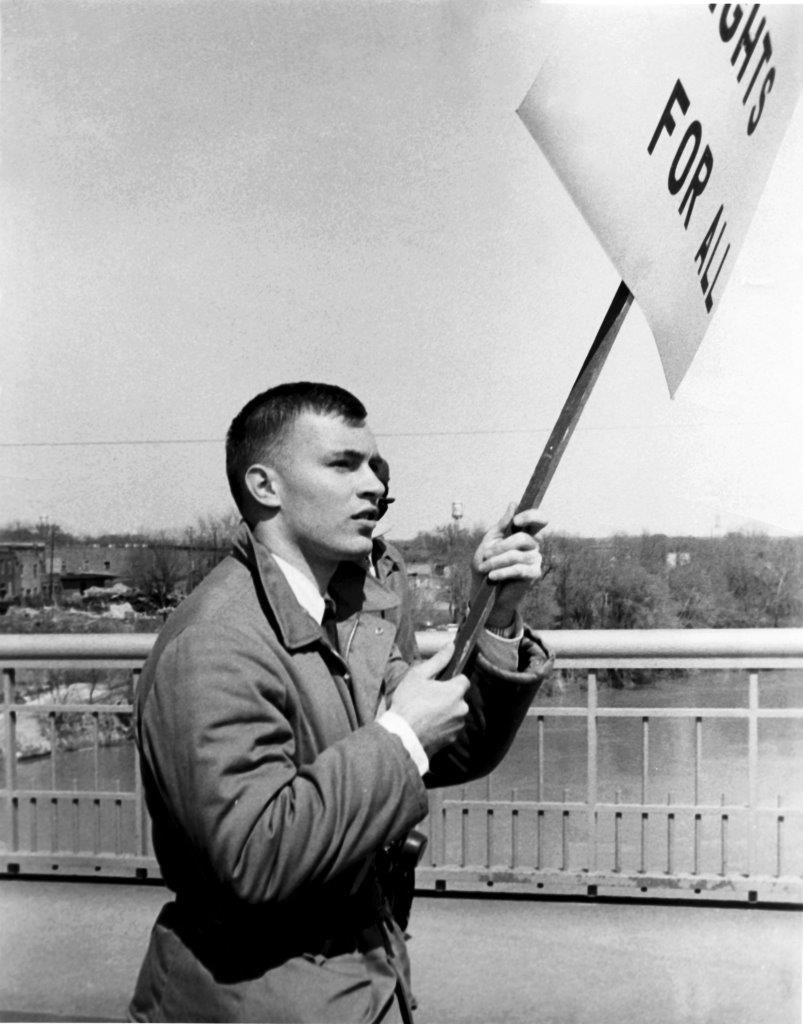

A college student in the march from Selma to Montgomery recalls the struggle for democracy in Alabama in 1965.

-

Spring 2023

Volume68Issue2

On the first weekend in March, 1965, TV images of brutal violence by the Alabama state police against civil rights demonstrators shocked the nation. Wielding batons and dogs, police killed one demonstrator and brutally beat many others as a few hundred otherwise-silent Black Americans marched peacefully across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on U.S. highway 80, heading from Selma to the Alabama capitol. Their offense? Demanding the right to vote guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Days after Bloody Sunday, Martin Luther King, Jr., along with leaders of other civil rights groups, issued a call for faith communities to join another march on the 21st.

I was then a senior at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, where I had just ended my term as editor-in-chief of the Griffin, the campus newspaper. Using my bully pulpit, I had endorsed Barry Goldwater for president just months before. In high school, I had been captured in the thrall of his pitch for liberty in Conscience of a Conservative. But, at the core, the right to vote was the first freedom in the lexicon of liberty. There can be no liberty for people who have no place at the table, whose voices are not heard, and whose personal sovereignty is not respected. The terror visited upon the marchers at the bridge was proof to me that the right to vote must be assured to restore civility to the land. When I heard of Martin’s call, my response was “Yes, we will join hands.”

This was the first time I could recall Black civil rights leaders reaching out to white America with an open call for support. Until then, I understood that civil rights leaders wanted the protests, the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and the marches to be an expression of Black power, led by Black organizations, and representing the voice of the Black community. It was their opportunity to be recognized and heard. I felt that whites, no matter how sympathetic to the goals of the movement, were not welcome as open participants due to the fear that white activists would co-opt and dominate the movement.

But Martin’s call sent a new message. White brothers and sisters were openly invited to stand together, to march arm-in-arm, to show solidarity, white with Black America.

