John Hay’s ringing phrase helped nominate T. R., but it covered an embarrassing secret that remained concealed for thirty years.

-

August 1959

Volume10Issue5 -

Summer 2025

Volume70Issue3

On a scented Mediterranean May evening in 1904, Mr. Ion Perdicaris, an elderly, wealthy American, was dining with his family on the vine-covered terrace of the Place of Nightingales, his summer villa in the hills above Tangier. Besides a tame demoiselle crane and two monkeys who ate orange blossoms, the family included Mrs. Perdicaris; her son by a former marriage, Cromwell Oliver Varley, who (though wearing a great name backward) was a British subject; and Mrs. Varley. Suddenly a cacophony of shrieks, commands, and barking of dogs burst from the servants’ quarters at the rear. Assuming the uproar to be a further episode in the chronic feud between their German housekeeper and their French-Zouave chef, the family headed for the servants’ hall to frustrate mayhem. They ran into the butler flying madly past them, pursued by a number of armed Moors whom at first they took to be their own household guards. Astonishingly, these persons fell upon the two gentlemen, bound them, clubbed two of the servants with their gunstocks, knocked Mrs. Varlcy to the floor, drew a knife against Varley’s throat when he struggled toward his wife, dragged off the housekeeper who was screaming into the telephone “Robbers! Help!,” cut the wire, and shoved their captives out of the house with guns pressed in their backs.

Waiting at the villa’s gate was a handsome, blackbearded Moor with blazing eyes and a Greek profile, who, raising his arm in a theatrical gesture, announced in the tones of Henry Irving playing King Lear, “I am the Raisuli!” Awed, Perdicaris and Varley knew they stood face to face with the renowned Berber chief, lord of the Rif and last of the Barbary pirates, whose personal struggle for power against his nominal overlord, the Sultan of Morocco, periodically erupted over Tangier in raids, rapine, and interesting varieties of pillage. He now ordered his prisoners hoisted onto their horses and, thoughtfully stealing Perdicaris’ best mount, a black stallion, for himself, fired the signal for departure. The bandit cavalcade, in a mad confusion of shouts, shots, rearing horses, and trampled bodies, scrambled off down the rocky hillside, avoiding the road, and disappeared into the night in the general direction of the Atlas Mountains.

A moment later, Samuel R. Gummere, United States consul general, was interrupted at dinner by the telephone operator who passed on the alarm from the villa. After a hasty visit to the scene of the outrage, where he ascertained the facts, assuaged the hysterical ladies, and posted guards, Gummere returned to confer with his colleague, Sir Arthur Nicolson, the British minister. Both envoys saw alarming prospects of danger to all foreigners in Morocco as the result of Raisuli’s latest pounce.

Morocco’s already anarchic affairs had just been thrown into even greater turmoil by the month-old Anglo-French entente. Under this arrangement, England, in exchange for a free hand in Egypt, had given France a free hand in Morocco, much to the annoyance of all Moroccans. The Sultan, AbduI-Aziz, was a well-meaning but helpless young man uneasily balanced on the shaky throne of the last independent Moslem country west of Constantinople. He was a puppet of a corrupt clique headed by Ben Sliman, the able and wicked old grand vizier. To keep his young master harmlessly occupied while he kept the reins, not to mention the funds, of government in his own hands, Ben Sliman taught the Sultan a taste for, and indulged him in all manner of, extravagant luxuries of foreign manufacture. But Abdul-Aziz’s tastes got out of bounds. Not content with innumerable bicycles, 600 cameras, 25 grand pianos, and a gold automobile (though there were no roads), he wanted Western reforms to go with them. These, requiring foreign loans, willingly supplied by the French, opened the age-old avenue of foreign penetration. The Sultan’s Western tastes and Western debts roused resentment among his fanatic tribes. Rebellions and risings had kept the country in strife for some years past, and European rivalries complicated the chaos. France, already deep in Algeria, was pressing against Morocco’s borders. Spain had special interests along the Mediterranean coast. Germany was eyeing Morocco for commercial opportunities and as a convenient site for naval coaling bases. England, eyeing Germany, determined to patch up old feuds with France and had just signed the entente in April. The Moroccan government, embittered by what it considered England’s betrayal, hating France, harassed by rebellion, tottering on the brink of bankruptcy, had yet one more scourge to suffer. This was the Sherif Mulai Ahmed ibn-Muhammed er Raisuli, who now seized his moment. To show up the Sultan’s weakness, proportionately increase his own prestige, and extract political concessions as ransom, he kidnapped the prominent American resident Mr. Perdicaris.

