A Chinatown cook's fight to re-enter the U.S. in 1895 went up to the Supreme Court, which upheld his claim to birthright citizenship and guaranteed it for all through the 14th Amendment.

-

Fall 2025

Volume70Issue4

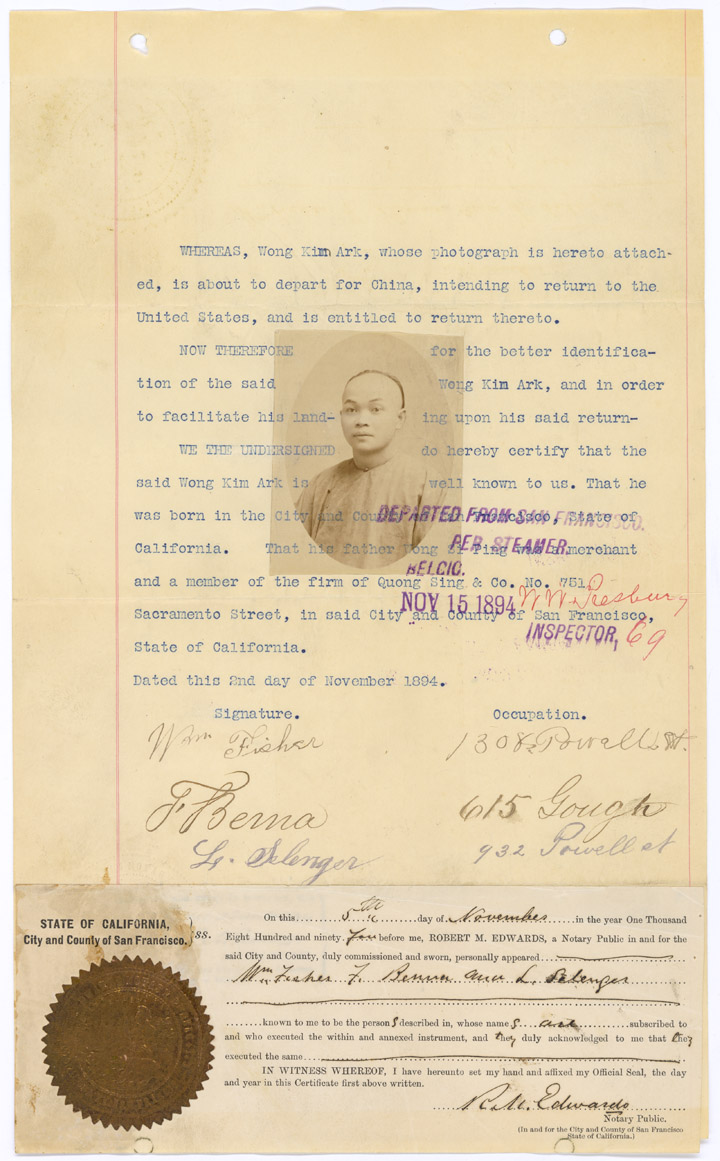

When Wong Kim Ark, a 21-year-old cook, left California in November 1894 to visit relatives in China, he planned to return to San Francisco, his birthplace and his home. He had made a similar trip to China in 1890, and the customs collector had allowed him to re-enter the United States without incident. Nonetheless, his current journey was not without risk. Anti-Chinese sentiment was strong, especially in California. Federal law barred Chinese laborers from entering the country, and customs officials had become increasingly vigilant in enforcing this exclusion. Only Chinese workers who were U.S. citizens could come ashore.

Even though his parents were non-citizen Chinese immigrants, Wong saw himself as an American citizen because he had been born here. To be safe, he obtained an affidavit, with his photo affixed, in which three Caucasian citizens swore that he had been born in San Francisco, and his own written statement, swearing that he had been born here and had been permitted to re-enter as a citizen in 1890.

In August 1895, Wong’s steamship, the S.S. Coptic, docked in San Francisco Bay. There was a new customs collector, stricter than his predecessor, and he refused to let Wong land. Wong wore a queue, dressed in traditional Chinese garb and was less than fluent in English. The customs collector, John H. Wise, saw a Chinese laborer illegally trying to enter the country, not a citizen returning home. He confined Wong on a ship in San Francisco Bay. Thus began the process that would propel the question of Wong’s citizenship to the nation’s highest court for a ground-breaking ruling that would make the young Chinese-American cook the focus of a battle that reverberates today, with the latest salvo being President Donald J. Trump’s attempt to severely limit citizenship for those, like Wong, born here of non-citizen parents.

