Paper ballots were meant to protect the voter from intimidation, but they offered the ward heeler and the canny party boss ereat possibilities for mischief

-

September 1992

Volume43Issue5

“I’ve got a ballot, a magic little ballot,” sang supporters of Henry Wallace’s presidential campaign in 1948. ”… There is magic in that ballot when you vo-o-o-ote !”

Americans performed magic with their paper ballots for a long time. In fact, Massachusetts Puritans were electing governors by written ballots as early as 1634, influenced perhaps by city elections they had witnessed in the Netherlands. Most early voting, however, remained viva voce: in person and out loud. It was a very public act. Virginia electors announced their choices in the presence of the rival candidates, usually gaining an “imbibable” from the one they favored. When the printed ballot (locally called a prox) emerged in Rhode Island by 1744, its purpose was not secrecy but the convenience of voters unable to journey to Newport for election day.

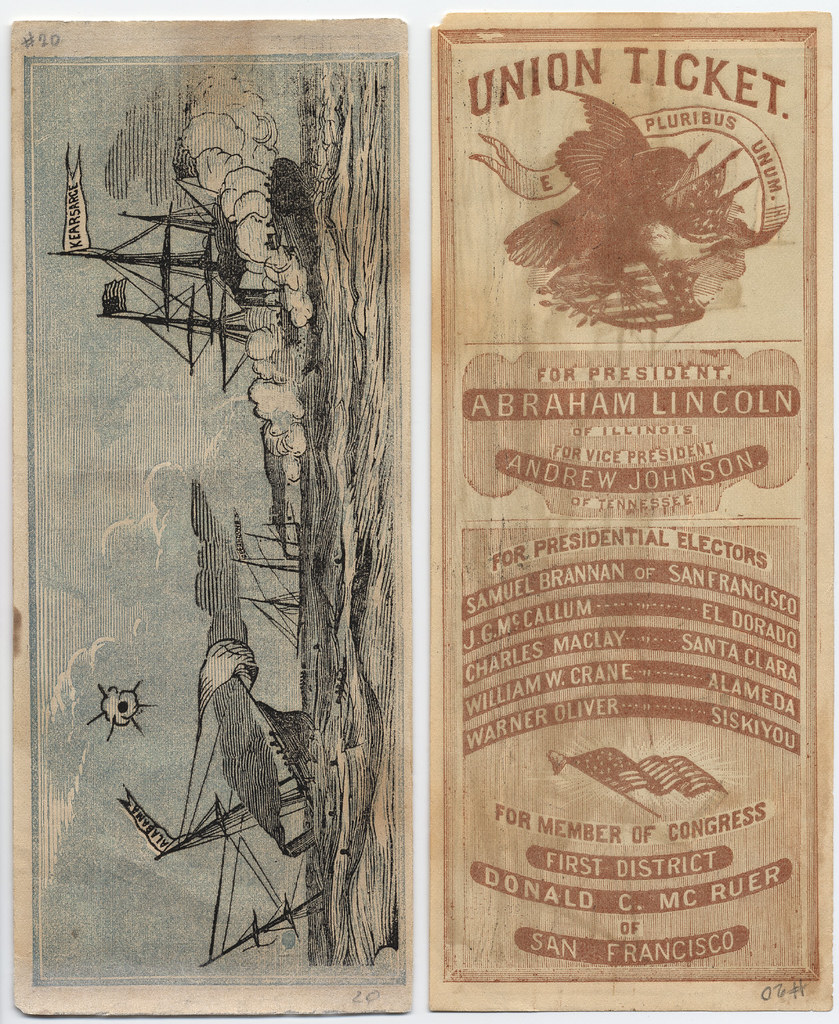

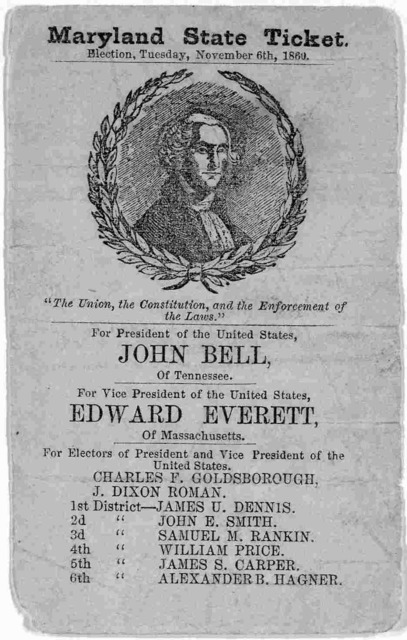

Long before the Revolution, ballots had evolved into the form we recognize today: a party’s candidates were listed from top to bottom in order of importance, from governor down to coroner. To lure voters, printers adorned their ballots with handsome ornaments and sometimes with a little propaganda. “Liberty, Property, & No Stamps,” reads a 1766 prox; in the next year a ballot tagged “Supporters of the Colony’s Plights” vied with one aimed at “Seekers of Peace.”

