A new Greensboro museum celebrates the courage of four young black men 50 years ago.

-

Spring 2010

Volume60Issue1

Winter weather canceled the sold-out gala banquet to celebrate the opening of the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina, on Saturday, January 30. But come Monday morning, glad throngs braved the cold to commemorate the day, 50 years earlier, when the civil disobedience of four young men in a luncheonette snowballed a change for America.

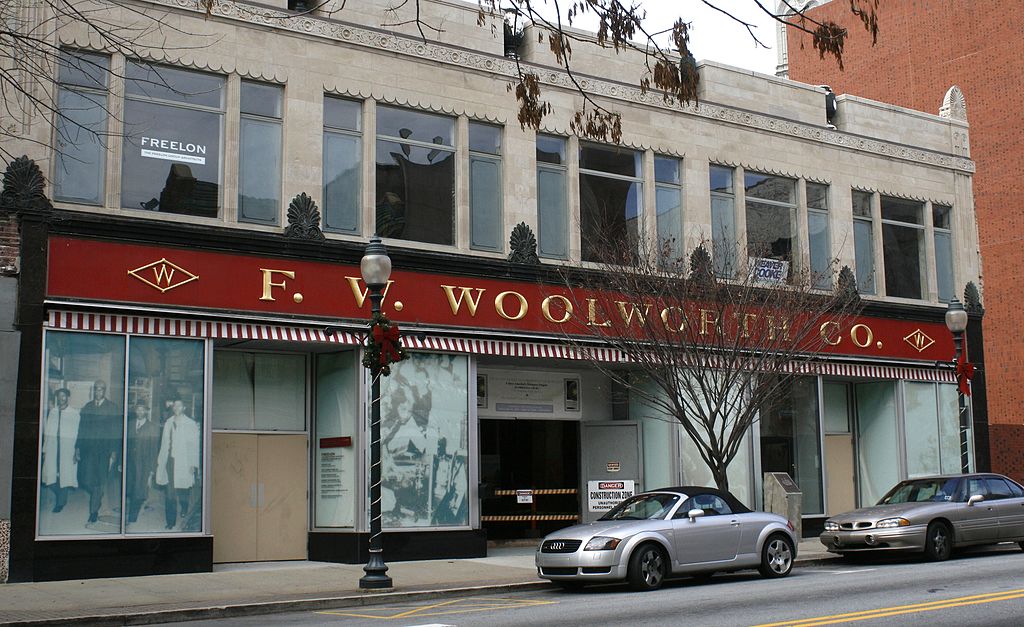

They were the “Greensboro four”—Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Jibreel Khazan (then Ezell Blair Jr.), and the late David Richmond—four freshmen at the local state college, who sat at the whites-only counter at the F. W. Woolworth five-and-dime store, ordered coffee and doughnuts, and held the first sit-in protest that launched a movement felt throughout the nation.

A film in the new museum reenacts the dorm room conversation that McNeil had with his classmates after Christmas five decades ago. He described his anger at not being able to buy a meal in the depots he passed through on the bus from New York City back to school after winter break. Throughout the South (and parts of the North), local custom then maintained separate facilities for “Whites” and “Coloreds”—separate rest rooms, separate water fountains, separate restaurants (or none at all for African Americans). The young men made a plan to do something about it.

That Monday—February 1, 1960—they walked into Woolworth’s an hour before closing and bought a few things. Then they sat down at the lunch counter and ordered drinks and snacks. A clerk refused to serve them because only whites could sit at the counter (blacks had to eat standing up or take their food outside). The manager alerted police to possible trouble but didn’t try to evict the orderly demonstrators. His superiors told him to ride things out; the problem would blow over.

The Greensboro Four returned the next day and every day that week, each time joined by a growing number of other students; some followed suit at the nearby Kress five-and-dime. Within a week, a thousand peaceful demonstrators and counterprotestors were facing off.

Although some white citizens grumbled, and rumors buzzed of Ku Klux Klan retaliation, civility prevailed. Greensboro’s city officials, police, and business leaders—including the Woolworth and Kress managers—chose to break the spirals of confrontation and violence that were disrupting life in other southern cities and lifted their whites-only policy by the end of July. Sit-ins soon became a cornerstone of the civil rights movement, spreading to 55 cities in 13 states.

As Senator Kay Hagan recalled at the new museum’s ribbon-cutting ceremony, “by the end of the week, hundreds from surrounding colleges and high schools—black and white, male and female, young and old—joined these four brave men to change history.” The national civil rights movement found its voice among the young: the sit-ins led to the Freedom Rides, mass protests, the Selma March, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on the National Mall, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which shattered the state laws that had barred African Americans’ access to political power since Reconstruction. (As President Johnson predicted, his civil rights policies also brought an end to the ‘Solid South” as a Democratic Party stronghold.)

As the decades passed, more and more young Americans of every color have grown up with limited understanding of historical racism and less knowledge of the civil rights movement. This prompted some Greensboro leaders to envision a museum that would commemorate the roller-coaster events that led to desegregation and that would teach lessons of the historical experience. Its first concrete goal was to renovate as its headquarters Greensboro’s art deco landmark, the Woolworth Building.

With 30,000 square feet of space, the museum focuses on the long, L-shaped Formica lunch counter, its pedestal stools boasting newly re-covered aqua and orange seats. It also features relics of the southern past: the shattered window from a church destroyed by a bomb that took the lives of young girls attending Sunday school; a Ku Klux Klansman’s robe; a two-sided Coca-Cola machine, which served whites and blacks separately; and a reconstructed archway reading “Colored Entrance,” which once led into the Greesnboro train station.

The museum’s Hall of Shame (open to children under 12 only with their parents) features grisly images of racial violence: lynchings and burned bodies; police dogs attacking protesters; the tortured face of 14-year-old Emmett Till in his open-casket funeral. Visitors hear the whoosh of fire hoses, and tree branches groaning with the weight of hanged bodies. In the museum’s Hall of Courage, vistors can take a simulated walk through Greensboro in the 1960s, the same one taken by the four brave freshmen on their way to Woolworth’s.

The museum also has a study center that will offer research facilities and encourage studies into the United States’ checkered history of segregation, integration, and civil rights. Its first order of business, says newly appointed curator and program director Bamidele Demerson, will be “to mine our own backyard—and the gems we have right here—in order to relate to national and international narratives and [teach] lessons in civil justice, civil rights, and human rights in general.”