An honest telling of history, including deeply disturbing events such as the murder of Emmett Till, allows us to look at our past in a richer and more meaningful way.

-

Fall 2024

Volume69Issue4

Editor’s Note: Dr. Lonnie G. Bunch, III is the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and founding director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. The following essay was adapted from his introduction to the recent book Tragedy on Trial: The Story of the Infamous Emmett Murder Trial by Ron Collins.

One of the core principles at the heart of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture is to tell the “unvarnished truth,” a phrase often used by the late Dr. John Hope Franklin, the dean of African American historians. So much of a historian’s job is to uncover truths in the past, no matter how complicated or painful. We do it through intensive scholarship and meticulous research that leads to new evidence, new insights, and new interpretations.

Although the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi was one of the key moments in the civil rights movement, important details about his killers and the woman who accused him of impropriety have only emerged over the past several years. Historian and law professor Ron Collins makes extensive use of a copy of the long-lost transcript of the trial of Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam, the two white men charged with killing the boy and tossing his body into the Tallahatchie River.

It is a story that had been lost to time, and, as is often the case with historical examples of racial terror and injustice, it was also buried by people determined to obscure their own roles in maintaining a system that allowed it to happen.

Despite overwhelming evidence to support a conviction, his murderers were declared not guilty by an all-white jury in Sumner (self-advertised as "A Good Place to Raise a Boy") that deliberated for 67 minutes. The defense had originally tried a justifiable-homicide argument, based on Carolyn Bryant's claim that Emmett had assaulted her. Then, they switched to the claim that the body found in the river was not Emmett's, even though his mother had identified him, and his father's ring was on his finger. The jury went with the notion that the body could not be identified.

The killers' several accomplices were never charged.

Although the murder of Emmett in a barn at Shurden Plantation in Sunflower Country was one of the most pivotal events in American history, it was also sadly unremarkable, typifying the casual destruction of Black bodies in the Jim Crow South. In the crucible of racial terror in 1950s Mississippi (a state so tethered to its slaveholding past that it did not ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until 1995), the lynching of the boy known by his loved ones as Bo could have been nothing but just another Black boy killed. Another false accusation of sexual impropriety used as a pretext for racist violence. Another statistic.

Were it not for Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley (Bradley, at the time), those in power may have been able to act as so many others had before, protected by a racist system and shrouded in obscurity.

Mrs. Till-Mobley refused to allow the nation to look away, despite the incomparable pain of the death of her child, and this changed the country forever. When she chose to have an open-casket funeral at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, and allowed pictures to be taken of Emmett’s disturbingly disfigured face, it became a catalyst that reignited the civil rights movement.

To that point, much of the work done in the fight for equality had been in courtrooms, and included taking arguments all the way to the Supreme Court. But milestone victories like Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which formally (but not actually) banned segregated schools, although vital, were not enough to counteract the entrenched racism of the South. Indeed, they only served to spur violent backlash — including Emmett Till’s murder.

When Black World War II veterans returned home from Europe and Asia, they attempted to change things to reflect the freer and fairer lives they had experienced overseas, but those efforts were mostly carried out at the local level. Emmett’s murder was the first event to serve as a national wake-up call and to galvanize people. It demonstrated that folks had to confront the evils of segregation head-on and that all people of conscience must be active participants in improving the country.

A generation of civil rights activists pointed to the horrific murder as the clarion call to act, including Rosa Parks, who told Mrs. Till-Mobley that she was thinking of Emmett when she refused to relinquish her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus three months after Emmett's killing. Then, in 1960, there were the Greensboro Four, who sat down at a lunch counter to demand service at a segregated North Carolina Woolworth’s; in 1961, the Freedom Riders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, including a young John Lewis, began their very brave and dangerous campaign in the Deep South; and, in 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech on the eighth anniversary of Emmett’s death.

Emmett Till resonates with me personally on many levels: as a Black man, as a father, and as a historian. When I was contemplating the content of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I knew that Emmett’s story must be central to it, not just because it was a tragedy that had helped create a historic movement, but also because I had an important promise to keep.

During my tenure at the Chicago Historical Society, I had the great fortune to meet Mrs. Till-Mobley. She was gracious in spending time with me, allowing me to hear firsthand what she had gone through, and recounting her memories of her son. Just before her death in 2003, she spoke to me about how she had carried the burden of Emmett’s death and the meaning of his loss for nearly 50 years. She was tired. She wondered who would carry that burden of history and the weight of his memory when she was gone. I knew that this was a direct appeal to me and to the entire historical community to ensure that Emmett and countless other victims of racial terror would never be forgotten.

