Though it was one of his most controversial actions as president, Richard Nixon's covert bombing of Cambodia was excluded from his impeachment articles, helping to shape how the Vietnam War has been remembered ever since.

-

Summer 2024

Volume69Issue3

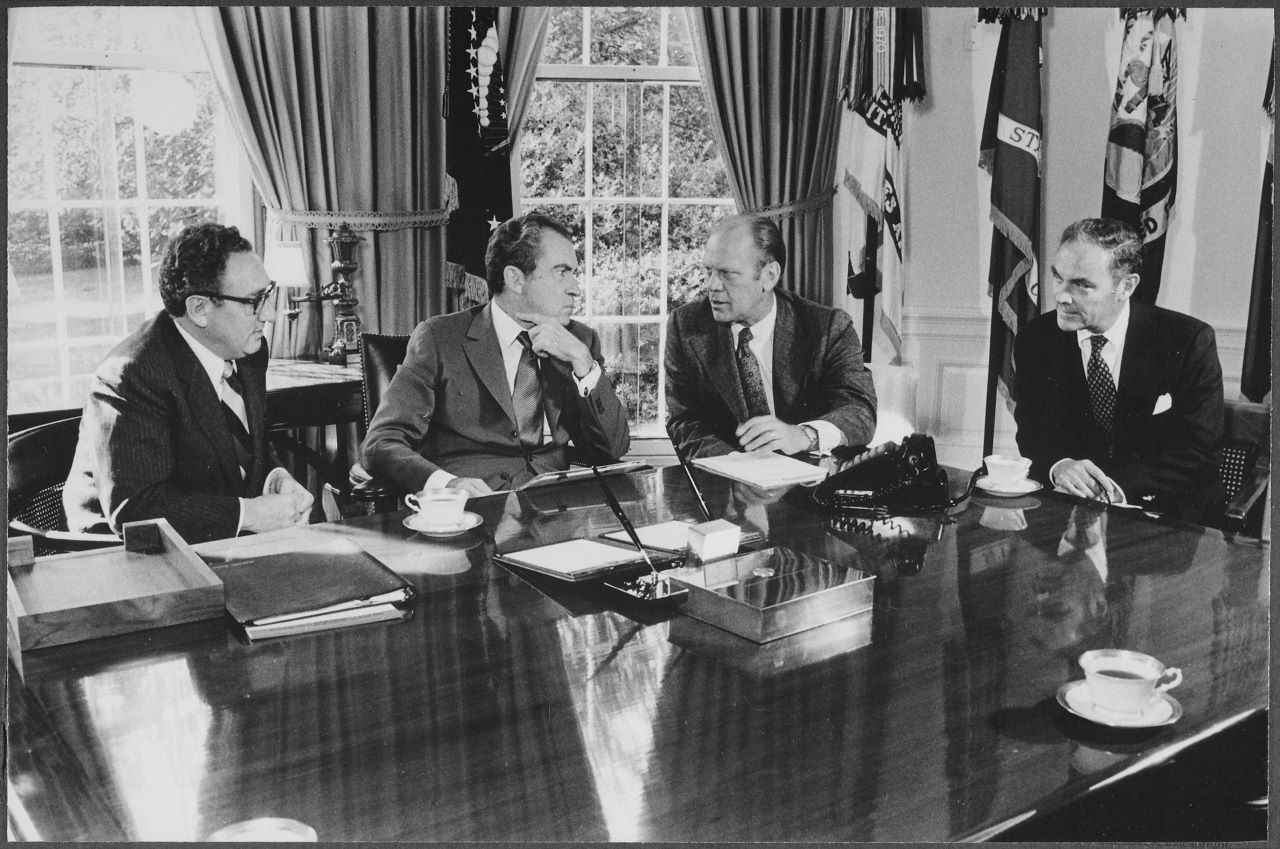

Editor's Note: The following was adapted from Carolyn Woods Eisenberg’s recent book, Fire and Rain: Nixon, Kissinger, and the Wars in Southeast Asia.

