The more fiercely the Confederacy fought for its independence, the more bitterly divided it became. To fully understand the vast changes which the war unleashed on the country, you must first understand the plight of the Southerners who didn’t want secession.

-

March 1989

Volume40Issue2 -

Summer 2025

Volume70Issue3

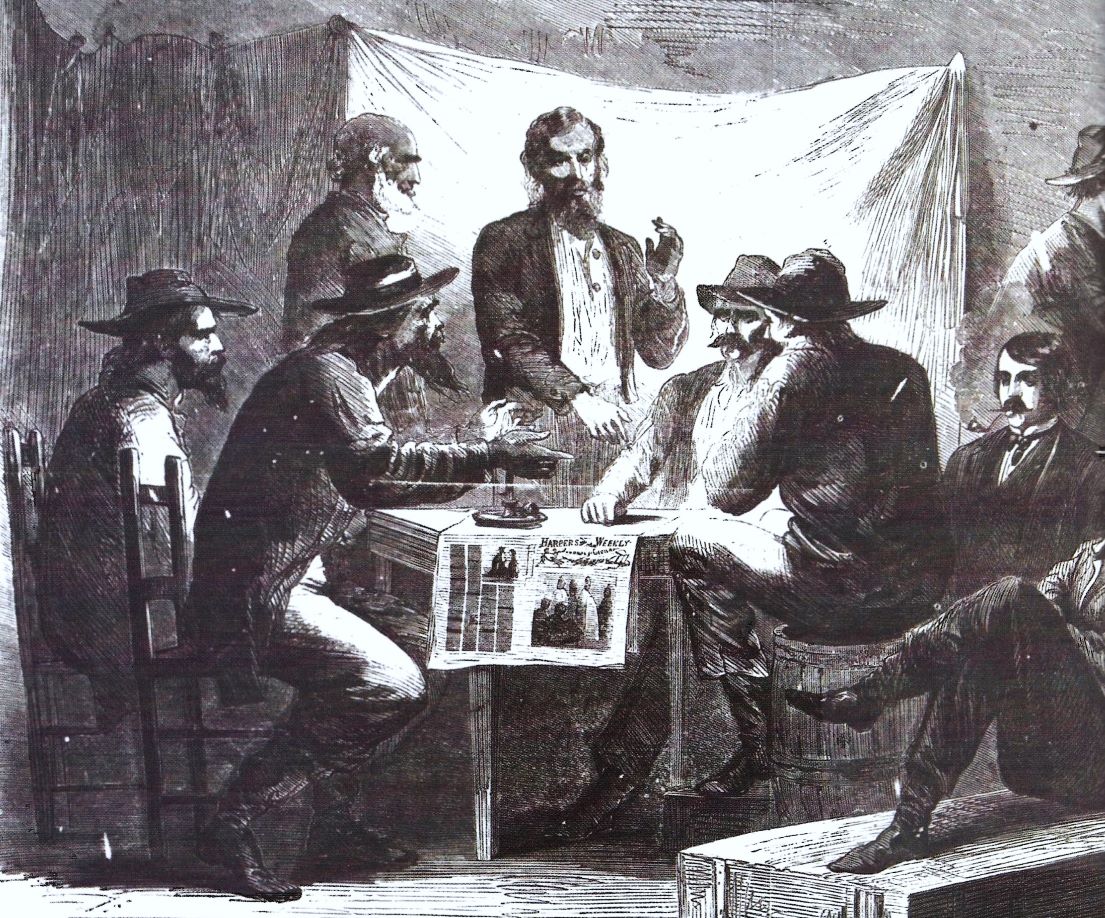

Americans tend to think of the Civil War as a titanic struggle between two regions of the country, one united in commitment to the Union, the other equally devoted to its own nationhood. Yet neither North nor South was truly unified. Lincoln was constantly beset by draft resistance, peace sentiment, and resentment of the immense economic changes unleashed by the war. Internal dissent was, if anything, even more widespread in the wartime South. Not only did the four million slaves identify with the Union cause, but large numbers of white Southerners came to believe that they had more to lose from a continuation of the war than from a Northern victory. Indeed, scholars today consider the erosion of the will to fight as important a cause of Confederate defeat as the South’s inferiority in manpower and industrial resources. Even as it waged a desperate struggle for independence, the Confederacy was increasingly divided against itself.

