As he later recounted in his memoirs, Frederick Douglass endured daily beatings and forced labor before taking his chances on the road to freedom.

-

Spring 2023

Volume68Issue2

Editor's Note: Linda Hirshman is a lawyer, cultural historian, and author of several books. Portions of the following essay appear in her latest work, The Color of Abolition: How a Printer, a Prophet, and a Contessa Moved a Nation, which chronicles the fascinating alliance between the abolitionists Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Maria Weston Chapman.

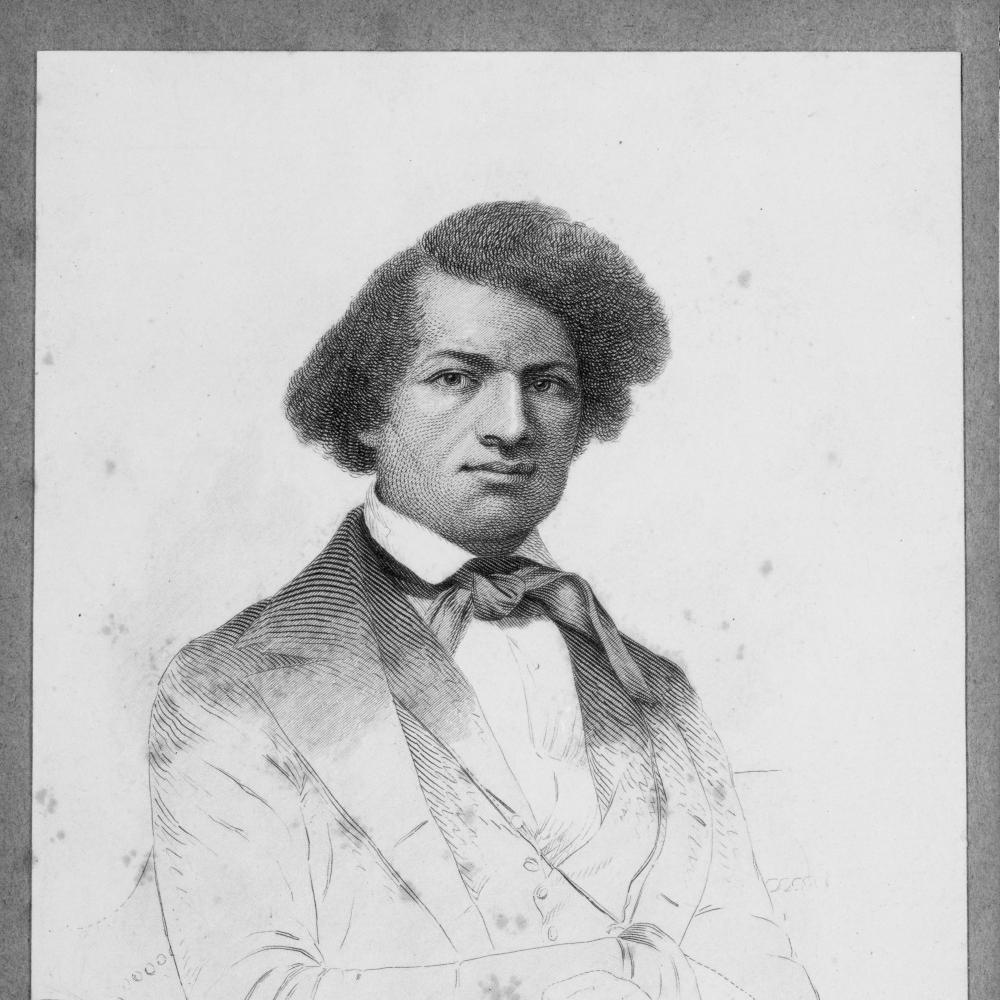

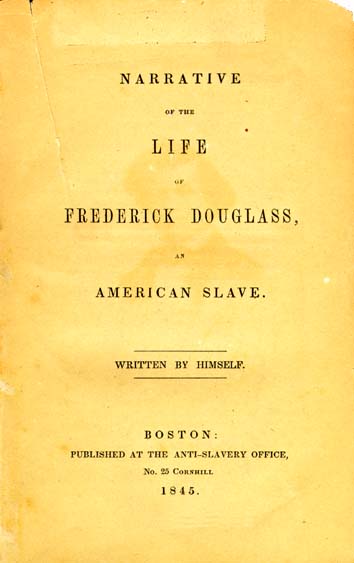

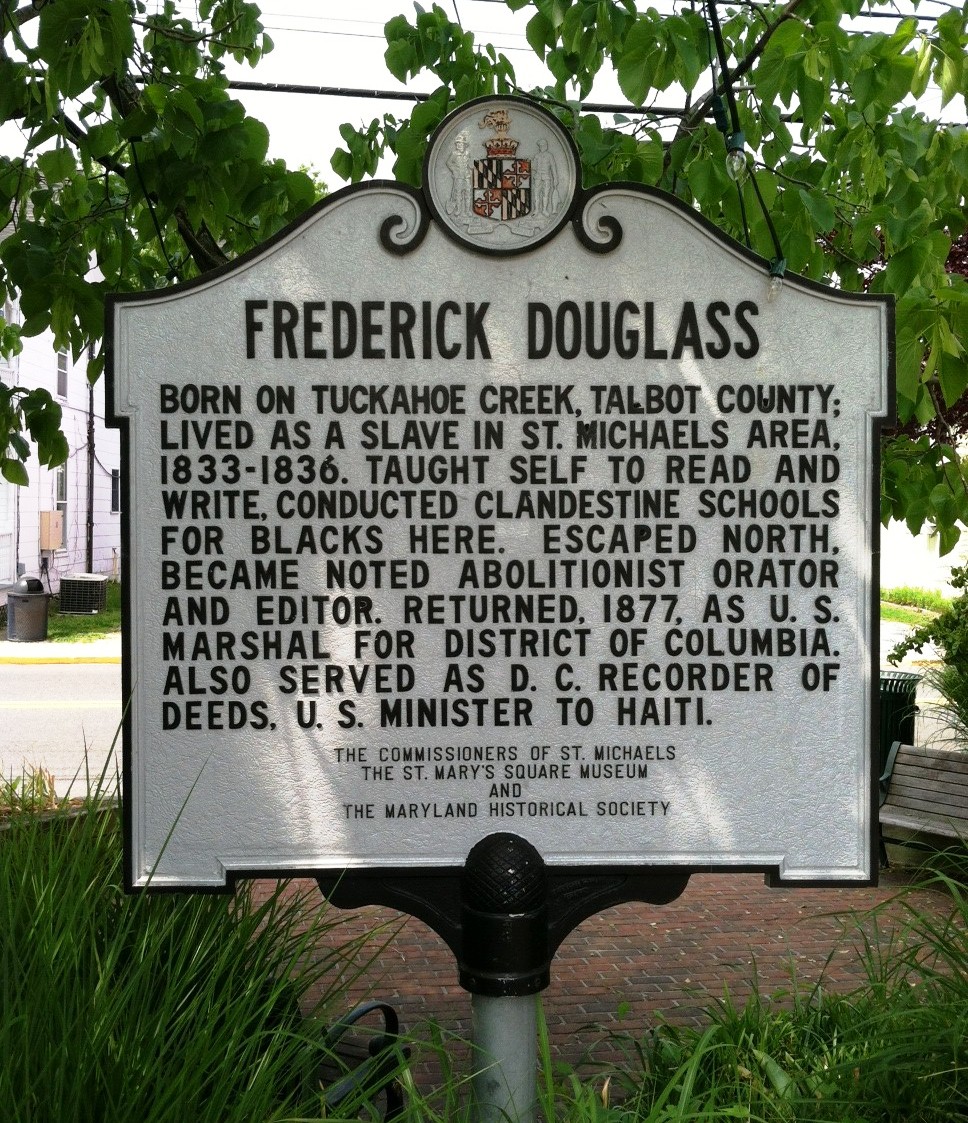

“It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away,” Frederick Douglass begins his Narrative, “to part children from their mothers at a very early age.”