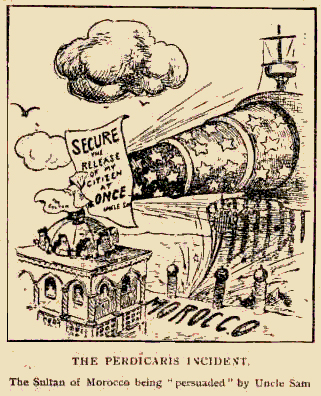

“Situation serious” telegraphed Gummere to the State Department on May 19. “Request man-of-war to enforce demands.” No request could have been more relished by President Theodore Roosevelt. Not yet 46, bursting with vigor, he delighted to make the Navy the vehicle of his exuberant view of national policy. At the moment of Perdicaris’ kidnapping he faced, within the next month, a nominating convention that could give him what he most coveted: a chance to be elected President “in my own right.” Although there was no possibility of the convention’s nominating anyone else, Roosevelt knew it would be dominated by professional politicians and standpatters who were unanimous in their distaste for “that damned cowboy,” as their late revered leader, Mark Hanna, had called him. The prospect did not intimidate Roosevelt. “The President,” said his great friend, Ambassador Jean Jules Jusserand of France, “is in his best mood. He is always in his best mood.” The President promptly ordered to Morocco not one warship, but four, the entire South Atlantic Squadron—due shortly to coal at Tenerife in the Canaries, where it could receive its orders to proceed at once to Tangier. Roosevelt knew it to be under the command of a man exactly suited to the circumstances, Admiral French Ensor Chadwick, a decorated veteran of the Battle of Santiago and, like Roosevelt, an ardent disciple of Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan’s strenuous theories of naval instrumentality.

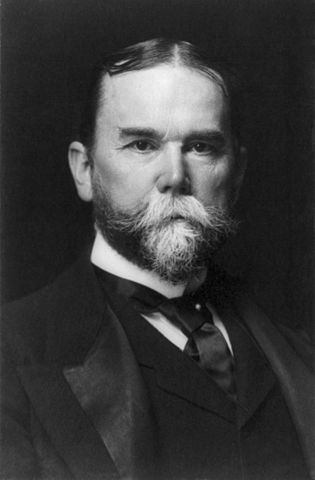

Roosevelt’s second in foreign policy was that melancholy and cultivated gentleman and wit, John Hay, who had been Lincoln’s private secretary, wanted only to be a poet, and was, often to his own disgust, Secretary of State. On the day of the kidnapping he was absent, delivering a speech at the St. Louis Fair. His subordinates, however, recognized Gummere, who was senior diplomatic officer in Tangier in the absence of any American minister and had six years’ experience at that post, as a man to be listened to. The victim, Perdicaris, was also a man of some repute, whose name was known in the State Department through a public crusade he had waged back in 1886–87 against certain diplomatic abuses practiced in Tangier. His associate in that battle had been Gummere himself, then a junior member of the foreign service and Perdicaris’ friend and fellow-townsman from Trenton, New Jersey.