The necessity of the call was clear. President Lyndon Johnson had introduced the Voting Rights Act in a joint session of Congress a week after the carnage on the bridge. But the success of Johnson’s voting rights bill was uncertain at best. Its passage demanded that white America join the plea for legislation to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment. Black America lacked the political power to overwhelm the power of southern racists like James O. Eastland, the Mississippi senator who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee. A voting rights act would never pass the Senate without broad support from white America.

Heeding Dr. King’s call, I suggested to my fellow student leaders that we organize a Canisius contingent for the second march. Support from them coalesced overnight. College officials agreed to allow the student council to allocate student fees to pay for the bus, provided at least one Jesuit faculty joined the trip. It all seemed to be coming together. I expected the obstacles would be confronted in Selma, but the biggest obstacles soon emerged from my own white culture.

I met with the Army captain who served as the ROTC faculty advisor for the cadets' Tactical Unit, which I led as the cadet captain. My objective was to discuss which of the cadet lieutenants would command the Tactical Unit during Buffalo’s St. Patrick’s Day parade on the same weekend as the march in Selma. When I told him I would be leading the Canisius delegation to march for voting rights in Selma, he immediately interrupted to declare: “You can’t go. You must lead the unit in the parade.”

See also: The Week the World Watched Selma, by Stephen B. Oates

I expressed confidence that my presence was not essential to the parade. Any of the platoon leaders could lead the T.U. in my absence. But the captain ordered me to command the unit. I objected, arguing that both the march in Selma and the St. Patty’s parade were college-sanctioned activities and that he could not stop me from participating in Selma.

He bristled, the veins popping in his neck. His words spitting through gritted teeth, he threatened to have me cashiered from the corps of cadets and drafted as a private if I failed to perform my duty as commander on St. Patrick’s Day. He was clearly doing his damnedest to intimidate me to stop me from going to Selma.

My hackles raised, I accused him of being a racist who was trying to interfere with my First Amendment rights as an American citizen. “I am not yet in the Army; I’m still a civilian. If the Army is in the business of depriving people of their rights, then I do not want to be commissioned.” I spun on my heels and stormed out of his office in a rage, without saluting.

The price of fighting for the rights of Black Americans in Alabama had suddenly escalated. This was no longer just about the discomforts of 20 hours on a bus, or confronting the threat of racist violence in a distant place. This was now about my life, my future, my freedom to help create a better future. I could not allow myself to be intimidated. The racism that we saw a thousand miles away on TV was right here in Buffalo. I had to fight back to protect my freedom from being trapped in the quagmire of racism and discrimination that trapped so many more than Black Americans.

I asked to see Father Edward Gillen, the Jesuit vice president of student affairs. After I told him about my exchange with the captain, Gillen remained uncommonly silent and still, for a minute. He was authoritarian, accustomed to being in charge, but I had no idea what to expect. Then he picked up the phone and called the ROTC commanding officer. He first recounted my version of the conversation and asked if I had indeed been threatened with dismissal from the corps. He listened intently for some minutes, then announced in a guttural, commanding voice: “If Yuhnke is not allowed to go to Selma, the days of ROTC on this campus are numbered.”

The next day, I was summoned to the office of the acting ROTC commander. His expression was dour as he reluctantly looked me in the eye and said “You are not required to command the T.U. Dismissed.” Gillen’s defense of my leadership in planning the Selma trip felt like a victory over racism. Freedom had won a battle. But that was hardly the end of the war.

That weekend at the dinner table with mom and dad, I announced that I was organizing Canisius students to participate in the voting rights march in Selma the following weekend. I was leading a delegation of students to join the march in Selma. Mom worried that we would get hurt. One white pastor had already been murdered in Selma; other murders of protestors in Selma were yet to come. Fearing that I would be a victim of hate violence, she urged me not to go. While she spoke, dad sat silent, growing red-faced.

I could tell his anger was rising, but I had no reason to suspect it would be directed at me. When mom fell silent, he exploded: “No son of mine would do a thing like that! If you go, I don’t ever want to see you in this house again!”

The vehemence of his reaction stunned me. It took me minutes to take in the import of this unexpected revelation of my dad’s attitude. He had never expressed, at least with me, this kind of hostility to Blacks or civil rights. The issue that was rending the nation had never been discussed in our family. Now it was rending my family and confronting me with an impossible choice.

The situation did not lend itself to reasoning. I responded from my heart: “Dad, I feel that what is happening in the South affects us all, and I feel called to bear witness. History is being made, and I want to be part of it.”

He slammed his fist: “Well, that’s it! Get out."

