As U.S. economic power grew in the late 19th Century, nations around the world tried to emulate its success, from the European powers to Japan.

-

Winter 2026

Volume71Issue1

Editor’s Note: Sven Beckert is a professor of history at Harvard University and winner of the Bancroft Prize for his previous book, Empire of Cotton: A Global History. His recently published book, Capitalism: A Global History, is a comprehensive history of capitalism in a wide geographical and historical framework, tracing its history during the past millennium and across the world. Beckert’s research draws on archives in six continents. Portions of this essay appear in that book.

In 2016, a writer at Salon made a radical argument: Capitalism had reached a point at which “its complete penetration into every realm of being” had become a distinct possibility. No imperial or totalitarian project has ever come close to capitalism’s success at nestling into the nooks and crannies of human life. No religion, no ideology, no philosophy, has ever been as all-encompassing as the economic logic of capitalism.

In the twenty-first century, that energy continues to propel economic life. There are the almost quaint frontiers of the old-fashioned kind with commodities such as sugar, soy, tea, coffee, and oil palm. At the cutting edge are deep-sea mining and mining on celestial bodies, bringing private property rights into the world’s oceans and outer space.

Commodification – the turning of things into products that can be bought and sold on markets – pushes into yet more surprising spaces as well. Sports, for example, has been radically commodified, with soccer becoming a multibillion-euro industry where everything is for sale – players, images, clubs. Our very attention has become a commodity, too, with social media companies working to lure and hook our preferences in order to sell them.