Her words echoed in my mind during the planning and creation of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The challenge before me was how to carry out Mrs. Till-Mobley’s wishes in a way that not only respected Emmett’s life, but also spoke to the broader importance of what he meant to the nation.

The potential for a profound tribute to the lives and legacies of Emmett and Mrs. Till-Mobley came in 2005, when the Department of Justice reopened the murder case and disinterred Emmett’s body, later reburying him in a new casket. The original was to be placed in storage, but, unfortunately, it was improperly stored in a shed and fell into disrepair.

When I found out about that, I reached out to Emmett’s cousin, Simeon Wright. The family asked me if we would like to take the casket into the museum’s collections to preserve it and help tell Emmett’s story. I was unsure whether it was appropriate to do so. The last thing I wanted to do was create a ghoulish spectacle that stripped Emmett of his humanity. Ultimately, in conversations with senior staff, we decided that the artifact was too important to leave out of the first national museum devoted to viewing America through an African American lens.

Emmett’s casket has proven to be one of the museum’s most powerful exhibits. Soon after our center opened, I witnessed its effect in action. A young Black woman was overcome with emotion as she stood next to the coffin, absorbing the magnitude of this simple container with a glass top that had revealed racism’s ugly truth for the world to see.

An older white man approached and asked if he could cry with her. She hesitated, and then agreed, and they locked arms and stood in silence, two strangers crying together over the ghastly murder of a child decades before. It was a moment of unguarded, shared humanity unlike any I had experienced. I think Mrs. Till-Mobley would have appreciated that her son was able to help visitors learn, heal, and grow together.

That is the power and promise of an honest telling of history. It allows us to look at our past in a richer and more meaningful way. It can bring people together to understand the human impact of crucial moments in time. And it enables us to gain a better perspective on our present by contextualizing where we have been and how we got where we are today. In so doing, we learn how to build a better future.

I have always felt that museums have an important role to play in addressing social and racial injustice by defining reality and giving hope. By seeking the unvarnished truth. But that duty does not belong only to cultural institutions or historians; it is the responsibility of anybody who is dedicated to the truth.

Black newspapers have always been an important voice in the chorus calling for equal rights. Pioneering editors like Robert Abbot of the Chicago Defender, William Monroe Trotter of the Boston Guardian, Charlotta Bass of the California Eagle, and Jefferson Lewis Edmonds of the Los Angeles Liberator realized that, as journalists, as guardians of a community seeking the equality that's central to the American promise, they had a sacred responsibility to act. The Black press continues to provide its readers with information often ignored by mainstream papers, thereby confronting the systems that help perpetuate racism.

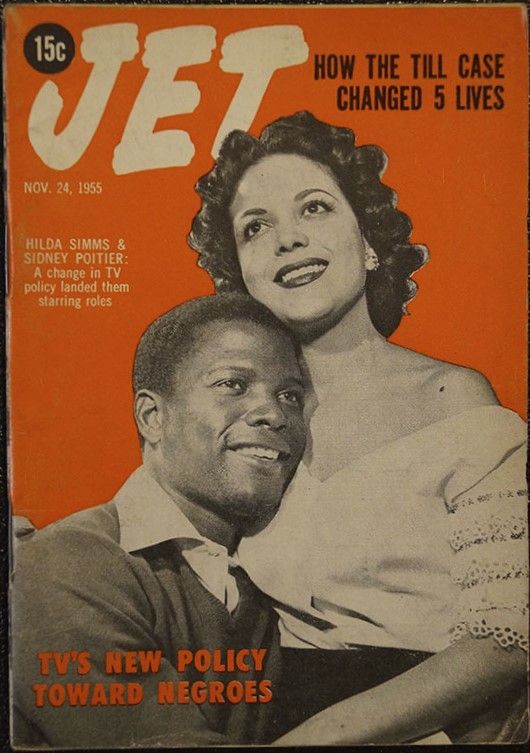

And this press was a vital witness to history during the trial of Emmett Till’s murderers. The most obvious contribution is the horrific photograph that David Jackson of Jet magazine took of Emmett in his casket, battered beyond recognition, a surrealistic approximation of a face that would haunt any person of conscience.

Although no mainstream newspaper would carry the gruesome picture, Jet’s editor John Johnson made the courageous decision to do so, and other African American publications followed suit.

The Black press also played a vital role in keeping an accurate record of the events of the trial, revealing other witnesses who may have been connected to Emmett’s kidnapping and murder, but who were not called to testify, and in debunking the myriad lies and half-truths in William Bradford Huie’s popular accounts of the event that have stubbornly persisted for decades.

With their contemporaneous reporting on the trial, the Black press also inspired historian Ron Collins to piece together in his recent book, Tragedy on Trial, the closing arguments that were inexplicably omitted from the trial transcript.

