The author took part in the first night combat with Japanese bombers. In that dramatic action, he witnessed the loss of Butch O'Hare, the famous World War II ace for whom O’Hare Airport was named.

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

By 1943, the war was moving fast—new carriers, new airplane squadrons—and in November our air group, commanded by Lt. Comdr. Edward “Butch” O’Hare, was loaded aboard ship for the Pacific Theater. O’Hare was a hero of the early war, having shot down five Japanese planes in one day and probably saving the carrier Lexington at the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Our task force was sent to the Gilbert Islands, where the Marines were in a bloody fight at Tarawa. The Japanese had big airfields several hundred miles to the north in the Marshalls out of which they were flying medium bombers, known as “Bettys.” Loaded with torpedoes, they would fly down and try to find the American fleet, hoping to sink a carrier or two. It was decided to do something about them, and Admiral Arthur Radford, commanding the task force on the carrier Enterprise, in consultation with Butch O’Hare and our squadron commander, Lt. Commander John Phillips, devised the first ever night-fighter operation off carriers, code-named “Black Panther.”

A few small airborne radar sets had been issued to the fleet a year before, but they were not yet in general use. Primitive instruments with a small green screen about five by seven inches, they had a sweeping arm that briefly lit up as it crossed the location of other planes—terribly difficult to read—with a maximum range of about ten miles, and precise only much closer. Still, having seen nothing like them before, they impressed us mightily. When lost, you could also find your way back to a ship with one of these, instead of flying into the empty ocean until you ran out of gas. Sets had been installed into two of our torpedo planes by a specialist, Lt. (junior grade) Hazen Rand, who had worked in the development of the airborne naval radar sets at M.I.T. After a crash course in operating the rear gun, Rand replaced our navigator for the Black Panther Operation.

On November 24 at about 0500, while we were circling looking for targets, there was a huge flash of light off to the east, like the sun rising, which we later learned was the escort carrier Liscombe Bay blowing up when hit by a Japanese submarine torpedo. She was a light carrier with pitifully little protection, and everything in her—gasoline, bombs, torpedoes—blew up at once. She went down instantly, with the loss of more than six hundred men.

Then, on the night of the twenty-sixth, the new night-fighting scheme was put into action again using two fighters and a torpedo plane. One of the fighters was to be flown by Butch O’Hare and the other by his wingman Ensign Warren Skon. The torpedo plane was inevitably flown by Phillips as squadron commander. Rand was in the tunnel again, while I remained, somewhat unsure about all this, as the gunner in the turret. The fighters and the torpedo plane were to go off together, early in the evening if the Japanese appeared then, and—here was a big risk—we would all have to land on the carrier deck in darkness, without lights. The barely secured landing field at Tarawa had been requested to receive us if we could not get back to the carrier.

Japanese snoopers were already in probing the fleet before sunset, and fighters from the Belleau Wood shot down one Betty. Sitting in the ready room below the flight deck, we wore red goggles to keep from being blinded when we went into the dark. As dusk was falling, the public address system told us that a large number of Bettys had been picked up on radar on a bearing that would lead them to the ships. A few moments later came that stirring command, “Pilots, man your planes,” and the two fighter pilots, Phillips, Rand and I made our way up to the flight deck and into our planes. I checked and double-checked all the guns on the torpedo plane.

The two fighters went off first, at 1800, fired from the catapult, and disappeared into the distance, small diminishing blue lights just visible from their exhaust flares. We went off next. Heavily laden torpedo planes always sank below the deck when fired from the catapult, and looking from the backward-facing turret. I could see the huge black deck rise above us and feel the tug of the waves below. But the engine at full power pulled us up and away, and as the wheels and flaps came up we mined altitude in the darkness and began to move away from the white wakes and bow waves of the task force while waiting for the fighters to join up on our wings.

From the beginning, the fighters were far ahead of us, hoping to catch a snooper before dark closed in, and we fell farther and farther behind. Since we depended on the fighters for protective firepower, I assumed we would go back to the ship once we lost them.

But Phillips was an aggressive naval aviator, and after a time he decided to strike out for himself. We flew about for a time while the fighter director officer tried to get all our planes together, but still no fighters. Then Rand called out that he had a contact on his radar. Four, five, ten, then twelve. Two parallel rows of six Bettys each. We swung in behind them, and Rand began calling out the range: three miles, two, one, a thousand yards. Then, at two hundred yards, the pilot confirmed, “I have them in sight. Attacking.”

This seemed madness to me, our lightly armed, clumsy, slow torpedo plane attacking twelve bombers in a tight mutually supporting formation, each with five guns—front, rear, top, two in the waist—but nobody asked for a vote, and the plane banked up and to port, then swung in high on an angle toward the rear Betty in the starboard line. The two .50-caliber guns firing in the wings felt like they were tearing the plane apart.

It all developed so fast that training took over from thinking. As we tilted up and away from our firing run on the first plane, I could look back and see the surprised enemy opening up from his top turret, his blister gun, and his tail, the heaviest and most accurate fire coming from the 20-mm in the tail. Fire flared out from his wing where the gas tanks were, and I began firing at the flames. He blew up all at once. A long trail of fire went down and down into the blackness of the ocean below, where it kept burning, a red smear on the black water.

The Japanese were totally confused. Night fighters off carriers were as unknown to them as they were to us, and the night was filled with so many tracer beams it was impossible for them to tell where the attacking plane was. In their excitement the Japanese gunners were firing into their own planes in the opposite line.