We expected the 20-hour ride from Buffalo to Selma to be a challenge in boredom. After loading bed rolls and packs, and settling into less-than-commodious seats, the first 12 hours to Nashville lived up to our expectations. We arrived in the dead of night, stopping long enough to stretch our legs, make a pit stop, and change drivers. The new driver, a southern boy with a drawl thick enough to split with an ax, proved to be surly and mean as soon as he learned our mission. After pulling out onto the highway, he turned up the heat as far as it would go. It took a while for us to realize that the bus was being converted into a convection oven. So we opened all the windows, letting in the cold March night air. The bus quickly cooled, and we all began to don the layers we had stripped off. But the driver then put on the AC, quickly dropping the interior temperature to match the air outside. Now, we were forced to close the windows and add all our layers, including the winter coats we had started with in Buffalo.

When we arrived in Selma, our driver refused to drive us to our destination, the Negro Baptist Church in the city’s Black neighborhoods. Instead, he dropped us off on a back street near downtown, without giving us any clear directions. Whether this was an act of spite or fear was not clear.

We had been told that, at the church, we could stash our bedrolls for the day, and sleep that night when we returned from the first day of the march. The federal district court had ordered Governor Wallace and the state police to allow all the marchers to proceed on a portion of the right-of-way of US 80, but the order also limited to a few hundred the number of marchers allowed to continue to Montgomery after the first day. We had booked the bus to return to Buffalo on Sunday morning.

Eventually, someone gave us directions to the church. The route required that we walk a few blocks through white neighborhoods before reaching the Black part of town. The dividing line was not hard to spot. On one side of a cross street, the roads were paved and flanked by sidewalks and trees. Beyond the boundary street, we found ourselves walking on well-worn footpaths in the dirt along a gravel street. The energy also shifted markedly when we crossed from white to Black. Where we had been dropped off, the early-morning streets were largely empty of cars or pedestrians. But across the borderline, there was a bustle in the air.

A group of five or six young boys caught sight of us carrying our packs and duffels. They ran to greet us, striking up quite a chatter as they asked where we had come from and how we had got there. They proudly escorted us when they learned we were headed for First Baptist Church.

Inside the sanctuary, we stowed our bedrolls on and under pews. We were directed to gather down the street in front of Brown’s Chapel. The crowd milled around with the nervous energy of anticipation tinged with an edge of unacknowledged fear. Lurking in everyone’s mind were the images from Bloody Sunday, two weeks earlier, when state troopers with clubs and dogs attacked unarmed, peaceful demonstrators who had taken strict vows to follow Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Gandhian commitment to non-violence.

We knew that a federal judge had ordered Governor Wallace to allow the march to proceed along US 80, but no one was confident that the agents of state power would honor the First Amendment rights embodied in that order, any more than they honored the right to vote guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment. It would be easy enough to honor the judge’s order in the breach by finding excuses to disrupt the march by deploying the tools of state terrorism perfected during decades of KKK burnings, public lynchings, and other strategies of repression.

