Jan Scruggs fought on multiple fronts to build the Vietnam Memorial, which was once derided as a “black gash” and “Orwellian glop.” His work inspired a nation and helped bring Americans together.

-

June 2021

Volume66Issue4

Editor’s Note: James Reston, Jr. is a Vietnam-era veteran and author of seventeen books including A Rift in the Earth: Art, Memory, and the Fight for a Vietnam War Memorial about the founding of the Wall. His latest book is a 9/11 novel, The Nineteenth Hijacker, published in February.

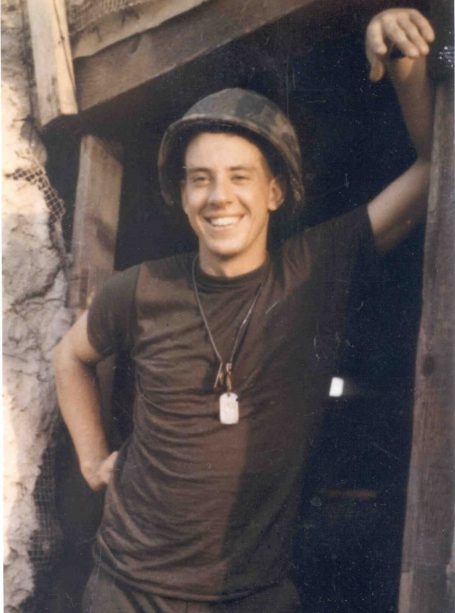

Torment was acute for many veterans in the years after the Vietnam War ended. More than 2.1 million men and women deployed over the course of the conflict, and returning soldiers were often scorned and humiliated as purveyors of death and torture, and dupes of a discredited policy. College friends looked on veterans’ service with mystification and disapproval, while they moved forward with careers or cared for trick knees.

How should a country heal after such a divisive war? What could be done to bring the rage and recrimination to an end? How long would the reconciliation take—if indeed the healing could ever happen?

Please sign our petition to ask President Biden to award the Presidential Medal to Jan Scruggs for his efforts to create the Vietnam Wall and heal our nation’s division.

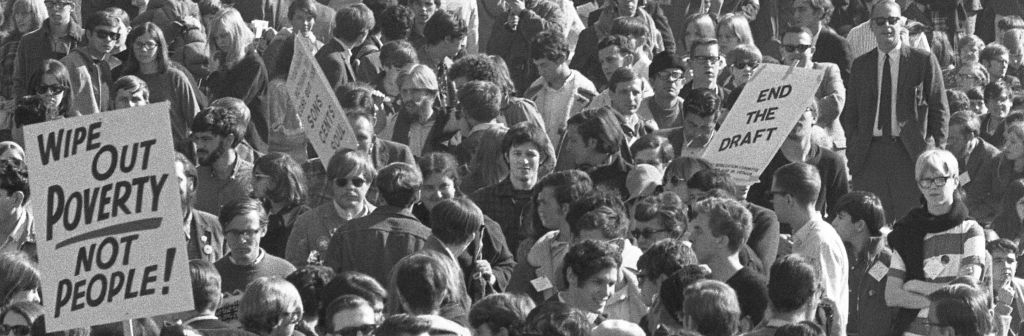

From 1978 to 1984, those profound questions were encapsulated in a brawl over how to commemorate the war, the first the United States had ever lost. It was an extraordinary struggle between groups with different attitudes toward what some called the 20th Century’s “lost cause,” and what constitutes honor and courage in times of national crisis. It was also a fight between people with different notions about public art.

At the time, the competition for an appropriate design to commemorate the sacrifice in Vietnam was the largest contest of its kind in the history of art with 1421 entries—a remarkable explosion of creativity. The surprising winner was a twenty-one-year-old Yale undergraduate named Maya Lin, whose concept of a simple, chevron-shaped black granite wall became instantly controversial. A cabal of well-connected, forceful veterans led the charge against it, denigrating the design as shameful and nihilistic, an insult to veterans and a paean to anti-war protesters. They did everything they could to scuttle the winning design and replace it with something more “heroic”… and they almost succeeded.