“Warships will be sent to Tangier as soon as possible,” the department wired Gummere. “May be three or four days before one arrives.” Ships in the plural was gratifying, but the promised delay was not. Gummere feared the chances of rescuing Perdicaris and Varley were slim. Nicolson gloomily concurred. They agreed that the only hope was to insist upon the Sultan’s government giving in to whatever demands Raisuli might make as his price for release of his prisoners. Most inconveniently the government was split, its foreign minister, Mohammed Torres, being resident at Tangier where the foreign legations were located, while the Sultan, grand vizier, and court were at Fez, which was three days’ journey by camel or mule into the interior. Gummere and Nicolson told Mohammed Torres they expected immediate acquiescence to Raisuli’s demands, whatever these might prove to be, and dispatched their vice-consuls to Fez to impress the same view urgently upon the Sultan.

The French minister, St. René Taillandier, did likewise, but, since the Anglo-French entente was still too new to have erased old jealousies, he acted throughout the affair more or less independently. France had her own reasons for wishing to see Perdicaris and Varley safely restored as quickly as possible. Their abduction had put the foreign colony in an uproar that would soon become panic if they were not rescued. The approach of the American fleet would seem to require equal action by France as the paramount power in the area, but France was anxious to avoid a display of force. She was “very nervous,” Admiral Chadwick wrote later, at the prospect of taking over “the most fanatic and troublesome eight or ten millions in the world”; she had hoped to begin her penetration as unobtrusively as possible without stirring up Moroccan feelings any further against her. Hurriedly, St. René Taillandier sent off two noble mediators to Raisuli; they were the young brother sherifs of the Wazan family, who occupied a sort of religious primacy among sherifs and whom France found it worthwhile to subsidize as her protégés.

While awaiting word from the mediators, Gummere and Nicolson anxiously conferred with an old Moroccan hand, Walter B. Harris, correspondent of the London Times, who had himself been kidnapped by Raisuli the year before. Raisuli had used that occasion to force the Bashaw, or local governor, of Tangier to call off a punitive expedition sent against him. This Bashaw, who played Sheriff of Nottingham to Raisuli’s Robin Hood, was Raisuli’s foster brother and chief hate; the two had carried on a feud ever since the Bashaw had tricked Raisuli into prison eight years before. The Bashaw sent troops to harass and tax Raisuli’s tribes and burn his villages; at intervals he dispatched emissaries instructed to lure his enemy to parley. Raisuli ambushed and slaughtered the troops and returned the emissaries—or parts of them. The head of one was delivered in a basket of melons. Another came back in one piece, soaked in oil and set on fire. The eyes of another had been burned out with hot copper coins.

Despite such grisly tactics, Harris reported to Gummere and Nicolson, his late captor was a stimulating conversationalist who discoursed on philosophy in the accents of the Moorish aristocracy and denied interest in ransom for its own sake. “Men think I care about money,” he had told Harris, “but, I tell you, it is only useful in politics.” He had freed Harris in return for the release of his own partisans from government prisons, but since then more of these had been captured. This time Raisuli’s demands would be larger and the Sultan less inclined to concede them. Sir Arthur recalled that on the last occasion Mohammed Torres had “behaved like an old brute” and shrugged off Harris’ fate as being in the hands of the Lord, when in fact, as Nicolson had pointed out to him, Harris was “in the hands of a devil.” Sir Arthur had suffered acutely. “I boil,” he confessed, “to have to humiliate myself and negotiate with these miserable brigands within three hours of Gibraltar.” Gummere thought sadly of his poor friend Perdicaris. “I cannot conceal from myself and the Department,” he wrote that night, “that only by extremely delicate negotiations can we hope to escape from the most terrible consequences.”

Back in America, the Perdicaris case provided a welcome sensation to compete in the headlines with the faraway fortunes of the Russo-Japanese War. A rich old gentleman held for ransom by a cruel but romantic brigand, the American Navy steaming to the rescue—here was personal drama more immediate than the complicated rattle of unpronounceable generals battling over unintelligible terrain. The President’s instant and energetic action on behalf of a single citizen fallen among thieves in a foreign land made Perdicaris a symbol of America’s new role on the world stage.

