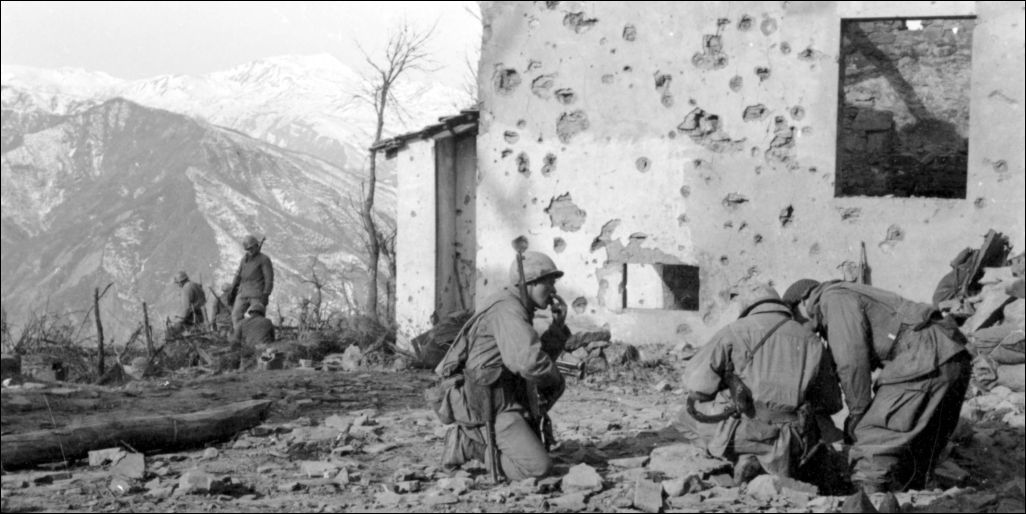

Allied soldiers struggled for months to clear veteran German troops dug into the mountains of northern Italy in late 1944 and early 1945.

-

Summer 2022

Volume67Issue3

Editor’s Note: The late Sen. Robert Dole and nearly one million other Allied soldiers continued to fight Nazi Germany in northern Italy after D-Day in 1944, when the world’s attention turned to France. A team from American Heritage recently traveled to Italy to find the spot where Dole was so badly wounded, and to learn more about this dramatic but often-neglected phase of World War II. We thank Gabriele Ronchetti, author of several books on the Italian campaign, and the other historians of the Gothic Line Association for their help in the research for this article.

Churchill called Italy the “soft underbelly” of Europe. It turned out to be anything but that as the Allies faced some of World War II’s most costly battles, from the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943 to Salerno, Anzio, Monte Cassino, and many other bloody encounters.

“In the year before D-Day, the Italian campaign was the single most important front in the war,” historian Gabrielle Ronchetti recalled. “The Allied plan was to use Italy as a bridge into Nazi Germany, to strike at the heart of the Third Reich. Little by little, over many months, the Allies fought their way up the peninsula, liberating Rome on June 5, 1944.”

Then, one day after Rome was taken, the world’s attention turned away from Italy as the Allies landed at Normandy to open up a second front in Europe. Seven American divisions were transferred out of Italy to help in France. But the Allies would continue to heroically struggle on the Italian peninsula, with little notice from the press and public.