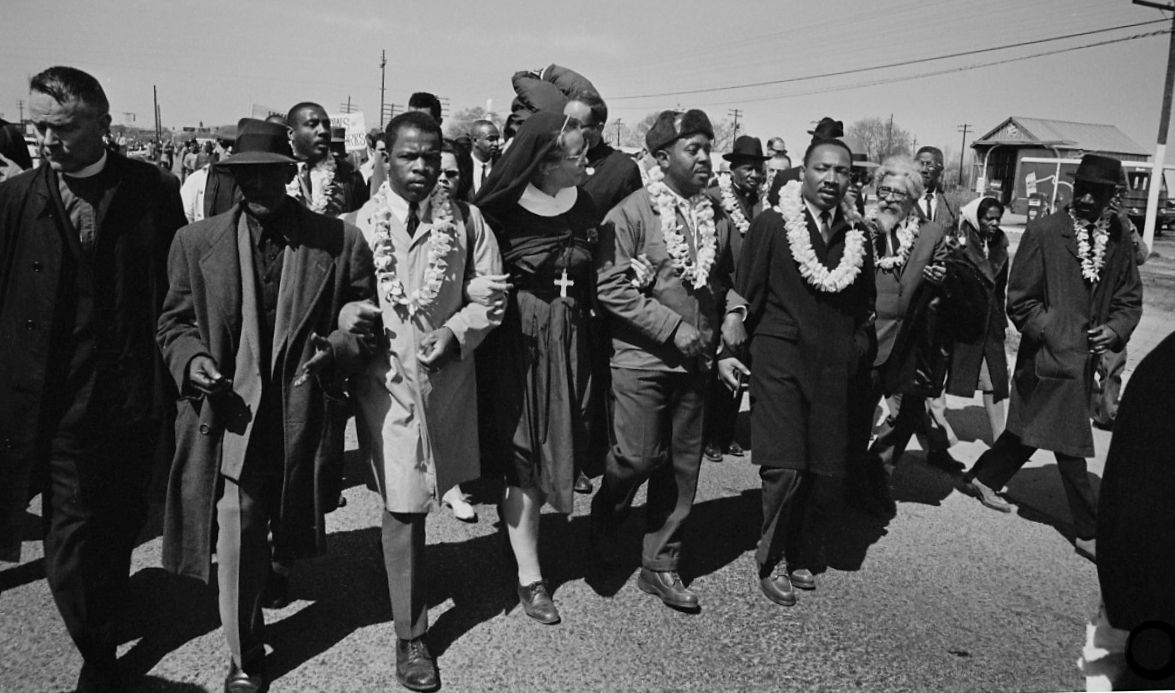

Ralph Abernathy emerged first onto the elevated portico of Brown’s Chapel overlooking the crowd of marchers. He was immediately recognizable as the leader of the Bloody Sunday march who had defied the state police command to disperse. He was accompanied by others who we learned to recognize later as C.T. Vivian and John Lewis. We waited anxiously for Dr. King to appear, certain that the march would not begin without him. Soon, he joined the group on the portico and stepped to the makeshift podium.

The crowd had now swelled to fill the street. Its size could not be estimated from the vantage of someone within the assemblage. I could not see the edges of the crowd from where I stood across the street from the chapel. Our challenge was to keep all the Canisius contingent in sight. We asked our fellow students to stay near the college banner that we carried, until we received instructions about how to form up for the march.

Dr. King welcomed the multitude. The sound system was not great. We struggled to make out his words as his voice reverberated from the buildings lining the street. But his words filled our hearts like a call to worship at the shrine of equality and freedom. He reminded everyone of the historical importance of the struggle to achieve the promise of the 15th Amendment, which had been ratified to ensure that the sacrifice America had endured during the Civil War was not in vain. And yet, for nearly 100 years, the right to vote guaranteed to former slaves had been rendered a dead letter by Jim Crow. It had to be resurrected.

King told us that President Johnson had federalized the Alabama National Guard. Cheers erupted from the crowd because we all understood that removing command of the Guard from the hands of Governor Wallace ensured that President Johnson was effectively disarming the state to stop Wallace from deploying state terrorism to disrupt the march. A repeat of Bloody Sunday was now unlikely. Tension in the crowd transformed into enthusiasm as everyone seemed to feel more confident that the day would be peaceful.

Our Canisius group began to walk, with two students at the front carrying the blue and gold college banner. We soon began to march through the few blocks of the Black neighborhood that separated us from downtown, where the route would follow US 80 across the now-infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge. When we turned the corner onto highway 80, we were greeted by counter-protestors standing two and three ranks deep shouting angry epithets and carrying signs demanding “Nigger-lovers go home.”

As we approached the bridge, the name emblazoned on it above the pavement evoked images of the brutal beatings of marchers broadcast on TV two weeks before. The memory sent a momentary flush of fear through my veins, but it quickly dissipated with the realization that no Alabama state troopers were in sight. Only the National Guard troops, now under federal command, lined the route of the march. No phalanxes of armed forces blocked our route. No bull horns shouted commands to “turn around.”

We were safe, so long as we remained within the two lines of Guard troops that separated us from the angry shouts from the counter-protestors. The mean, silent expressions on the faces of many Guardsmen revealed their sympathy with our antagonists, but they were under orders to prevent conflict.

Once we got across the Alabama River, the route quickly transformed from urban landscape to open fields marked by occasional farmsteads rising to break the perfectly flat horizon. This was the “black belt” of Alabama, which described both the rich black loam where cotton thrived and 87 percent of the population. The correlation between soil and inhabitants was not coincidental. Cotton production on this land before the invention of mechanical pickers was economically viable only because of the labor provided by the slave labor system, as well as the postbellum system of sharecropping.

Despite the majority-Black population of the region, in most counties, not a single African American resident was registered to vote. Even Black professionals —teachers, medical practitioners, and attorneys — with advanced degrees and resources to pay the poll tax were not allowed to register because they supposedly did not pass the literacy test.

Only whites were allowed to vote in the Democratic Party primaries, which elected all officials, including sheriffs, judges, county commissioners, and registrars who exercised state power. No public official owed his job, or his allegiance, to a single Black voter. It was clear why the streets in Black neighborhoods were not paved, why there were no sidewalks, and why sheriffs felt free to inflict extreme, even deadly force on peaceful, unarmed Black residents. Democracy does not serve those who cannot vote.

