Prior to Watergate, Harding's bribery ring was regarded as the greatest and most sensational scandal in the history of American politics.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

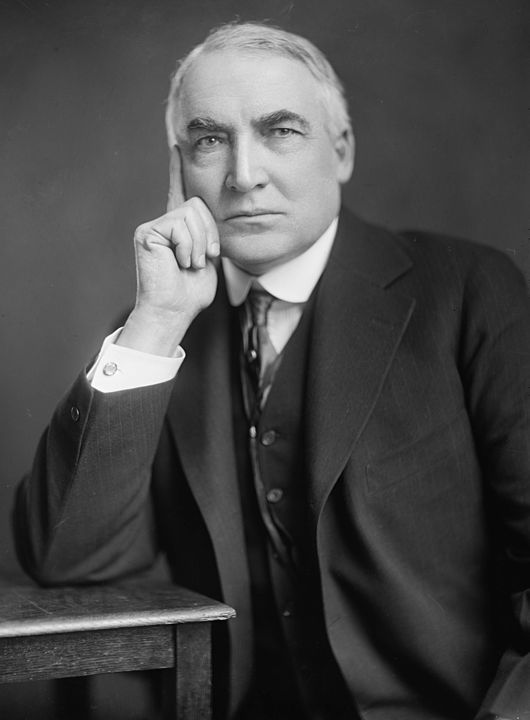

Historians have long regarded Warren G. Harding’s administration as the most corrupt in the twentieth century. Ultimately, three of the president’s appointees, including a cabinet officer, went to jail. His attorney general was tried twice by juries that failed to reach a verdict after the defendant refused to testify. The Attorney General’s closest friend and confidant committed suicide, as did the chief counsel of the Veterans’ Bureau.

In addition to these instances of corruption, the Harding administration was troubled by allegations of government by crony. Harding claimed that in selecting his cabinet he sought the “best minds,” which was undoubtedly the case in the choice of men such as Charles Evans Hughes, Herbert Hoover, and Henry Wallace.

But the cabinet also included Harry M. Daugherty, whose background made him an object of suspicion as attorney general. Daugherty, a lawyer originally from Washington Court House, Ohio, had served briefly in the state legislature during the 1890s, but his chief association with politics was through his activities as a lobbyist and his long-time friendship with Harding. The lawyer had first met Harding around the turn of the century at a Republican rally, and according to Daugherty, he immediately thought to himself, “What a President he’d make.” The relationship between the two deepened as Harding moved up in Ohio politics and Daugherty boosted him for the presidency. After serving as Harding’s campaign manager in 1920, Daugherty became attorney general.

Below the cabinet level, Harding appointed other friends to government posts. Dr. Charles E. Sawyer from Harding's home town of Marion became a brigadier general and White House physician. Ed Scobey, a one-time county sheriff and old friend, was selected as director of the Mint. Harding picked his brother-in-law, Reverend Heber H. Votaw, for superintendent of federal prisons after removing the position from the civil service lists. Daniel Crissinger, a Marion lawyer with little banking experience, was named controller of currency and, subsequently, governor of the Federal Reserve Board.

At the time these appointments attracted little attention, but they were later cited as evidence of Harding's questionable standards, despite the fact that most of his friends in government were never implicated in any wrongdoing.

Teapot Dome and the Origins of the Investigation

In April, 1922, rumors reached Senator John Kendrick of Wyoming that the government had secretly leased private drilling rights for Naval Oil Reserve Number Three, known as Teapot Dome. Kendrick asked the Interior Department for information and was told on April 10 that no contract for a lease had been made. Four days later the Wall Street Journal reported that the Interior Department had leased Teapot Dome to Harry Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Company. Kendrick then introduced a resolution in the Senate calling for “all proposed operating agreements” for the Teapot Dome, and the Senate adopted the resolution on April 15.

Three days later the Interior Department formally announced the leasing of the entire Teapot Dome oil reserve and indicated that an additional lease would be awarded for parts of California reserves to Edward L. Doheny’s Pan-American Petroleum and Transport Company. On April 21 the Department of the Interior complied with the Kendrick resolution by sending the Senate a copy of the contract with Sinclair’s company.