This was a matter of conflict more than simple war weariness. The South’s inner civil war reflected how wartime events and Confederate policies eventually reacted upon the region’s distinctive social and political structure. Like a massive earthquake, the Civil War and the destruction of slavery permanently altered the landscape of Southern life, exposing and widening fault lines that had lain barely visible just beneath the surface. The most profound revolution, of course, was the destruction of slavery. But white society after the war was transformed no less fully than black.

From the earliest days of settlement, there had never been a single white South. In 1860 a majority of white Southerners lived not in the plantation belt but in the upcountry, an area of small farmers and herdsmen who owned few slaves or none at all. Self-sufficiency remained the primary goal of these farm families, a large majority of whom owned their land. Henry Warren, a Northerner who settled in Leake County in Mississippi’s hill country after the war, recalled white families attending church “dressed in homespun cloth, the product of the spinning wheel and hand loom, with which so many of the log cabins of that section were at that time equipped.” This economic order, far removed from the lavish world of the great planters, gave rise to a distinctive subculture that celebrated mutuality, egalitarianism (for whites), and proud independence. But so long as slavery and planter rule did not interfere with the yeomanry’s self-sufficient agriculture and local independence, the latent class conflict among whites failed to find coherent expression.

It was in the secession crisis and subsequent Civil War that upcountry yeomen discovered themselves as a political class. The elections for delegates to secession conventions in the winter of 1860-61 produced massive repudiations of disunion in yeoman areas. Once the war had begun, most of the South’s white population rallied to the Confederate cause. But from the outset disloyalty was rife in the Southern mountains. Virginia’s western counties seceded from the Old Dominion in 1861 and two years later reentered the Union as a separate state.

In East Tennessee, long conscious of its remoteness from the rest of the state, supporters of the Confederacy formed a small minority. This mountainous area contained a quarter of the state’s population but had long been overshadowed economically and politically by the wealthier, slave-owning counties to the west. A majority of Tennessee’s whites opposed secession, although once war had begun a popular referendum supported joining the Confederacy. But East Tennessee still voted, by a two-to-one margin, to remain within the Union. Indeed, a convention of mountain Unionists declared the state’s secession null and void and “not binding” on “loyal citizens.” The delegates called for the region’s secession from the state (an idea dating back to the proposed state of Franklin in the 1780s). Andrew Johnson, who had grown to manhood there, was the only United States senator from a seceding state to remain at his post in Washington once the war had begun, and in August 1861 East Tennessee voters elected three Unionists to represent them in the federal Congress.

Meanwhile, almost every county in the region saw Unionist military companies established to disrupt the Confederate war effort. In July 1861 the local political leader William B. Carter traveled to Washington, where he proposed to President Lincoln that Unionists try to cut East Tennessee off from the rest of the Confederacy by burning railroad bridges. Carter later claimed that Gen. George B. McClellan promised that once this had been done, a Federal army would liberate the area.

Carter’s plan proved to be a disaster for East Tennessee Unionists. Four bridges were in fact burned, but others proved too heavily guarded. In one case Unionists overpowered the Confederate guards only to discover that they had misplaced their matches. And it was a Confederate army, not a Union one, that invaded East Tennessee in force after these incidents. Several men were seized and summarily executed, and hundreds of Unionists were thrown in jail. The result was a massive flight of male citizens from the region. Many who made their way through the mountains to safety subsequently returned as members of the Union army. Felix A. Reeve, for example, one of the earliest exiles, reentered East Tennessee in 1863 at the head of the 8th Regiment of Tennessee Infantry. All told, some thirty-one thousand white Tennesseans eventually joined the Union army. Tennessee was one of the few Southern states from which more whites than blacks enlisted to fight for the Union.

