Nixon’s abuse of presidential power constitutes his most important influence on later constitutional law and U.S. politics.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

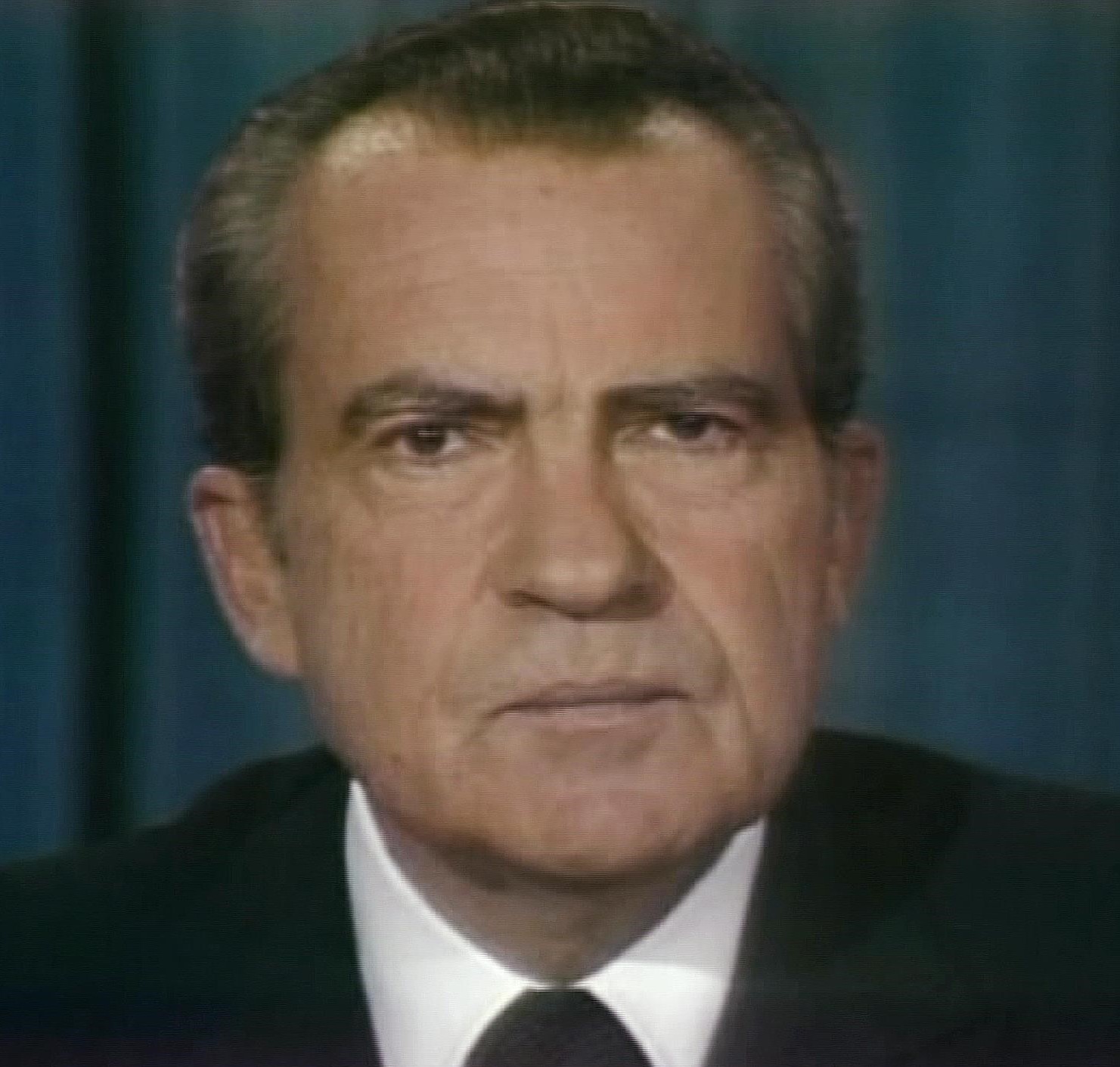

Richard M. Nixon ran for the White House in 1968 as someone long familiar to American voters as the Republican Congressman from California who attacked Alger Hiss as an agent of the Soviet Union, as the Senator who won office by claiming his opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas, was “pink down to her underwear,” and as the dour vice president to the smiling Dwight D. Eisenhower (as well as a losing candidate for the presidency and the California governorship.) He ran as a “new Nixon,” a man who had matured out of his old roles of Red-baiter and attack dog, a once-fierce Cold Warrior who now promised “an honorable end to the war in Vietnam.”

In pursuing that campaign promise, Nixon reverted to his old ways even before winning office by seeking to ensure that the outgoing administration of Lyndon B. Johnson would fail in its efforts to negotiate its own peace treaty to end the war in Southeast Asia. Once in office, Nixon — without congressional warrant — first secretly and then openly expanded the Vietnam War into neighboring Cambodia.

In the face of growing protest and in response particularly to military analyst Daniel Ellsberg’s unauthorized release in 1971 of the Defense Department’s internal studies of the Vietnam War (the series of documents better known as “the Pentagon Papers,” which revealed the analysts’ conviction that the war could not be won), Nixon established a team of operatives devoted to stopping such leaks by criminal means. Throughout the Nixon administration, recourse to illegal behavior became not only an available option but central to the president’s conception of the office of chief executive of the United States.