Long after the Vietnam conflict, the struggle remains intensely relevant for wars that America may fight in the future. The memorial on the National Mall is no longer just about veterans and their loss and sacrifice, no longer just about Vietnam, but about all wars and all service to country as well as moral opposition to governmental authority.

No one could have predicted that this simple space of contemplation has become one of the most popular sites in the nation’s capital, with over three million visitors a year. This simple V of black granite, even in its inscrutability, has risen to the universal.

Coming to terms with our defeat in Vietnam did not really begin until about five years after the last American soldier was lifted off the roof of the American Embassy in Saigon, when Jimmy Carter turned his attention to the anguish of Vietnam late in his presidency. On May 30, 1979, at a White House reception for veterans after the Memorial Day holiday, the president proclaimed that the nation was, at last, ready to change its heart and mind toward the Vietnam soldier and recognize his valor, sacrifice, and commitment.

Jan Scruggs, a shy, somewhat awkward twenty-nine-year-old veteran, deserved much of the credit for the shift. As a teenage member of the 199th Light Infantry Brigade, Scruggs had been badly wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade in a bloody battle northeast of Saigon in May 1969. In the time he spent in a hospital in Cam Ranh Bay recovering, he came to accept his injury without bitterness but as a predictable event of war. He had earned his “red badge of courage,” he would say.

Two months later Scruggs returned to duty. Then in January 1970 he saw twelve of his comrades pulverized when an ammunition truck exploded. “That’s what gave me PTSD,” he would say later. Over the course of his tour, he had seen half of his company killed or wounded.

Back home Scruggs graduated from American University in 1975 and went on to earn a master’s degree in psychology a year later, focusing on Vietnam veterans’ painful readjustment to civilian life and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). In May 1977, he penned an article for the Washington Post entitled “Forgotten Veterans of that ‘Peculiar War.’”

“Perhaps a national monument is in order to remind an ungrateful nation of what it has done to its sons,” Scruggs wrote. Fifteen months later he published a second bitter editorial about the “continued indifference” toward the Vietnam veteran. He had come to believe that something more than rhetoric was needed to honor soldiers like himself who had answered the country’s call, and his notion of a national memorial for Vietnam veterans was percolating.

In his writings, Scruggs was also channeling Carl Jung’s concept of “collective unconscious,” which he had encountered in his psychology classes. Jung argues that all humans share certain fundamental values, one of which is the deep appreciation for heroes and those who give their lives for others.

Scruggs imagined a memorial of names—having names on a memorial, he felt, would guarantee public and political support. Seeing the movie The Deer Hunter in early 1979 galvanized him, solidifying his idea of building a memorial to his fellow soldiers and realizing that, if it was to happen, he would have to lead the effort himself. As he remembered later, “I was thinking things over and got very depressed. I started getting flashbacks, it was just like I was in the Army again and I saw my buddies dead there, twelve guys, their brains and intestines all over the place, twelve guys in a pile where mortar rounds had come in.”

That spring in 1979, with $2800 of his own money and somewhat clueless about the immense hurdles he would face, Scruggs began to mobilize a campaign for a memorial that would honor the sacrifices of US servicemen in Vietnam. He imagined such a memorial in a prominent place on the National Mall, with a garden-like setting where visitors would come for rest and reflection. He hoped as well that there might be some sort of a realistic sculpture of the Vietnam soldier. In late April, Scruggs and friends formed a corporation called the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF). They held a press conference over Memorial Day weekend and boldly announced their intent to raise one million dollars to build the memorial.

But the effort got off to a rocky start. In June, Roger Mudd of CBS News reported that the group had raised exactly $144.50. Their efforts were spoofed on late night television.

Then there was the matter of the creation and execution of a memorial: who could design and build it? Scruggs and company selected Frederick Hart, a brilliant young artist who was then working on a sculpture for the entrance of the Washington National Cathedral. But the hasty selection of Hart was loudly opposed by a number of observers including the powerful art critic of the Washington Post, Wolf Von Eckardt. How could the VVMF blithely award such an important prize to their favorite sculptor, he fumed, no matter how nice and talented that artist might be? There had to be a national competition, Von Eckardt insisted, and he, by golly, would see to it that it happened.

