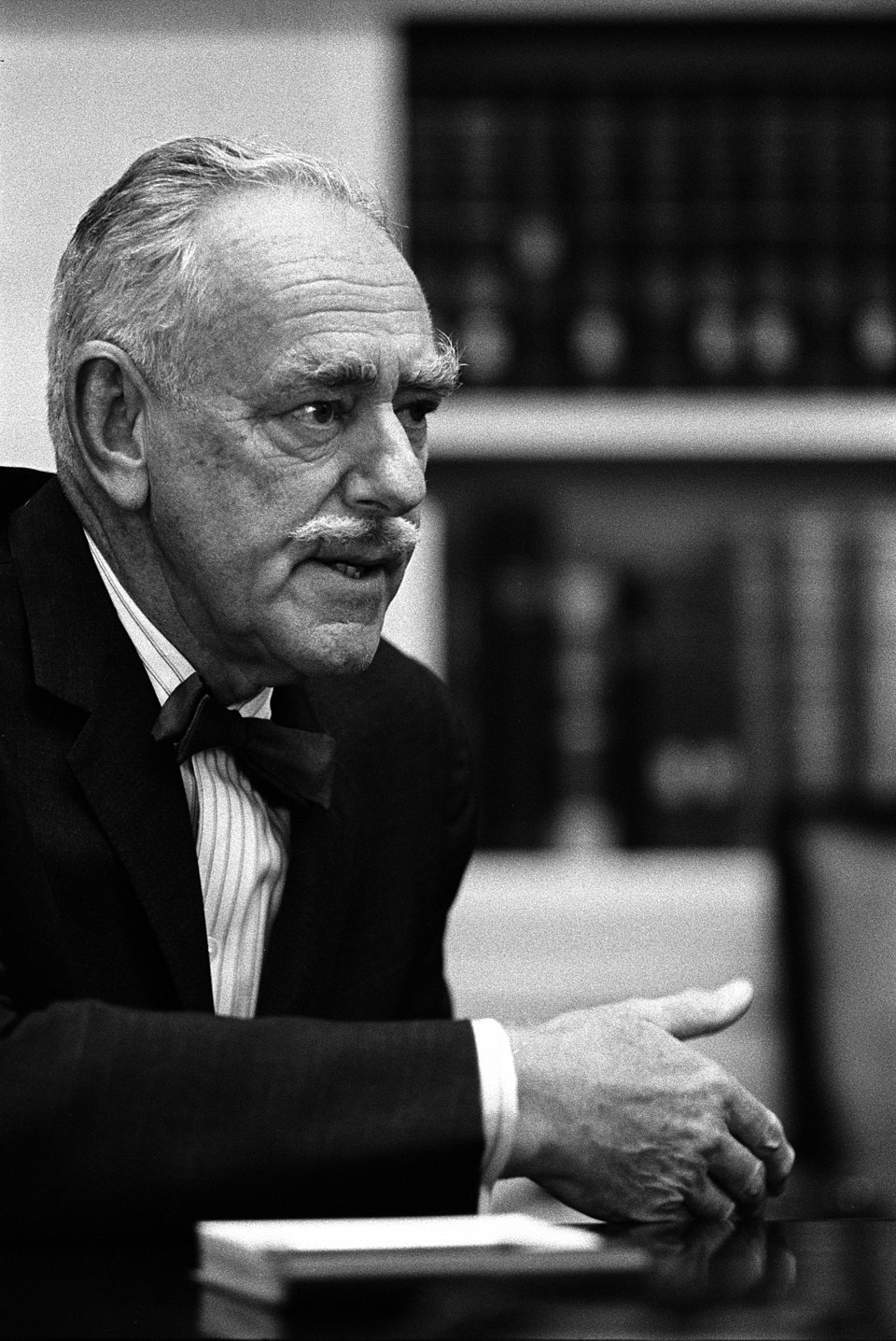

Our former Secretary of State recalls his service fifty years ago in the Connecticut National Guard—asthmatic horses, a ubiquitous major, and a memorable shooting practice.

-

Februrary 1968

Volume19Issue2 -

Summer 2025

Volume70Issue3

The calendar has it that these events occurred fifty years ago last summer. It is hardly more credible than that a thousand ages can be like an evening gone. But as President Lincoln said, “we cannot escape history.”

Nineteen sixteen was the year of the Wilhelmstrasse’s amazingly successful plot to distract President Wilson’s attention from the war in Europe by involving him with Mexico, of General “Black Jack” Pershing’s invasion of Mexico in “hot pursuit” of Pancho Villa, after that worthy had staged a raid across the Rio Grande on Columbus, New Mexico. Poor General Pershing never caught up with Villa.