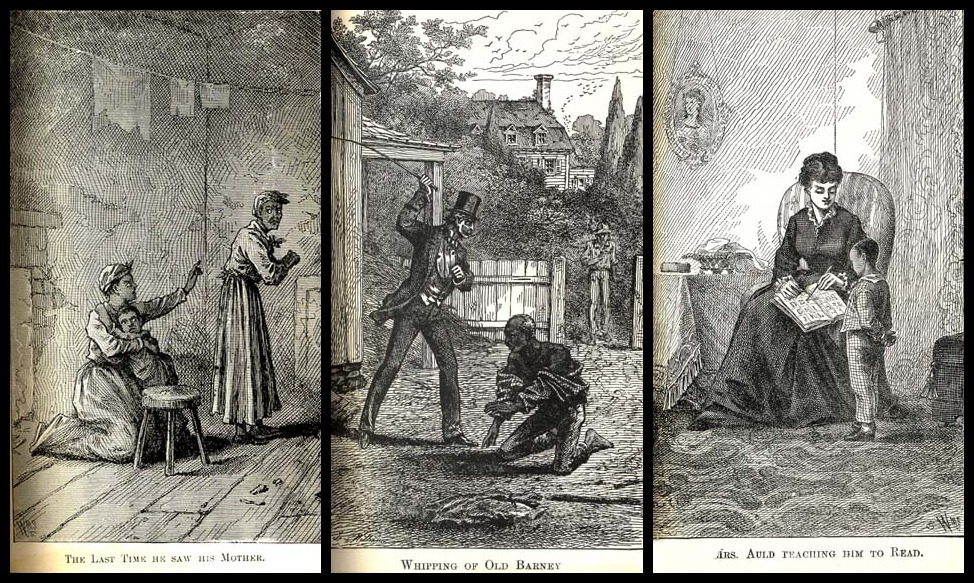

When Douglass’ mother was sent twelve miles away to work for another planter in 1819, he couldn’t have been much more than a year old. He never knew his father, who he’d heard was “a white man.” There was talk that the man was his enslaver, but of this, he says, “I know nothing; the means of knowing was withheld from me.” Douglass was lucky enough in his early years to be sent to his mother’s mother to be raised until he was old enough to be of use. During his years as a slave, he was called by his mother’s surname, Frederick Bailey; he named himself Douglass later, after he escaped. She did not live long after their parting, but he was “not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial.”

The master’s enslaved children were, Douglass astutely notes, “a constant offense to their mistress.” The master had to mollify her by treating them worse, beating them more often, and selling them to the “human-flesh mongers” who traded in slaves. Indeed, Douglass writes, the masters often acted more kindly in selling their children than in keeping them, because keeping them meant beating their own slave offspring or having their children’s white half brothers do the cruel deed to their own siblings.

Douglass had been so completely separated from his mother that he “received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.” In his second telling of his story ten years later, however, Douglass places his mother in a heroic narrative. He remembers what she looked like, he says; she resembled a drawing “in ‘Prichard’s Natural History of Man.'” Her visits to him “were few in number, brief in duration, and mostly made in the night. The pains she took, and the toil she endured, to see me, tells me that a true mother’s heart was hers, and that slavery had difficulty in paralyzing it with unmotherly indifference.”

In his second version, the 1855 memoir entitled My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass pens a maternal visit worthy of a fairy tale or the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The cruel plantation-slave cook, Katy, had cut off his rations in an attempt, she claims, to starve him into submission. As he tells it, he was suffering the extreme hunger of a day of fasting when his mother appeared for one of her rare visits. Dressing down the abusive servant, she made Douglass a ginger cake and fed him on her lap.

As with so much of Douglass’s life, it is the telling rather than the content that matters. How much more powerful than this sweet story is the brief and poignant one-sentence indictment of his separation from his mother, written in the first version, when his memory was freshest: “It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age.”

Around 1823, when he was still a toddler, Douglass’ grandmother brought him from her peaceable kingdom outside the plantation to live in the master’s house. Thereafter, Douglass was a chattel, little better than a “thing.” He was hungry and terrified by the constant threat of brutal abuse. He was sent from one owner to another like a piece of furniture. With each transfer, his life changed.

Douglass’ legal owner, Aaron Anthony, was an administrator for a huge plantation owner named Colonel Edward Lloyd. At first, when his grandmother delivered him to Anthony’s house on Lloyd’s plantation, the young boy was not worked, but he was hungry all the time. Indeed, the slaves there were so hungry that Colonel Lloyd had to tar every fence around his fabled fruit orchards to stop them from stealing the apples and the oranges. And Frederick was so cold, he later remembered, that his feet “so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.”

When Douglass was around seven, Aaron Anthony decided to send him to his son-in-law’s brother, Hugh Auld in Baltimore, to care for the Aulds’ young son. Frederick was delighted. He was eager to see Baltimore, which had mythic status on the rural Maryland plantation. When he was delivered to the Aulds at their house on Happy Alley off Aliceanna Street, Frederick saw “what I had never seen before,” he writes; “it was a white face beaming with the most kindly emotions; it was the face of my new mistress, Sophia Auld.” Douglass remembered his transfer to the Aulds in Baltimore as a manifestation of divine providence in his life. The Aulds had not owned slaves, and Sophia in particular treated Frederick like the person he was.