The man himself was oddly cast for the part. Digging up all available information, the press discovered that he was the son of Gregory Perdicaris, a native of Greece who had become a naturalized American, taught Greek at Harvard, married a lady of property from South Carolina, made a fortune in illuminating gas, settled in Trenton, New Jersey, and served for a time as United States consul in his native land. The son entered Harvard with the class of 1860 but left in his sophomore year to study abroad. For a young man who was 21 at the opening of the Civil War, his history during the next few years was strangely obscure, a fact which the press ascribed to a conflict between his father, a Union sympathizer, and his mother, an ardent Confederate. Subsequently the son lived peripatetically in England, Morocco, and Trenton as a dilettante of literature and the arts, producing magazine articles, a verse play, and a painting called Tent Life. He had built the now famous Villa Aidonia (otherwise Place of Nightingales) in 1877, and settled permanently in Tangier in 1884. There he lavishly entertained English and American friends among Oriental rugs, damasks, rare porcelains, and Moorish attendants in scarlet knee-pants and gold-embroidered jackets. He was known as a benefactor of the Moors and as a supporter of a private philanthropy that endowed Tangier with a modern sanitation system. He rode a splendid Arab steed—followed by his wife on a white mule—produced an occasional literary exercise or allegorical painting, and enjoyed an Edwardian gentleman’s life amid elegant bric-a-brac.

A new telegram from the State Department desired Gummere to urge “energetic” efforts by the authorities to rescue Perdicaris and punish his captor—“if practicable,” it added, with a bow to realities. Gummere replied that this was the difficulty: Raisuli, among his native crags, was immune from reprisal. The Sultan, who had a tatterdemalion army of some 2,000, had been trying vainly to capture him for years. Gummere became quite agitated. United action by the powers was necessary to prevent further abductions of Christians; Morocco was “fast drifting into a state of complete anarchy,” the Sultan and his advisers were weak or worse, governors were corrupt, and very soon “neither life nor property will be safe.”

On May 22 the younger Wazan returned with Raisuli’s terms. They demanded everything: prompt withdrawal of government troops from the Rif; dismissal ol the Bashaw of Tangier; arrest and imprisonment of certain officials who had harmed Raisuli in the past; release of Raisuli’s partisans from prison; payment of an indemnity of $70,000 to be imposed personally upon the Bashaw, whose property must be sold to raise the amount; appointment of Raisuli as governor of two districts around Tangier that should be relieved of taxes and ceded to him absolutely; and, finally, safe-conduct for all Raisuli’s tribesmen to come and go freely in the towns and markets.

Gummere was horrified; Mohammed Torres declared his government would never consent. Meanwhile European residents, increasingly agitated, were flocking in from outlying estates, voicing indignant protests, petitioning for a police force, guards, and gunboats. The local Moors, stimulated by Raisuli’s audacity, were showing an aggressive mood. Gummere, scanning the horizon for Admiral Chadwick’s smokestacks, hourly expected an outbreak. Situation “not reassuring,” he wired; progress of talks “most unsatisfactory”; warship “anxiously awaited. Can it be hastened?”

The American public awaited Chadwick’s arrival as eagerly as Gummere. Excitement rose when the press reported that Admiral Theodore F. Jewell, in command of the European Squadron, three days’ sail behind Chadwick, would be ordered to reinforce him if the emergency continued.

Tangier received further word from the sherifs of Wazan that Raisuli had not only absolutely declined to abate his demands but had added an even more impossible condition: a British and American guarantee of fulfillment of the terms by the Moroccan government.

