The year was a watershed as Americans shifted from demanding their rights as Englishmen to fighting for independence from the Crown.

-

Winter 2026

Volume71Issue1

Editor’s Note: Edward J. Larson is s professor at Pepperdine University and the University of Georgia, where he has taught for twenty years. His many books include Summer for the Gods, winner of the 1998 Pulitzer Prize in History, and most recently Declaring Independence: Why 1776 Matters, in which portions of this essay appeared.

America’s year of independence, 1776, began with virtually all those living in Britain’s thirteen North American colonies content to remain under royal rule so long as they could enjoy the basic rights of British subjects. By year’s end, most Americans who had a position on the matter favored separation from Britain. Although it was a year of intense fighting, much that mattered in 1776 happened away from the front lines of combat. Deeds on the battlefield were punctuation for inspiring words of liberty written and spoken throughout the colonies. The full history of 1776 sheds light on what mattered to Americans then and the legacy it left thereafter.

The year did not see a fundamental change in the contours of the fight for freedom. The storied battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill occurred during the spring of 1775. In June 1775, the Second Continental Congress named George Washington to lead a newly formed American army composed of colonial militias that were besieging British forces in Boston, and it adopted the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms a month later. Even the American conception of liberty did not change in 1776.

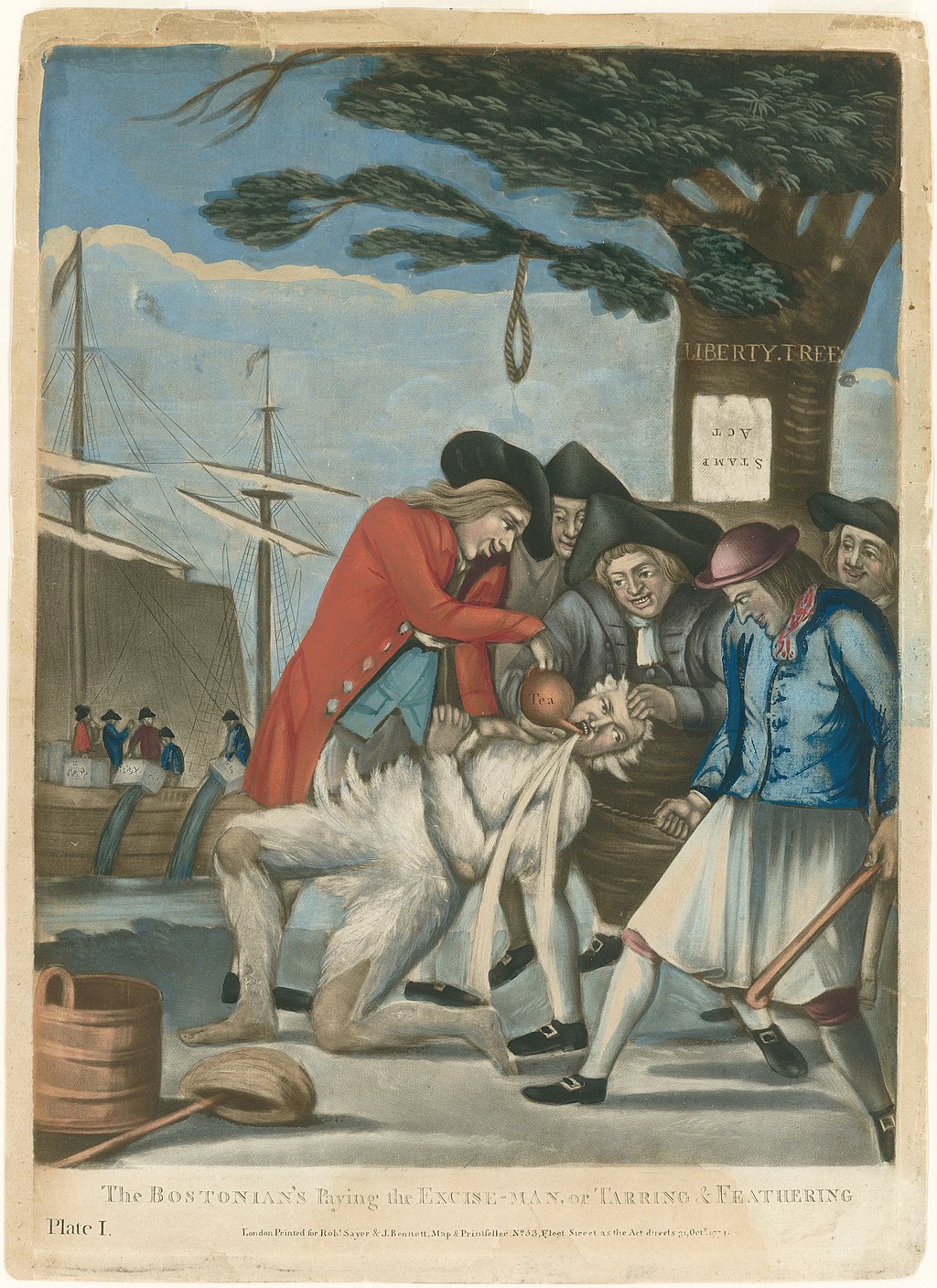

The individual rights declared in the state constitutions of 1776 echoed the Anglo-American rights demanded of Parliament in earlier petitions by the colonies and Congress. Slavery did not end in any state during 1776. Native Americans gained no legal rights, a woman’s status remained much the same, voting continued to be mainly the prerogative of property-owning males, and no state addressed economic inequalities.

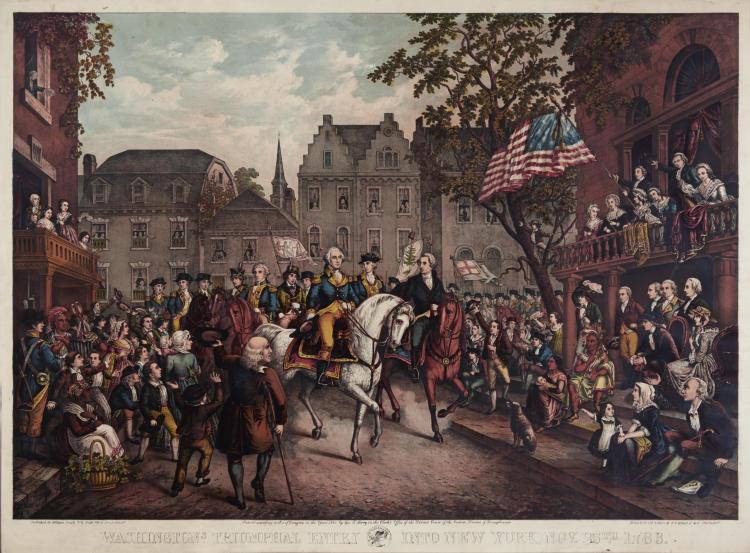

On the military front during 1776, the Americans drove the British from Boston and kept them out of Charleston, South Carolina, but lost New York City, Newport, and Canada. On balance, despite a small but inspiring year-end victory at Trenton, the Americans ended the 1776 military campaign in a weaker position than they began it. Defeat in the Battles of Long Island and Fort Washington left thou-sands of American prisoners of war in British prison hulks, and the remains of Washington’s army huddled in Morristown, New Jersey, while the British Army settled into winter quarters in New York City.

The fighting that occurred during 1776 mattered at the time mainly because it kept the Americans in the war, but battles fought at Saratoga and Yorktown in 1777 and 1781 brought American victory. What changed in 1776 was Americans’ embrace of independence as the foundation for their freedom and as the war’s goal. In 1776, a rebellion for liberty by subjects of British colonies became a revolution for independence by citizens of American states.

