Our nation came to be thanks to an unexpected explosion of political talent in an emerging nation on the fringe of the Atlantic world.

-

November/December 2025

Volume70Issue5

Editor’s Note: Joseph Ellis is the author of numerous books on the Founding Era and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History and the National Book Award, among other honors. Portions of the following essay appeared in his book, American Dialogue: The Founders and Us, which explores the relevance of the views of the Founders to issues in America today.

The British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once observed that there were only two occasions in the history of Western civilization when the political leadership of an emerging nation behaved as well as anyone could reasonably expect. The first was Rome under Caesar Augustus; the second was the United States under that collection of characters called the founders.

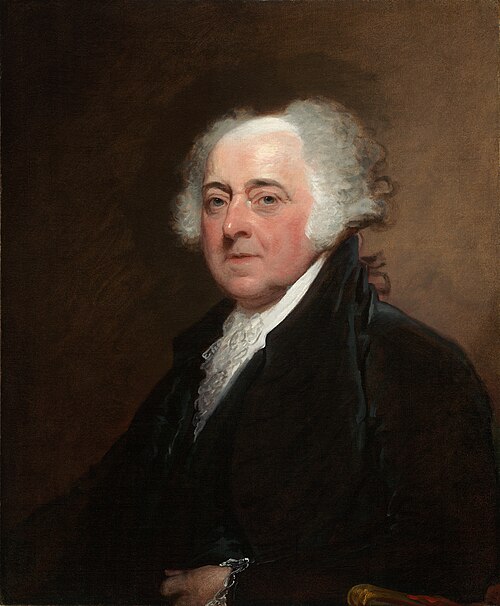

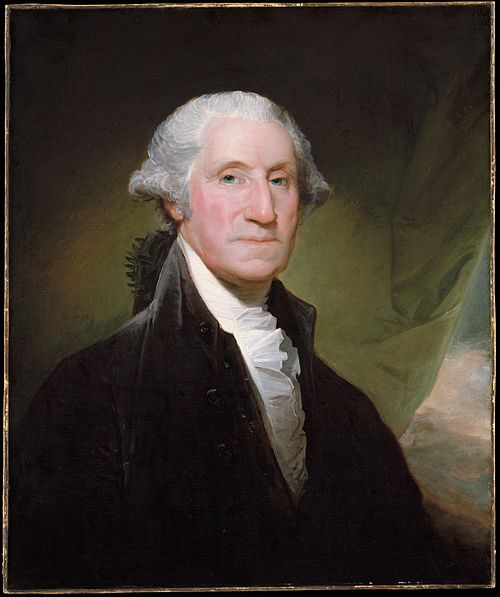

The clear consensus among scholars is that the political leadership that emerged in the last quarter of the eighteenth century displayed more creative talent than any subsequent generation of American statesmen. Polls of historians and political scientists routinely rank Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt ahead of George Washington on the list of great American presidents, but the range of political creativity surrounding Washington, chiefly Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, and Hamilton, has no serious competitor as a gallery of greats.

How to account for this unexpected explosion of political talent in an emerging nation on the fringe of the Atlantic world is a question that has attracted multiple explanations, both at the time and ever since. Over fifty years ago the historian Douglass Adair put the question most mischievously. The white population of Virginia in 1790 totaled about 400,000 souls, Adair noted, which was slightly smaller than the current population of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. If we conducted a rigorous survey of the residents of Wilkes-Barre, could we expect to find the likes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Patrick Henry, George Mason, and John Marshall? Obviously not.

Such juxtapositions, the historical equivalent of shooting fish in a barrel, should be avoided at the start, since it ends the conversation about leadership before it can begin. Similarly, one explanation for the singular status of the founding generation needs to be ruled inadmissible: there can be no reference to divine intervention. Soon after their departure, a thick cloud of incense formed around the founders that required over a century to dissipate. But it is still fashionable for some wholly secular historians to use words like miracle, sacred, and godlike to describe the achievement of the revolutionary generation.

Such lingering vestiges of religiosity corrupt any serious inquiry into the sources of their creativity. The founders desperately wanted to be remembered. But they must not be canonized.

What, then, did these fully flawed patriarchs achieve? With the advantages of hindsight, we can say they made three major contributions to modern political thought of enduring significance. They also failed to resolve two deep-rooted problems that, in the end, must be listed as tragedies.