Knowing his government could not make itself responsible for the performance or non-performance of promises by another government, Gummere despairingly cabled the terms to Washington. As soon as he saw them, Roosevelt sent “in a hurry” for Secretary Hay (who had meanwhile returned to the capital). “I told him,” wrote Hay that night in his diary, “I considered the demands of the outlaw Raisuli preposterous and the proposed guarantee of them by us and by England impossible of fulfillment.” Roosevelt agreed. Two measures were decided upon and carried out within the hour: Admiral Jewell’s squadron was ordered to reinforce Chadwick at Tangier, and France was officially requested to lend her good offices. (By recognizing France’s special status in Morocco, this step, consciously taken, was of international significance in the train of crises that was to lead through Algeciras and Agadir to 1914.) Roosevelt and Hay felt they had done their utmost. “I hope they may not murder Mr. Perdicaris,” recorded Hay none too hopefully, “but a nation cannot degrade itself to prevent ill-treatment of a citizen.”

An uninhibited press told the public that in response to Raisuli’s “insulting” ultimatum, “all available naval forces” in European waters were being ordered to the spot. Inspired by memory of U.S. troops chasing Aguinaldo in the Philippines, the press suggested that “if other means fail” marines could make a forced march into the interior to “bring the outlaw to book for his crimes.” Such talk terrified Gummere, who knew that leathernecks would have as much chance against Berbers in the Rif as General Braddock’s redcoats against Indians in the Alleghenies; and besides, the first marine ashore would simply provoke Raisuli to kill his prisoners.

See more: "Funston Captures Aguinaldo," by William F. Zornow, February 1958, Volume 9, Issue 2

On May 29 the elder Wazan brought word that Raisuli threatened to do just that if all his demands were not met in two days. Two days! This was the twentieth century, but as far as communications with Fez were concerned it might as well have been the time of the Crusades. Nevertheless, Gummere and Nicolson sent couriers to meet their vice-consuls at Fez (or intercept them if they had already left) with orders to demand a new audience with the Sultan and obtain his acceptance of Raisuli’s terms.

At five thirty next morning a gray shape slid into the harbor. Gummere, awakened from a troubled sleep, heard the welcome news that Admiral Chadwick had arrived at last aboard his flagship, the Brooklyn. Relieved, yet worried that the military mind might display more valor than discretion, he hurried down to confer with the Admiral. In him he found a crisp and incisive officer whose quick intelligence grasped the situation at once. Chadwick agreed that the point at which to apply pressure was Mohammed Torres. Although up in the hills the brigand’s patience might be wearing thin, the niceties of diplomatic protocol, plus the extra flourishes required by Moslem practice, called for an exchange of courtesy calls before business could be done. Admiral and consul proceeded at once to wait upon the foreign minister, who returned the call upon the flagship that afternoon. It was a sight to see, Chadwick wrote to Hay, his royal progress through the streets, “a mass of beautiful white wool draperies, his old calves bare and his feet naked but for his yellow slippers,” while “these wild fellows stoop and kiss his shoulder as he goes by.”

Mohammed Torres was greeted by a salute from the flagship’s guns and a review of the squadron’s other three ships, which had just arrived. Unimpressed by these attentions, he continued to reject Raisuli’s terms. “Situation critical,” reported Chadwick.

The situation was even more critical in Washington. On June 1, an extraordinary letter reached the State Department. Its writer, one A. H. Slocumb, a cotton broker of Fayetteville, North Carolina, said he had read with interest about the Perdicaris case and then, without warning, asked a startling question, “But is Perdicaris an American?” In the winter of 1863, Mr. Slocumb went on to say, he had been in Athens, and Perdicaris had come there “for the express purpose, as he stated, to become naturalized as a Greek citizen.” His object, he had said, was to prevent confiscation by the Confederacy of some valuable property in South Carolina inherited from his mother. Mr. Slocumb could not be sure whether Perdicaris had since resumed American citizenship, but he was “positive” that Perdicaris had become a Greek subject forty years before, and he suggested that the Athens records would bear out his statement.