It was viewed as an awesome responsibility. For members of the House Judiciary Committee, whatever they had said about Richard Nixon in the past, whether in anger or admiration, the decision to approve articles of impeachment weighed heavily. If approved, it would go to the full House of Representatives for a vote; and if the vote was in favor of impeachment, then the Senate would decide whether the president was guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

While theirs was only the first step in the process, members of the committee had strong reasons to believe that what they collectively decided could determine the fate of the president of the United States. More than a century had passed since the last time Congress had entertained such a possibility. And it was no small thing to unseat a president—especially Richard Nixon, who, in his re-election effort, had carried every state in the union but one.

From May 9 through July 30, 1974, the Committee (consisting of 36 men and two women) pored over books of documents, questioned witnesses, weighed the arguments of counsel, and debated with one another. Its chairman, Democrat Peter Rodino, wanted to focus on the first three articles of impeachment. Seeking to minimize party divisions, he believed that those three were the most likely to find some measure of bipartisan support. Each of those pertained to domestic crimes linked in some fashion to the Watergate break-in and subsequent investigations.

Since June of 1972, when seven men were arrested for illegally entering the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate Hotel, there had been a steady drip and then a flood of revelations about the administration’s misuse of power. This break-in, which seemed inexplicable on the surface, had been executed by a “Plumbers” group connected to the White House and specifically to the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP). The Plumbers, it emerged, had been responsible for illegal eavesdropping, burglaries, intimidation, and “dirty tricks.”

Because the connection to the White House would be so damaging to Nixon if it came to light, there had been a wide-ranging cover-up designed to insulate him from the crime. During the 1972 election season, White House lawyer John Dean had successfully managed this task. However, since the inauguration, the official story had steadily unraveled, and by the spring, Dean himself had become a hostile witness. Over the following year, more details had emerged about the administration’s illegal efforts to suppress this and other scandals. By the time the House Judiciary Committee convened, key members of the president’s team were facing felony charges, among them former Chief of Staff H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, Assistant to the President John Ehrlichman, Special Counsel Chuck Colson, and former Attorney General John Mitchell.

Given the weight of evidence, it was no surprise that a majority of the committee voted in favor of the first three articles: Article I, which accused the president of personally acting to obstruct justice in the Watergate case; Article II, charging him with persistent misuse of his authority in upholding the country’s laws; and Article III, faulting him for defying subpoenas of his records and withholding other evidence pertinent to the impeachment process. With their passage, it became unlikely that Richard Nixon would finish out his term of office.