Viva voce remained the dominant mode of voting until the 1820s, when the growth of cities and the gradual extension of suffrage beyond prominent men of notoriety made change essential. Jeffersonians hoped that the paper ballot would constitute a secret vote that workmen might cast free of intimidation by their wealthy employers, but this wasn’t always the case. Some localities required separate ballot boxes for each party; others made voters sign their ballots.

As more and more offices became elective, ballots stretched longer; some grew so unwieldy that they had to be cut into national, state, and local segments. Modestly declining to vote for himself in 1860, Abraham Lincoln snipped off the national part at the top and voted only the state and local Illinois Republican slates.

Ballots acquired more elaborate graphics and propaganda during the nineteenth century, incorporating easily recognizable symbols of hot political issues or humorous vignettes. To accommodate illiterate voters, the ballots brandished familiar party emblems and portraits of the candidates. Maryland Democrats overworked a steadily deteriorating “Jackson and Liberty” woodcut for half a century; as a result some German-speaking farmers are said to have thought they were voting for Old Hickory many years after his death.

Such confusion wasn’t always accidental, for ward heelers found the paper ballot ideal for dirty tricks. The stratagem of printing bogus opposition ballots that were deliberately flawed so as to be thrown out had been perfected by 1764. In 1828 posters warned “Jackson men” to “ Look out for the SPURIOUS TICKET . … If you vote that Ticket, your Vote is lost to the Good Cause.” In 1864 the national party chairman, August Belmont, was handed an apparently Democratic ballot only to discover the name of a Republican presidential elector in place of his own.

Ballots marked distinctively enough to be recognizable at a distance allowed both vote buying and voter intimidation. In the 1850s the Know-Nothing party dominated Baltimore elections by stationing crowds of awl-wielding thugs—the famous plug-uglies—around the ballot box. They chased off bearers of opposition tickets while stepping aside with cries of “Make way for the voters!” when their own supporters approached. While the large ballots favored in Boston and California made it hard to “stuff the ballot box,” they also rendered secrecy impossible. In contrast, tiny tissue-paper ballots used by South Carolina Democrats in 1880 were so readily concealed that a dexterous voter might slip in several at once.

The height of political prestidigitation was to make ballots simply disappear. Allowed to vote absentee, Civil War troops from Democratic southern Ohio were recorded as supporting Lincoln’s re-election by huge majorities. Eighty years later the historian William B. Hesseltine found their ballots in the files of the Ohio Historical Society still neatly sealed in their envelopes, forever uncounted.

Some reformers pressed for state-supplied envelopes to enclose the ballots, and in Maine an 1831 law prescribed uniform paper and ink. The corrupt excesses of the Gilded Age drove Thomas J. Durant, an eminent Washington, D.C., lawyer, to propose the universal adoption of the write-in ballot in 1872. while a year later Henry C. Marston tried to promote his “Patent Safety Ballot-Box.” Nothing really changed.

Although Kentucky clung to viva voce voting into the 1890s, it was Louisville that in 1888 introduced the Australian ballot, named for the country that developed it in the 1850s. This government-supplied ballot, listing candidates of all parties, finally made truly secret voting a possibility. Massachusetts immediately adopted the format statewide. What really killed the partisan paper ballot, however, was the scandalous national election that November.Allowed to vote absentee, Civil War troops from Democratic southern Ohio were recorded as supporting Lincoln’s re-election by huge majorities.

Although winning a majority of the popular vote, the Democratic President Grover Cleveland was defeated for re-election by the loss of Indiana, where the national Republican treasurer was caught buying votes wholesale, in blocks of five. Famed for his integrity and now seemingly martyred by ballot abuses, “Grover the Good” touched a national nerve in 1889 when he endorsed the ballot-reform movement. By the next election, in 1892, thirty-eight states had adopted Australian ballots, and Cleveland was returned to the White House. By 1910 only Georgia and South Carolina still held to the old ways. The modern voting machine, introduced in 1892, further safeguarded the vote, but paper ballots continued to be used as late as the 1960 presidential election.

For the most part, electoral magic tricks went out of the old ballots a century ago; we value them today for their historical content, their handsome graphics, and their highly imaginative propaganda that conjure up America’s untamed political past.