We peeled off layers of clothes as the day warmed under a bright sun. A New York Times reporter interviewed me during a water break. My comment thanking the president for nationalizing the Guard to protect the marchers was quoted the next day, but without attribution. The route covered about nine miles before we reached the turn-around point. Except for the few hundred marchers who were allowed by court order to continue to Montgomery, most of us boarded buses and cars for the return to Selma.

After walking for hours, waiting for a ride, and driving back to Selma, we arrived after dark. As we turned off US 80 towards Brown’s Chapel and the Baptist Church, where our sleeping bags waited, I realized that the streets were completely dark, except for interior lamps that shone through an occasional uncurtained window. There were no street lights.

There were also no Guardsmen or any other badged authorities who could be relied upon for our protection. The authority of President Johnson had no presence here. As we climbed off the busses into the dark, it struck me how vulnerable the Black residents were to being brutalized by hooded, faceless marauders acting out the same anger that threatened us earlier that morning.

Once again, we found ourselves surrounded by young Blacks, all boys, who followed or escorted us into the Baptist Church. From them, we learned that a cordon of Black men patrolled the perimeter streets of the neighborhood to provide early warning if police, sheriff deputies, or white vigilante groups ventured across the line. No one said whether the perimeter patrol carried weapons, but I doubted that they did, since we did not see any weapons being carried or displayed by our Black hosts. If marauders entered, the only apparent recourse was to shout out a warning.

Inside the church, I struck up a conversation with an intense, wide-eyed young man who was full of curiosity about us. “Where did you come from? How long did it take?” he said. The only question he did not ask was “Why did you come?” For him, that question did not a demand an explanation. He said he was 11 years old.

He shared with us his story of being chased from the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday. Two state troopers had targeted him. He ran. They chased him back through the Black neighborhood to the Baptist Church, where he expected to find refuge. But the troopers chased him into the church, cornering him behind the altar at the base of the 16-foot-high stained-glass window depicting a welcoming Christ with outstretched arms.

He recounted the story as we stood at the front pew. I glanced up at the stained glass. A gaping four-to-five-feet-high hole had been smashed through the leaded glass panes near the lower right edge. “How was the window broken?” I asked. The boy explained that he had been forced to jump through the glass to escape a relentless pummeling by the troopers. He had a still- healing gash on his forehead to confirm the story.

He smiled with pride, wearing his wound as a badge of honor. His courage in pursuing the respect that was his due as a member of the human race, and his constitutional rights as an American, filled me with awe and inspiration.

We bedded down on and under the pews with all interior lights blazing. Still, after enduring the bus ride through Hell the night before, and a day of walking nine miles in the sun, I fell asleep in an instant.

Early the next morning, we packed our gear to board the bus home. This time, a different driver willingly met us outside the church. As we stashed our gear into the cargo bays, a cadre of younger Black boys gathered around to watch. No chattering this time. They had wide-eyed expressions suggesting awe and longing, but they remained silent. Having slept fitfully on the hard wooden surfaces, we, too, had little energy for even polite chatter.

Then, as I turned to climb onto the bus, a boy of six or seven with a wide, toothy grin thrust a giant Hershey bar into my hand. My instinct was to say, “No, I can’t take this from you.”

I felt I should be giving him a gift for the kindness and hospitality he had shown these visiting strangers from afar. Then I realized he was offering a gesture of friendship that could not be refused. But I could not think of a thing to give in return. I wrapped his small hand in mine, bent down with a grateful smile, and said, “Thank you.” Others were waiting behind me to board.

With moistened, blurry eyes, I turned and stumbled up the stairs to find a seat.

When we arrived back on campus, hundreds of students gathered to greet us in the assembly hall. I confirmed that I witnessed how state power was being used to suppress the freedom of Black Americans. I understood that federal power had to be used to protect the rights enshrined in the Constitution. I believed in democracy. I believed that being a patriot meant defending the Constitution for all Americans. And the Constitution included the Fifteenth Amendment. “Denying the right to vote to any American is a violation of the Constitution," I said to those who greeted us back on campus. "The rights we marched to defend are the rights of all Americans. This is not a Negro problem; this is an American problem that demands action by Congress.”

At home, in uniform, and in Selma, I had seen and felt the hostility and hate that Black Americans experienced every day. I felt ashamed that the systemic discrimination that undermined the opportunities and the lives of my fellow citizens was part of the America I loved. I was free to leave behind the hostility and hate that infected Selma and most of the South, but the young Black boys we met in Selma did not share that privilege. The world had to change.