Throughout the war East Tennessee remained the most conspicuous example of discontent within the Confederacy. But other mountain counties also rejected secession from the outset. One citizen of Winston County in the northern Alabama hill country believed yeomen had no business fighting for a planter-dominated Confederacy: “all tha want is to git you … to fight for their infurnal negroes and after you do their fightin’ you may kiss their hine parts for o tha care.” On July 4, 1861, a convention of three thousand residents voted to take Winston out of the Confederacy; if a state could withdraw from the Union, they declared, a county had the same right to secede from a state. Unionists here carried local elections and formed volunteer military bands that resisted Confederate enlistment officers and sought to protect local families from harassment by secessionists.

Georgia’s mountainous Rabun County was “almost a unit against secession.” As one local resident recalled in 1865, “You cannot find a people who were more averse to secession than were the people of our county. … I canvassed the county in 1860–61 myself and I know that there were not exceeding twenty men in this county who were in favor of secession.” Secret Union organizations also flourished in the Ozark Mountains of northern Arkansas. More than one hundred members of the Peace and Constitutional Society were arrested late in 1861 and given the choice of jail or enlisting in the Confederate army. As in East Tennessee, many residents fled, and more than eight thousand men eventually served in Union regiments.

Discontent developed more slowly outside the mountains. It was not simply devotion to the Union but the impact of the war and the consequences of Confederate policies that awakened peace sentiment and social conflict. In any society war demands sacrifice, and public support often rests on the conviction that sacrifice is equitably shared. But the Confederate government increasingly molded its policies in the interest of the planters.

Within the South the most crucial development of the early years of the war was the disintegration of slavery. War, it has been said, is the midwife of revolution, and whatever politicians and military commanders might decree, slaves saw the conflict as heralding the end of bondage. Three years into the conflict Gen. William T. Sherman encountered a black Georgian who summed up the slaves’ understanding of the war from its outset: “He said … he had been looking for the ‘angel of the Lord’ ever since he was knee-high, and, though we professed to be fighting for the Union, he supposed that slavery was the cause, and that our success was to be his freedom.” On the basis of this conviction, the slaves took actions that not only propelled the reluctant North down the road to emancipation but severely exacerbated the latent class conflict within the white South.

As the Union army occupied territory on the periphery of the Confederacy, first in Virginia, then in Tennessee, Louisiana, and elsewhere, slaves by the thousands headed for the Union lines. Long before the Emancipation Proclamation slaves grasped that the presence of occupying troops destroyed the coercive power of both the individual master and the slaveholding community. On Magnolia Plantation in Louisiana, for example, the arrival of the Union army in 1862 sparked a work stoppage and worse. “We have a terrible state of affairs here,” reported one planter. “Negroes refusing to work. … The negroes have erected a gallows in the quarters and [say] they must drive their master … off the plantation hang their master etc. and that then they will be free.”

Even in the heart of the Confederacy, far from Federal troops, the conflict undermined the South’s “peculiar institution.” Their “grapevine telegraph” kept many slaves remarkably well informed about the war’s progress. And the drain of white men into military service left plantations under the control of planters’ wives and elderly and infirm men, whose authority slaves increasingly felt able to challenge. Reports of “demoralized” and “insubordinate” behavior multiplied throughout the South. Slavery, Confederate Vice-President Alexander H. Stephens proudly affirmed, was the cornerstone of the Confederacy. Accordingly, slavery’s disintegration compelled the Confederate government to take steps to save the institution, and these policies, in turn, sundered white society.

