Setting out 250 years ago this month, Henry Knox’s “Noble Train” carried 60 tons of desperately needed artillery to help patriots oust British forces from Boston.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

See our slideshow for more photographs of the current reenactment of the Knox expedition.

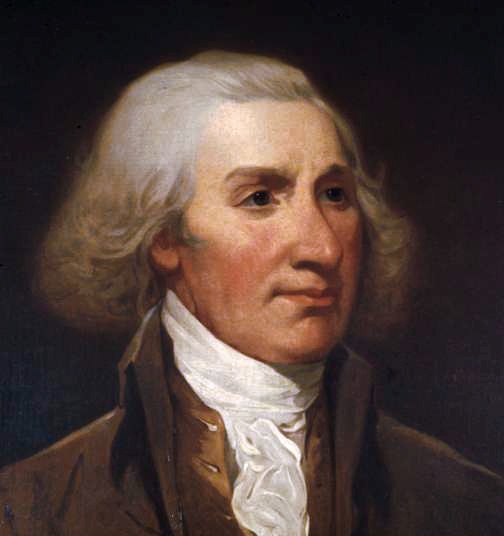

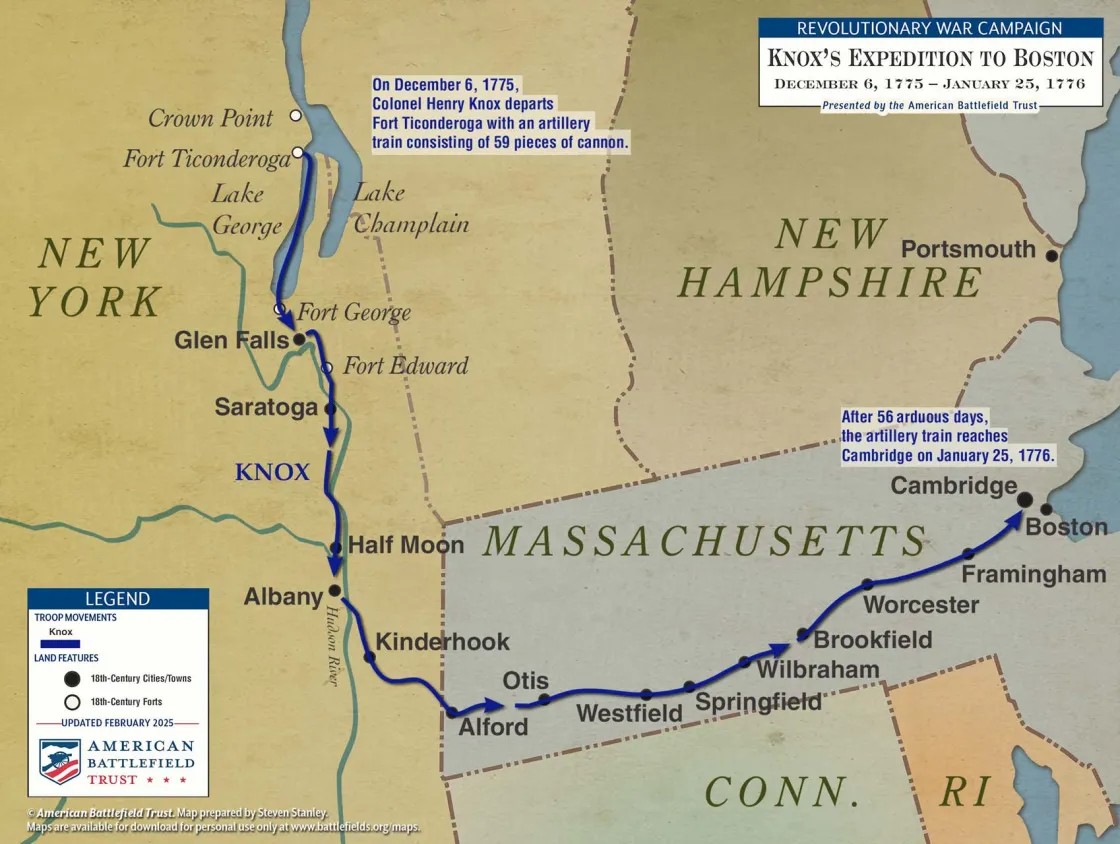

Two hundred and fifty years ago this month, a 26-year-old bookseller from Boston led a team of patriots that hauled 56 cannon and barrels of lead and flints 300 miles through the wilderness from Fort Ticonderoga in northern New York to the American forces besieging Boston. Henry Knox and his men accomplished that feat in the middle of winter, hauling 60 tons of supplies on ox carts and sleds up and down the Berkshire mountains in snowstorms and bitter cold.

