Enormous crowds greeted the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolution, during his visit to all 24 states nearly 40 years after the war ended.

-

Summer 2024

Volume69Issue3

Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Reese is the author of the recently published book, Marquis de Lafayette Returns: A Tour of America's National Capital Region. She also serves as chair of The American Friends of Lafayette Bicentennial Committee for Washington, D.C. and is pursuing a graduate degree in history at Gettysburg College.

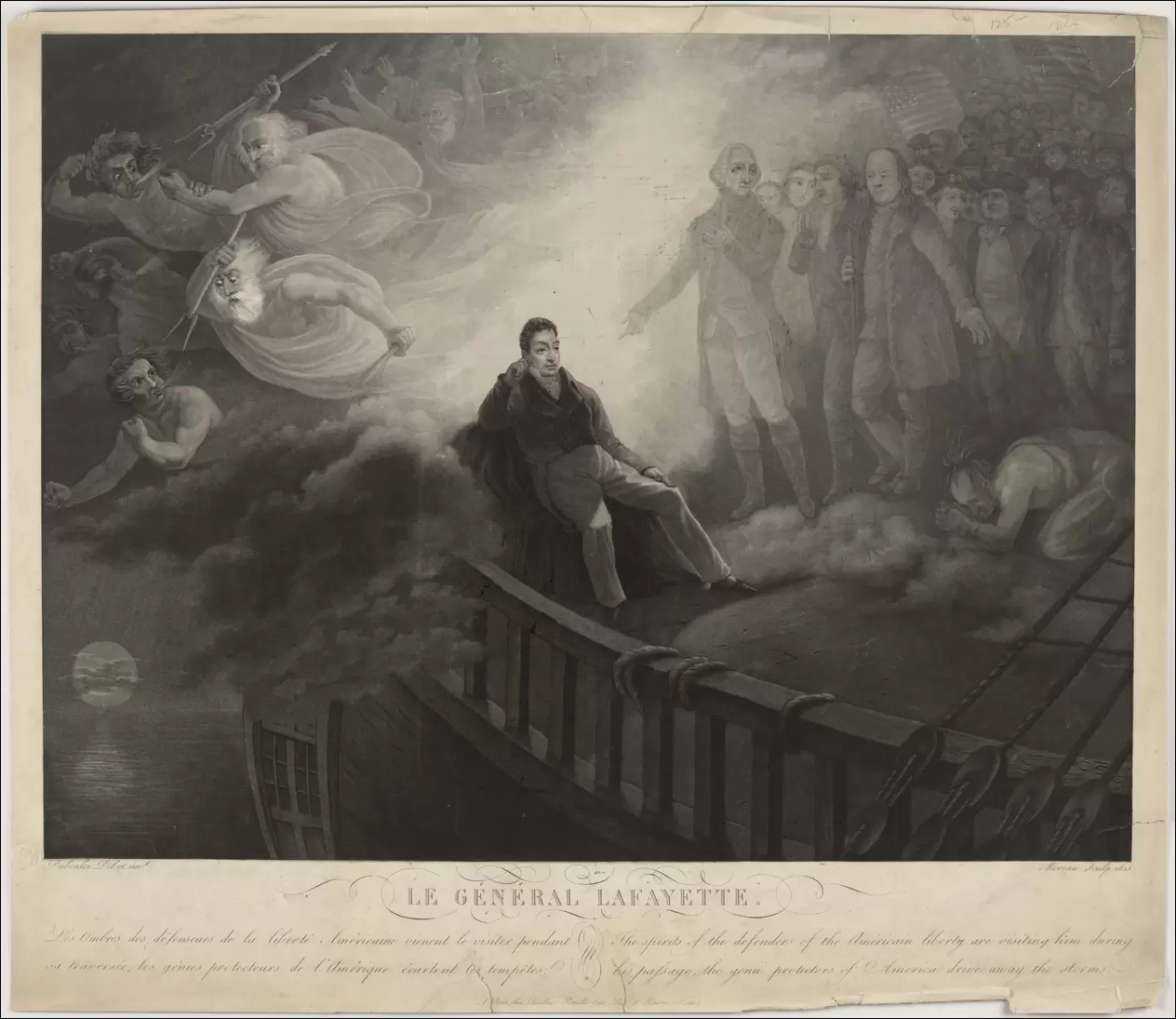

When the Marquis de Lafayette sailed into New York Harbor in August 1824, the entire city came out to greet him. Tens of thousands of spectators crowded the shoreline at Castle Clinton, the southernmost point of the island of Manhattan, to watch him set foot on American soil for the first time in 40 years.