The idea of design competitions for public art has a long and storied tradition in America. After George Washington’s death, a number of proposals surfaced for honoring the first president. One attempt was Horatio Greenough’s sculpture of Washington as a seated and half-naked Roman hero draped with a toga. His statue was received with universal scorn. Meanwhile, a commission of prominent Washingtonians was formed with Chief Justice John Marshall as chairman. The winning design by Robert Mills called for a five-hundred-foot Egyptian obelisk whose base was a pantheon of thirty columns and whose top featured Washington in a horse-drawn chariot.

A century later the long, troubled campaign to craft a memorial in Washington for Franklin Roosevelt met with disappointing results. Congress established an advisory committee in 1955 but the initial efforts for an FDR monument failed when the winning design was dubbed “instant Stonehenge” and discarded. “The notion of a modern monument is veritably a contradiction in terms,” lamented committee member Lewis Mumford. “If it is a monument, it is not modern, and if it is modern, it cannot be a monument.”

The failure of the FDR competition notwithstanding, Von Eckardt argued forcefully that something similar should be organized for this memorial. “To elicit powerful ideas, there must be a competition,” he wrote. “It would be corrupt for some more or less self-appointed committee to pick some favorite.”

The critic would have his way. In August, VVMF got its first political breakthrough when Senator Mack Mathias of Maryland contacted them and offered help, followed by Senator John Warner of Virginia. A bill to erect some sort of a Vietnam memorial began to make its way through Congress.

The open competition for a Vietnam War memorial was officially announced in November 1980, and a brochure and rules packet sent to every art and architecture school in the United States, as well as to architecture and landscape firms. The planning commenced for what was expected to be an enormous response. But how to administer the contest?

The VVMF board chose Paul Spreiregen, a noted architect in Washington who hosted a weekly design program on National Public Radio and had written a book on design competitions, to be its professional adviser. Eight distinguished architects and artists were tapped as jurors and submissions called for beginning in January 1981. The jury would examine the entries and choose the winner in late April.

The stated purpose of the memorial was “to recognize and honor those who served and died.” The submissions should be “reflective and contemplative” in character, as a catalyst for a process of healing and reconciliation. Through the memorial, it was hoped that “both supporters and opponents of the war may find a common ground for recognizing the sacrifice, heroism, and loyalty which were a part of the Vietnam experience.”

The most important rule was that entries be non-political. They were to express no opinion whatsoever about the rightness or wrongness of the Vietnam War itself.

The final footnote in the rules surely made many eyes roll. “Amateurs” were to have as much of a chance of winning as “professionals.” If an amateur should happen to win the contest but not have the skill or experience to execute their concept, the VVMF had the right to “supplement the skills of the winner with other necessary experts and consultants.”

In the summer of 1980, Andrus Burr, a junior architecture professor at Yale had spent his vacation touring cemeteries in Europe and studying war memorials. The following academic year Burr taught a seminar on funerary architecture and, after the competition was announced, changed his course plan and assigned his students to design a memorial for the contest.

On her Thanksgiving break, Maya Lin and three classmates traveled to Washington and walked the landscape of Constitution Gardens near the Lincoln Memorial. There, her vision was born. “It was a beautiful park,” she would recall later. “I didn’t want to destroy a living park. You use the landscape, you don’t fight with it.” Of the eventual submissions for Professor Burr’s class, Lin’s was the most arresting. It consisted of a horizontal V, with tapered ends.