“Henry Knox’s expedition to secure cannon from Ticonderoga remains one of the most compelling experiences from the Revolutionary War,” says Matthew Keagle, curator of Fort Ticonderoga. “It’s a classic American story of someone from a humble upbringing who finds his way to greatness through his skills, his merit, and his experience.”

Washington Irving described Knox as “one of those providential characters which spring up in emergencies as if formed by and for the occasion.”

Earlier in 1775, just weeks after the fights at Concord and Lexington on April 19, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety commissioned Benedict Arnold to try to capture the cache of weapons at Ticonderoga. Separately, leaders in Connecticut encouraged Ethan Allen to try to take the fort with his Green Mountain Boys, a militia group from the area that would later become Vermont. Although the two groups acted independently, they would join forces before attacking the fort.

Ticonderoga was a large star-shaped fortress on Lake Champlain in northern New York that had been built in the 1750s by the French, who called it Fort Carillon. The stronghold controlled the waterways that facilitated north-south travel between Canada and New York, but by 1775, Ticonderoga was manned by only a small garrison of British troops. When Arnold and Allen arrived at its gate before dawn on May 10, they surprised the garrison, who weren’t even aware hostilities had broken out.

The British surrendered without a shot fired, giving American patriots their first victory of the Revolutionary War. Four days later, the Green Mountain Boys captured Crown Point, a smaller but strategic fortress 16 miles north of Ticonderoga

On May 26, Arnold wrote to officials in Massachusetts that he had captured some British vessels and started to accumulate mortars and howitzers to send to Boston. He also noted that he had four gins, which were large tripods used for lifting cannon into a cart or gun carriage. But the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, focused on challenges with the British army in their midst, decided to let Connecticut take charge of the work at Ticonderoga.

At that time, the colonies had separate military forces, meaning that Benedict Arnold would no longer be in command since he fought for Massachusetts. So he resigned. The effort to gather cannon slowed down.

The following month, Congress appointed Philip Schuyler, a wealthy veteran of the French & Indian War, to command the Continental Army’s Northern Department. George Washington sent him orders on June 25, 1775, to ensure the forts on Lake Champlain were provisioned with food and ammunition, monitor the situation with the various Indian tribes, and report on forces, stores, and intelligence. He was also instructed to plan and organize an expedition to take Canada. Schuyler soon left to inspect the garrisons.

When George Washington arrived in Boston and took command on July 3, 1775, he found there were only 36 barrels of gunpowder, barely enough for about seven rounds per soldier. At the time, most gunpowder and armaments had to be imported from Europe, and the American shortage was critical. He would look to Ticonderoga for help. The British had retreated to quarters in Boston after the disastrous fight at Bunker Hill, and were supplied and protected by a dozen Royal Navy warships in the harbor. There was little Washington could do to change the situation, despite having nearly 12,000 men who had converged from all over New England and now largely surrounded the city.

Gen. Schuyler discovered he had much work to do to get his forces in shape. Arriving at a camp manned by Connecticut forces at the northern end of Lake George, he hailed the guard and was shocked to discover the man was “embraced in the downy arms of sleep.” The rest of the garrison was no better. “Another guard, equally with the first, felt the power of the god of sleep,” Schuyler later wrote. He claimed he could have run his bayonet through every man of the guard and burned the boats they were building before anyone would notice.

Meanwhile, in Boston, General Washington was increasingly desperate for artillery. After several months in command, he had made little progress. The Americans surrounded the British forces who had withdrawn into the city, but could inflict little damage to their fortifications or ships.

In October, a delegation arrived from Congress alongside officials from Massachusetts and Connecticut to discuss issues facing the Continental Army. The foremost concern was where to get cannon. Earlier that summer, Washington had received a survey of artillery in the American lines from his chief engineer, Richard Gridley, who confirmed they were woefully short of what was needed to break the siege.

“While Americans could, at times, muster sufficient men, they often lacked the equipment, the guns, the gunpowder, the cannon, to conduct the war,” says Matthew Keagle. “It was the logistical end of things that was more challenging.”