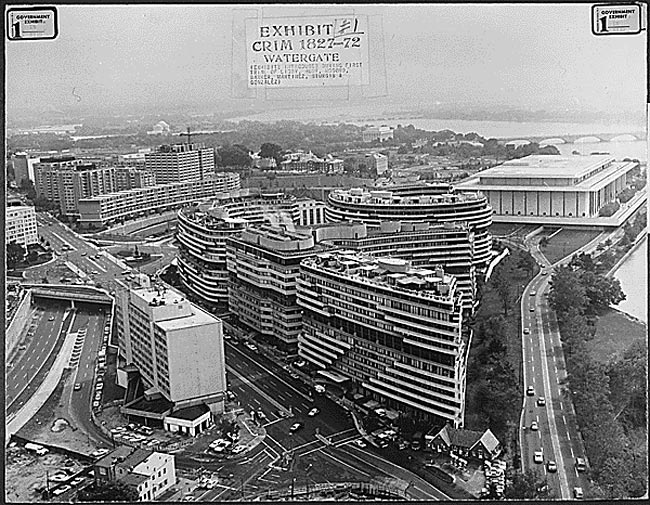

Watergate Break-In, Cover-Up, Exposure

In mid-June 1972, police discovered evidence of one part of the Nixon administration’s many illegal programs. The break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in a Watergate complex office building that day was actually the second Watergate burglary. The first occurred in late May 1972, when a team of former CIA agents secretly entered DNC headquarters and placed wiretaps on two phones. When one of the taps failed to work and perhaps also to search for documents that could damage or help Nixon’s campaign, the team returned to replace the defective wiretap.

During the burglars’ second trip, a security guard discovered evidence of the illegal entry and alerted the police. Reporters jumped on the story when they realized that one of the burglars was James W McCord, Jr., the chief of security for the CRP, although Press Secretary Ronald L. Ziegler dismissed the incident as a “third-rate burglary attempt.”

Nixon and his advisers immediately understood that if they let the investigation proceed, their many illegal activities would be revealed. They thus embarked on a cover-up, seeking to delay or altogether stymie an investigation lest it reveal the creation of the Plumbers, the break-in at Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office, the Huston Plan, the Cambodia wiretaps, the Enemies List, the espionage and sabotage efforts against several Democratic presidential candidates, the bribery and extortion committed by the campaign’s fund-raisers, and other embarrassments. To avoid exposure, Nixon and his aides began to consider how to foil investigators and ensure that the burglars refused to cooperate with prosecutors.