By focusing narrowly on the year’s battles and military strategy, many traditional accounts of 1776 have downplayed much that mattered. The best-selling book 1776 by David McCullough devoted only two pages to the Declaration of Independence and less to Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and the new state constitutions, yet these documents drove the fighting and helped to shape the future course of American history. They still matter.

Judged by their words and deeds, for Americans in 1776, “independence” meant separating from the British monarchy and establishing representative governments in the American states. Simply put, in the United States, “the people” would reign and their elected representatives would rule. The grievances that American colonists previously lodged against Parliament morphed into indictments against the king. Paine’s Common Sense, the first widely read pamphlet proposing American independence, presented this revolutionary concept in January 1776. Decrying absolutist governments as “the disgrace of human nature,” Paine called for representative ones with frequent elections to ensure “their fidelity to the Public will”.

In July 1776, Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration independence embraced the idea of representative government by stating at its outset that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The new state constitutions of 1776 institutionalized this idea, and North Carolina’s captured their collective spirit in its opening words: “All political power is vested in and derived from the people only.” Patriots in New York responded to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence by toppling a larger than life-size equestrian statue of King George III.

The revolutionary significance of American independence becomes apparent by comparing the governing authorities that preceded and followed it. The hereditary British monarchs asserted a divine right to reign over the American colonies and rule them through the exercise of their direct authority. Further, by the Declaratory Act of 1766, the British Parliament claimed “full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.” This Parliament had no American representatives. Its upper house consisted of hereditary and appointed lords. No one elected them. A highly restricted electorate that included less than one in ten adult British men and no women elected members of the lower house from grossly malapportioned districts.

Colonial governments in North America mirrored the British system. Not only did the king and Parliament rule over them, but with two exceptions the king or a proprietor in England named the colonial governors, who held broad powers. To create a colonial equivalent to the House of Lords, the governor or the king typically appointed members of the upper house of each colony’s legislature. A narrow electorate of property-owning men in each colony chose members of their respective lower houses.