On November 16, 1775, Washington issued orders to a young volunteer, Henry Knox, to travel to Ticonderoga by way of New York City to see what spare munitions might be available for transport back to Boston. “The want of them is so great, that no trouble or expence [sic] must be spared to obtain them,” wrote Washington. If there was little available in New York, Knox was to “Get the remainder from Ticonderoga, Crown point, or St Johns — if it should be necessary, from Quebec, if in our hands.” Washington knew that the expedition of American forces into Canada was underway, and hoped they might gain some materiel for Boston.

Not only did the Americans lack artillery at the time, but few in the army had been trained in building fortifications or handling cannon. In past conflicts in America, those tasks were handled by British officers.

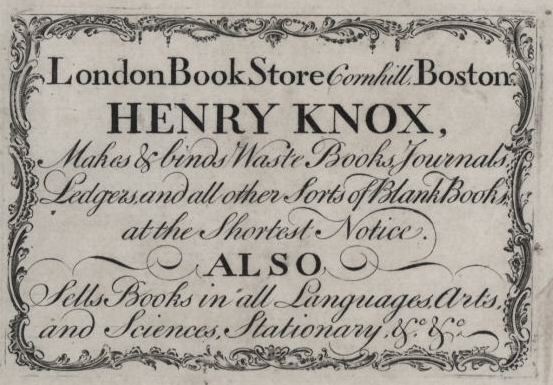

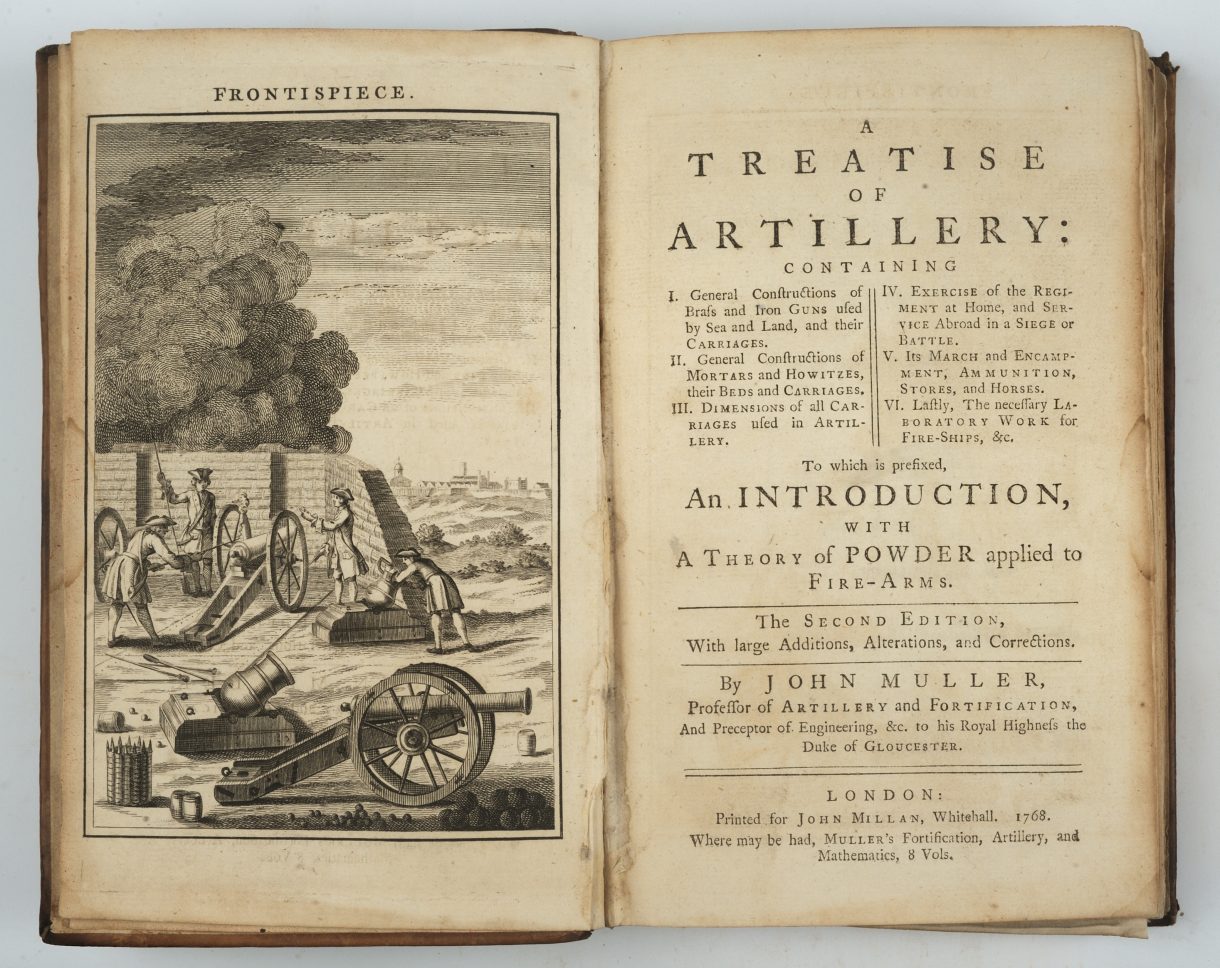

Although Knox had no military experience, he had sold books on military subjects in his bookstore and read them avidly. Works such as A Treatise on Artillery by John Mueller, the most influential English book on artillery, provided instruction on the fabrication of artillery and handling of guns, particularly their use in the field. J.C. Lydell’s An Essay on Field Fortification was a practical guide that showed “how to trace out on the ground, and construct in the easiest manner, all sorts of redouts and other field works.”

Knox also procured numerous French, German, and Dutch books on artillery, including the famous volume on systems of fortification by Sébastien Le Comte de Vauban, which had influenced the design of so many forts around the world, including that of Fort Ticonderoga.

General Washington gave Knox a broad mandate and £1,000 to pay for personnel and supplies. The 26-year-old officer, now promoted to colonel, set off a few days later charged with accomplishing a feat that few people thought possible. Washington also wrote to Schuyler, instructing him to do everything possible to assist the effort.

Knox traveled first to New York City, but found few armaments available, since whatever they had was needed to defend the city. He left on the 27th, noting in his diary, “glad to leave N York it being very expensive.” The young officer then traveled up the Hudson to Albany and overland to Lake George and Ticonderoga.

Arriving at the fort on December 5, 1775, Knox discovered that much work had already been done by the men of the Northern Department who had brought together cannon captured at former British forts, including Crown Point on Lake Champlain, and Chambly and St. Jean on the Richelieu River across the Canadian border. Those weapons were added to the ordinance already at Ticonderoga.