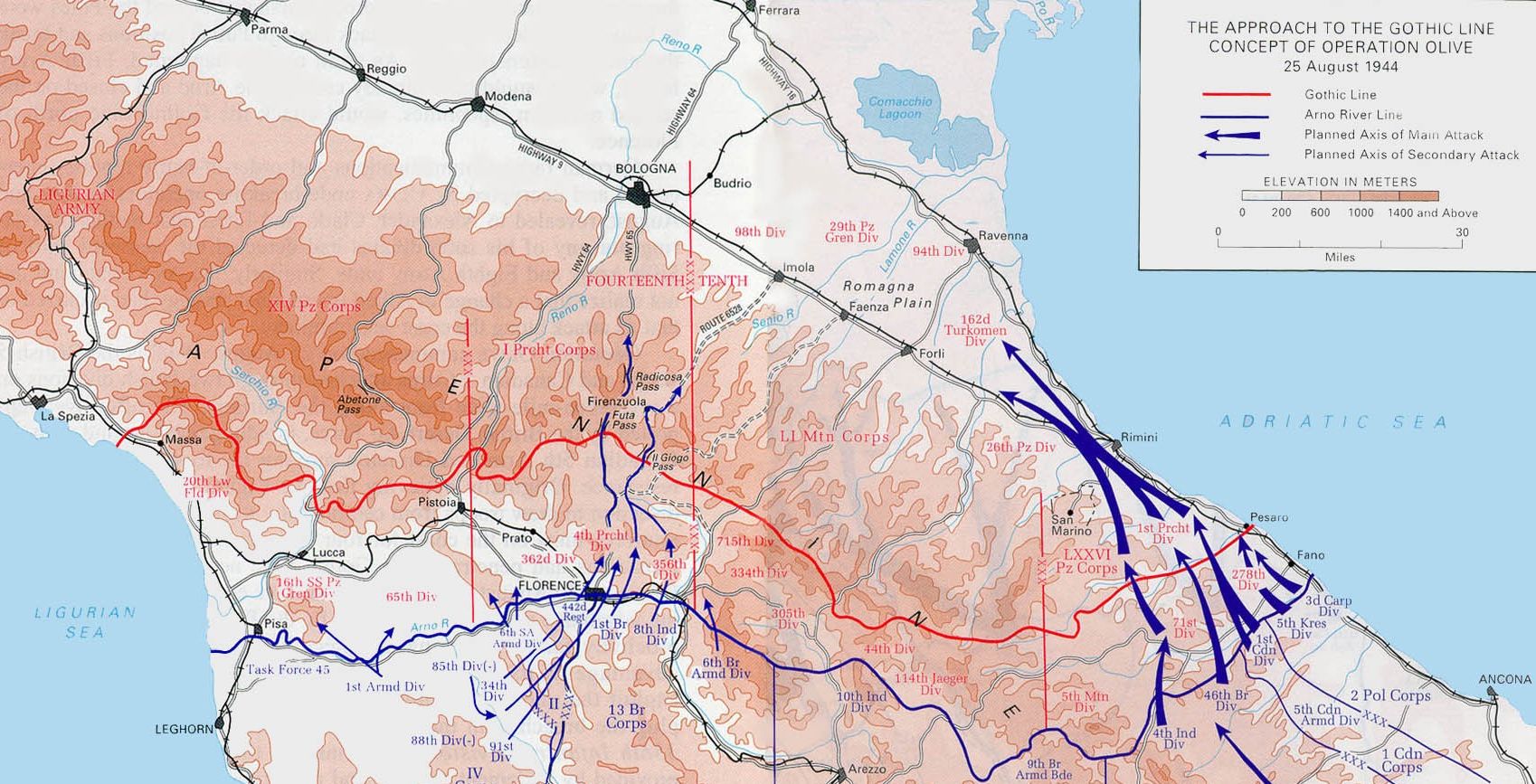

As the Germans retreated northward in late 1944, Hitler ordered them to fortify and hold what was known as the Gothic Line – two hundred miles of fortifications dug into the mountains from Pisa on the west coast to Rimini on the east. The Allies would face more than 2,000 bunkers, artillery, and machine-gun nests. These strongholds overlooked and blocked crucial roads that ran from Florence and Pistoia through the mountains to Bologna and the fertile Po Valley beyond.

The German commander was Albert Kesselring, one of the most decorated Nazi generals, who had led the operations in North Africa and was later convicted of war crimes, including the massacre of 335 Italian civilians in the Ardeatine caves outside of Rome.

“For the next three hundred days, the Germans held on tenaciously, knowing that, if they lost this ground, the Allies would pour through the Po Valley and make for the suddenly vulnerable southern borders of the Reich, and from there, on to total victory,” observed Bob Dole in his memoir, A Soldier’s Story.

The opposing armies fought on a massive scale. The Allies had 21 divisions, including six armored and 2,900 aircraft, for a total of almost a million men. The Germans had the remnants of 23 divisions, for a total of about 430,000, but no aircraft. The struggle would keep the Nazis tied down and unable to shift to the north to defend against the advance across France.