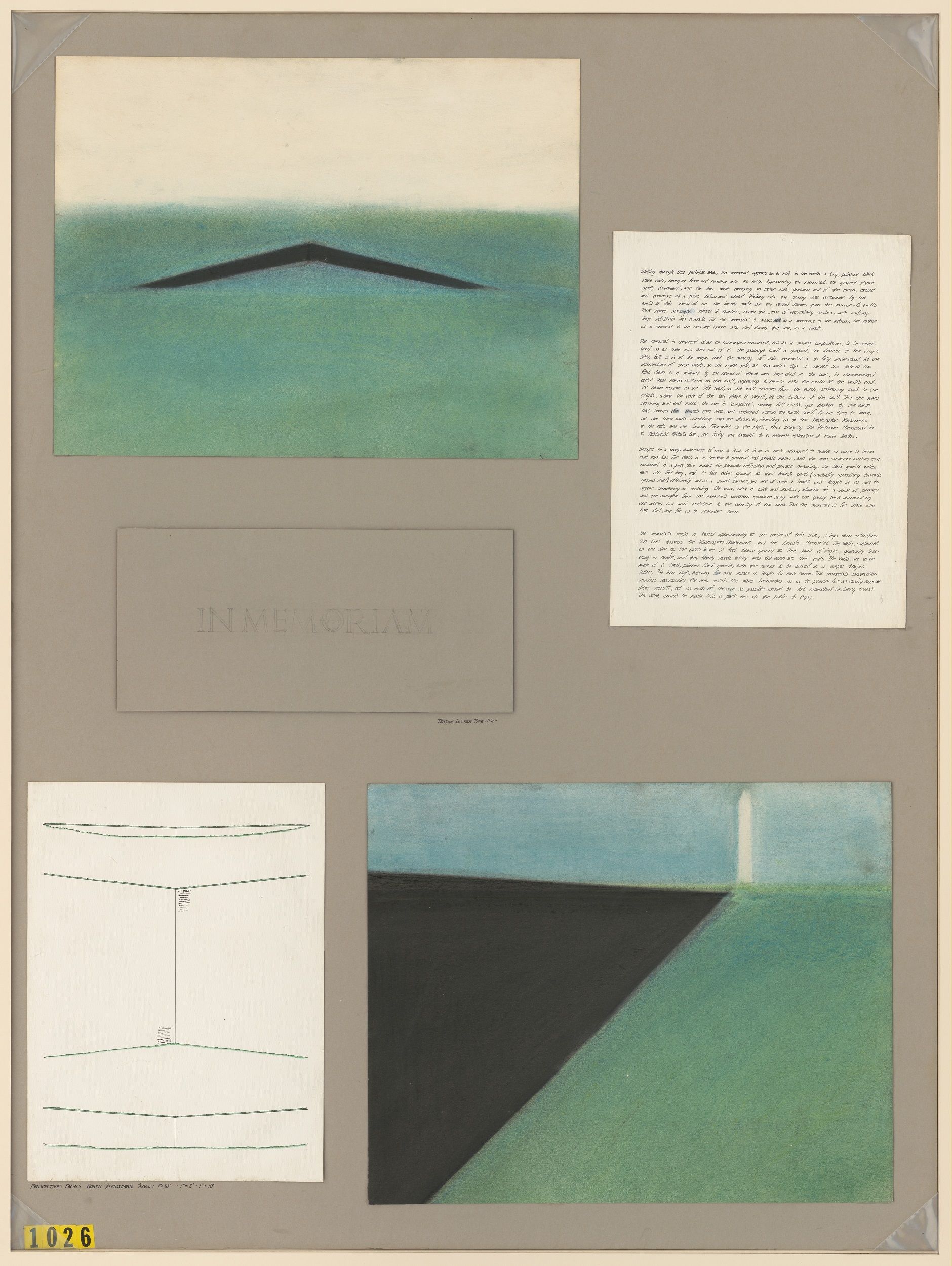

While the jurors were judging the entries, they came back time and again to the haunting submission identified simply as #1026. “He must really know what he’s doing,” a juror remarked, “to dare to do something so naïve.”

Submission #1026 was startling in its differences from all the other entries. Against an abundance of precise drawings by more sophisticated competitors, this entry was a triumph of simplicity.

At first glance, its two panels looked almost like the work of a high schooler by comparison, with the elemental black chevron like a floating mustache against a light blue pastel wash. In contrast to the fine geometric renderings of the other top contenders, this entry was ethereal and distinctly Asian in feel. Instead of the heroic labors of the others to fold softly into the existing landscape, #1026 proposed to cut deeply into the earth. Instead of comfortable words about heroism and service, valor and sacrifice, this submission had only a simple inscription: a large, gray rectangular panel with the words In Memoriam.