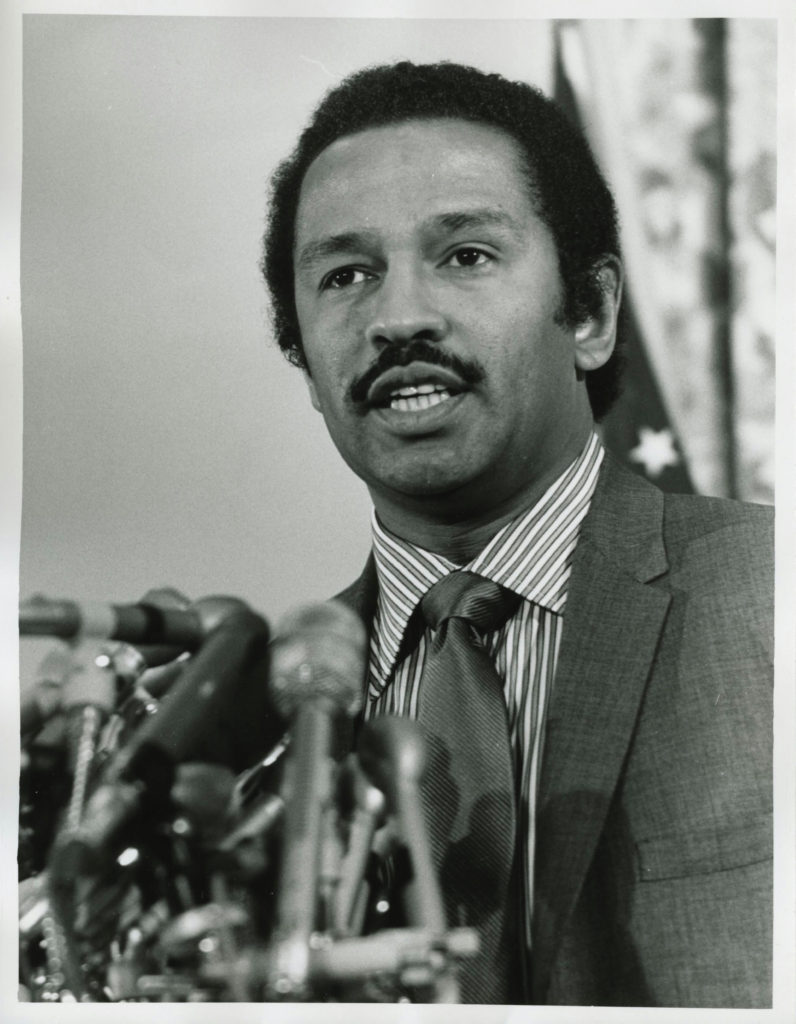

Cast into oblivion were two other articles of impeachment, which were rejected by a majority on the committee. One of these had relatively narrow significance—the accusation that the president had underpaid his federal income tax and accepted government financing of improvements to his homes. But Article IV had a much wider reach and sparked intense debate among committee members. Introduced by Representative John Conyers of Michigan, it charged the president with “the submission to the Congress of false and misleading statements concerning the existence, scope, and nature of American bombing operations in Cambodia in derogation of the power of the Congress to declare war, to make appropriations, and to raise and support armies.”

For some Americans, any reference to Cambodia could evoke deep emotions. The uproar surrounding the president’s decision to send troops in April 1970 had produced the largest antiwar protest of Nixon’s first term, culminating in an explosion of dissent and some violence on college campuses, most memorably the shooting and deaths of four students at Kent State University.

The American invasion of Cambodia, which had been publicly announced, was not the primary focus of the proposed article. Instead, it was the fourteen months of covert bombing of Cambodia that Nixon had ordered prior to the ground invasion. During this period, B-52 bombers had launched 3,695 attacks on that country, despite the president’s repeated insistence that the United States had never intervened there before the invasion.

The dishonesty of that claim had only garnered attention in July 1973, when retired Major Hal Knight testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that, in his capacity as supervisor of radar crews in South Vietnam, he had helped falsify the flight records of at least two dozen missions by disguising American air strikes in Cambodia as attacks inside South Vietnam. In an elaborate arrangement, the real coordinates for the planes were hand-delivered to Knight by a courier from General Creighton Abrams’ headquarters in Saigon, and then given to the pilots. Once the flights returned, there was a dual system of reporting in which fake information was entered into the Pentagon computers, while Knight would gather and burn the incriminating documents. To signify a successful mission, he would place a call and report to an anonymous official in Saigon: “The ball game is over.”

The Senate Armed Services Committee quickly learned that Knight’s experience was part of a larger pattern of falsifying records to hide the bombing of Cambodia from the American public and Congress. So far-reaching was the secrecy surrounding this undeclared war that even the civilian Secretary of the Air Force, Robert Seaman, was not informed.

Who had orchestrated the elaborate system of deception? In the aftermath of Knight’s testimony, many wished to know. However, one thing was clear: President Nixon had ordered both the bombing and its concealment. By so doing, he had effectively denied members of Congress the opportunity to debate or vote on whether to authorize this military action in an officially “neutral” country.

Unlike the other charges the Judiciary Committee had considered, the veracity of the Cambodia charge was not disputed. Whatever the motive, the Nixon administration had clearly deceived Congress, with the intent to sidestep its prerogative to declare war and appropriate funds for that purpose. John Conyers wanted the Judiciary Committee to reaffirm that legislative responsibility:

"Many people don’t know or have forgotten that the Congress constitutionally has that sole authority. And so, I would urge that we - in an attempt to reassert those powers which we consider vital and precious, if the constitutional form of government is to prevail and continue and improve - that we give the gravest consideration to this article."