Nothing in this system was democratic. In Common Sense, Paine depicted the British government as deeply authoritarian – ”The will of the king is as much the law of the land in Britain as in [absolutist] France,” he wrote. Similarly, because of King George’s treatment of his American subjects, the Declaration of Independence denounced him as a tyrant “unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

Equating independence with popular rule, Paine proposed having states governed by elected, single-house legislatures. While most of the new state constitution of 1776 did not go this far toward unchecked popular rule, they all organized every branch of state government to be elected directly or indirectly by the people. By doing so, they became models for free states everywhere.

Among the reforms of 1776, none mattered more than popular rule. Although voting made little difference in Britain, and many members of the House of Commons – including British generals William Howe and John Burgoyne – represented rotten boroughs run by their families, fair representation, free elections, and true vote counts mattered in the American states.

By replacing reigning monarchs and ruling lords with elected leaders, American independence gave impetus to the principle of equality under law. In Britain at the time, legal status and political office came from birth. While purportedly placing even the monarch under the law, England’s fabled Magna Carta conferred rights and power on the basis of rank, with more for barons, less for freemen, and still less for serfs. All were not created equal. Although some patriot leaders were wealthy and many held political posts before the American Revolution, none came from an ennobled or long-established family. Virtually all of them or their recent forebears earned their wealth and gained their positions in America, where economic and political opportunities existed for free white males.

In 1776, most Americans likely agreed with Paine’s statement in Common Sense that one honest man is worth more “to society and in the sight of God than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived” and readily accepted the self-evident truth of Jefferson’s historic phrase in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.” These became American norms.

Perhaps Jefferson and many other free white American men took this phrase as proclaiming their equal creation with those once thought their betters without applying to those they deemed beneath them, including enslaved Blacks and women. This could help explain why Jefferson freed only 10 of the more than 600 persons he held in bondage. In 1776, when the slaveholding states of Virginia and Delaware used similar words in their state constitutions, they qualified them to apply only to persons in society, which excluded Native Americans and enslaved Blacks. For northern states that used this phrase in their state constitutions without qualification, it prodded them toward ending slavery. When an enslaved Massachusetts woman known as Mum Bert first heard the phrase quoted from her state’s new constitution in 1780, she demanded and secured her freedom in court.

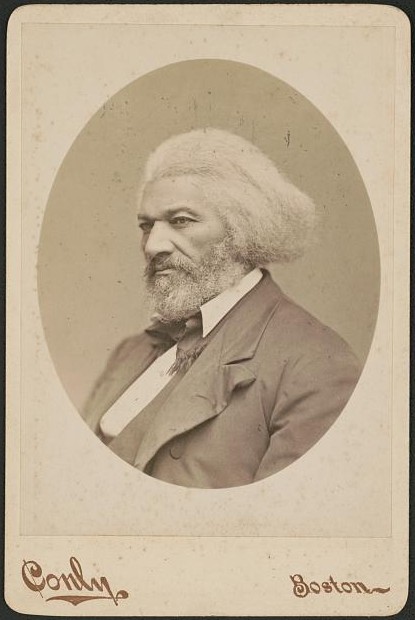

In the next century, opponents of slavery and advocates of women’s suffrage understood the Declaration’s assertions about human equality under law as foundational to the American identity. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton began her Declaration of Sentiments issued at Seneca Falls by paraphrasing the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal,” she declared. In his powerful 1852 speech decrying American slavery, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” Frederick Douglass nevertheless professed to draw “encouragement from ‘the Declaration of Independence,’ the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions.” Two years later, after Congress opened the door to slavery’s westward expansion through the much maligned Nebraska Act, Abraham Lincoln declared, “The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska are utter antagonisms.’’

Modern Americans drew inspiration from the ideals of 1776 as well. “In 1776 we waged war in behalf of the great principle that Government should derive its just powers from the consent of the governed,” Franklin D. Roosevelt told an anxious nation on the eve of World War II. “But now, in our generation – in the past few years – a new resistance, in the form of several new practices of tyranny, has been making such headway that the fundamentals of 1776 are being struck down abroad and definitely they are threatened here.’’ At Independence Hall in 1962, John F. Kennedy spoke of the Declaration of Independence unleashing “not merely a revolution against the British, but a revolution in human affairs.” Calling it “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech depicted the Declaration of 1776 as “a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Speaking on July 4, 1986, Ronald Reagan said of those who signed the Declaration of Independence, “Their courage created a nation built on a universal claim to human dignity, on the proposition that every man, woman, and child had a right to a future of freedom.’’ To these leaders and those inspired by them, 1776 mattered. For American independence in all its forms, it still does.