The handwritten words that described the vision of the artist imagined a “rift in the earth” in which a long polished black granite wall would emerge from and recede into the landscape. “Walking into this grassy site contained by the walls of the memorial we can barely make out the carved names upon the memorial’s walls.” The multitude of war dead would convey “a sense of overwhelming numbers.” And these names would be carved into the wall in the order in which they died in Vietnam, so that a stroll along the wall would become a chronicle of the Vietnam War from its first to its last American casualty. It would be up to each visitor “to come to terms with this loss.”

The entry did not impress every juror. Chairman Grady Clay found the display “sketchy” and “vague.” On the first pass, only three of the eight jurors thought well of it. But its strength and “deceptive simplicity,” in Clay’s words, grew on the jurors, and they kept returning to ponder its beautifully descriptive words. Hideo Sasaki, the influential landscape architect (who had been interned in the Poston, Arizona, camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II), was especially enthusiastic. In time, a consensus developed around it. They considered it to be far superior to all the rest.

On the morning of the fifth day, Clay gathered his notes along with the comments of the others as he prepared to write the jury’s verdict. The commemoration must have a sense of serenity, he wrote, and the wall of #1026 below ground would cut out traffic noise and thus achieve that desired effect. “Washington,” noted one juror, “is a city of white memorials, rising . . . this is a dark memorial, receding.”

“Many people will not comprehend this design,” one juror said of #1026.

“It will be a better memorial if it’s not entirely understood at first,” responded another.

But perhaps the most compelling juror observation was this: “Great art is like an unfilled vessel into which you can pour your own meaning... Each generation continues to do that... A great work of art is never complete and forever fresh.”

“The winning design is a great one,” Clay later wrote. “We believe it should be built as designed. It reflects the precise nature of the site designated by Congress. It is aligned beautifully with the Lincoln Memorial and Washington Monument . . . a unique horizontal design in a city full of vertical ‘statements.’ It uses natural forms of earth and minerals, without attempting to dominate the site. It invites contemplation and a feeling of reconciliation. The design, by creating a place of utter simplicity and serenity, is a work of art that will survive the test of time.”

When the label of #1026 was ripped off and the name revealed, the surprise winner was unknown to any of the jurors, an amateur and a young Asian-American woman by the name of Maya Lin. “Her design rises above [politics],” the juror Pietro Belluschi said. “It is very naïve . . . more what a child will do than what a sophisticated artist would present. It was above the banal. It has the sort of purity of an idea that shines.”

In the joint statement of all the jurors, there was this final praise: “This is very much a memorial of our own times, one that could not have been achieved in another time or place.”

But after Maya Lin’s design was chosen and announced, the public reaction was intense. Letters from outraged veterans poured into the Memorial Fund office. One claimed that Lin’s design had “the warmth and charm of an Abyssinian dagger.” “Nihilistic aesthetes” had chosen it. The design evoked the digging and hiding that a soldier had to do to survive in Vietnam. The proposal reflected the true situation of the Vietnam veteran: “bury the dead and ignore the needs of the living.”

An Army major called it “just a black wall that expresses nothing.” Predictably, the names of incendiary anti-war icons, Jane Fonda and Abbie Hoffman, were invoked as cheering for a design that made a mockery of the Vietnam dead. There was positive reaction too, but the negative feedback captured the attention of the organizers.

Maya Lin had specified polished black granite with no veining, and she had approved a sample from Sweden. Swedish black granite was the finest in the world, and there was no equivalent in the United States. But since Sweden (along with Canada) had been the prime destination for draft evaders, Swedish granite was out. The next best choice was granite from India. A few months later, when the memorial was debated in Congress, Rep. Larry McDonald of Georgia picked up on the Indian granite theme and labeled the wall “the black hole of Calcutta.”