The impression that planters were not bearing their fair share of the war’s burdens spread quickly in the upcountry. Committed to Southern independence, most planters were also devoted to the survival of plantation slavery, and when these goals clashed, the latter often took precedence. After a burst of Confederate patriotism in 1861, increasing numbers of planters resisted calls for a shift from cotton to food production, even as the course of the war and the drain of manpower undermined the subsistence economy of the upcountry, threatening soldiers’ families with destitution. When Union forces occupied New Orleans in 1862 and extended their control of the Mississippi Valley in 1863, large numbers of planters, merchants, and factors salvaged their fortunes by engaging in cotton traffic with the Yankee occupiers. Few demonstrated such unalloyed self-interest as James L. Alcorn, Mississippi’s future Republican governor, who, after a brief stint in the Southern army, retired to his plantation, smuggled contraband cotton into Northern hands, and invested the profits in land and Union currency. But it was widely resented that, as a Richmond newspaper put it, many “rampant cotton and sugar planters, who were so early and furiously in the field of secession,” quickly took oaths of allegiance during the war and resumed raising cotton “in partnership with their Yankee protectors.” Other planters resisted the impressment of their slaves to build military fortifications and, to the end, opposed calls for the enlistment of blacks in the Confederate army, afraid, an Alabama newspaper later explained, “to risk the loss of their property.”

Even more devastating for upcountry morale, however, were policies of the Confederate government. The upcountry became convinced that it bore an unfair share of taxation; it particularly resented the tax in kind and the policy of impressment that authorized military officers to appropriate farm goods to feed the army. Planters, to be sure, now paid a higher proportion of their own income in taxes than before the war, but they suffered far less severely from such seizures, which undermined the yeomanry’s subsistence agriculture. By the middle of the war, Lee’s army was relying almost entirely upon food impressed from farms and plantations in Georgia and South Carolina.

The North Georgia hill counties suffered the most severely. “These impressments,” Georgia’s governor Joseph E. Brown lamented in 1863, “have been ruinous to the people of the northeastern part of the State, where … probably not half a supply of provisions [is] made for the support of the women and children. One man in fifty may have a surplus, and forty out of the fifty may not have half enough. … Every pound of meat and every bushel of grain, carried out of that part of the State by impressing officers, must be replaced by the State at public expense or the wives and children of soldiers in the army must starve for food.” The impressment of horses and oxen for the army proved equally disastrous, for it made it almost impossible for some farm families to plow their fields or transport their produce to market. These problems were exacerbated by the South’s rampant inflation.

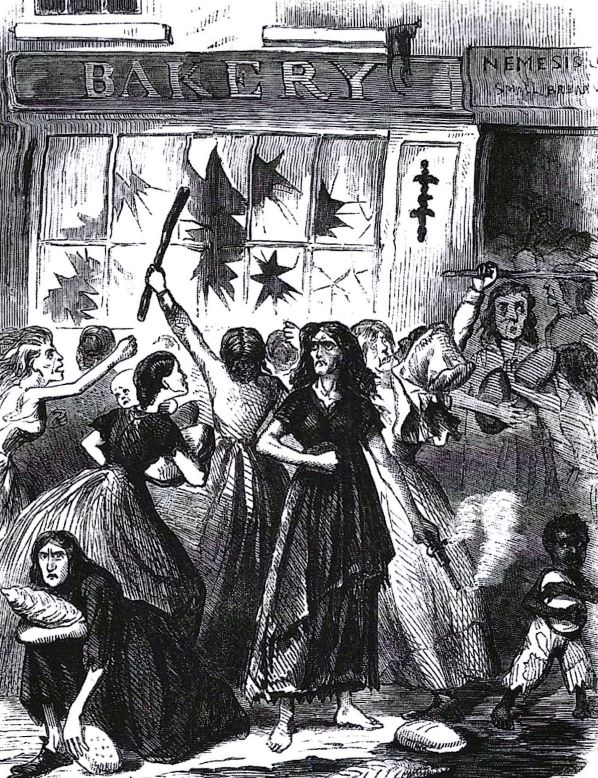

During the war poverty descended upon thousands of upcountry families, especially those with men in the army. Food riots broke out in Virginia and North Carolina. In 1864 a group of farmers in Randolph County, Alabama, sent a poignant petition to Confederate President Jefferson Davis describing conditions in their “poor and mountainous” county: “There are now on the rolls of the Probate court, 1600 indigent families to be Supported; they average 5 to each family; making a grand total of 8000 persons. Deaths from Starvation have absolutely occurred. … Women riots have taken place in Several parts of the County in which Govt wheat and corn has been seized to prevent Starvation of themselves and families. Where it will end unless relief is afforded we cannot tell.”