“Where do we turn to for the truth?” Professor Collins asks. Where, indeed? We live in an age of increasingly brazen efforts to rewrite history, to pretend that slavery was beneficial to the enslaved, to ban curricula that discuss race, and to remove certain books from libraries. It is nothing new, of course, this effort to maintain a founding myth sanitized and stripped of its ugliest parts.

Challenges to the entrenched power structure from the disenfranchised have always been met with a reactionary backlash; the greatest pushes to rewrite history books and to build statues to venerate the Confederacy came not directly after the Civil War, but in times when Black people were asserting their rights as human beings — during the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow era and then the civil rights movement.

Now, as a backlash to the grassroots movement and political campaigns in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis in 2020, we see the same kinds of reactionary efforts that aim to whitewash American history.

So, to answer Professor Collins’ question, the truth must come from historians and educators, legislators and corporate leaders, artists and writers, parents and students — in short, it must be a collective effort by all who recognize that an educated citizenry is vital to our democracy and that we cannot simply erase the distasteful parts of our history.

When reading about the concerted attempts to change the narrative of the trial, I think of the oft-quoted line from the Jimmy Stewart western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” We owe it to ourselves as a nation not to simply accept what we have been told about the past.

I would argue that we do a disservice to our children and grandchildren if we gloss over the reality of our history, in favor of a comforting fiction.

The Emmett Till story is an example of how history changes, depending on the narrators, how perception can become reality, and how, only through an honest appraisal of the evidence, can we piece together what truly happened.

One of my life’s great privileges was getting to know John Lewis, the civil rights icon and long-time Georgia Congressman who was instrumental in getting the National Museum of African American History and Culture built. I attended some of his bipartisan pilgrimages to milestones of the civil rights movement, including one to Mississippi, where we stood at the site of Emmett Till’s murder. It was a poignant moment, but Representative Lewis helped ease the pain by reminding us how Emmett had been a powerful rallying cry for justice. He was 15 when Emmett was killed; many years later, he explained that "Emmett Till was my George Floyd."

As we rode the buses back to Alabama, where the tour had originated, we stopped at a rest area, and Representative Lewis and his colleague from Maryland, Steny Hoyer and I went into the restroom. Sadly but unsurprisingly, racist comments were scrawled on the walls, a reminder that the hate in people’s hearts is not as easily changed as the laws.