On the triumph side of the ledger, they created the first nation-size republic. It was previously presumed that republican governments based on popular consent could function only in small areas like Swiss cantons or Greek city-states, because republics were supposedly incapable of imposing authority over a large and far-flung population. This is what Lincoln meant during the Civil War when he described the conflict as the acid test of whether “any government so conceived and so dedicated can long endure.” Over two centuries since its founding, the American republic has endured, in the process becoming the model for the liberal state in the modern era. There were, in effect, two foundings: winning a war for independence and creating a largescale republic. The two achievements taken together are what make the American Revolution a revolution.

Second, they created the first wholly secular state. Before the American founding, it was assumed that state support for an established religion was a mandatory feature of all viable governments, because it enforced a consensus on the common values that made a collective sense of purpose possible. While many of the states retained various Protestant establishments well into the nineteenth century, the founders insisted on a complete separation of church and state at the national level, thereby overturning the long-standing presumption that only shared religious convictions could hold a nation together.

Third, they rejected the conventional wisdom, agreed upon since Aristotle, that political sovereignty was by definition singular and indivisible and must reside in one agreed-upon location. The Constitution defied this assumption by creating multiple and overlapping sources of authority in which the blurring of jurisdiction between federal and state levels, as well as between and among branches of government, became an asset rather than a liability. The very idea of sovereignty became problematic, and its rhetorical depository, “the people,” an inherently elusive location.

The two conspicuous failures of the revolutionary generation involved Native Americans and African Americans, more specifically the inability to avoid Indian removal, a covert form of genocide, and the failure to put slavery on the road to extinction before it necessitated the bloodiest war in American history to end it. The fact that these failures were tragedies is beyond debate. The more difficult question is whether they are best understood as Greek or Shakespearean tragedies, meaning inherently unsolvable for reasons beyond human control or susceptible to solution with the right kind of political leadership.

By my lights, the Native American dilemma was a Greek tragedy, in the sense that the problem became intractable and unsolvable once the demographic wave of white settlers began flowing across the Alleghenies after the United States acquired the eastern third of the North American continent in the Treaty of Paris (1783). Washington devoted his fullest energies to the creation of a series of Native American homelands east of the Mississippi, which would have avoided Indian removal and provided a framework for the just resolution of what was clearly a moral problem in the fullest meaning of that term. But the combination of demography and democracy overwhelmed Washington’s most focused and strenuous leadership, suggesting that once the torrent of white settlers began pouring into Indian country, nothing could have altered the outcome.

As already noted, slavery is the original sin of American history, and if it is made the ultimate test of leadership for the revolutionary generation, then the founders failed the test. This is not just a tragedy but America’s defining tragedy. And the only question is whether it belongs in the Greek or Shakespearean category. Was there any way to end slavery short of war?

In framing that debate, the following facts must be faced squarely. All the prominent founders, including southern slave owners, recognized that slavery contradicted the core values of the American Revolution. Most of the founders thought that the window of opportunity to end slavery was opening – that it would die a natural death if isolated in the Deep South, because slave labor could not compete with free labor, a misreading of history rooted in a failure to foresee the emergence of the Cotton Kingdom. Any effort to put slavery on the road to extinction during the Constitutional Convention would have rendered the ratification of the Constitution impossible, leaving the southern states free to extend the slave trade indefinitely and silence all criticism of slavery itself. And last and most worrisome, although the founders were capable of imagining a nation-size republic and a secular state, they were incapable of imagining a biracial society, which meant that any emancipation scheme bore the enormous burden of transporting the free black population to some distant location outside the nation’s borders.

The problem became intractable after 1820, when the Missouri Compromise allowed for slavery’s expansion and cotton production became the mainstay of the southern economy. At that point slavery became a Greek tragedy. Before that date, however, the window of opportunity to end slavery was still open. (Washington thought a full-scale debate should begin after the slave trade ended in 1808.) But no one stepped forward at the national level to provide the kind of leadership on slavery that Washington had attempted to provide on the Native American question. In the wake of the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson was perfectly positioned to play that role; and all the political and economic ingredients were present to enact a gradual emancipation plan that included removal of the emancipated slaves to the newly acquired western territories. This must be judged a failure of leadership in the Shakespearean mode, with racism the fatal flaw.