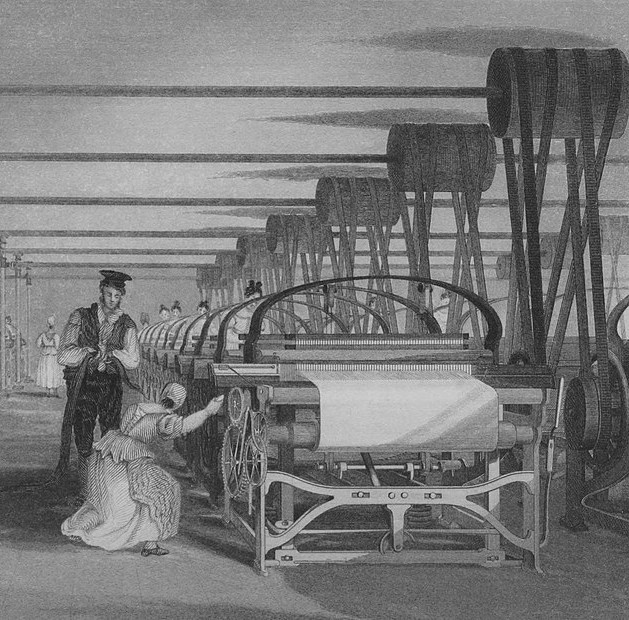

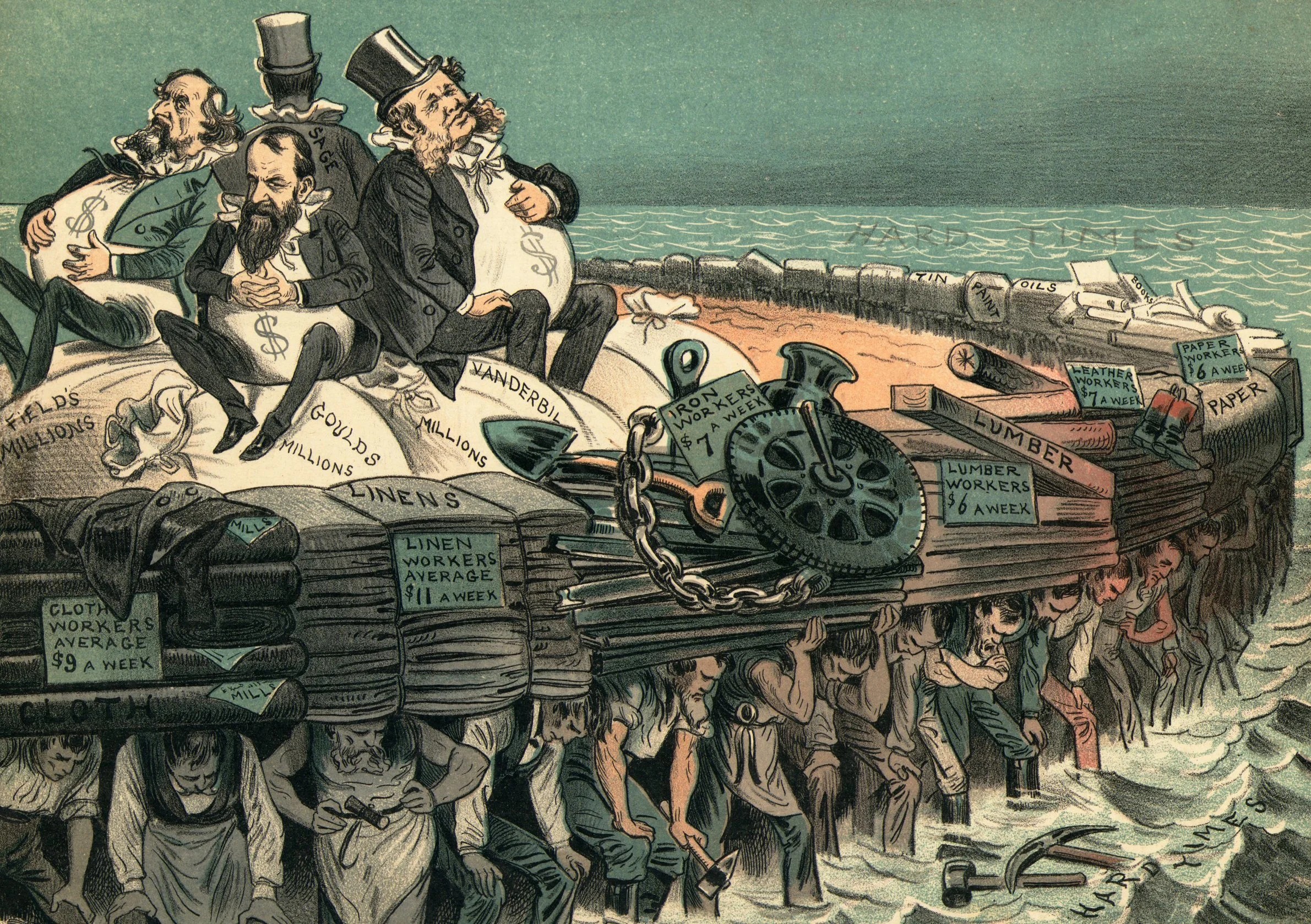

In many ways this process began in late eighteenth-century Britain when something radically new emerged: Capital owners began to locate production in factories, employing wageworkers to operate sophisticated machinery, first powered by water, later by steam. In these places, industrialists gained an entirely novel degree of control over manufacturing, one akin to what they had realized earlier on plantations. The capitalist revolution shifted its cutting edge from commerce and agriculture to industry, thus sparking the Industrial Revolution.

Before, capitalism had been a “vast but weak” system as Fernand Braudel has described it. Proto-industrialization had spread around the world, and in scattered places became full-blown industrialization by harnessing the revolutionary energy of capital to the endless possibilities of technology. Industrial capital gained tremendous strength in what historians have called the Great Divergence: the moment at which a small part of humanity concentrated in Europe became much wealthier than anyone else.

No single factor can explain the origins of the Industrial Revolution, frustrating the search for one decisive cause – institutions, the climate, labor costs, the shape of Britain’s coastlines, its access to colonies, its artisans’ inventive spirit. While all these factors mattered, they mattered more in context than on their own. Rapid, ongoing technical progress in manufacturing was essential to ushering in the Industrial Revolution, which was not the “cause” of capitalism but its consequence. No prior form of organizing economic activity had ever birthed comparable ongoing innovations along with such productivity gains and economic growth.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, new imperial enclosures – where empires or powerful states enclosed and privatized common lands to serve their own interests – formed around the globe, becoming a defining characteristic of a new capitalism. Capital’s imperial thrust – both social and geographically – took a form shaped by the powers and needs of the most fortified nation-states and the novel demands of capital owners, who had become heavily invested in immobile assets.