When Sophia started to teach her son to read, she taught Frederick, as well. If ever an act could be attributed to divine providence, it was the moment when the slave met the alphabet. Sophia had even progressed to words of several letters when, as Douglass reports, her husband, Hugh, found out what was going on. "Now," said he, "if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him.” And so, Frederick determined to learn two things: how to read and, therefore, how to pursue “the pathway from slavery to freedom.” The harder his formerly sympathetic masters tried to stop him from learning, the more determined he was to learn how to read. Frederick would not merely be a person; he would be a man of letters.

“The plan . . . I adopted,” he writes, (and) the one by which I was the most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent on errands, I always took my book with me, and by doing one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge."

Douglass knew their bread was worth more than his. As the young Douglass would say to the hungry boys: “I wished I could be as free as they would be when they got to be men. ‘You will be free as soon as you are twenty-one, but I am a slave for life!’”

This is the second place in the memoir where Douglass speaks of the occasional kindness of a white person who came across his path. He would thank these people specifically, he continues, but he was afraid he would get them in trouble for teaching a slave to read.

Because Frederick was treated as mere chattel, when his formal owner died, the Aulds were compelled to send him back to the plantation to be evaluated as part of the “inventory.” Douglass was relieved when his dead master’s son-in-law Thomas Auld sent him back to the Baltimore Aulds. Frederick had no way of knowing, but right after he arrived back in Baltimore, enslaved, William Lloyd Garrison moved a mile away, to edit the abolitionist paper the Genius of Universal Emancipation. There would be no universal emancipation in 1830, nor even the particular emancipation of Frederick Douglass. His respite was brief: a few years later, in 1832, he was sent back to the country estate to work on the farm. Formally, at that point he belonged to Thomas Auld. But Frederick was then fourteen or fifteen and had tasted freedom. And he knew how to read. Auld could not break him to rural slavery. He sent his ungovernable chattel for a year of torment to Edward Covey, a man renowned for breaking slaves.

At first, Covey seemed to succeed in breaking Douglass. Daily beatings, relentless labor, and unstinting surveillance all combined to strip him of his will. Douglass even stopped reading. Six months into his time with Covey, he fell ill. Covey kicked and beat him with a plank and left him bleeding on the ground. Douglass ran away seven miles to his legal master, Thomas Auld, to beg for release from Covey’s service, but Auld ordered him back.

When at last Frederick revealed his presence back at Covey’s, the slave breaker walked toward him with a rope to tie him up for another beating. In “the turning-point in (my) career as a slave,” instead of submitting, he took hold of his tormentor. He resisted for two hours: “My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact.”

Covey could have called the authorities and had his recalcitrant charge chained to the public whipping post and beaten without restraint. He did nothing, and he never touched Frederick again. Douglass later speculated that Covey was afraid of losing his reputation, and hence his income, as a slave-breaker.

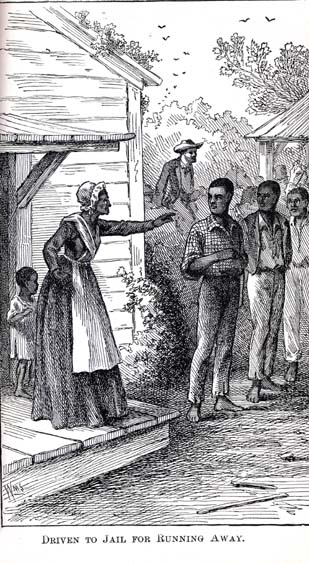

When his year was up (on Christmas Day, 1833), Frederick, unbroken, was sent to another master, one William Freeland, who was not as abusive as Covey. But as Douglass later punned, he “began to want to live upon free land, as well as with Freeland.” He made his first real attempt at escape. Gathering four other enslaved men, he plotted to steal a canoe and paddle up Chesapeake Bay to its northern end and then “follow the guidance of the North Star.” Then he proved Hugh Auld’s point: because he could write, he forged passes for the five to “go to Baltimore and spend the Easter holidays.”