Slavery will forever remain the signature sin of the founding. Any historical interpretation that ignores or obscures that indisputable fact is unworthy of serious consideration. Facing it, however, must not be allowed to end the argument about the leadership legacy of the founders. The whole point about the founding, which defies any wholly moralistic agenda, is that the triumphs and tragedies coexisted, indeed were mutually dependent. The moral imperative to end slavery had to compete with the political imperative to win the war against Great Britain and then create a national government, both goals that required the inclusion of slaveholding states. Within the constraints imposed by that intractable reality, the founders managed to maximize the creative possibilities of their time more fully than any subsequent generation of political leaders in American history. The salient question is how they did it.

One answer, which came from the revolutionary generation itself, is sprinkled throughout the letters of several founders. The clearest articulation of this “crisis” explanation appeared in David Ramsay’s History of the American Revolution (1789): “The Revolution called forth many virtues and gave occasion for the display of abilities which, but for that event, would have been lost to the world. In the years 1775 and 1776, the country being suddenly thrown into a situation that needed the ability of all its sons, a vast expansion of the human mind speedily followed. It seemed that the war not only required but created talents.”

Washington made the same argument to explain the improbable passage and ratification of the Constitution. The very hopelessness of the task, and the strength of the opposition, he observed, “had called forth abilities which would otherwise not perhaps been exerted that have thrown new lights on the science of Government [i.e., the Federalist papers], that have given the rights of man a full and fair discussion.”

This explanation anticipated the argument of Arnold Toynbee in A Study of History (abridged edition, 1954) that leadership appears only in societies undergoing great crises. Although historians of the Civil War might contest the claim, the American Revolution is arguably the greatest political crisis in American history. If it had failed, Washington would have remained an inconsequential Virginia squire, Adams an obscure country lawyer. This crisis explanation also reminds us that Jefferson’s felicitous words in the Declaration, “our lives, our fortune, and our sacred honor,” were an accurate description of the allor-nothing risk the leaders of the movement for independence were required to run. Once committed to “The Cause,” leadership became the only option forward; there was no turning back.

Another explanation that amplifies the crisis argument comes from Douglass Adair in an essay entitled “Fame and the Founding Fathers” (1966). As the title suggests, all the prominent founders were obsessed with living on in the memory of subsequent generations. Adams is most articulate about this quest for secular immortality, which he acknowledged was an irrational impulse, but the collected writings of all the founders are so voluminous in large part because they preserved their letters for our subsequent scrutiny. Similarly, those iconic portraits by John Trumbull and Gilbert Stuart show us men who were posing for posterity.

Adair called attention to the fact that the revolutionary generation came of age at a moment in Western history when the prospect of everlasting life in a Christian version of the hereafter was becoming problematic, so that living on in the memory of succeeding generations became the only assured afterlife. The election that counted most for the founders was posterity’s judgment, and they chose to win that vote by conducting themselves according to a classical code that linked their personal ambitions to the larger agenda of nation-making. They were, in effect, on their best behavior because they knew we would be watching. (Washington’s decision to free his slaves in his will, for example, was motivated by his realization that failure to do so would forever stain his reputation.) The crisis explanation helps us understand why a political elite emerged when it did. Adair’s focus on fame helps explain the distinctively classical character of leadership the founders consciously strove to imitate.

Gordon Wood provides another angle from which to view the leadership question. He describes the revolutionary era as a truly special moment that afforded opportunities for political leadership and creativity never possible before and never achievable since. It was, Wood argues, simultaneously a post-aristocratic and pre-democratic age. On the one hand, this meant that politics was open to a whole class of talented men (women were still unimaginable as leaders outside the family) who would have languished in obscurity in Europe or Great Britain because they lacked the proper bloodlines. There was still a discernible social hierarchy in America, but compared to all other advanced societies at that time, the United States afforded an unprecedented opportunity for movement from bottom to top. As a result, when the revolutionary crisis arrived, it could draw upon the latent talent from a segment of the population never before allowed access.