But President Wilson caught up with the realization that the United States had no army. Improvising, he called out the National Guard and mustered it into the federal service. This is where I came in. Having finished the first year of law school and being without plans for the summer, I was easy prey for the press gang in the form of friends in the so-called Yale Battery, Battery D of the Connecticut National Guard’s Regiment of Field Artillery. In no time I found myself that lowly form of military life, a private and “driver” in the old horse-drawn field artillery. Garbed in a hilariously ill-fitting uniform and Stetson hat with its red cord, I made my small contribution to the gloriously unorganized confusion of our journey from New Haven to training camp at Tobyhanna in the Pocono hills of Pennsylvania.

None of our batteries had ever owned any horses. Those used in the evening drills in New Haven had been moonlighting, supplementing a more mundane daytime existence as brewery and dray horses. We would get our horses, so we were told, at Tobyhanna. They would come to us from the West—an interesting thought, this. Would we be, we wondered, the first bipeds they had ever seen? Our imagination was far inferior to the reality.

The first disillusion came on arrival. It was with mankind. We had been preceded by a New Jersey regiment which had, quite naturally, appropriated the best sites and everything movable. Our relations with them soon resembled those between colonial contingents in the Continental Army, meaning that had Hessians been handy, we should have preferred them.

Then came the horses. Those assigned to the New Jersey regiment arrived first. Words sink into pallid inadequacy. Our first impressions were gay: a vast panoramic cartoon of our enemy campmates in side-splitting trouble. Blithe horse-spirits from the Great Plains seemed to be enjoying a gymnastic festival, with inanimate human forms scattered around them. But the comedy was not to last.

Our horses emerged from their boxcars strangely docile. Only occasionally would an eye roll and heels fly or teeth bare in attempted mayhem or murder. No more was the landscape gay with mad scenes of separating centaurs. Over the whole camp a pall settled, broken only by asthmatic wheezes and horse coughs. Stable sergeants and veterinary officers hurried about with worried faces. The wretched horses had caught cold in the chill night mountain air, so different from that of their warm, free prairies. The colds had become pneumonia and contagious.

Then they began to die. One has no idea how large an animal a horse is until faced with the disposal of a dead one, and in the Poconos, where solid rock lies barely two feet under the surf ace I It was no illusion, to those whose picks drew only sparks, that the bodies of the deceased grew faster than their graves. Soon we were all pleading with the sufferers to be of good heart, not to give up the battle for life; we put slings under them to keep them on their feet; tenderly gave them the veterinarians’ doses; manned round-the-clock watches at the stables.

At just this time, far off in the higher echelons of the Army, some keen leader of men decided to raise the morale of the troops by inspecting them. The choice fell on Major General Leonard Wood, late a physician and Teddy Roosevelt’s C.O. in the Rough Riders, then commanding the Eastern Department of the Army and soon to be Governor General of the Philippines and a presidential aspirant. At that time not even Alexander the Great would have impressed us, much less imbued us with martial spirit. We were sunk too deep in the horse-undertaking business.

A friend was doing midnight-to-four sentry duty at our stables. Lanterns bobbed and boots slid on stone as a party approached. Tearing himself away from the nuances of horse breathing, he shouted “Halt! Who goes there?” Back came the ominous answer, “The Commanding General of the Eastern Department.” Rapidly exhausting his knowledge of military repartee, my friend ordered, “Advance to be recognized.” General Wood stepped into the lamplight. The sentry did not know him from the mayor of Philadelphia, but the stars on his shoulders were enough, and, anyway, he had run out of small talk. He managed a snappy salute and the word “sir!” which seemed safe enough.

General Wood took over. His examination brought out that the sentry was guarding the battery’s stable, or part of it, and that the stable was, not surprisingly, inhabited by horses. He then sought to probe the vaunted initiative of the American soldier. “What would you do,” he asked, “if, while you were on duty, one of these horses was taken sick?” For a moment the enormity of this question flooded my friend’s mind, submerging all consciousness of military protocol. When he could speak, the outrage of it burst through. “Jesus, General, they’re all sick!” Like Bret Harte’s Ah Sin, when the ace fell out of his sleeve in the poker game, “subsequent proceedings interested him no more.”

At the height of the horse crisis I was ordered to report to the Captain’s tent. General consensus recognized Captain Carroll Hincks as a good guy. A few years ahead of us at Yale, he had just begun to practice law in New Haven. He did his best to be a good soldier and a good battery commander. To say that his natural gifts lay in his own profession is no disparagement, since he was destined to become a highly respected federal judge, first on the district bench and later on the court of appeals.

The Captain began—truth forces me to admit— with a gross understatement, followed by an even grosser untruth. “You may be aware,” he said, “of the dissatisfaction of the men with the food being served to them.” Remembering the troubles of my friend at the stables, a simple “Yes, sir” seemed an adequate reply. To coin a phrase, the food was God-awful.