In the fall of 1944, Gen. Lucien Truscott, commander of the Fifth Army, assigned the center of the offensive against the Germans – the effort in the highest elevations – to the 10th Mountain Division, elite American troops specially trained in mountain-climbing, skiing, and survival in cold weather.

Five years earlier, the president of the National Ski Patrol had written a letter to Franklin Roosevelt proposing that the Army train special units for fighting in mountain terrain, citing the effectiveness of ski troops in Finland’s heroic defense against the Soviets earlier that year. “In this country, there are 2,000,000 skiers, equipped, intelligent, and able,” wrote Charles Minot Dole (no relation to Robert). “I contend that it is more reasonable to make soldiers out of skiers than skiers out of soldiers.”

Gen. George Marshall knew that the Germans had three divisions trained for mountain warfare, and that the Italians had just lost thousands of poorly trained men in the mountains during the Italo-Greek War. Marshall agreed with Dole’s idea and gave the go-ahead.

So, the Army had formed the 10th Mountain Division and recruited experienced skiers and university athletes. In addition to normal infantry instruction, these men underwent rigorous training in rock-climbing and mountain survival at Camp Hale, Colorado, at an elevation of 9,200 feet.

“The untrained mountain soldier has two foes – the enemy and the mountain,” noted an Army manual written for the division. “But he can make a friend and ally of the mountain by learning to know it. The mountain can give him cover and concealment, points of vantage and control, and even, at times, food, water, and shelter.”

Late in 1944, the 10th Mountain Division left for Italy packed into severely overcrowded troop transports – about 14,000 men in three regiments with additional units of artillery, medics, ambulance drivers, and other support. Arriving in Naples, the Americans were shocked by the sight of ships sunk in the harbor and so many buildings bombed to rubble.

The 10th Mountain was assigned to the Fifth Army, commanded by Gen. Lucien Truscott. They were ordered to move north to Florence and Pistoia, and then to dislodge the Germans from their strongholds that looked down on and blocked crucial roads that ran through the mountains to Bologna and the Po Valley beyond. At the same time, the British 8th Army would attack along the Adriatic coast in the eastern plains.

Gen. Truscott gave the 10th Mountain the daunting task of capturing 3,800-foot Mount Belvedere and the surrounding peaks in the center of the Apennine mountains on the border between Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna. These peaks were more than double the height of Monte Cassino that, months before, had been so costly to the Allies to capture. The mountains around Belvedere were covered with enemy bunkers and artillery manned by veteran German troops.

“Do you think you can do it?” Truscott asked the 10th Mountain’s commander, Gen. George Price Hays, a tough veteran of World War I and a Medal of Honor recipient. His men would need to carry 60- and 80-pound packs up steep mountains in the middle of winter in the face of an aggressive defensive.

“I don’t think I will have any division left,” Hayes answered soberly.

By early January, the first units had made their way north by train and foot to the mountains north of Lucca and Florence.

They hiked past burned farms, bombed churches, and villages of mostly rubble. Germans had placed mines and booby traps everywhere, and the Americans were in frequent firefights with enemy patrols.

“War spares nothing,” Sgt. Denis Nunan wrote home. “The isolated hamlets, with walls of stone feet thick, make fortresses for the enemy to gather strength within and strike out to kill.”

At the higher altitudes, there was four to five feet of snow. The men were issued four blanket each because the Army trucks didn't have chains yet and couldn't get sleeping bags and other supplies to their positions.

American patrols snuck up Riva Ridge, a series of peaks alongside Mount Belvedere, and came back with dismaying news. German defenses covered a half dozen mountaintops from 3,175 to 6,000 in height. Lt. Col. Henry Hampton wrote that he "felt like he was in the bottom of a bowl with the enemy sitting on two-thirds of the rim looking down upon you. There was about as much concealment as a goldfish would have in a bowl."

Advance parties under sniper fire searched for trails up the slopes. The routes were too rugged for jeeps or even mules, with grades of thirty and forty degrees, and some cliffs were so steep, they would need to be scaled with ropes. More advance teams drove pitons into rock to anchor the climbing lines, having wrapped their hammers with cloth to muffle the sound.