But above all, it was the organization of conscription that convinced many yeomen the struggle for Southern independence had become “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Beginning in 1862, the Confederacy enacted the first conscription laws in American history, including provisions that a draftee could avoid service by producing a substitute and that one ablebodied white male would be exempted for every twenty slaves. This legislation was deeply resented in the upcountry, for the cost of a substitute quickly rose far beyond the means of most white families, while the “twenty Negro” provision—a direct response to the decline of discipline on the plantations—allowed many overseers and planters’ sons to escape military service. Even though the provision was subsequently repealed, conscription still bore more heavily on the yeomanry, which depended on the labor of the entire family for subsistence, than on planter families supported by the labor of slaves.

In large areas of the Southern upcountry, disillusionment eventually led to outright resistance to Confederate authority—a civil war within the Civil War. Beginning in 1863, desertion became a “crying evil” for the Confederate army. By war’s end more than one hundred thousand men had fled. “The deserters,” reported one Confederate army officer, “belong almost entirely to the poorest class of non slave-holders whose labor is indispensable to the daily support of their families. … When the father, husband or son is forced into the service, the suffering at home with them is inevitable. It is not in the nature of these men to remain quiet in the ranks under such circumstances.”

Poverty, not disloyalty, this officer believed, produced most desertions. But in many parts of the upcountry, the two became intimately interrelated. In the hill counties and piney woods of Mississippi, bands of deserters hid from Confederate authorities, and organizations like Choctaw County’s Loyal League worked, said one contemporary observer, to “break up the war by advising desertion, robbing the families of those who remained in the army, and keeping the Federal authorities advised” of Confederate military movements. Northern Alabama, generally enthusiastic about the Confederacy in 1861, was the scene two years later of widespread opposition to conscription and the war. “The condition of things in the mountain districts,” wrote John A. Campbell, the South’s assistant secretary of war, “menaces the existence of the Confederacy as fatally as … the armies of the United States.”

Campbell’s fears were amply justified by events in Jones County, Mississippi. Although later claims that Jones “seceded” from the Confederacy appear to be exaggerated, disaffection became endemic in this piney woods county. Newton Knight, a strongly pro-Union subsistence farmer, was drafted early in the war and chose to serve as a hospital orderly rather than go into combat against the Union. When his wife wrote him that Confederate cavalry had seized his horse under the impressment law and was mistreating their neighbors, Knight deserted, returned home, and organized Unionists and deserters to “fight for their rights and the freedom of Jones County.” In response, Confederate troops seized and hanged one of Knight’s brothers, but the irregular force of Unionists subsequently fought a successful battle against a Confederate cavalry unit.

Outside of East Tennessee the most extensive antiwar organizing took place in western and central North Carolina, whose residents had largely supported the Confederacy in 1861. Here the secret Heroes of America, numbering perhaps ten thousand men, established an “underground railroad” to enable Unionists to escape to Federal lines. The Heroes originated in North Carolina’s Quaker Belt, a group of Piedmont counties whose Quaker and Moravian residents had long harbored pacifist and antislavery sentiments. Unionists in this region managed to elect “peace men” to the state legislature and a member of the Heroes as the local sheriff. By 1864 the organization had spread into the North Carolina mountains, had garnered considerable support among Raleigh artisans, and was even organizing in plantation areas (where there is some evidence of black involvement in its activities).

One of the Heroes’ key organizers was Dr. John Lewis Johnson, a Philadelphia-born druggist and physician. After serving in the Confederate army early in the war and being captured—probably deliberately—he returned home to form bands of Union sympathizers. In 1864 he fled to the North, whereupon his wife was arrested and jailed in Richmond, resulting in the death of their infant son. For the remainder of the war, Johnson lived in Cincinnati with another son, who had deserted from the Confederate army.

