset; it was never intended to be a deliberative body that debated the merits of candidates.

The Electoral College, historian Gordon Wood has concluded, “was an ingenious solution to delicate and controversial political problems, and the fact that it has rarely worked the way it was intended does not change its ingeniousness.”

Never did the Framers seriously entertain direct popular election of the president — not simply, as is so often said, because they abhorred democracy. The great expanse of the country, Virginia patrician George Mason contended not unreasonably, made it “impossible that the people can have the requisite capacity to judge of the respective pretensions of the Candidates.” Gloucester fishermen in pursuit of cod on the Grand Banks could not imagine the lives of Philadelphia cordwainers or South Carolina indigo planters, let alone pass judgment on the political figures in those orbits.

Furthermore, delegates from small states feared that the winner of a plebiscite would always come from one of the more populous states. Indirect election also militated against the emergence of a demagogue inflaming or truckling to the masses. There was in addition, though, a strong current of contempt for the judgment of the hoi polloi. Mason thought “it were as unnatural to refer the choice of a . . . chief magistrate to the people, as it would be to refer a trial of colours to a blind man.”

The convention fixed a president’s term at four years, but, altering its previous arrangement, agreed that a president would be perpetually eligible for re-election. A president chosen by Congress, Mason had earlier reasoned, should be restricted to only one term in order to eliminate the “temptation on the part of the Executive to intrigue with the Legislature for a re-appointment.” But once the choice was removed from the legislature, that objection ceased to be relevant.

Article II begins, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” The sentence seems innocuous, merely descriptive. But it contrasts starkly with a companion sentence in Article I: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” Is the absence of the restriction “herein granted” in Article II merely chance phrasing? No matter, for presidents have seized upon this phrasing to claim powers not enumerated in the Constitution. They have issued proclamations, acted in emergencies without seeking Congressional approval, and entered into executive agreements with foreign nations. In the first century of the republic, executive agreements were nearly as frequent as treaties, and in the next half-century they outnumbered treaties by almost 2–1.

Article II further provides that “he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” another innocent-sounding clause pregnant with potential for amplifying the presidential realm.

Perhaps not guilelessly, the committee fashioning Article II created, as the political scientist E. S. Corwin later noted, “the most loosely drawn chapter of the Constitution.” He added: “To those who think that a constitution ought to settle everything beforehand, it should be a nightmare; by the same token, to those who think that constitution makers ought to leave considerable leeway for the future play of political forces, it should be a vision realized.”

Similarly, the British historian Marcus Cunliffe later remarked, “Napoleon once said that constitutions should be ‘short and obscure.’ . . . Much in the Constitution was vague, either because the delegates covered up disagreement with . . . words open to multiple interpretation, or because they were not able to anticipate the vast range of difficulties that would arise when the Constitution was tested.”

To the dismay of opponents of concentrated authority such as Mason, the Framers had also bestowed plenary powers on the president. When Charles Pinckney III expressed disappointment at “the contemptible weakness and dependence of the executive,” Mason gasped. Advocates of an energetic executive, though, applauded the empowerment.

“The duration of our president,” said John Adams, “is neither perpetual nor for life; it is only for four years; but his power during those four years is much greater than that of an avoyer, a consul, a podesta, a doge, a stadtholder, nay, than a king of Poland; nay, than a king of Sparta.”

Unlike Congress, which, for months at a time, would be adjourned, the president would hold sway throughout the year. Subsequently, a congressman inquired: “Is anything more plain than that the President, above all the officers of Government, both from the manner of his appointment, and the nature of his duties, is truly and justly denominated the man of the people? Is there any other person who represents so many of them as the President?”