The day before the assault, Gen. Hayes addressed a large group of soldiers. The wiry general reminded some of his men of an old cowhand with a tanned and wrinkled face. He told them to keep pushing forward during the attack. “Never stop. Always forward,” urged Hayes. “If your buddy is wounded, don’t stop to help him. Continue to move forward. Don’t get pinned down. You must get into the enemy’s position as quickly as possible. You must move fast.”

Hayes did not say that headquarters had estimated his men would suffer a 90% casualty rate. At least the Americans had one advantage – some of the Germans had grown overconfident in their well-supplied and sheltered positions dug into high ground with panoramic vistas of the valleys below. They would not be expecting an attack up the sheer face of cliffs. But they would wake up soon enough.

The assault on Riva Ridge began in the evening of February 18, 1945. All through the night, soldiers struggled up steep paths in the darkness carrying heavy loads of equipment and ammunition. Some of the men ascended on ropes with heavy packs and machine guns on their backs.

Worried they would be heard by the Germans, the men hiked and pulled themselves up the ropes in silence. No one knew what to expect at the summit.

“Normally, we have just one medic with us. And this time, we’ve got about five or six medics,” veteran David Rankine later recalled. “I thought, ‘They’re expecting a lot of us to get wounded and killed.’”

Luckily, early the next morning, the defenders were largely taken by surprise. Gen. Hays later recalled that “the Germans were back in dugouts sleeping and our troops took the guns over, turned them around, and went down and threw hand grenades in their sleeping quarters, and that’s the way they woke up. The Germans were awfully surprised at the American soldiers ascending from a side that had been declared ‘unclimbable.’”

But, over the next several days, German counterattacks on the ridge lines cost 17 American lives, with 51 wounded and 3 missing. “On several instances, the Red Cross flag was used by the Krauts in an attempt to get into our positions, but this met with failure,” Lt. Col. Hamilton wrote in his report.

Special porter platoons carried ammo and supplies up the mountain, and Italian-speaking Americans supervised the work of local porters packing tons of equipment up the ridge with small local mules.

“By February 21, ten and 3/4 tons of ammunition alone had been packed on to the ridge, and there was never a shortage of ammo, rations, or water,” wrote Hamilton. “The men worked themselves to a point of exhaustion, some making three trips in a 24-hour period.”

Engineers set up an ingenious cable tramway to evacuate the wounded down the mountain and bring supplies up, the first time such a system was used in the war. The time required to get wounded men down the slopes was cut from 6-12 hours to four and sometimes just two hours. The lives of many wounded were saved.

Just one day after Riva Ridge was taken, six other battalions of the 10th Mountain began their assault on nearby Mount Belvedere. Over 13,000 men fought their way up the 3,800 foot mountain as they faced brutal machine gun and mortar fire.

By February 25, the Americans finally took control of the Mount Belvedere ridgeline. In the brutal fights for that mountain and Riva Ridge alone, nearly a thousand men would be killed or wounded in just the 10th Mountain Division.

After sustaining the terrible losses on Mount Belvedere, the men of the 10th Mountain worked their way north another 20 kilometers to Montese and Castel D’Aiano.

Newly-minted second lieutenant Bob Dole was assigned to the 10th Mountain in late February because so many of its young officers had been killed. Dole wrote in his memoirs that he thought it was “mighty odd” that “a kid from Kansas who had seen a mountain up close only once in his life would be assigned to lead a platoon of mountain troops.”

“We Kansans don’t ski much,” he continued. But “the army didn’t ask my opinion.” He didn’t mention that, at the University of Kansas, he had played on three varsity teams and later won track and field events in the Army.

The men in Company I of the 86th Regiment weren’t so sure about young Dole, however, especially Frank Carafa, the sergeant who had temporarily taken command of Company I after the previous lieutenant was killed.

“The very first day they brought him up to the lines and told me that he was taking over my platoon, I didn’t like him,” recalled Carafa about Dole. “I really had no reason, except that I was jealous because I was acting as platoon leader for the past fourteen, sixteen months and we were getting along very well. I was concerned about my men, their safety, and what not. And I didn’t know anything about him. I just heard that he was a new lieutenant, and that scared me.”