The Japanese firing was disorganized but not entirely harmless. We turned away from the burning plane and started into a firing run on another. I fired back into the first plane as it glided down toward the water to crash and burn. Just then, Rand called out on the intercom. “I’m hit.”

I unlatched the armor plate below me and crawled into the bucketing plane to sit on the green aluminum bench beside Rand. A pale, thin-faced man anyway, his face in the ghoulish green light of the radar screen was now a skull. A single bullet had come through the plane just forward of the armor on the floor where his foot had braced while he peered into the radar scope, and it had torn off the side of his shoe and foot. It wasn’t a mortal wound, unless he bled to death, but it was sure a painful mess. I called Phillips on the intercom. “Shall I give him an injection of morphine?” (We carried Syrettes in the medical kit.) The answer shocked me. “No, we will need the radar again.” The logic was obvious, though I didn’t think Rand was going to do much more work that night.

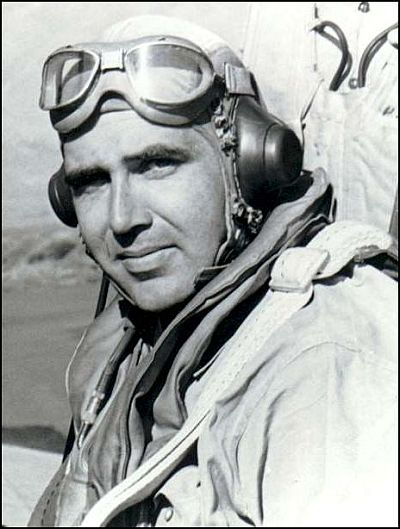

The ship’s radar could see both us and the fighters, and the fighter director officer was trying to move us together. At this point Phillips—at O’Hare’s request—turned on our running lights, and the fighters, all lighted up themselves like Christmas trees, slid suddenly in, coming down across our tail from below and aft, O’Hare on our starboard side wing one or two hundred feet away somewhat below, Skon on the port, bright blue in the flare of their exhausts, six guns jutting out of their wings, quite scary. For one brief moment Butch O’Hare’s face was sharply illuminated by his canopy light, goggles up, yellow Mae West life jacket, khaki shirt, and helmet. He was seated aggressively forward, riding the plane hard, looking like the tough American ace, Medal of Honor recipient he was.

It was at that point that, attracted by our lights, one of the Bettys, as confused and blinded as we were, tried to join up on the American formation. Looking to my right, I saw a long black cigar shape climb up from below and aft of Skon and swing into formation above us on our starboard side, behind and slightly above O’Hare. Realizing his fatal mistake, he began firing. “Butch, this is Phil. There’s a Jap on your tail. Kernan, open fire.” The intercom went dead as I began shooting back at the Betty to our rear, which, as the tracers arced toward him, broke away across our group to disappear in the darkness behind Skon.

Rand in pain but staring out of the tunnel window, had a good view of the exchange of fire, but he missed O’Hare’s plane slipping under us, just forward of Skon, and away into the dark. I thought I saw O’Hare reappear off to port, for the briefest glimpse, and then he was gone. Something whitish-gray appeared above the water, his parachute or the splash of the plane going in. Skon slid away instantly to follow O’Hare, and then returned to join up on us again when he could not find him.

Phillips took us down to drag the surface for another long half-hour before giving up and making our way at about 2100 back to the Enterprise. Skon landed first without any trouble. But for us the evening was by no means over. We still had to make a landing on an unlighted carrier at night.

If it had been done before, it was certainly not standard procedure, and Phillips, despite having thousands of hours as an instrument instructor, had never done it, even in practice. We homed in on the white wake that marked the ship in the water, but there was no light anywhere on deck except the fluorescent wands of the landing signal officer standing on the end of the flight deck.

The Enterprise captain, Matt Gardner, must have known we would never make it back with the cumbersome plane in the dark, the pilot tensed to the snapping point, so he courageously turned on the shaded lights that marked out the flight deck for the crucial moment. They could only be seen from low and aft by a plane approaching for a landing, so they didn’t reveal the ship very much for very long to a submarine or the Bettys still flying about. This time it worked. We dropped heavily onto the deck.

My first encounter with media arrogance came while I was still standing at the urinal. “What happened?” a reporter asked. “Where were they? How many? Where is O’Hare? How many did you shoot down?”

The tone was hoarsely aggressive, and I felt the night flight was a complicated and deeply personal thing. I certainly didn’t feel like talking about it to anyone as abrasive and unpleasant as this man. He bored right in though, and began to try to construct the scandal he wanted. “How far away from O’Hare were you when he was hit? Were you shooting too?” And then, there it was: “Did you hit him?” I walked away shouting. “Get the hell away from me.”

He went off muttering about reporting me to the officers, but I suppose the public relations officer got hold of him and in the end he wrote a number of stories for magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, describing O’Hare going down amid a blaze of enemy gunfire while saving the entire fleet, with bouquets to everyone else involved, including me.

A few weeks later, The New York Times ran a story on the pilot that President Roosevelt termed “one of the greatest combat fliers of all time.” Our navigator, Lt. Rand, was quoted as saying, “I saw the fourth plane’s guns blinking red and he was shooting at Butch while our gunner, Kernan, was shooting at the Jap. I overhead Kernan tell Commander Phillips that he was opening fire and Phil in turn told Butch, ‘Butch, there’s a Jap plane coming into your tail.’”

“Then Butch’s lights went off. I looked again and he was gone.”

Copyright © The Naval Institute Press. Reprinted by permission.