Betrayed before they could even set out, Frederick and his band were arrested. The only thing he could think to do was toss his forged pass into the fire. Eat your pass, he counseled his co-conspirators as they were hustled off to jail.

Alone behind bars, Frederick contemplated his prospects, fearing he might be sold deep into the slave empire: “We had been in jail scarcely twenty minutes, when a swarm of slave traders and agents for slave traders flocked into jail to look at us and to ascertain if we were for sale. Such a set of beings I never saw before! I felt myself surrounded by so many fiends from perdition. A band of pirates never looked more like their father, the devil. They laughed and grinned over us, saying, 'Ah, my boys! We have got you, haven’t we?'”

Douglass was not sold down the river. Instead, in 1836, Thomas Auld sent the ungovernable young man back to his brother Hugh in Baltimore, who, having no need for a slave, hired Douglass out to a local shipbuilder. Douglass took to shipbuilding well, and soon, Hugh Auld was hiring Douglass out to several shipbuilders, bringing in up to nine dollars a week. The slave earned all the money, and the master took it all, sometimes tossing him a few coins as a “reward of this toil.”

After some months, Douglass managed to persuade Auld to let him function as an independent contractor, making his own deals and living on his own, not an uncommon arrangement in Baltimore. All Douglass had to do was pay Auld three dollars a week. It was a big step for the enslaved worker; he lived among the free Blacks and bondsmen in Baltimore, and he met his future wife, a free Black woman named Anna Murray. When Douglass was late bringing his weekly payment to Auld one time, and his enslaver revoked his privilege by bringing him back into the slave household, Douglass made up his mind to escape.

The key element in escape was the fugitive’s papers. In an effort to keep control of its enslaved population, Maryland, with its large community of free Blacks, had devised a system of identification papers which Blacks had to show at a moment’s notice. Brave and unselfish free Black volunteers, Douglass reported in his 1881 memoir, when emancipation was no longer a crime, would share their papers with enslaved people whom they resembled. The fugitives then would use the papers to ride the train to Philadelphia. But Douglass, a light-skinned man with a light-skinned father, could find no one who looked enough like him. Instead, he got from a sailor friend a different document, one that Black sailors used to avoid enslavement if their ships were stopped. Douglass’ sailor’s papers, whether authentic or not, had an impressive-looking eagle at the top. Someone (family lore had it that it was Anna, his free Black fiancée) made him a nautical-looking outfit.

His only problem was that he didn’t resemble the description of the sailor in the papers he carried. To minimize the scrutiny at the ticket window, a Black cabman took him right to the train, and Douglass hopped on board just as it started. When the conductor came to the “negro car,” his manner toward Douglass was markedly friendly. “He took my fare and went on about his business,” he reported, but “this moment of time was one of the most anxious I ever experienced.” And then there was still the ferry ride through slave Delaware and the train to Philadelphia and then another train to New York. In free New York, Douglass wrote, “I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.”

Frederick had a tough day or two wandering around New York, afraid to ask anyone for help or for directions, as he feared being betrayed back into slavery. “Free” soil in 1838 was anything but free, with slave catchers hunting around the border and transit places, looking for their prey. As Douglass writes in his second and third memoirs, he chanced upon a Black sailor and decided to trust him. This stranger took Douglass to David Ruggles, a Black activist and famed conductor on the real Underground Railroad in New York. A few days later, Anna arrived from Baltimore, and the two were married in Ruggles’ living room. Learning that Douglass was skilled at caulking ships, Ruggles decided that he and his new wife should settle in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a shipping town known for its hostility to itinerant slave catchers from the South. This is when the former slave named Frederick Bailey gave himself a new last name, Douglass, and left for New Bedford. He met a white man who was not a hungry lion, a Quaker named William Coffin. After hearing his story in 1841, Coffin decided that Douglass should go to Nantucket.

Not until long after the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass told the whole story of his escape. Even then, he did not say how he knew to organize such a sophisticated strategy or how he knew where to go once he got out. He thought it was unforgivable of escaped fugitives to reveal those things, since, by doing so, they would educate the slaveholder and contribute to his “facilities for capturing the slave.” Even the fabled Henry “Box” Brown, the slave who escaped by boxing himself in a crate being shipped to the North and living without food or water while en route, talked too much, according to Douglass. We might have had more boxed escapes, he asserted accusatorily in his first memoir, had Brown kept the lid on his own methods. Finally, in The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, the 1881 version of his memoir, Douglass laid out the details of his escape.