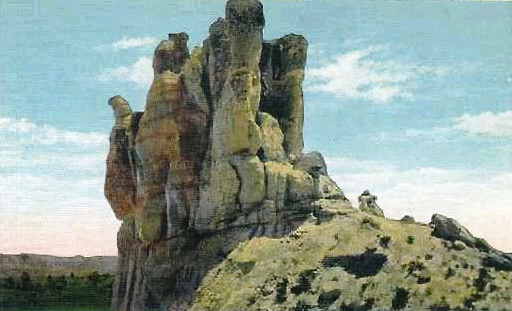

A long history of government oil policy lay behind Teapot Dome, the name associated with the worst scandal of the Harding administration. In 1912 President William Howard Taft had created the first two naval oil reserves, encompassing over 60,000 acres, at Elk Hills and Buena Vista Hills in California. Taft had acted after receiving warnings from conservationists and scientists that unrestricted tapping of petroleum could lead to critical shortages in the future. Three years later President Woodrow Wilson set aside almost 10,000 acres of oil-bearing land in Wyoming for the exclusive use of the United States Navy. This Naval Oil Reserve Number Three was called Teapot Dome because the oil dome lay under an outcropping of rock shaped like a teapot.

Although conservationists strongly supported the policy of petroleum reserves, oil men and many westerners continued to fight for private development of natural resources on all public lands. In part as a result of this pressure, Congress passed the Oil Land Leasing Act of 1920, which permitted the government to lease private drilling rights on public lands.

Moreover, the country’s three naval oil reserves were included in the law in order to allow the tapping of government petroleum to prevent drainage into neighboring private lands. Another law adopted in 1920 gave the secretary of the navy control over the three reserves “to conserve, develop, use, and operate the same in his discretion, directly or by contract, lease or otherwise.”

Early in the Harding administration, the Navy Department relinquished its jurisdiction over the naval oil reserves. In an executive order dated May 31, 1921, the president transferred the reserves to the Interior Department. According to a public announcement, Harding acted at the request of both Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall and Navy Secretary Edwin L. Denby. Fall, a New Mexican who had previously served in the Senate, had long favored expanded private development of the country’s resources, and he had clashed before with conservationists. In July, 1921, Fall awarded the first drilling contract to Edward Doheny for offset wells at the Elk Hills reserve, but this lease generated little criticism because it resulted from publicized competitive bidding and served to prevent drainage.

After the revelation of additional leases in April, 1922, conservationists sought a full Senate inquiry. Although they had no evidence of any wrongdoing, conservationists distrusted Fall, and several of them persuaded Senator Robert M. La Follette to introduce a resolution authorizing the Senate Committee on Public Lands to investigate the entire subject of leases on naval oil reserves. The Senate adopted the La Follett resolution by a unanimous vote on April 29, 1922.

In response to the resolution, which called for all material in the Interior Department files concerning the leases, Secretary Fall sent a truckload of documents to the Senate in June, 1922. In a letter of transmittal accompanying the records, President Harding declared that the oil policy of Fall and Denby “was submitted to me prior to the adoption thereof, and the policy decided upon and the subsequent acts have at all times had my entire approval.”

Public hearings on Teapot Dome, which ultimately produced evidence that sent Albert Fall to jail, did not begin until 16 months later, in October, 1923. By that time, Fall had resigned from the cabinet, and Harding had died. When Fall left the Interior Department in March, 1923, his name was still untarnished. Harding was probably unaware that Fall had done anything wrong.

Allegations about Harding after His Death

On August 2, 1923, President Harding died in San Francisco while on a tour of the West. Americans turned out by the millions to mourn Harding as his funeral train crossed the country to Washington and back to Marion, Ohio, where he was buried. At the time, people could pour out their grief for a beloved president because there was little reason to question his integrity. One observer recollected that “the country thought of Harding as a capable and deserving President who had died mid-term of a worthy administration.” Only later would investigations gradually reveal the extent of previously undetected corruption within the administration.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.