On the other hand, the founders were a self-conscious elite, what Jefferson called a “natural aristocracy” based on merit rather than blood. They were therefore immune to democratic mythology about the innate wisdom of the common man, completely comfortable with their own superiority. All of the first five presidents regarded the act of campaigning for office as a confession that they were not statesmen but demagogues. While popular opinion was hardly irrelevant, it was regarded as flighty, shortsighted, and easily manipulated. The ultimate allegiance of the founders was not to “the people” but to “the public,” which was the long-term interest of the citizenry that they, the founders, were obligated to serve regardless of the short-term political consequences. During his retirement, for example, Adams boasted that his greatest achievement as president was to lose the election of 1800, because his defeat was a direct consequence of his unpopular but historically correct decision to avoid war with France.

By straddling these two worlds, without belonging completely to either one, the founders maximized the leadership potential of both. The founders were America’s first Lost Generation, for the moment they occupied can never come again. As Wood is at pains to show, all of the founders who lived long enough to witness the emergence of a full-blooded democratic political culture in the 1820s regarded it as an alien presence and not at all what they had in mind when they launched the American experiment in 1776. While there is much to admire in the founders, the distinctive brand of leadership they provided is impossible to duplicate because — and this is deeply ironic — we inhabit a democratic America that they made possible but that then made them impossible.

A slightly different interpretive angle on the special character of the revolutionary generation comes from Bernard Bailyn, who focuses on the distinctive geographic location of the founders. As already noted, Washington identified the isolation of the North American continent and the enormous trust fund provided by the acquisition of a western empire east of the Mississippi as priceless assets that afforded the founders leadership opportunities denied to previous nation-builders. Bailyn is more interested in the location of the founders on the periphery of the British Empire, perhaps the last place one should expect to find an explosion of political creativity that changed forever the way we think about government. Bailyn poses the question for dramatic effect: How could this backwoods population of 3 to 5 million farmers, mechanics, and minor gentry, far removed from the epicenters of learning in London and Paris, somehow produce thinkers and ideas that fundamentally transformed the landscape of modern politics?

Bailyn’s answer is counterintuitive, that less was more. His earlier work on the Scottish Enlightenment prepared him to notice that being on the periphery in Edinburgh rather than the cosmopolitan center of London allowed Scottish thinkers like David Hume and Adam Smith to range more widely because their imaginations were not constrained by encrusted traditions, embedded institutions, and socially sanctioned inhibitions. Likewise for American thinkers like Adams, Madison, and Jefferson, the cultural stigma of being mere provincials turned out to be more of an asset than a liability, since they were free to question the old self-evident truths and invent their own without fear of offending established sources of authority because, in fact, there were none.

For instance, certain radical ideas, like divided sovereignty and separation of church and state, which were consigned to the fringes of British political thought, could and did enter the mainstream in the American context, where they were then sanctioned as cherished revolutionary principles. Like Wood, Bailyn emphasizes the distinctive historical conditions that shaped the achievement of the founding era, which makes it forever alluring and forever gone.

Finally, I have argued that the political achievement of the revolutionary generation was partially a function of its ideological and even temperamental diversity. We speak of the founders in the plural because the American founding was a collective enterprise. Yet the founders harbored different beliefs about what the American Revolution meant, as the Adams-Jefferson correspondence most fully exposes. This political and psychological diversity enhanced creativity by generating a dynamic chemistry that surfaced in the arguments that ensued whenever a major crisis materialized. Diversity made dialogue unavoidable.

If left alone, Jefferson would have carried the infant nation perilously close to anarchy. Hamilton would have erred on the side of autocracy. The collision of convictions not only enriched the intellectual ferment, it also replicated the checks and balances embedded in the Constitution with a human version of the same balancing principle. Because the face of the American founding was, and still is, a group portrait, our depiction of the revolutionary generation has never developed into a one-man despotism in the Napoleonic mode, and the political legacy it bequeathed to posterity defied any one-dimensional definition.

As a result, the founders will forever resist exclusive ownership by any political party or ideological camp. To paraphrase Walt Whitman, the founders contained multitudes. The American Dialogue they framed is a never-ending argument that neither side can win conclusively. It is the argument itself, not the answer either liberals or conservatives provide, that is the abiding legacy.

Whether that legacy still speaks to us depends almost entirely on whether we are listening and willing to engage in argument.