He also contended that it was the desire to hide the bombing that had led to the “unparalleled” use of wiretaps and illegal surveillance of journalists and government officials.

The congressman was referring to events prompted by a May 1969 New York Times article in which Pentagon correspondent William Beecher reported that American B-52s had struck Vietcong and North Vietnamese supply dumps in Cambodia. This story had gone nowhere, but had nonetheless infuriated Nixon and Kissinger. So eager were they to identify those who had leaked the story to Beecher that, at their behest, the FBI had placed warrantless wiretaps on 13 government officials, several of whom were on Kissinger’s staff, and on four members of the press. In Conyers’ view, this was “the beginning of a policy of corruption” that had gone on for years.

While he had limited his proposed article of impeachment to the specific lies about Cambodia and the resulting wiretaps, the Congressman saw a direct link between the crimes of Watergate and the administration’s lawless conduct of the Vietnam War. Two years earlier, when the Nixon administration had resumed the bombing of North Vietnam and begun the mining of Haiphong harbor, Conyers and several colleagues had taken out a two-page ad in the New York Times arguing that these were impeachable offenses.

Partly for this reason, Chairman Rodino and some other Democrats on the Judiciary Committee were worried about Article IV. In their view, drawing too tight a connection between the process of impeachment and opposition to the Vietnam War would be needlessly divisive at a time when they were seeking consensus. Father Robert Drinan, the antiwar congressman from Massachusetts and a Jesuit priest, objected to this reasoning. He did not believe that “the process for picking articles of impeachment (should be influenced by) whether they will fly,” rather than by the gravity of the infraction. The Founding Fathers had recognized that “the ultimate tyranny was war carried on illegally by the executive without the knowledge or consent of Congress.”

Yet many on the committee did not agree. As Ohio’s Republican Congressman Delbert Latta stated, “this was a time of war,” when, inevitably, things happen “that you don’t put on the front page of every newspaper.” He felt that Nixon’s overriding concern had been to protect American troops and bring them home safely. To the extent that military action in Cambodia had contributed to that result, this was a reason for gratitude. Few of Latta’s Republican colleagues went that far, but several maintained that there was shared culpability for the constitutional violations that had been committed during the Vietnam War, and that it was unfair to single out President Nixon.

And it was not only Republicans who had objected to Conyers’ article. Representative Walter Flowers, a Democrat from Alabama, said that Nixon was getting “a bad rap” on this matter. “We might as well resurrect President Lyndon Johnson and impeach him posthumously for Vietnam and Laos.”

For John Conyers and his newly elected colleague, Elizabeth Holtzman (D-NY), getting Article IV on the agenda had been an uphill struggle. In allocating staff resources, the opportunity for debate, and access to prime-time television, the committee chair had sought to marginalize their concern. Up through the final day of the proceedings, Rodino had pressured the Detroit congressman to drop it. Yet Conyers stood by Article IV, maintaining, “This is not frivolous, Mr. Chairman.”

Even those who understood the seriousness of the issue raised in Article IV did not necessarily want to proceed with it. John Seiberling, who represented the Ohio district where Kent State is, acknowledged that “the issue is the falsification of information, the misleading of Congress, the failure to consult Congress on a matter as grave as an act of war.” In his view, four students had died because “the president of the United States again abused his power and again invaded Cambodia without consulting the Congress.” Such behavior was reprehensible and must not be tolerated in the future, yet Seiberling argued that “we should not use our impeachment power to impeach” Nixon for “acts of the sort which other presidents have taken with impunity . . . and for which the Congress bears a very deep measure of responsibility.”