To European and Japanese capital owners and state officials, the United States offered a model of how capital’s envelopment into nation-states produced a new order conducive to profit and power, something they both admired and feared. Just as many Westerners of the early twenty-first century came to worry about what they called the “Chinese danger” – and tried to brake, learn from, or emulate the Chinese example in response – capital owners and state officials of the late nineteenth century fretted about the “American danger.”

This fearful envy of the United States characterized late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century debates in Europe and Japan, where industrialists, public officials, economists, and journalists warned that the United States’ “monstrous contiguous economic territories,” enormously fertile soil, and wealth of raw materials could undermine European competitiveness. The United States, French economist Louis Bose believed, would soon dominate “the universe”; the once juvenile nation had matured into a “grave menace.”

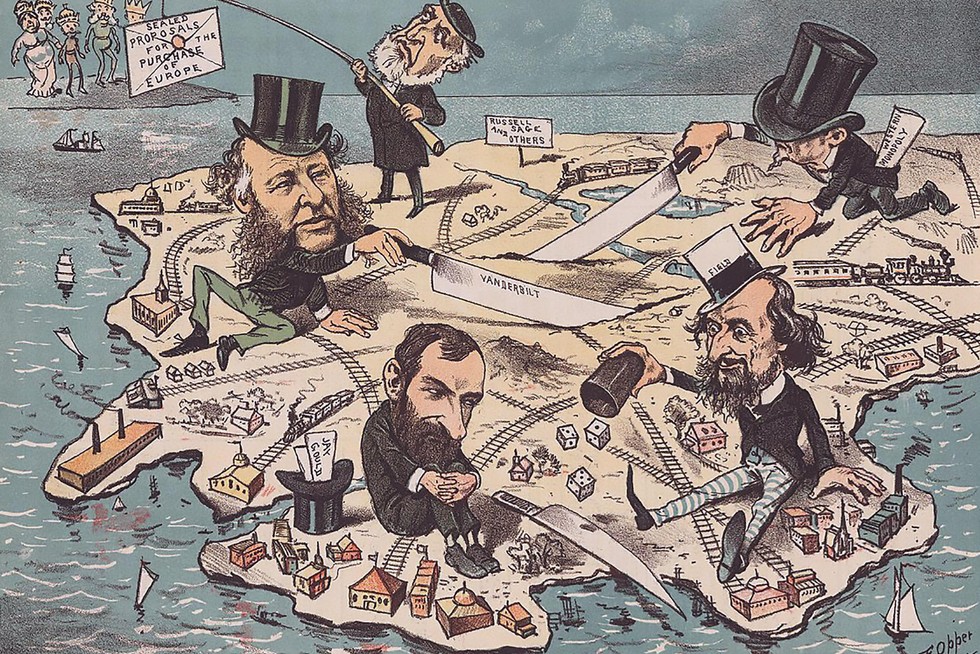

As late nineteenth-century European and Japanese observers recognized, the United States had pioneered a new form of integration of its continent-spanning national territory, with railroads, telegraphs, courts, capital, and soldiers acting in concert to consolidate access to minerals, labor, agricultural commodities, and markets. The resulting resource abundance embedded in national commodity chains was one of the primary drivers of the United States’ stunning economic performance at the cusp between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the era when mining, agricultural production, and industry fed into one another.

In the years after the Civil War, US steel output, wheat production, railroad construction, and textile manufacturing reached the top ranks of the world economy. This was the Second Great Divergence, the preamble to not only the ‘‘American Century” but also the “age of empire,” with Europe struggling to retain its global dominance. Shocked by the discontinuity that American ascendence represented, European and Japanese observers sought to emulate it, just as they had tried to emulate Britain during the original Great Divergence a century earlier.

Understanding that this new form of integration was a deeply political undertaking requiring a powerful state, they embraced similar projects. Japanese empire builders understood that the United States’ ability to secure raw materials, labor, and markets on its extensive national territory – itself a form of enclosure – was essential to its rapid economic rise. Walther Rathenau, the head of the German engineering conglomerate AEG, tellingly saw the United States as the “happiest country in terms of raw material supplies… The more industry orients itself to the world economy, the more the remotest coasts have to supply the market for raw materials, the more dangerous it becomes that we own only such a minor part of the land of the world.”