Knox selected the artillery that would be most useful in Boston and supervised as the men packed up 43 cannon, including one nicknamed “Old Sow” that weighed more than 5,000 pounds and could throw a 24-pound ball, as well as 14 mortars and two howitzers. Two 12-inch mortars made in France would be able to rain down massive explosive shells on the British army. There were also several cohorns (or coehorns), which were small, portable mortars that could fire explosive shells at high angles to hit targets behind walls or trenches, making them helpful during sieges or against ships.

It was remarkable that so much work had already been done that Knox needed only four days at the fort. “When we think about the Knox expedition, we often think about Henry Knox alone,” notes Matthew Keagle. “But the documents in our collection at Fort Ticonderoga make it clear that Knox didn’t work alone. It was a whole cast of Americans that helped accomplish what is arguably the most important logistical feat of the Revolutionary War.”

By December 9, the 59 cannon had been dragged and hauled by ox cart to the north end of Lake George and loaded onto boats to begin the journey south down the lake.

It took eight days to ferry the cannon 32 miles down the nearly frozen lake to the town of Lake George. One day, “the wind sprung up very fresh & directly against us,” Knox recorded in his diary. “The men after rowing exceedingly hard for above four hours seem’d desirous of going ashore, to make a fire to warm themselves.”

Later Knox recorded that a scow loaded with cannon “had run on a sunken rock” and the men “had broken all the ropes which they had in indevoring to rouse her off.” Eventually they were able to free the boat with more rope from Ticonderoga and head south, reaching Fort George by December 17.

That day the young officer reported his progress to General Washington and commented on the challenges: “It is not easy [to] conceive the difficulties we have had in getting them here over the Lake owing to the advanc’d Season of the Year & contrary winds, but the danger is now past; three days ago it was very uncertain whether we could have gotten them untill next spring, but now please God they must go.”

Knox struck an optimistic tone. “I have had made forty two exceeding Strong Sleds & have provided eighty Yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield,” he reported. “I hope in 16 or 17 days time to be able to present to your Excellency a noble train of artillery.”