In early America, it was assumed those born in this country were citizens. This principle, called birthright citizenship, had emigrated from England but had never been codified in the Constitution or federal statute.

The end of the Civil War thrust birthright citizenship to the forefront because the status of more than 4 million recently freed slaves was in limbo. While most of these ex-slaves had been born here, they were not citizens because the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision had barred African-Americans from citizenship.

In January 1866, Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois introduced legislation to legitimize the status of the former slaves and to codify birthright citizenship. Initially, the bill gave citizenship to “persons of African descent born in the United States.” That language, however, was seen as too narrow because it cast doubt on birthright citizenship for all others, so the sponsors revised the wording to cover “(a)ll persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign Power.”

Some in Congress feared the bill would open the door for an influx of Chinese immigrants. Senator Edgar Cowan of Pennsylvania, for example, predicted “the day may not be very far distant when California, instead of belonging to the Indo-European race, may belong to the Mongolian…” (Mongolian or Mongol was a term often applied to the Chinese). Senator Peter G. Van Winkle of West Virginia foresaw a wave of immigrants “whose mixture with our race…could only tend to the deterioration of the mass.” Trumbull, however, felt it was only fair to make “…the child of an Asiatic…just as much a citizen as the child of a European.” In June 1866, Congress enacted the bill, known as the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

To prevent a future Congress from undoing birthright citizenship, the act’s supporters tacked it onto the proposed 14th Amendment, then pending in Congress, granting citizenship to “(a)ll persons born…in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The goal, Senator Jacob M. Howard of Michigan said, was to end “all doubt as to what persons are or are not citizens of the United States.” The “subject-to” clause, he explained, excluded children born here to foreign diplomats and the offspring of Indian tribes that Congress treated as sovereign.

Cowan again objected. “(I)s it proposed that the people of California are to remain quiescent while they are overrun by a flood of immigration of the Mongol race? Are they to be immigrated out of house and home by Chinese?” he asked. In June 1866, the House and Senate approved the 14th Amendment by the required two-third’s vote. It was ratified by the states and became law in July 1868.

The Civil Rights Act and the 14th Amendment clarified citizenship but did nothing to quell intensifying anti-Chinese animus.

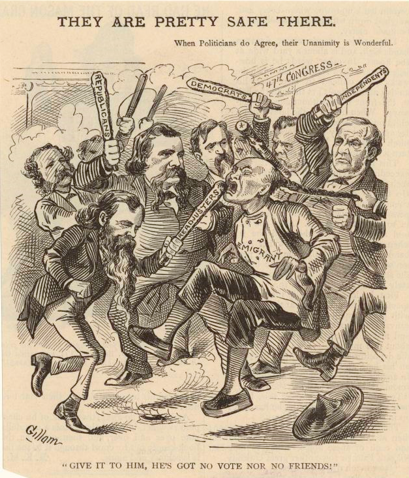

In October 1871, a mob rampaged through the Chinese section of Los Angeles, lynching and shooting. Nineteen Chinese people were killed. In San Francisco in July 1877, a three-day riot against the city’s Chinese population cost the lives of four Chinese and destroyed $500,000 worth of property. The Washington (D.C.) Star attributed the violence to “a deep and widespread feeling among both laboring and hoodlum classes against the Chinese which only lacks a favorable opportunity to break out into open hostilities.” The anti-Chinese sentiment, however, went beyond the so-called “laboring and hoodlum classes.” In an 1879 referendum, for example, 154,638 California voters opposed Chinese immigration, while only 883 supported it.

Congress, too, began to see Chinese immigration as a pressing problem. The impetus was the jump in the country’s Chinese population from 63,190 in 1870 to 105,465 in 1880. Most lived in California, and a congressional committee in 1877 called these immigrants “an indigestible mass” and concluded it was “painfully evident that the Pacific coast must in time become either American or Mongolian.” Senator James Z. George of Mississippi urged Congress to intervene to protect “the white people of the Pacific States” against “a degrading and destructive association with the inferior race now threatening to overrun them.”

In May 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the nation’s first broad restriction on immigration. It barred Chinese laborers from entering the country, prevented Chinese immigrants already here from becoming naturalized citizens and required each port’s customs collector to enforce the ban on Chinese migrants.