“Ninety-day wonders” like Dole were civilians trained to become junior officers in a relatively short time – unlike Sgt. Carafa, who had served for years in the army. “Half the lieutenants had been killed during the hellacious attack on Mount Belvedere,” recalled Dole. “No wonder the forty or so men of the 2nd Platoon didn’t go out of their way to get to know me when I arrived. They figured I wouldn’t be around long.”

“I had heard the stories of how the German snipers particularly went after the guys with stripes on the backs of their helmets and the soldiers with the binoculars and map cases,” Dole wrote later, “knowing that, if they could pick off the officers and the radio men, they would disrupt the chain of command. Our guys understood that.”

Sgt. Carafa admitted later that, after he spent time with Dole, “I did change my mind real fast.” But even so, he wouldn’t know his new lieutenant’s actual name until many years later. He thought it was “Doyle.”

After the new lieutenant’s 85th Regiment reached Castel D’Aiano in March, they rested and waited to continue the fight. “As the days passed by, we were more or less taking it easy,” recalled Sgt. Carafa. “He (Dole) fitted in with the fellas; he had his lunch and his breakfast and his dinner with us laying on the floor, on the ground, or sitting on a log or something like that. And we would joke around and everything else. He was just one of the guys. The men took to like him.”

Dole led his men on night patrols to watch for enemy incursions and to capture Germans for interrogation. On the night of March 18, he was badly wounded when a tossed grenade hit a tree, bounced back, and exploded nearby. “I saw a blast and felt a searing - hot pain in my leg, ripping my flesh open,” Dole recalled. “It was just a surface wound from the grenade fragments, but it hurt like crazy.”

The medics patched him up and he and his men pushed on in the darkness on the patrol, but to no avail that night.

In early April, the 85th and two other regiments were ordered to move out and attack the German fortifications, focusing on the 3,000-foot Monte della Spe, which they captured, despite heavy incoming mortar and artillery rounds. As they dug in, the Americans could see formidable German fortifications on flat-topped Hill 913 across the small Ombrina Valley. The Germans continued a bombardment 24 hours a day that kept the Americans in their foxholes, with their heads down.

On the morning of April 14, the men in Dole’s “I” Company were hopeful as a heavy fog finally lifted and allowed American bombers flying from Tuscany to blast the fortifications on Hill 913. “For the next forty minutes, wave after wave of bombers dropped their devastating loads on the German bunkers,” Dole recalled. Waves of Allied artillery fire battered the hill, and more bombers dropped napalm and turned the hill into “hell on earth.”

Veterans of the 10th Mountain later told historian Gabriele Ronchetti that, after what they had seen during the bombardment, they didn’t think there was even a single German up there anymore.

“The bombing is remembered as one of the biggest in the whole Mediterranean theater,” says Ronchetti. “But it didn’t have the effect it was supposed to. The Germans were still there.”

Ronchetti walked with visiting journalists over the battlefield that once was a treeless landscape of dusty, gray-brown soil and rocky hedgerows. It’s now lush, green farmlands and forests, but many of the surrounding hills still contain trenches, rocky pits for snipers and artillery, and log-covered dugouts where soldiers once slept or gathered for meals or medical attention.

Eventually, Gen. Hayes ordered the 85th to take Hill 913 – move down the slope, cross the ravine, and then head up a thousand feet of steep, open fields divided by hedgerows. The top of Hill 913 was 150 meters above the base of the ravine. Meanwhile, two other regiments in the division, the 86th and 87th, were sent against the nearby hills of Torre Lussi and Roffeno.

“About the time the platoon in front of us got over a stone wall, and forty feet or so into the clearing, someone stepped on a land mine, and someone else hit another,” Dole recalled. Then the Germans opened fire; the massive bombings clearly hadn’t destroyed the defenses. “They started pouring artillery, machine gun, and mortar rounds into the clearing in front of us, mowing down dozens of American soldiers, shredding others, pulverizing still more.”