What blushes reddened official faces we can only imagine. Hay’s diary for June 1 records that the President sent for him and Secretary of the Navy Moody “for a few words about Perdicaris,” but, maddeningly discreet, Hay wrote no more. A pregnant silence of three days ensues between the Slocumb letter and the next document in the case. On June 4 the State Department queried our minister in Athens, John B. Jackson, asking him to investigate the charge—“important if true,” added the department, facing bravely into the wind. Although Slocumb had mentioned only 1863, the telegram to Jackson asked him to search the records for the two previous years as well; apparently the department had been making frenzied inquiries of its own during the interval. On June 7 Jackson telegraphed in reply that a person named Ion Perdicaris, described as an artist, unmarried, aged 22, had indeed been naturalized as a Greek on March 19, 1862.

Posterity will never know what Roosevelt or Hay thought or said at this moment, because the archives are empty of evidence. But neither the strenuous President nor the suave Secretary of State was a man easily rattled. The game must be played out. Already Admiral Jewell’s squadron of three cruisers had arrived to reinforce Chadwick, making a total of seven American warships at Tangier. America’s fleet, flag, and honor were committed. Wheels had been set turning in foreign capitals. Hay had requested the good offices of France. The French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé, was himself bringing pressure. A British warship, the Prince of Wales, had also come to Tangier. Spain wanted to know if the United States was wedging into Morocco.

And just at this juncture the Sultan’s government, succumbing to French pressure, ordered Mohammed Torres to accede to all Raisuli’s demands. Four days later, on June 12, a French loan to the government of Morocco was signed at Fez in the amount of 62.5 million francs, secured by the customs of all Moroccan ports. It seemed hardly a tactful moment to reveal the fraudulent claim of Mr. Perdicaris.

He was not yet out of danger, for Raisuli refused to release him before all the demands were actually met, and the authorities were proving evasive. Washington was trapped. Impossible to reveal Perdicaris’ status now; equally impossible to withdraw the fleet and leave him, whom the world still supposed to be an American, at the brigand’s mercy.

During the next few days suspense was kept taut by a stream of telegrams from Gummere and Chadwick reporting one impasse after another in the negotiations with Raisuli. When the Sultan balked at meeting all the terms in advance of the release, Raisuli merely rasied his ante, demanding that four districts instead of two be ceded to him and returning to the idea of an Anglo-American guarantee. “You see there is no end to the insolence of this blackguard,” wrote Hay in a note to the President on June 15; Roosevelt, replying the same day, agreed that we had gone “as far as we possibly can go for Perdicaris” and could now only “demand the death of those that harm him if he is harmed.” He dashed off an alarming postscript: “I think it would be well to enter into negotiations with England and France looking to the possibility of an expedition to punish the brigands if Gummere’s statement as to the impotence of the Sultan is true.”

No further action was taken in pursuit of this proposal because Gummere’s telegrams now grew cautiously hopeful; on the nineteenth he wired that all arrangements had been settled for the release to take place on the twenty-first. But on the twentieth all was off. Raisuli suspected the good faith of the government, a sentiment which Gummere and Chadwick evidently shared, for they blamed the delay on “intrigue of authorities here.” Finally the exasperated Gummere telegraphed on the twenty-first that the United States position was “becoming humiliating.” He asked to be empowered to deliver an ultimatum to the Moroccan government claiming an indemnity for each day’s further delay, backed by a threat to land marines and seize the customs as security. Admiral Chadwick concurred in a separate telegram.

June 21 was the day the Republican National Convention met in Chicago. “There is a great deal of sullen grumbling,” Roosevelt wrote that day to his son Kermit, “but they don’t dare oppose me for the nomination.… How the election will turn out no one can tell.” If a poll of Republican party leaders had been taken at any time during the past year, one newspaper estimated, it would have shown a majority opposed to Roosevelt’s nomination. But the country agreed with Viscount Bryce, who said Roosevelt was the greatest President since Washington (prompting a Roosevelt friend to recall Whistler’s remark when told he was the greatest painter since Velázquez: “Why drag in Velázquez?”). The country wanted Teddy and, however distasteful that fact was, the politicians saw the handwriting on the bandwagon. On the death of Mark Hanna four months before, active opposition had collapsed, and the disgruntled leaders were now arriving in Chicago prepared to register the inevitable as ungraciously as possible.