The schedule would prove unrealistic, but Knox's phrase “Noble Train of Artillery” would become time-honored in the new nation.

The expedition faced many more problems as they hauled the cannon overland sixty miles to Glen Falls, Saratoga, and then Albany, crossing the frozen Hudson River four times. Knox journeyed out ahead to check the route and ran into a deadly blizzard that forced him to “undertake a very fatiguing march of about 2 miles in snow three feet deep thro’ the woods there being no beaten path.” He “almost perish’d with the Cold.”

At Albany on December 29, Knox recorded in his diary that the snow was “too deep for the Cannon to set out even if the Sleds were ready… These inevitable delays pain Me exceedingly.” But happily General Schuyler had “sent out his Waggen Master & other people to all parts of the County” and rounded up 124 pairs of horses.

Leaving Albany, the Noble Train headed for Kinderhook, New York, and then east across the Berkshires to Alford, Otis, and Springfield, Massachusetts. They reached Framingham around January 24, 1776, and Knox himself arrived in Cambridge three days later to report to General Washington personally.

Earlier, Knox had reminded Washington that he was bringing mostly just the tubes or barrels of guns. “There are no carriages nor Implements to the Cannon nor beds to the Mortars, all of which must be made in Camp,” he had noted. Over the next weeks, the cannon remained in Framingham while carpenters and blacksmiths built new carriages for the guns, including wheels, axles, stocks, and cheeks.