On June 23, 1972, Nixon met with Haldeman to discuss how to handle the break-in. The White House taping system recorded the president ordering Haldeman to use the CIA to pressure the FBI to drop its investigation.

Nevertheless, the FBI continued its inquiry, and one bureau official, Associate Director W. Mark Felt began to leak information about the inquiry to the Washington Post. The Post’s reporters, especially Carl Bernstein and Robert U. “Bob” Woodward, who would soon be celebrated for their coverage of the entire scandal, dubbed Felt “Deep Throat.” His leaks kept the story alive in the press. The president, however, stated categorically that “no one in this administration, presently employed, was involved in this very bizarre incident.” A federal grand jury indicted the five burglars, Hunt, and Liddy, but no other administration officials.

In January 1973, the trial of the “Watergate Seven” opened in federal district court in Washington. Although the defendants continued to play along with the cover-up during the trial itself, the presiding judge, John J. Sirica, doubted that the trial had exposed the real truth about Watergate. He threatened the defendants with long prison sentences if they did not tell all they knew. McCord then shocked the court and the rest of the country by writing a letter to Sirica claiming that the witnesses had perjured themselves and that unidentified “others” were involved in the Watergate conspiracy. After McCord chose to reveal his role in the cover-up, other conspirators soon followed.

Senate Democrats and Justice Department lawyers insisted that Nixon’s incoming Attorney General, Elliot L. Richardson, appoint a special prosecutor to investigate the break-ins and cover-up, and they forced Richardson to promise that he would fire the prosecutor only if there were “extraordinary improprieties on his part.” Richardson chose Archibald Cox, Jr., a Harvard Law School professor who had served as Solicitor General in the Kennedy administration, as Special Prosecutor.

In addition, the Senate established a select committee to investigate any “illegal, improper, or unethical activities” that occurred during the presidential election of 1972. The committee’s nationally televised hearings would command the nation’s attention.

The most dramatic moment in the hearings came when Alexander P. Butterfield, Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman’s chief assistant, revealed in July 1973 that Nixon had been taping conversations in the White House since early 1971. The voice-activated tapes could potentially prove whether the president was telling the truth about the Watergate cover-up — or, in other words, what the president knew and when he knew it, in the memorable phrase of Republican Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr., of Tennessee.

The Senate Watergate Committee subpoenaed several tapes — the first time in history that Congress had issued a subpoena to a president. Cox also issued his own subpoenas.

Entering battle with the Senate Watergate Committee and Cox over control of the tapes, the President resisted these subpoenas. He claimed that he could withhold the tapes on the grounds of executive privilege. Cox, however, insisted that the tapes contained evidence of crimes and therefore must be turned over to investigators.

Nixon proposed a compromise in which Senator John C. Stennis, a conservative Mississippi Democrat known to be hard of hearing, would listen to the audiotapes and report on their contents. When Cox declined this dubious compromise, Nixon decided to fire him. Attorney General Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William D. Ruckelshaus resigned rather than carry out the President’s order. Ruckelshaus advised Solicitor General Robert H. Bork, the next in command at the Justice Department, to carry out the President’s order “if his conscience would permit." It did; Bork finally fired Cox, and the press dubbed the episode the “Saturday Night Massacre.” The incident galvanized opposition to the President, as newspaper editorial boards around the country called for his impeachment or resignation. Public support for impeachment doubled to 38 percent.

The President suffered other reverses and accusations of misconduct in the fall of 1973. Vice President Spiro T. Agnew was forced to resign after he pleaded no contest to charges of accepting bribes and failing to pay taxes on those bribes as Governor of Maryland. Members of Congress also raised questions about Nixon’s personal finances. He had made questionable, backdated deductions on his tax returns which allowed him to avoid hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes.

The scandals regarding Nixon’s personal finances were not directly related to the story of misconduct in the 1972 election, but revelation of them in the middle of the Watergate investigation contributed to the growing consensus that the President could not be trusted.