They were the more sullen because Roosevelt and his strategists, preparing against any possible slip-up, had so steam-rollered and stage-managed the proceedings ahead of time that there was nothing left for the delegates to do. No scurrying, no back-room bargaining, no fights, no trades, no smoke-filled deals. Harper’s Weekly reported an Alabama delegate’s summation: “There ain’t nobody who can do nothin’ ” and added: “It is not a Republican Convention, it is no kind of a convention; it is a roosevelt.”

The resulting listlessness and pervading dullness were unfortunate. Although Elihu Root, Henry Cabot Lodge, and other hand-picked Roosevelt choices filled the key posts, most of the delegates and party professionals did not make even a pretense of enthusiasm. The ostentatious coldness of the delegation from New York, Roosevelt’s home state, was such that one reporter predicted they would all go home with pneumonia. There were no bands, no parades, and for the first time in forty years there were hundreds of empty seats.

Roosevelt knew he had the nomination in his pocket, but all his life, like Lincoln, he had a haunting fear of being defeated in elections. He was worried lest the dislike and distrust of him so openly exhibited at Chicago should gather volume and explode at the ballot box. Something was needed to prick the sulks and dispel the gloom of the convention before it made a lasting impression upon the public.

At this moment came Gummere’s plea for an ultimatum. Again we have no record of what went on in high councils, but President and Secretary must have agreed upon their historic answer within a matter of hours. The only relevant piece of evidence is a verbal statement made to Hay’s biographer, the late Tyler Dennett, by Gaillard Hunt, who was chief of the State Department’s Citizenship Bureau during the Perdicaris affair. Hunt said he showed the correspondence about Perdicaris’ citizenship to Hay, who told him to show it to the President; on seeing it, the President decided to overlook the difficulty and instructed Hunt to tell Hay to send the telegram anyway, at once. No date is given for this performance, so one is left with the implication that Roosevelt was not informed of the facts until this last moment—a supposition which the present writer finds improbable.

When Roosevelt made up his mind to accomplish an objective he did not worry too much about legality of method. Before any unusual procedure he would ask an opinion from his Attorney General, Philander Knox, but Knox rather admired Roosevelt’s way of overriding his advice. Once, when asked for his opinion, he replied, “Ah, Mr. President, why have such a beautiful action marred by any taint of legality?” Another close adviser, Admiral Mahan, when asked by Roosevelt how to solve the political problem of annexing the Hawaiian Islands, answered, “Do nothing unrighteous but … take the islands first and solve afterward.” It may be that the problem of Perdicaris seemed susceptible of the same treatment.

The opportunity was irresistible. Every newspaperman who ever knew him testified to Roosevelt’s extraordinary sense of news value, to his ability to create news, to dramatize himself to the public. He had a genius for it. “Consciously or unconsciously,” said the journalist Isaac Marcosson, “he was the master press agent of all time.” The risk, of course, was great, for it would be acutely embarrassing if the facts leaked out during the coming campaign. It may have been the risk itself that tempted Roosevelt, for he loved a prank and loved danger for its own sake; if he could combine danger with what William Allen White called a “frolicking intrigue,” his happiness was complete.

Next day, June 22, the memorable telegram, “This Government wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead,” flashed across the Atlantic cable over Hay’s signature and was simultaneously given to the press at home. It was not an ultimatum, because Hay deliberately deprived it of meaningfulness by adding to Gummere, “Do not land marines or seize customs without Department’s specific instructions.” But this sentence was not allowed to spoil the effect: it was withheld from the press.