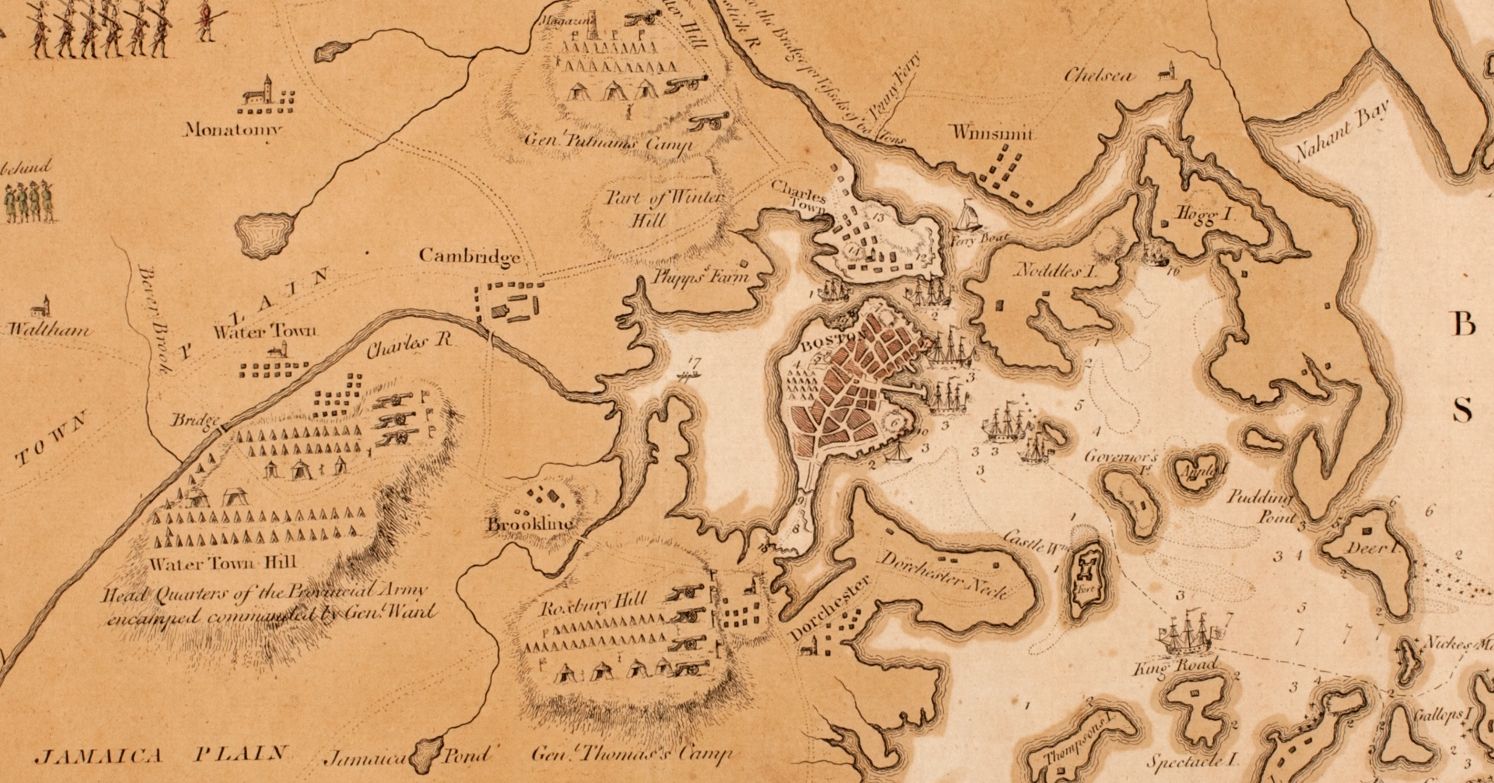

In a meeting on February 16, 1776, Washington’s war council debated about how to proceed against the British. Their forces surrounded the city, with Gen. Putnam’s camp to the north near Cambridge, Gen. John Thomas to the south, and the main camp to the west. A direct assault on the British garrison could be costly, but if the new cannon could be deployed on Dorchester Heights to the southeast of Boston, they could fire at both the city and the ships in the harbor.

A few days before, a small British force had marched up Dorchester Heights to look into fortifying the site, but found it would be difficult with the frozen ground. The officer in charge reported that they “took 6 Rebel prisoners, burnt 6 or 8 Empty uninhabited houses and barns, and return’d about ½ after 6 o’clock.”

Washington and his generals agreed to try to fortify the Heights. Any move would have to be done swiftly and secretly to avoid being contested by the British.

Washington ordered a distraction to cover the movement. On the nights of March 2, 3, and 4, a large bombardment of the city from Cobble Hill, Cambridge, and Roxbury using some of the artillery brought by Knox diverted the attention of British forces to the west of town. Then, on the night of March 4, 1776, General John Thomas and Colonel Gridley led 1,200 soldiers with 300 oxcarts to transport tools and materials up Dorchester Heights to fortify it as stealthily as possible.

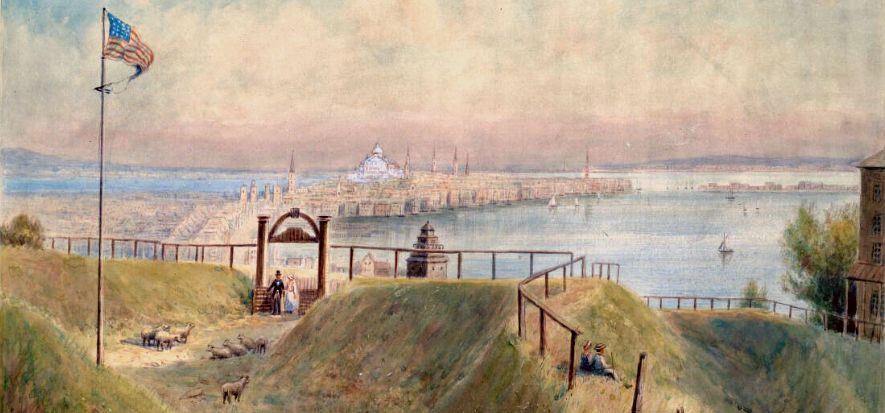

When dawn broke on March 5, 1776 — the 6-year anniversary of the Boston Massacre — everyone could see what the Continental forces had achieved. A fortification with cannon now towered over Boston and the ships in its harbor.

“My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months,” British General William Howe complained. He planned an attack on Dorchester Heights in response, but a storm prevented immediate action. Surrounded by Washington’s army, Howe recognized he was at a military disadvantage and decided to remove his troops from the city.

The next day, Howe gave the order to prepare for evacuation. On March 17, 120 ships carried 9,000 British soldiers, 1,200 dependents, and 1,100 Loyalists out of Boston.

Henry Knox’s “Noble Train” of artillery had proven to be the decisive factor.

It was “the most significant logistical accomplishment of the Revolutionary War,” sums up historian Archer O'Reilly III. “It freed Massachusetts, embarrassed the primary British command in the colonies, secured Washington’s reputation, emboldened the patriots, and pushed fence-sitters in Congress and other colonies towards the cause of Liberty.”