“Very well,” he went on, “I’m going to give you a great opportunity.” A clear lie, obviously. Captains did not give privates opportunities; they only gave them headaches. “You will be promoted to the rank of sergeant and put in charge of the mess.”

A nice calculation of the evils before me would have required an advanced type of computer. In the descending circles of hell, horse-burial details were clearly lower than mess sergeants—closer to the central fire and suffering. Mess sergeants suffered only social obloquy. But redemption worked the other way. The horses might get well or all die. But those who became mess sergeants all hope abandoned. Corporals, even little corporals, might become emperors, but no mess sergeant ever got to be a shavetail. However, the Captain had not offered me a choice; he had pronounced a judgment. “Yes, sir,” I said again, and was dismissed.

As things turned out, life proved tolerable. One help was that the food could not get worse; another, that one of the cooks was not without gifts which, when sober, he could be inspired to use. It only remained to convince the regimental sergeant major that after the cook’s Bacchic lapses the true function of the guardhouse was to sober him up, not to reform him. All in all, things began to look up. Although the very nature of the soldier requires that he beef about his food, the beefing in Battery D began to take on almost benevolent profanity. That is, until the Major entered our lives.

In real life—if I may put it that way—the Major was a professor, a renowned archeologist and explorer of lost civilizations, obvious qualifications for supervising regimental nutrition and hygiene. He turned his attention first to food. The rice we boiled, he correctly pointed out, seemed to flow together, in an unappetizing starchy mass. In the Andes, he said, they prevented this by boiling the rice in paper bags. Aside from the inherent implausibility of this procedure, it seemed to have no relation to the end sought. But the professor-turned-Major showed no inclination to debate the point; and an order is an order according to the Articles of War. After all, it seemed to make little difference, since the bags, and even the hemp that tied them, simply disappeared into the gelatinous mass. But our customers found otherwise. They reported an indissoluble residue, impervious to chewing, soon identified as wood pulp. The Major was the killing frost that nipped the tender buds of the battery’s good will toward me.

Then came the matter of the disposal of the dishwater in which the men washed their mess kits. Neither regulations nor regimental headquarters had considered, much less solved, this problem. However, we in the cookhouse had. We simply tipped the barrel over a small cliff behind the company street. No one criticized this eminently practical solution of a practical problem until the Major came along. He regarded it as unhygienic and again found the solution in Andean practice. There they had built fires within horseshoe-shaped, low stone walls and poured dishwater over the hot stones by the dipperful, turning it into a presumably sanitary steam. A ukase was issued to the kitchen police. Sullenly they built the stone horseshoe and, after diligent scrounging for wood, the fire. Appalachian stone proved to be more heat resistant than the Andean variety. An hour’s dipping hardly reduced the level of the dishwater and produced no steam. At this point the kitchen police, delivering a succinct statement of their view of the situation in general and of me specifically, poured the whole barrel of water over the fire, and signed off for the night. It was mutiny; but it was magnificent. Next morning, a new detail dumped the gruesome residue over the cliff. We resumed our former practice, leaving the stone horseshoe and a few charred logs as an outward and visible sign of the Major’s diligent attention to hygiene.

Realizing that the reader, like a court, must not be wearied with cumulative proof, I mention only the deplorable incident of the Colonel’s inspection and pass on. Lower officers did more than enough inspecting to maintain desirable standards. The Colonel’s perusal was rare and was of purely ritualistic significance. No one, least of all himself, looked for or would call attention to defects, not because they weren’t there, but because it would have been embarrassing. It would defeat the purpose of the ritual, just as it would for a visiting chief of state, reviewing a guard of honor, to point out a dusty shoe or a missing tunic button, or for the pope, being carried into St. Peter’s, to tell a cardinal that he had his hat on backward.

The Major, however, lacked a sense of occasion. He seemed unaware that in ritual, form, not substance, is of the essence, that the officers attending the Colonel were there as acolytes, not fingerprint experts. As the least of the acolytes, I joined the party at the mess hall and tagged along to the cookhouse. Everything shone. The cooks, sober and in clean aprons and hats, saluted. The Colonel returned their salute and murmured, “At ease,” as he turned to go. The Major chose this moment to hook his riding crop under a large and shining tub hanging against the wall and pull it out a few inches. He might have been Moses striking the rock. A stream of unwashed dishes and pans poured out and bounced about. The group froze as the Colonel looked hard at the Major and then asked our captain and first lieutenant to see him at his quarters after the inspection. He walked on.