Dole and his men heard machine-gun fire coming from a farmhouse on the hill above. Twenty-five or thirty men were already down. The company commander ordered Dole’s platoon to move to the left to flank and take out the farmhouse, with Sgt. Carafa taking the lead. But Dole, knowing it was a highly risky operation, elected to take point himself.

“Raw anger surged through me as I saw so many of our guys falling,” Dole recalled. “I took part of a squad from the platoon with me toward the left, while Carafa rounded up the rest of the guys and got them in position, ready to fire at the farmhouse straight on, as we attempted to come in from the side.”

“I felt a sting, as something hot, something terribly powerful crashed into my upper back behind my right shoulder,” Dole later recalled. “I’d often been hit in the back by a hard-charging linebacker when I’d caught a football in high school or college. Occasionally, I’d been thrown to the ground and stomped on by a couple of college linemen after making a catch. But nothing in my life ever hurt like the shock that seared through my shoulder just then. My body responded before my brain had time to process what was happening. As the mortar round, exploding shell, or machine gun blast — whatever it was, I’ll never know — ripped into my body, I recoiled, lifted off the ground a bit, twisted in the air, and fell face-down in the dirt.”

“For a long moment, I didn’t know if I was dead or alive,” Dole recalled. “I sensed the dirt in my mouth more than I tasted it. I wanted to get up, to lift my face off the ground, to spit the dirt and blood out of my mouth, but I couldn’t move. I lay face down in the dirt, unable to feel my arms. Then the horror hit me — I can’t feel anything below my neck!”

“My men started calling me, ‘Hey Sarge. The Lieutenant’s been hit. He’s calling you,’” Carafa recalled in an interview. “So, I crawled down close to the opening of the ravine and I looked up in the ravine and I could see the whole squad of men laying down. I could see the lieutenant moving. I saw one other man move, and I just didn’t know what to do. There was one man about ten yards away from me. He started moaning and he moved. Seeing him, I don’t know, something came over me and I started crawling out to see if I could help him. When I got to him, I started dragging him back.”

“Guys were being blown up and wounded,” Carafa recalled. “I don’t know what happened to me. It was like God was on my shoulder.”

The sergeant then came to two of his men who were dead. He crawled to the next man who was wounded and pulled him back.

“Not knowing what the hell I was doing, I just turned around and started crawling out there again,” Carafa said. “I could hear the bullets going over my head. I kept crawling. Two more were dead.

“I finally reached the lieutenant," continued Karafa. "His arm was outstretched and I grabbed his arm and I yanked him. He gave a holler and passed out. I couldn’t even budge him. I was 5’5”, 145 pounds. He was a six-footer and close to 200. I just kept praying to God to help me. I finally got some strength and I started dragging him. And I dragged him a little ways, and I couldn’t drag him any more and I started to roll him down the incline, which is much easier. I finally got him back and he was all shot up. His whole right side, from his shoulder down to his waist.”

“When Sergeant Carafa attempted to yank me by my arm, it felt as though what remained of my arm was going to come off in his grip,” Dole recalled. “I conked out after that, although I was later vaguely aware of being rolled over and over again, my head and face bouncing off the rocky terrain like a softball hitting the pavement.”

Dole was paralyzed from the neck down, and his injuries were so bad, the medics gave him the largest dose of morphine they dared and wrote an “M” for morphine on his forehead in his own blood so that no one else would give him a second dose, which might have been fatal.

Sgt. Carafa and the regiment had been ordered to leave the dead and wounded for the medics and continue the attack, so they pressed on up Hill 913.

“Dislodging the Germans from the high ground came at a horrendous price," wrote Dole later. "The Americans suffered more than 460 casualties on April 14, with 98 men dead following the day-long assault on Hill 913.”

After recovering from an infection that nearly killed him, Dole would spend two years in hospitals recovering from the terrible wounds that left him with limited mobility in his right arm and numbness in his left arm.

In 1947, Dole was medically discharged from the Army as a captain. He would receive two Purple Hearts for his injuries and the Bronze Star with "V" for valor for his attempt to assist a downed radioman. He minimized the effect in public by keeping a pen in his right hand, and learned to write with his left hand.