Territorial expansion had long been a key to the American economy. By 1900, the recently added states west of the Mississippi produced 65 percent of the nation’s wheat, 44 percent of its cotton, 51 percent of its corn, 75 percent of its copper, 17 percent of its coal, 38 percent of its iron ore, and 9 percent of its petroleum. The thirteen original colonies, by contrast, produced only 9 percent of the United States’ wheat, 28 percent of its cotton, 9 percent of its corn, 1 percent of its copper, 0.04 percent of its cane sugar, 43 percent of its tobacco, 13 percent of its cattle, 11 percent of its iron ore, 37 percent of its coal, and 23 percent of its petroleum. By more than tripling the size of its national territory in the first half of the nineteenth century, the US had made its agricultural and mineral resources extraordinarily abundant.

By 1913, the US produced 39 percent of the world’s coal, 56 percent of its copper, 65 percent of its petroleum, and 36 percent of its iron ore. As commodity chains broadened and deepened, the country’s precocious continental political economy let American entrepreneurs control them with relentless efficiency.

Rising American industries – textile production, steelmaking, oil refining, chemical manufacturing, food processing, telegraphy and telephony, and the new automobile industry – were built around commodity chains that were almost completely confined to the national territory of the United States. This constituted a sharp contrast to earlier eras, when coastal merchants linking American slave plantations to British factories had dominated the US economy. As American merchants and financiers aligned themselves with domestic industry in the late nineteenth century, the newly integrated national territory became crucial to them as well.

The trademark of this expansive capitalism was the intense relationship between nation-states and national capital, a relationship that required a state with new capacities to satisfy the novel demands of its spatially anchored capitalists. In North America, the two integrated and protected a national economy across a vast territory, creating an unprecedented continental economic zone largely independent of the rest of the world. Global trade was of only minor importance to fin de siècle America; between 1890 and 1914, the value of its exports was responsible for just 7.3 percent of GNP on average, and its imports equaled 6.6 percent.

The national integration of so sprawling a territory was aided by the severely lopsided distribution of military power between settlers and the continent’s Indigenous inhabitants. Equally crucial was the fact that territorial integration was one of the core missions of the American state from its founding. The government focused its expanding military resources on territorial expansion and then ensured effective administrative, scientific, and bureaucratic integration, a project that the US Constitution had set out in 1787.

An important driver here was the 1849 creation of the Department of the Interior, the American counterpart to the British Colonial Office and the French Ministère des Colonies. Instructed to “open up” the continent for private exploitation by “(s]urveying, parceling, codifying, dispossessing, disposing, settling, and utilizing land,” the Department of the Interior grew rapidly; its Indian Service branch alone grew four-fold between 1865 and 1885.

Beyond political, legal, and military mechanisms of integration and domination, the United States created an expansive free-trade zone rivaled only by that of the British Empire. The US went far beyond Britain’s vaunted navy, however, in its integration of that free-trade zone by ensuring its continuity and connectivity via an extensive continental-scale infrastructure, relentlessly pursued by an activist federal and local state and by abundant private capital – much of it, ironically, of European and Native American origin.

While Native Americans nominally received indemnity payments for dispossession of their lands, the federal government held these funds in trust and invested them in further territorial expansion. Canals, turnpikes, and railroads (first local, then transcontinental) allowed goods and people to move into the remotest corners of this territory and transported agricultural commodities and minerals to industrial enclaves and the coasts. This accomplishment was central to the nation’s self-understanding, as illustrated by late-century American anxiety over the “closing” of the frontier. By 1898, the United States surpassed its continental home, enclosing Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and, temporarily, Cuba and the Philippines, into its empire.

No other recently colonized region had been as thoroughly integrated into the national and global economy as the territory of the United States. There were other territorially expansive nations (including Russia) and energetic empires (first and foremost the United Kingdom), but none matched the economic dynamism of the United States. “The superiority of England,” argued German economist Julius Wolf, “is a matter of the past,” and the “superiority of America a matter of the present.” Territorializing commodity chains, not free trade, seemed the way to the future. And as Britain’s once extraordinary role in the world economy began to diminish, its former free-trade imperialism gave way to ever more imperial enclosures, further amplifying the “territorial” model of national economic development. Even in Britain, empire began to trump trade.