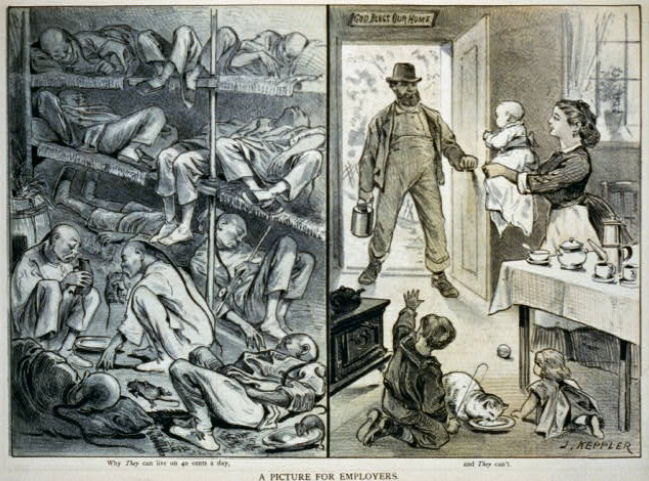

By 1890, nearly 70% of the nation’s Chinese population lived in California. Many Californians accused the Chinese of stealing their jobs and depressing the wage scale. In a pamphlet subtitled “American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism,” for example, the American Federation of Labor claimed Chinese labor “underbids all white labor and ruthlessly takes its place.”

The main objection, however, seemed to be that Chinese immigrants did not look or act like other Americans. The San Francisco Call reflected this attitude, stating that the Chinese “wear a foreign dress, speak a foreign tongue, carry on their business under foreign rules…hold themselves entirely separate and distinctive…” Chapters of the Anti-Chinese League sprang up throughout California and demanded mass deportations.

Wong’s confinement aboard ship in San Francisco Bay soon put him in a role he could never have envisioned, the focal point of the debate on Chinese immigration. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, a civic and business group, hired Thomas D. Riordan to represent Wong. Described as a man whose “genial manner attracted and made friends,” the 41-year-old Riordan had made his name as attorney for the Chinese community. He filed a habeas corpus petition in federal court in San Francisco, claiming Wong’s detention was illegal because as a citizen, he was entitled to re-enter the country. U.S. District Attorney Henry S. Foote opposed the petition.

To Riordan, the 14th Amendment was clear: if Wong was born here, he was a citizen. A contrary interpretation, he noted, would strip citizenship not just from the Chinese but from all children of foreign-born non-citizen parents. “Think of all the people in this country who have been born of parents who owed allegiance to either Great Britain, Germany, Italy or some other European power,” he argued. “Are these people to be declared not citizens?” This was a sizeable group. As of 1890, nearly 20% of the native-born U.S. population had foreign-born parents.

Attorney George D. Collins, 31, joined the case as a friend of the court, intent on barring Wong from citizenship. He saw the Chinese as “a people foreign to us in every respect” and “antagonistic to our civilization.” Considered “an able and eloquent advocate,” Collins had achieved notoriety by devising a novel legal theory that he hoped would block the children of Chinese immigrants from citizenship.

Collins insisted that even though Wong was born here, he was not a citizen because he was not subject to U.S. jurisdiction, as the 14th Amendment requires. Wong’s parents were Chinese immigrants but not American citizens, and as such, he claimed, they were still subject to the emperor of China. Under international law, a child’s status followed that of his father, so if Wong’s father was subject to Chinese jurisdiction, Collins asserted, so was his son.

Foote and Collins did not need a clever approach because, if pressed, Wong probably could not have proved he was born here. He had no birth certificate, and the three men who signed his affidavit were unlikely to have first-hand knowledge of his birth. His parents had moved back to China in 1890 and were unavailable to testify. Wong’s own affidavit was not enough because federal law treated the testimony of Chinese people as unreliable in immigration cases.

This simple approach, however, was not good enough for Collins and Foote. They wanted to build a test case to force the U.S. Supreme Court to settle the contours of birthright citizenship once and for all, so they stipulated that Wong had been born in San Francisco. Without the birthplace issue to muddy the waters, the courts would have to address the scope of the 14th Amendment’s citizenship provision.

On January 3, 1896, District Court Judge William W. Morrow did just that and declared Wong a citizen. Wong was freed on $250 bond after having been held aboard ship for nearly five months, and the government appealed to the Supreme Court.

The high court heard arguments in Washington, D.C., on March 5 and March 8, 1897. Because of a vacancy on the Court, only eight justices participated. Riordan, assisted by two other attorneys, argued for Wong, while U.S. Solicitor General Holmes Conrad spoke for the government, with Collins assisting.

The Court wrestled with the case for more than a year, and on March 28, 1898, it held by a 6-2 margin that Wong was, indeed, a citizen. Justice Horace Gray’s majority opinion reasoned that because Wong’s parents lived here and intended to stay here, they and their son were subject to U.S. jurisdiction and, thus, Wong was a birthright citizen. Gray noted that the language and intent of the 14th Amendment “irresistibly” led to the conclusion that all “children born within the territory of the United States of all other persons, of whatever race or color,” are citizens.