At Chicago, Uncle Joe Cannon, the salty perennial Speaker of the House, who was convention chairman, rapped with his gavel and read the telegram. The convention was electrified. Delegates sprang upon their chairs and hurrahed. Flags and handkerchiefs waved. Despite Hay’s signature, everyone saw the Roosevelt teeth, cliche of a hundred cartoons, gleaming whitely behind it. “Magnificent, magnificent!” pronounced Senator Depew. “The people want an administration that will stand by its citizens, even if it takes the fleet to do it,” said Representative Dwight of New York, expressing the essence of popular feeling. “Roosevelt and Hay know what they are doing,” said a Kansas delegate. “Our people like courage. We’ll stand for anything those two men do.” “Good hot stuff and echoes my sentiments,” said another delegate. The genius of its timing and phrasing, wrote a reporter, “gave the candidate the maximum benefit of the thrill that was needed.” Although the public was inclined to credit authorship to Roosevelt, the Baltimore Sun pointed out that Mr. Hay too knew how to make the eagle scream when he wanted to. Hay’s diary agreed. “My telegram to Gummere,” he noted comfortably the day afterward, “had an uncalled for success. It is curious how a concise impropriety hits the public.”

After nominating Roosevelt by acclamation, the convention departed in an exhilarated mood. In Morocco a settlement had been reached before receipt of the telegram. Raisuli was ready at last to return his captives. Mounted on a “great, grey charger,” he personally escorted Perdicaris and Varley on the ride down from the mountains, pointing out on the way the admirable effect of pink and violet shadows cast by the rising sun on the rocks. They met the ransom party, with thirty pack mules bearing boxes of Spanish silver dollars, halfway down. Payment was made and prisoners exchanged, and Perdicaris took leave, as he afterward wrote, of “one of the most interesting and kindly-hearted native gentlemen” he had ever known, whose “singular gentleness and courtesy … quite endeared him to us.” At nightfall, as he rode into Tangier and saw the signal lights of the American warships twinkling the news of his release, Perdicaris was overcome with patriotic emotion at “such proof of his country’s solicitude for its citizens and for the honor of its flag” Few indeed are the Americans, he wrote to Gummere in a masterpiece of understatement, “who can have appreciated as keenly as I did then what the presence of our Flag in foreign waters meant at such a moment and in such circumstances.”

Only afterward, when it was all over, did the State Department inform Gummere how keen indeed was Perdicaris’ cause for appreciation. “Overwhelmed with amazement” and highly indignant, Gummere extracted from Perdicaris a full, written confession of his forty-year-old secret. He admitted that he had never in ensuing years taken steps to resume American citizenship because, as he ingenuously explained, having been born an American, he disliked the idea of having to become naturalized, and so, “I continued to consider myself an American citizen.” Since Perdicaris perfectly understood that the American government was in no position to take action against him, his letter made no great pretension of remorse.

Perdicaris retired to England for his remaining years. Raisuli duly became governor of the Tangier districts in place of the falsehearted Bashaw. The French, in view of recent disorders, acquired the right to police Morocco (provoking the Kaiser’s notorious descent upon Tangier). The Sultan, weakened and humiliated by Raisuli’s triumph, was shortly dethroned by a brother. Gummere was officially congratulated and subsequently appointed minister to Morocco and American delegate to the Algeciras Conference. Sir Arthur Nicolson took “a long leave of absence,” the Wazan brothers received handsomely decorated Winchester rifles with suitable inscriptions from Mr. Roosevelt, Hay received the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor, and Roosevelt was elected in November by the largest popular majority ever before given to a presidential candidate.

“As to Paregoric or is it Pericarditis,” wrote Hay to Assistant Secretary Adee on September 3, “it is a bad business. We must keep it excessively confidential for the present.” They succeeded. Officials in the know held their breath during the campaign, but no hint leaked out either then or during the remaining year of Hay’s lifetime or during Roosevelt’s lifetime. As a result of the episode, Roosevelt’s administration proposed a new citizenship law which was introduced in Congress in 1905 and enacted in 1907, but the name of the errant gentleman who inspired it was never mentioned during the debates. The truth about Perdicaris remained unknown to the public until 1933, when Tyler Dennett gave it away—in one paragraph in his biography of John Hay.