North Carolina’s Confederate governor Zebulon Vance dismissed the Heroes of America as “altogether a low and insignificant concern.” But by 1864 the organization was engaged in espionage, promoting desertion, and helping escaped Federal prisoners reach Tennessee and Kentucky. It was also deeply involved in William W. Hoiden’s 1864 race for governor as a peace candidate. Hoiden was decisively defeated, but in Heroes’ strongholds like Raleigh he polled nearly half the vote.

Most of all, the Heroes of America helped galvanize the class resentments rising to the surface of Southern life. Alexander H. Jones, a Hendersonville newspaper editor and leader of the Heroes, pointedly expressed their views: “This great national strife originated with men and measures that were … opposed to a democratic form of government.… The fact is, these bombastic, high-falutin aristocratic fools have been in the habit of driving negroes and poor helpless white people until they think … that they themselves are superior; [and] hate, deride and suspicion the poor.”

As early as 1862 Joshua B. Moore, a North Alabama slaveholder, predicted that Southerners without a direct stake in slavery “are not going to fight through a long war to save it—never. They will tire of it and quit.” Moore was only half right. Nonslaveholding yeomen supplied the bulk of Confederate soldiers as well as the majority of deserters and draft resisters. But there is no question that the war was a disaster for the upcountry South. Lying at the war’s strategic crossroads, portions of upcountry Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi were laid waste by the march of opposing armies. In other areas marauding bands of deserters plundered the farms and workshops of Confederate sympathizers, driving off livestock and destroying crops, while Confederate troops and vigilantes routed Union families from their homes. Kinship ties were shredded as brother fought brother and neighbor battled neighbor not only on Civil War battlefields but in what one contemporary called the South’s “vulgar internecine warfare.”

No one knows how many Southerners perished in this internal civil war. Atrocities were committed by both sides, but since the bulk of the upcountry remained within Confederate lines, Unionists suffered more severely. After April 1862, when President Davis declared martial law in East Tennessee and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, thousands of Unionists saw their property seized. In Shelton Laurel, a remote valley in Appalachian North Carolina, Confederate soldiers in January 1863 murdered thirteen Unionist prisoners in cold blood. Solomon Jones, the “Union patriarch” of the South Carolina mountains, was driven from his farm, forced to live in the woods, and eventually jailed by Confederate authorities. Throughout the upcountry Unionists abandoned their homes to hide from the conscription officers and Confederate sheriffs who hunted them, as they had once hunted runaway slaves, with bloodhounds; some found refuge in the very mountain caves that had once sheltered fugitives from bondage.

For Southerners loyal to the Union, the war left deep scars. Long after the end of fighting, bitter memories of persecution would remain, and tales would be told and retold of the fortitude and suffering of Union families. “We could fill a book with facts of wrongs done to our people … ,” an Alabama Unionist told a congressional committee in 1866. “You have no idea of the strength of principle and devotion these people exhibited towards the national government.” A Mississippi Unionist later recalled how the office of James M. Jones, editor of the Corinth Republican, “was surrounded by the infuriated rebels, his paper was suppressed, his person threatened with violence, he was broken up and ruined forever, all for advocating the Union of our fathers.” Jones later fled the state and enlisted in the Union army (one of only five hundred white Mississippians to do so). A Tennessean told a similar story: “They were driven from their homes … persecuted like wild beasts by the rebel authorities, and hunted down in the mountains; they were hanged on the gallows, shot down and robbed. … Perhaps no people on the face of the earth were ever more persecuted than were the loyal people of East Tennessee.”

Thus the war permanently redrew the economic and political map of the white South. Military devastation and the Confederacy’s economic policies plunged much of the upcountry into poverty, thereby threatening the yeomanry’s economic independence and opening the door to the postwar spread of cotton cultivation and tenant farming. Yeoman disaffection shattered the political hegemony of the planters, separating “the lower and uneducated class,” according to one Georgia planter, “from the more wealthy and more enlightened portion of our population.”

