Life at an office that was not quite an embassy

-

August/September 2005

Volume56Issue4

Twenty-five years later, I still find them turning up: small ceramic pandas, nail clippers bearing the logo of the People’s Republic of China airline, handsome lapel pins with a golden profile of Chairman Mao. I collected them all while commuting from Hong Kong to Beijing in the late 1970s, when there was no American Embassy there, just a small diplomatic enclave called a Liaison Office.

At the time, long before the deluge of tourists and traders was allowed into “Red China,” there were no direct flights between the two cities. You traveled the 40 miles to Canton by train or hovercraft and then continued by plane to Beijing. On the flight, a cheerful attendant in a baggy uniform made her way down the aisle pouring tea from a large, dented, blackened kettle. She would return with your snack—stewed chicken feet or pickled cabbage—and the keepsakes.

The U.S. Liaison Office in Beijing was a drab two-story structure about the size of a Denny’s restaurant. It did not look like the product of secret meetings between some of the towering figures of the 20th century. On a trip to Pakistan in July of 1971, Henry Kissinger disappeared for a weekend to meet with Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing. In 1972 came what a Tokyo paper I read called the “Nixon Shokku” (the Nixon Shock). Incredibly, Nixon and Mao Zedong had agreed to work toward a normalization of relations. At a follow-up meeting in February 1973, Zhou invented the concept of the Liaison Office, which would allow a handful of American and Chinese nationals to work in each other’s capitals before full diplomatic relations could be established.

Thus, two not-quite embassies opened, both governments sending them some of their most talented diplomats. These pioneers were to struggle for years in a bureaucratic no-parking-zone, spied upon by their host governments.

Although I was not employed by the State Department, I commuted to the Beijing U.S. Liaison Office for a couple of years when I was working for the now-defunct U.S. Information Agency. The State Department worked under the premise that the best way to get along with communist countries during the Cold War was by letting them learn as much as possible about our culture and the workings of democracy. My job was to help Chinese librarians, long isolated from all things Western, to gain access to information from the States.

I stayed at the century-old Peking Hotel, its stolid facade hiding scars from the Boxer Rebellion. The hotel had been renovated in the 1950s and a new Soviet-style wing added on, but it was always stuffed with members of the USLO awaiting quarters, with entire families often jammed into a single room for months. My friend Bill Stubbs recalls joining a newly arrived political officer and his wife for drinks. To avoid waking their sleeping children, they sipped their martinis sitting on the floor in the corridor outside their room.

You were never in danger of losing your hotel key; you never got one. A floor attendant stationed at a desk at the end of the corridor would open your door to let you in and lock it when you went out.

That, of course, left the door unlocked when you were in the room, and most doors had no inner bolt. Hotel staff could walk into your room at any time. Sandy Roy, the wife of Stapleton Roy, the deputy chief of the Liaison Office, remembers an occasion when a young female hotel employee walked in on a man, naked, heading for a bath. She shrieked, he yelled, the manager arrived. “The guest was furious at the intrusion,” Sandy said, “but the manager took the employee’s side and chewed out the guest for having embarrassed an innocent young woman.”

Unlocked doors may have threatened privacy, but they didn’t seem to affect security. I could leave my camera or a cash-stuffed wallet in my room, confident that they would be undisturbed. More than once when I was checking out, an attendant came running to give me back a discarded toothbrush or an odd sock.

Although the Americans at the Liaison Office never doubted their mission’s importance, it wasn’t always apparent to outsiders. The chief and the deputy chief had to share in entertaining visiting dignitaries, but their wives couldn’t stage a dinner party on the same night because there was only one set of formal dinnerware. And the official car was a black-painted Kalamazoo-made Marathon Checker cab. When George H. W. Bush became chief in 1974, he lobbied for a more imposing vehicle, but the State Department allocated perks by the rank of the embassy, and “USLO Peking,” as State Department cables then labeled us, was at the bottom of the heap. Exasperated, Bush reportedly gave up the fight and wired: “Send Checker; remove meter.”

Driving in Beijing could be hair-raising. The wide streets of the city were often curb-to-curb bicyclists, hundreds and even thousands of them hell-bent on getting to work or back home. Maneuvering through town, we became accustomed to seeing amazing things strapped to the bikes: wheelchairs, desks, small sofas, lumber, and the occasional full-grown pig in a custom-fit rattan cage.