Proposing to exonerate the president on the grounds that his predecessors had engaged in similar behavior and that past members of Congress had been indulgent was a curious line of argument. For those who supported Article IV, however, it seemed clear that it was more important to establish a precedent for punishing any violation of Congress’ constitutional right and responsibility to make decisions about going to war. Congressman Wayne Owens of Utah expressed his “hope that we will set down a standard for presidents and future wars, that something positive will come out of . . . the history of this sad war in Southeast Asia and the history of this sad proceeding,” In subsequent years, perhaps the American people, acting through their elected representatives, would openly decide questions of war and peace “just like the Constitution requires.”

Conyers, Holtzman, and several others on the Judiciary Committee considered that secretly bombing a neutral country 3,600 times and lying to Congress about it was so egregious that Article IV article should have been approved so that the entire body of the House could vote on it. Nonetheless, when the roll was called, every Republican voted against it, as did nine of their Democratic colleagues.

While members of the Judiciary Committee were casting their historic votes, the New York Times published a series of articles by Sydney Schanberg, who was reporting on the ground in Cambodia. Five years after Nixon had ordered the bombing of that country, and four and a half years after the overthrow of its head of state, Prince Sihanouk, Cambodia was ravaged by the civil war that had resulted from those events. Writing from the town of Oudong, Schanberg described the aftermath of a battle between the government and the brutal insurgents known as the Khmer Rouge: “Forests have been mowed down, schools, pagodas, mosques, and hospitals have been flattened.” The same was true of nearby towns such as Prek Kdam and Kompong Luong and the villages in between.

Many of the 20,000 residents of Oudang were captured by the rebels when they retreated into the jungle. The rest had escaped to the capital of Phnom Penh. Schanberg described the appalling conditions in this once-beautiful capital city. Thousands of homeless children roamed its streets, begging for food. Five years earlier, Phnom Penh had a population of 600,000, but the mass arrival of refugees had swelled that number to more than two million, vastly exceeding the capacity of the residents to absorb them: "Some have wood or plastic as lean-to covers to keep off the weather and some have straw mats to lie on. Others simply live in the open, sleeping in their dirty, tattered clothes on pieces of cardboard. Garbage is often piled nearby, and rats occasionally slither over sleepers."

Illness was naturally on the increase. In addition to dysentery and tuberculosis, refugees had a common vitamin deficiency called speuk, which caused a progressive loss of sensation in the feet and legs until a person could no longer walk.

With political events of great magnitude occurring in Washington, few people were focused on what was happening in Oudang, Pred Kdam, Kompong Luong, or even Phnom Penh. Ignoring the life-altering consequences of America’s war in Southeast Asia was not unusual for Americans. In voting down Article IV, the members of the Judiciary Committee effectively sanctioned that willful ignorance and denial, and ensured that President Nixon would not face responsibility for the tragic events his invasion had set in motion. All the articles of impeachment that would be brought before the House were connected to the domestic crimes brought to light by Watergate. This meant that constitutional issues of the gravest importance would be overlooked in any impeachment proceeding.

In June 1974, one of America’s foremost historians, Henry Steele Commager, had warned against obscuring the deeper constitutional issues that were raised by the administration’s misconduct. Nixon had already won a strategic victory, he wrote, “in the realm of public, and perhaps even of Congressional opinion,” by successfully “concentrating attention on Watergate and its associated chicaneries.” The minority on the Judiciary Committee who registered their dissent over the exclusion of Article IV expressed similar concerns: "By failing to recommend the impeachment of President Nixon for the deception of Congress and the American public involving an issue as grave as the systematic bombing of a neutral country, we implicitly accept the argument that any ends, even those that a president believes are legitimate, justify unconstitutional means."

After the fact, one could reasonably argue that the particulars of the impeachment articles made no practical difference—what mattered was that the Judiciary Committee had determined that Nixon was unfit for office, and this finding had caused him to resign even before the House of Representatives could begin its deliberations. Yet, by excluding foreign military activities from those articles, the committee framed how the events of that time have been remembered ever since. Although the illegal actions of Nixon’s domestic officials were exposed, the central role of National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger was effectively spared congressional scrutiny and critique.