As the 66-year-old hero of the American Revolution descended from the ship that had carried him back across the waves to the shores of the nation he had selflessly served as a young man, a roar crescendoed from his admirers. For the next 13 months, Lafayette would travel to each state in America, welcomed by cheering crowds everywhere.

The year 1824 found the United States on the cusp of a monumental celebration; the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence was on the horizon, and Americans were buzzing with patriotic excitement. Only ten years earlier, America had been at war with Great Britain again; the presidential mansion (renamed the White House after its restoration) the Capitol, the Navy Yard, and other federal buildings were burned by the invaders. And Lafayette had experienced his own struggles after the Americans achieved independence, surviving the turbulent years of the French Revolution in solitary confinement and then in exile in Olmutz, in what is now the Czech Republic.

After touring the northeastern states, the marquis arrived in Washington, D.C. on October 12, 1824. A far cry from the sprawl of elegant marble Romanesque buildings of today, the city was largely confined to the area later known as Capitol Hill. The carriage route from Baltimore to the capital featured unpaved roads, sparse lodging, and farmland.

Lafayette’s valet, Auguste Levasseur, wrote in his journal that he was less than impressed with their entrance into Washington: “Drawn on a gigantic scale, the plan of Washington cannot be filled out for a century. Only the space separating the Capitol Building from the President’s House is inhabited, and this space has already formed a medium-sized town.”

The parade into the District of Columbia was a military procession fit for a president, stretching from the city limits bordering Prince George’s County, Maryland all the way to the Capitol. Over 1200 volunteer troops from Washington, Alexandria, and Georgetown helped to escort Lafayette toward Capitol Hill, with spectators’ cheers mingling with the sounds of artillery fire to mark the occasion.

The sheer volume of people and the planning for such an event had “never been equaled here on any former occasion,” wrote a reporter for the Washington Gazette.

One wonders what Lafayette thought as the residents of the capital city, named in honor of his beloved friend and virtual surrogate father, came out to greet him. The mere existence of the city represented the ideals of the Revolution come to fruition: a city where those elected by the people come to serve. His arrival was welcomed with pageantry; a massive archway was arranged at the east entrance of the Capitol grounds and decorated with evergreen branches. A live eagle perched on top of it.

As he ascended the steps of the newly completed Capitol building, men and women crowded into every inch of the building, hoping to catch a glimpse of him. Contemporary images of Lafayette’s visits often capture the kinetic energy generated by his presence, with spectators rushing to greet him amid cannon fire, and windows crowded with onlookers.

This scene would be replayed nearly every day of the grand tour. Each city and town that Lafayette passed through, large and small, would replicate this pageantry of appreciation. This was one of America’s first documented cases of tourism on such a massive scale; people had traveled from afar to participate. In smaller cities, the number of people who came to greet Lafayette frequently outnumbered the recorded populations of the time. When Lafayette spent the winter of 1824-1825 in Washington D.C., temporary lodging in boarding houses and taverns was filled to capacity.

The New York Mirror and Ladies Literary Gazette summarized this frenzy in August 1824: “Gentlemen are ready to throw by their business to shake him by the hand, and ladies forget their lovers to dream of him. If a man asks 'Have you seen him?,' you know who he means.”

The energy around "the Nation’s Guest" brought Americans together in a way that was unprecedented. The fact that he was nearly universally beloved may have been due in part to the fact the French Revolution kept him in Europe. Shortly after Lafayette’s release from his five-year imprisonment, America entered the Quasi-War with Lafayette’s home country in 1798, which mainly involved naval clashes along the east coast and in the Caribbean as a result of French privateers having seized American ships.

Little blood was shed in this two-year conflict, but relations between the two powers were strained for some time. Lafayette had written to friends in America about the possibility of seeking asylum here. His pleas fell upon sympathetic, but unhelpful, ears.

Though he had a good personal connection with the marquis, Alexander Hamilton wrote to Lafayette on April 28, 1798: “I have never been able to believe that France can make a republic, and I have believed that the attempt while (the chaos in France) continues can only produce misfortunes. Among the events of (the French) revolution, I regret extremely the misunderstanding which has taken place between your country and ours, and which seems to threaten an open rupture.”