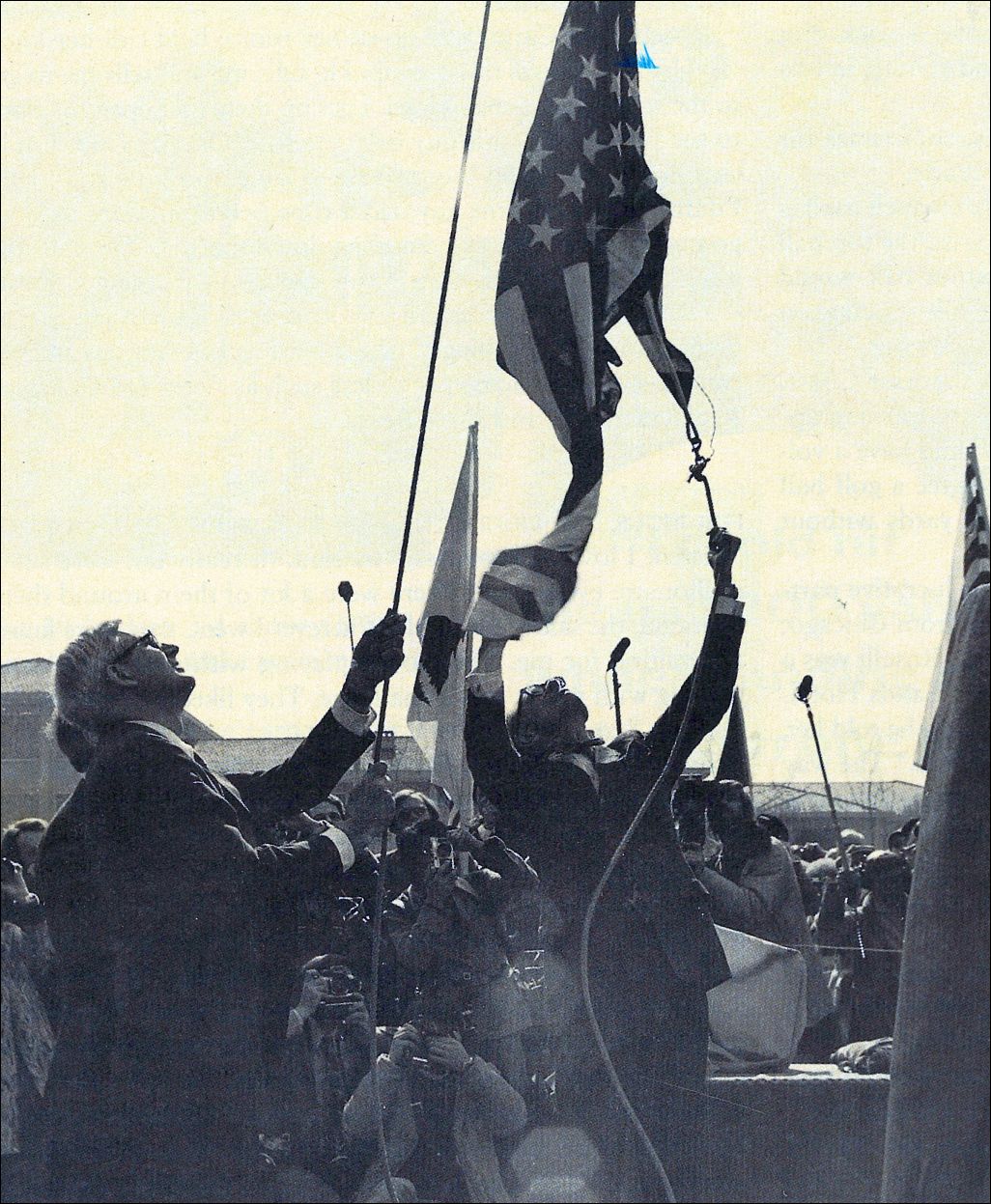

After almost six years of diplomatic limbo, the day came to take down the sign for the Liaison Office and put up one that read United States of America Embassy. Three rows of blue-coated Chinese pressed against the fence of our compound; we were still forbidden foreign territory to Beijing’s residents. Stapleton Roy introduced President Carter’s envoy, Secretary of the Treasury Michael Blumenthal, who addressed the crowd in Chinese, a language he had learned as a teenage factory worker in Shanghai as a refugee from Nazi Germany.

Minutes before noon on March 1, 1979, 14 children, arms dangling from long-outgrown jackets, faced the small crowd. At a signal from their teacher, their voices washed over the compound, “… for spacious skies, for amber waves of grain… .” Their soft singing of those words touched us all.

Strings of firecrackers exploded, sending smoke over refreshment tables holding hard-to-come-by Cokes. Two men struggled to lower the mission’s old flag, which had gotten tangled in its ropes. Stapleton Roy, destined to return as ambassador, snapped a new flag onto the halyard, and we watched it rise, the first to fly over an American embassy in China in nearly 30 years.