In March 1974, the federal grand jury investigating Watergate crimes indicted seven top presidential aides, including Haldeman and Mitchell, along with more than thirty other people. Ultimately more than forty individuals associated with the Nixon scandals would plead guilty or be convicted of crimes. Jaworski asked the jury to name Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator, rather than charge him with crimes, because the prosecutor doubted that a president could he indicted while in office. An impeachment process should be finished first, he believed.

As Jaworski continued to demand more tapes, the president offered another compromise. Instead of releasing all the actual tapes, he would give the special prosecutor edited transcripts of some of them. In April 1974, he announced his delivery of these transcripts in a nationally televised address in which he was flanked by stacks of blue notebooks representing the conversations. Rather than ending the controversy as Nixon had hoped, the transcripts only emboldened the President’s critics.

The transcribed conversations quickly became a cultural phenomenon. Some television and radio shows staged dramatic readings, newspapers ran them as special inserts, and paperback editions sold over a million copies. The transcripts laid bare the vulgarity of the Oval Office conversations, with “expletive deleted” becoming a Watergate catchphrase.

Impeachment Debate and Resignation

The House Judiciary Committee began to consider articles of impeachment against Nixon in May 1974. After a brief public session, the committee met behind closed doors for the next two months as its members studied the massive factual record of Watergate that had been prepared by the committee’s staff members. As they read through the documents, seven Southern Democrats and moderate Republicans — soon dubbed the “fragile coalition” — began to support removing Nixon from office. The President tried to demonstrate his mastery of foreign policy by embarking on a major diplomatic journey in June 1974, traveling to Egypt, Syria, Israel, and the Soviet Union. But critics argued that he was just trying to distract Americans from Watergate, and momentum for impeachment continued to build.

On the committee’s first day of public deliberations on impeachment, July 24, 1974, the Supreme Court announced its unanimous ruling that Nixon must turn over all the subpoenaed tapes to the special prosecutor. Without knowing the content of those conversations, the committee members began to debate and vote on articles of impeachment. Strong majorities approved articles for obstruction of justice (27-11) and abuse of power (28-10). A third article on contempt of Congress also secured a majority (21-17). One-third of all committee Republicans voted for at least one of the three articles.

Articles that the committee considered on the secret bombing of Cambodia and Nixon’s failure to pay his taxes did not win majority support. The decision by some Southern Democrats and moderate Republicans to vote for impeachment signaled that a majority of the entire House would almost surely follow suit. But Nixon still had a chance of retaining the support of one-third of the senators, which was all he needed to stay in office. Even at this late date, some Republicans—mostly conservatives who saw Nixon as a victim of the “liberal media” — fiercely defended the President.

Nixon’s support all but evaporated on August 5, when the White House released the transcripts of the other subpoenaed tapes, including one that Nixon had thus far withheld even from his own lawyers and top aides. The tape recorded on June 23, 1972, provided what became known as the “smoking gun”: evidence that the president had been involved in the Watergate cover-up from the beginning. The entire country could now read how the president and Haldeman had tried to use the CIA to end the FBI investigation of the Watergate break-in.

The revelation of the smoking-gun tape destroyed the president’s last chance of staying in office. Even his strongest defenders on the House Judiciary Committee said they would support impeachment for obstruction of justice, and key Republican senators said they would vote to convict. On August 7, a delegation of prominent congressional Republicans led by Senator Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona visited Nixon in the White House and told him that he would almost certainly be removed from office if the Impeachment Inquiry followed its likely course.

To avoid impeachment and removal, on August 9, 1974, Nixon re-signed, the only president in American history to do so. Shortly before he boarded a helicopter to depart the White House, he delivered an impromptu speech to staff in which he offered, perhaps inadvertently, a clear summation of the reasons for his downfall. “Always remember, others may hate you,” he said, “but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.”

Copyright © 2019 by The New Press. Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.