The newfound appreciation for the geographical requirements of modern economies and the desire to match American power led influential capital owners, statesmen, and intellectuals in various countries to rethink their national economic strategies. They now believed that access to cheap and reliable sources of raw materials, plentiful labor, and expanding markets were crucial for European and Japanese economies to prosper in a newly industrialized world of heavy capital investments in fixed assets.

Risking these prerequisites of industrial prosperity to global markets was unacceptable, not least because thinkers and strategists increasingly saw the global economy as a battleground of competing national units. As US naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan confidently argued in 1890 in The Influence of Sea Power upon History, for a country to be rich, it needed to trade; to trade, it required colonies; and to secure those colonies, it needed a strong navy.

No strangers to the challenges of colonial administration, European nations and Japan turned to securing American-style territorial control over minerals, agricultural commodities, labor, and markets across greater distances and a wider diversity of populations. In the last two decades of the nineteenth century, Europeans captured land on other continents that added up to more than eight times the size of Europe itself. Their new imperialism was truly global.

In 1870, only 10 percent of African territory was under European control. Thirty years later, 90 percent was colonized, with only Liberia and Ethiopia still independent. Russia moved at a rapid clip into Central Asia: Uzbekistan in 1866, northern Turkmenistan in 1873, Kyrgyzstan and western Tajikistan in 1876, southern Turkmenistan in 1885, and eastern Tajikistan in 1893. European powers, Japan, and the United States gained substantial spheres of influence in China, albeit without formally colonizing most of it. France colonized Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. This new imperialism was significantly different from the chartered companies and trading posts of earlier ages, in no small part because it was principally driven by the state, not by merchants and adventurers.

If the domestic order of the golden age was anchored within gendered and racial hierarchies, that process also unfolded in a particular set of international economic institutions. The central facet of these arrangements was the dominance of the United States in the twentieth century. The golden age was, in the words of Henry Luce, the “American Century”: If London had been the central node of global capitalism throughout the nineteenth century, New York and Washington, DC, took that role after 1945.

War had strengthened the US economy while shattering most of its peers. In 1948, the GDP of the United States was roughly twice that of France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands combined. After the war, the US produced two-thirds of global industrial output, a position no country had ever attained. US companies were by far the most productive in the world, essentially without competition. As Leon Fraser, president of New York’s First National Bank, said somewhat presciently in 1940, ‘‘As America goes, so goes the world.”

Not only did the United States produce more goods and services than any other country, it set and enforced the rules that governed the global economy. The Depression and the ensuing war had solidified elite experts’ belief that the international economy had to be put on new footing. In hindsight, it was clear that escalating economic nationalism and an utter lack of global coordination had worsened the Depression. As American secretary of state Dean Acheson put it: “We cannot go through another ten years like the ten years at the end of the Twenties and the beginning of the Thirties without having the most far-reaching consequences upon our economic and social system.” Cold War competition with the Soviet Union added urgency to US policymakers’ efforts to forge prosperity in Europe, Japan, and beyond.

As a result, the United States took the lead in hammering out a set of global, rule-based relationships and institutions – the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) prominently among them – that promoted market opening, capital mobility, and democracy. For diplomat George F. Kennan, the motives were clear: “[W]e have about 50 percent of the world’s wealth but only 6.3 percent of its population. This disparity is particularly great as between ourselves and the peoples of Asia. In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity.”

Crucially, the new economic order included a new monetary order. Designed in 1944 at Bretton Woods – a resort in New Hampshire – under the leadership of the United States, the system consisted of defined but flexible exchange rates secured by international capital controls. The gold-backed US dollar became the world’s leading currency, with all other currencies defined in relationship to the dollar. The system was overseen by the IMF, which also provided countries with loans to stabilize the global capitalist economy.

Bretton Woods steadied the value of currencies but also allowed for some flexibility should circumstances change. It restricted the international flows of capital by putting a brake on short-term and speculative investments while allowing for long-term investments, thus creating breathing space for Keynesian economic policies.