Despite his harsh words, he closed his letter with a sentiment that would define Lafayette’s legacy for decades to come - “The only thing in which our parties agree is to love you.”

Hamilton was correct, though perhaps unintentionally. Early American politics were bitterly divided by the antagonisms between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. By remaining outside the fray, Lafayette never had to choose a side.

His popularity and neutrality would take center stage during the tumultuous presidential election of 1824, which overlapped with the National Tour. With Americans torn between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, tensions in Washington especially were at an all-time high. The election was the first in which neither of the top candidates had served in the Revolution or had a hand in the country’s founding documents. Without the rose-colored memories of the founders to guide voters, the nation was at a crossroads. What was the path for the future of the presidency? Was it reserved only for those connected to the family names of the glorious fight against the British, or would America be a country in which the common man could be elected to the highest office?

Lafayette’s mere presence during this time was a stern reminder that embers of the Revolution were dying, out and it was the responsibility of the next generation of Americans to carry the torch into a new era. Though he did not personally sway politics by publicly endorsing a candidate, politicians and citizens alike were often on their best behavior in his presence. Elected officials, who just the day before were engaged in screaming matches or fisticuffs with each other, were sitting side by side at Lafayette’s table raising a toast to him and the prosperity of America. Partisan newspapers published scathing attacks against their opponents alongside glowing accounts of Lafayette’s visit.

Because neither John Quincy Adams nor Andrew Jackson had won a majority in the Electoral College, the House of Representatives decided in Adams' favor. Lafayette was in the House chamber when Adams was declared the sixth president of the United States.

While the American Revolution is typically seen as the birth of a new age, Lafayette returned to America when most of the heroes of the war were either dead or very old. Americans born in the decades after the war’s end were dependent on the oral history of older relatives to understand the nation's sacrifices during the eight-year war that left at least 25,000 Americans dead.

Lafayette’s long visit was a dramatic reminder of what the Revolution was and what it meant to Americans as the memory of the war was starting to fade.

The effects of this lasted long after he returned to France in September 1825. In the wake of his visit, Americans continued to honor him. Hundreds of cities, streets, institutions, and public spaces were named after him. Many parents, perhaps hoping that a namesake would invoke the Revolutionary spirit, named their sons Fayette. For some of the cities that the marquis visited, the attention he paid to them remains one of the highlights of their histories to this day.

Despite this, Lafayette is something of a quiet presence in the American memory. His visage is not on any currency; no marble obelisk honors him, but he is still very much part of America. On December 10, 1824, he became the first foreign dignitary to address Congress. This recognition marked the national importance of his visit and highlighted his service during the Revolution. Congress awarded him a repayment of his expenses during the war. To this day, Lafayette is the only private non-citizen to have addressed the chamber.

Before he died in 1834, his final wish was to be buried alongside his wife in Picpus Cemetery in Paris, under soil that was collected from Bunker Hill. Upon hearing the news of his death, America mourned. President Andrew Jackson ordered the same funeral honors and mourning that had been observed for George Washington. Flags were flown at half-mast, members of Congress wore mourning bands, and the chambers of Congress were decorated in black bunting.

For all the mutual love between Lafayette and America that the tour embodied, it would take some time before the federal government formally honored him with citizenship. While Maryland and Virginia had awarded him honorary citizenship prior to the ratification of the Constitution, Congress did not do so until 2002. When the joint resolution was signed by President George W. Bush in August of that year, Lafayette posthumously became only the sixth person to receive that honor.

In 1824, Americans celebrated Lafayette as one of their own, politics aside. He was simply the representation of liberty, of freedom and justice for all, ideals that are bipartisan at their very core. He left behind an important legacy in America. In the midst of political strife, he brought unity. His presence was a physical reminder of the burning embers of the Revolution: friendship, bravery, and patriotism. His departure marked a moment of finality; the Founders were gone and America was left to chart its own course, which is perhaps the greatest experiment of all.

The bicentennial of Lafayette’s National Tour will kick off in mid-August 2024 in New York City. The American Friends of Lafayette, a non-political historical and patriotic society dedicated to the memory of Major General Gilbert Motier, Marquis de Lafayette and to the study of his life and times in America and France, will follow the route of Lafayette’s journey. Traveling across 24 states over 13 months, it will give the nation the opportunity to celebrate Lafayette once again on a grand scale. To learn more about the bicentennial or to get involved, please visit: lafayette200.org.