The decision sparked anger in California. Some feared the ruling would open the floodgates for Chinese-Americans to vote. “(T)here were warnings of the dangers to arise from the voting of the native born Chinese, but it appeared too distant to be much feared,” the Gonzalez (Calif.) Tribune noted. “Now it is come nearer…” The San Francisco Call predicted efforts would be made “to put a quietus on the ambition of these young Chino-Americans,” and the San Francisco Chronicle suggested it might be necessary “to amend the Federal Constitution and definitely limit citizenship to whites and blacks.”

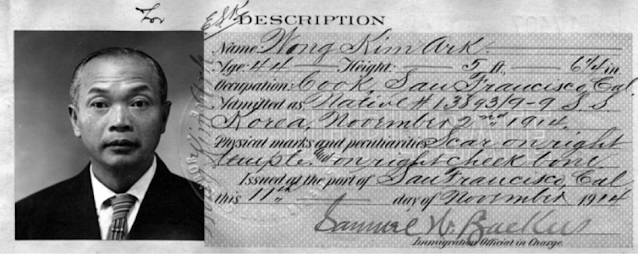

Despite the Supreme Court victory, Wong’s immigration woes were not over.

In 1901, while living in El Paso, Texas, Wong crossed the border to Juarez, Mexico. When he returned on October 29th, customs official Charles Mehan arrested him for trying to enter the country in violation of the Chinese Exclusion Act. He was freed on $300 bond, and it wasn’t until February 18, 1902 that immigration officials conceded he was the same man whose citizenship had been vouched for by the highest court in the land.

Nine years later, Wong ran afoul of the immigration authorities again when he tried to bring his son to this country.

While visiting China in 1890, Wong had married a woman, Yee Shee, and fathered a son, Wong Yook Fun, who was born there. At the time, it was not uncommon for a man of Chinese descent to have a wife and children in China while he lived and worked here. In 1910, Wong wanted to bring his son to this country for the opportunity “to be educated for whatever occupation or calling he may see fit as best for him,” he said. Under U.S. law, a foreign-born child of a citizen was also a citizen.

Immigration officials were suspicious. To evade the Chinese Exclusion Act, some Chinese men and women fraudulently claimed to be the children of U.S. citizens. They were called “paper sons” and “paper daughters.” On December 27, 1910, Luther C. Steward, acting commissioner of immigration, found Wong Yook Fun to be a “paper son” and refused to let him enter the country. He was sent back to China, never to return. In the 1920s, however, Wong’s other three foreign-born sons – Wong Yook Thue, Wong Yook Sue and Wong Yook Jim – were allowed to settle here as the children of a U.S. citizen.

Wong Kim Ark’s later life is a mystery. He made several trips to China, but after he left for China in 1931, there is no record of whether he came back or when he died.

Collins returned to the spotlight in 1905, albeit for much different reasons. In a case drawing lurid press coverage, he was charged in San Francisco with bigamy and perjury. After being convicted of the latter, he was sentenced to 14 years in prison and disbarred. He died in 1944. Riordan continued to practice law in San Francisco and died in 1905. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which had caused so much grief for Wong and others, remained in effect until 1943.

For many years, the Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court decision remained settled law, accepted as the final word on birthright citizenship. In the last decade, however, citizenship has once again become the flash point of intense public debate.

This time, the target is undocumented migrants, also called illegal aliens. These are people, mostly from Mexico, Central America or South America, who have entered the country illegally, stayed after their permission to be here has expired or violated the conditions of their entry. These immigrants, the federal government claims, “present significant threats to national security and public safety” and have “cost taxpayers billions of dollars at the Federal, State, and local levels.”

To deter unlawful immigration, the government has zeroed in on birthright citizenship, claiming it provides “strong incentives for illegal immigration” and grants citizenship “to persons who lack meaningful ties to the country.” By Executive Order dated January 20, 2025, President Trump has sought to end citizenship for the offspring of undocumented migrants.

The government insists this executive order comports with the 14th Amendment, arguing that birthright citizenship covers only the children of immigrant parents who have the right to stay here permanently, which undocumented migrants do not. Opponents strenuously disagree, seeing no legal basis to single out the offspring of undocumented immigrants. It seems inevitable, therefore, that the Supreme Court will soon be called upon once again to decide the vexing question of just who is entitled to be called an American.