The first necessity was profanity. Little could be added to the already exhaustive analysis of the Major’s failings. The shortcomings of the cooks and kitchen police hardly exceeded primitive stupidity. My own problems were not serious. Some sacrifice must be offered on the altar of discipline—passes curtailed, pay docked, and so on. But underlying opinion was clear. The real faux pas was the Major’s, and the Colonel would see it that way—as he did.

Meanwhile the summer was passing. The horses’ particular brand of pneumococcus seemed to lose its zest. As they recovered, they became more amenable to military discipline. Soon the drivers had the caissons rolling along; and the gunners grew proficient at mental arithmetic as they listened to the shouted numbers, twirled the wheels that moved their gun barrels, and learned to push home dummy shells, lock the breeches, and jump aside to avoid a theoretical recoil as lanyards were pulled.

South of the border the political temperature cooled as the days shortened. General Pershing came home empty-handed, rumors flew that the National Guard would be demobilized; but not before we had had a day of range practice, not before the effort and sweat of summer had been put to the test of firing live ammunition. Labor Day came and went. The mountain foliage began to turn, the blueberries to ripen on the hillsides. A few trenches were dug on a hill across a valley, enemy battery emplacements were simulated with plywood, notices were posted to warn berry pickers off the range on the chosen day. The Major was posted as range officer to ride over the target area before firing began to ensure that it was clear.

On a glorious autumn morning the regiment set out for the firing position, a plateau some miles beyond our camp at the far end of the military reservation. On the parade ground the sight of the full regiment in formation was a moving one; but when Battery D brought up the end of the column of march and our rolling kitchen took its place at the end of that, martial spirit suffocated under a pall of dust. Not a breath of air moved it. Only a wet handkerchief over the nose and mouth kept lungs from filling solid.

A brief respite came when the column halted and the kitchens moved up from the tail to the head of the batteries. The drivers watered and fed their horses while the gunners ate and then took their place. Even though the Major was far away on his assigned range patrol, we risked no chances with that meal—no boiled rice—there was too much live ammunition around. Not long after lunch the column debouched onto the plateau and moved straight across it. As Battery D emerged, the column broke into a trot, then swung at right angle into regimental front with guidons fluttering. When they were aligned, a bugle sent the whole command into a full gallop, a brave sight. As they reached firing position, they swung around, unlimbered guns and caissons, and took the horses, still excited and tossing their heads, to the rear.

We left the kitchen to the drivers and joined a group at the steps to a platform from which the Colonel was observing the terrain through field glasses. The last preparations for firing had been completed, gun crews and officers were in their places, range finders manned. Soon officers shouted numbers as they computed distances, angles, and elevations; wheels on the guns turned. The regulation procedure from here on was pretty conventional. One or two guns would fire a long and then a short—that is, on the first they would add to the estimated range, on the second, subtract. Having thus, hopefully, bracketed the target, they would split the difference, or make other correction, and everyone would be ready for business.

The Colonel turned to his second-in-command. “Range clear?” he asked with rising inflection. The words were repeated across the platform and down the steps. The words were picked up and rolled back as a receding breaker is by an incoming one. This time the inflection was reversed, assertive; not a question but an answer, “Range clear!” Then from the platform came the electrifying command: “Regimental salvo!”

The usual procedure might be conventional, but the Colonel was not. He would start this exercise with a bang that few present would forget. In sixteen guns shells were shoved home, breeches slammed shut; gunners jumped clear while lanyard sergeants watched for the signal. “Fire!” said the Colonel. The resultant roar was eminently satisfactory. Some of the horses snorted and gave a plunge or two. The whole hilltop across the valley burst into smoke and dust.

About a mile our side of it appeared a separate source of dust bursts, moving toward us at great speed, touching, so it seemed, only the higher mounds. An order to cease fire stopped the reloading, and field glasses centered on the speeding horseman. Word spread that it was the forgotten Major. As he came nearer, he seemed to be urging the horse to greater effort. Panic or rage or both had clearly taken over. He would certainly gallop up flushed and breathing hard, fling himself from the saddle, and run toward the steps shouting, “What damned fool …?” One could see him, stopped by the Colonel’s cold stare, salute and stammer out, “Range clear, sir!” I didn’t wait for the confrontation. The platform would soon be the scene of high words, possibly controversy, in any event, unpleasantness. It was clearly no place for a mess sergeant who belonged with his field kitchen.

For a few days much talk and questioning revolved about who said what to whom. Unfortunately I could not help with this since I had rejoined the kitchen group before the dialogue began and was quite as puzzled as the others about what had happened. Anyway, it was all forgotten in a few days when we broke camp for the move home and mustering out.

Years later I met the Major again. We had both exchanged military titles for somewhat higher civilian ones. But although we were to see a good deal of one another, not always under the pleasantest circumstances, it never seemed to me that our relationship would be improved by probing the events of that memorable range practice.