The war ended the upcountry’s isolation, weakened its localism, and awakened its political self-consciousness. Out of the Union opposition would come many of the most prominent white Republican leaders of Reconstruction. Edward Degener, a German-born San Antonio grocer who had seen his two sons executed for treason by the Confederacy, served as a Republican congressman after the war. The party’s Reconstruction Southern governors would include Edmund J. Davis, who during the war raised the 1st Texas Cavalry for the Union Army; William W. Holden, the unsuccessful “peace” candidate of 1864; William H. Smith and David P. Lewis, organizers of a Peace Society in Confederate Alabama; and William G. Brownlow, a circuit-riding Methodist preacher and Knoxville, Tennessee, editor.

Perhaps more than any other individual, Brownlow personified the changes wrought by the Civil War and the bitter hatred of “rebels” so pervasive among Southern Unionists. Before 1860 he had been an avid defender of slavery. The peculiar institution, he declared, would not be abolished until “the angel Gabriel sounds the last loud trump of God.” (His newspaper also called Harriet Beecher Stowe a “deliberate liar” for her portrayal of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, adding that she was “as ugly as Original sin” to boot.)

With secession, Brownlow turned his caustic pen against the Confederacy. In October 1861 he was arrested and sent North, and his paper was closed. He returned to Knoxville two years later, when Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside occupied the city. Now he was a firm defender of emancipation and an advocate of reprisals against pro-Confederate Southerners. He would, Brownlow wrote in 1864, arm “every wolf, panther, catamount, and bear in the mountains of America … every rattlesnake and crocodile … every devil in Hell, and turn them loose upon the Confederacy” in order to win the war.

The South’s inner civil war not only helped weaken the Confederate war effort but bequeathed to Reconstruction explosive political issues, unresolved questions, and broad opportunities for change. The disaffected regions would embrace the Republican party after the Civil War; some remained strongholds well into the twentieth century. The war experience goes a long way toward explaining the strength of Republican voting in parts of the Reconstruction upcountry. To these “scalawags” the party represented, first and foremost, the inheritor of wartime Unionism.

Their loyalty first to the Union and then to Republicanism did not, however, imply abolitionist sentiment during the war or a commitment to the rights of blacks thereafter, although they were perfectly willing to see slavery sacrificed to preserve the Union. Indeed, the black-white alliance within the Reconstruction Republican party was always fragile, especially as blacks aggressively pursued demands for a larger share of political offices and far-reaching civil rights legislation. Upcountry Unionism was essentially defensive, a response to the undermining of local autonomy and economic self-sufficiency rather than a coherent program for the social reconstruction of the South. Its basis, the Northern reporter Sidney Andrews discovered in the fall of 1865, was “hatred of those who went into the Rebellion” and of “a certain ruling class” that had brought upon the region the devastating impact of war.

Although recent writing has made Civil War scholars aware of the extent of disaffection in the Confederacy, the South’s inner civil war remains largely unknown to most Americans. Perhaps this is because the story of Southern Unionism challenges two related popular mythologies that have helped shape how Americans think about that era: the portrait of the Confederacy as a heroic “lost cause” and of Reconstruction as an ignoble “tragic era.”

For much of this century historians who sympathized with the Confederate struggle minimized the extent of Southern discontent and often castigated the region’s Unionists as “Tories,” traitors analogous to Americans who remained loyal to George III during the Revolution. And many Northern writers, while praising Unionists’ resolve, found it difficult to identify enthusiastically with men complicitous in the alleged horrors of Reconstruction. Yet as the smoke of these historiographical battles clears, and a more complex view of the war and Reconstruction emerges, it has become abundantly clear that no one can claim to fully understand the Civil War era without coming to terms with the South’s Unionists, the persecution they suffered, and how they helped determine the outcome of our greatest national crisis.