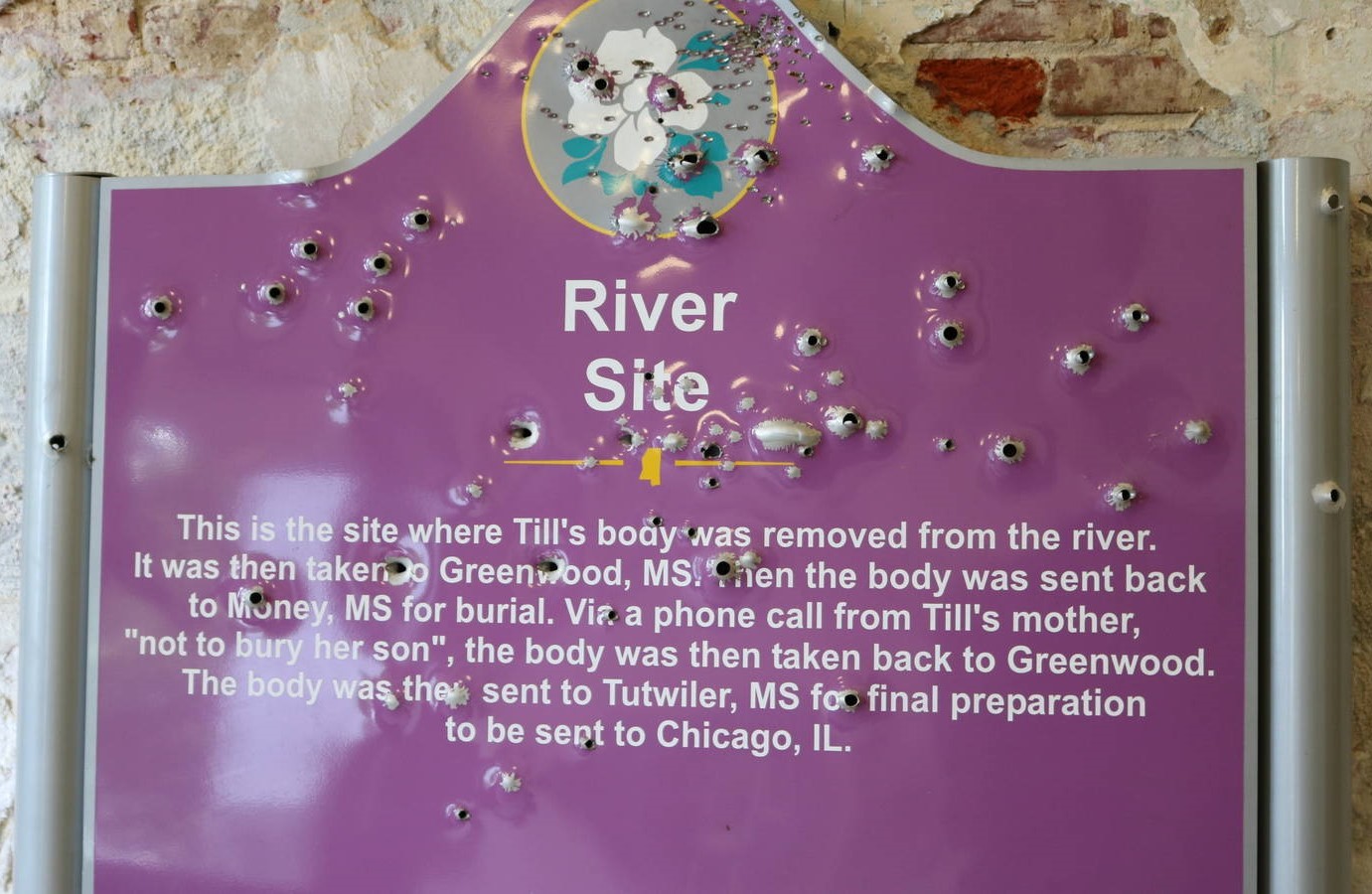

That reality was also evident in the bullet-riddled sign that marked the site where Emmett’s body was pulled out of the Tallahatchie River. In 2021, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History displayed one of several historical riverside markers that had been made and replaced by the Emmett Till Memorial Commission. Due to repeated acts of vandalism, the latest version had to be bulletproof steel. But, no matter how hard those with a vested interest in erasing Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley try, whether with bullets or censorship or laws, they will never be able to do so. The memory and legacy of Emmett and his mother belong to the world.

Recent events demonstrate the dichotomy inherent in the Emmett Till case. In one respect, the death in 2023 of 88-year-old Carolyn Bryant - who had accused Emmett making a sexual advance on her in her family's grocery store - closed out one of the most infamous chapters in American history, though it offered no satisfying resolution. Her claim had set the deadly chain of events in motion, and, despite the discovery in 2022 of a 1955 arrest warrant for her regarding the kidnapping of Emmett, she was never charged.

No one involved in the murder was legally punishment: Neither Mrs. Bryant, her husband, Roy and his half-brother, J. W. Milam - who kidnapped, pistol-whipped, cut off an ear, and shot the teenager in the head, then tied a 74-pound fan around his neck, using barb wire to secure it, and threw him into the river - nor the several other men involved in the crime, including three black employees of Bryant and Milam.

Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam confessed to the murder in a 1956 interview with William Bradford Huie in Look magazine. They were paid $4000 for their stories. Huie had originally concluded that four men had been involved in the murder, but his editor said that the magazine could only state that if the other two men signed a release, which Huie couldn't get. So, his story, which became the accepted version for decades, identified only the two acquitted killers, and it uncritically forwarded their claim that Emmett had bragged to them that he'd had sex with white women, that he showed no fear after being abducted, and had called his kidnappers bastards.

Carolyn Bryant allegedly told the author Timothy Tyson in 2007 that she had lied when she accused Emmett of groping her, that he didn't deserve to die, and that her then-husband was extremely violent. However, when Tyson was questioned about his evidence of that confession, he said that he hadn't recorded that part of his interview with her.

Emmett’s legacy is more secure than ever. In 2022, there were three milestones: the release of a wonderful film - simply called Till - about Emmett and Mamie. And there was the passage and signing of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, and President Biden named three historic sites as protected memorials: the Roberts Temple Church, where Emmett’s body had been displayed (now the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley and Roberts Temple National Monument); Graball Landing, where his corpse was discovered; and the Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse, the setting of the trial.

What were places of pain, of desperate attempts to thwart justice and rewrite history, will now forever stand as testaments to the resilience of a mother who demanded justice for her son and who helped the nation leap forward in its long search for redemption.

Meanwhile, the names Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam and Carolyn Bryant will be mere footnotes in history and will share in the ignominy and anonymity of other racists shunned by decent people who recognize the corrosive effects of hatred and who strive for a better nation.

Those who are dedicated to revealing the unvarnished truth and perfecting our union are true heroes.