A few days later, the conservative magazine National Review weighed in with a withering critique of Lin’s design. It objected to the black color, the listing of the names by date, and even to its V shape, which suggested the reviled peace symbol. The editors fumed: “If the current model has to be built, stick it off in some tidal flat, and let it memorialize Jane Fonda’s contribution to ensuring that our soldiers died in vain.” But the most memorable line was: “Our objection to this Orwellian glop does not issue from any philistine objection to new conceptions in art. It is based on the clear political message of this design.” The phrase “Orwellian glop” stuck.

This mixed reaction was even more critical in the arena of fundraising. Ross Perot, with a large financial investment in the competition and swelling with patriotic fervor, had waited anxiously to hear about the winning design. When he was told about the black wall, the Texan was decidedly negative, and when he saw the design model, he was apoplectic. Dismissing Scruggs’s plaudits for the design as a magnificent work of art, Perot remarked that it might be great for those who died, but it said nothing about the two million who served and survived.

Throughout the fall of 1981, other critics like ex-Marine-turned author Jim Webb led the blowback against Lin’s design. Webb likened the wall to a mass grave, arguing that it was only slightly better than no memorial at all. Webb also found a kindred soul in Vietnam veteran and West Point graduate Tom Carhart, who was stunned at the design, that “black gash of shame and sorrow,” and found it to be “intentionally insulting” to all who had served. Lin’s concept made him feel dishonored, and if it was built, it would be seen in the future as commemorating an “ugly, dirty experience of which we are all ashamed.” He would not apologize for his service to America, he said. The commission should reopen the competition and appoint a jury comprising only Vietnam veterans. He hoped for something white and graceful.

The final straw for Carhart was the winner herself. When he was first asked about what inscription should go on the wall, he suggested “designed by a gook.”

As counterpoint, Jan Scruggs, the father of the whole endeavor, pointed out that the detractors were a small group, well-connected perhaps, but scarcely representative of the veteran community at large. By way of contrast, he spoke of the American Legion’s support for the design. The Legion, the largest of all the service organizations, had contributed $1 million to the memorial, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, another major service group, had contributed $180,000. The Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) also supported Lin’s design. Thousands had seen the model of the memorial at recent veterans’ conventions, and they overwhelmingly accepted it as a beautiful tribute. Given the height of the wall at ten feet, veterans told Scruggs that the design made them feel ten feet tall.

As Christopher Knight, the art critic for the Los Angeles Times later wrote, the memorial was on its way to being recognized as “the greatest aesthetic achievement in an American public monument in the twentieth century.”

Nevertheless, Carhart’s indignation and overheated rhetoric could not be ignored, and it succeeded in planting a notion that would stick: the black gash of shame and sorrow. When their effort to cancel Lin’s statue failed, they did ultimately manage to impose an entirely different work of art on the winning design: a classical sculpture representing three soldiers in combat gear, fashioned by another remarkable artist, Frederick Hart.

By 1982, Hart was better known in the artworld than Lin by virtue of his masterwork, Ex Nihilo, at the Washington National Cathedral. His attention to detailed was unparalleled. And unlike Lin’s artistic remove, Hart had read deeply about the war. He had interviewed scores of veterans for his entry, and he had carefully nurtured his relationship with key players in the drama.

Hart would be the only sculptor considered. In his rendering, the three servicemen, fully equipped and armed GIs on patrol, stood close-knit, fully realistic, with their clothing accurate in every detail, and multiracial. Their poses suggest bravery, but also youth and vulnerability, and project the camaraderie and the wariness that defined the lot of the Vietnam soldier. Hart would tell his patrons later that he imagined his concept almost immediately and that the model almost sculpted itself.

As work was completed on the memorial, some of the opponents publicly accused the VVMF of financial impropriety, a charge repudiated by a major federal audit of Fund records. Opponents also tried unsuccessfully to get Congress to pass a law placing the statue in front of the walls. They may forever continue their war on Maya Lin’s design. Somehow their anger about the Vietnam War, rather than turning toward healing, seems transformed into permanent hatred.

In early 1983, a few months after the wall itself was dedicated on November 13, 1982, government commissions decided to put the statue and flag in an entrance plaza leading to the wall. The flag began flying from its 60-foot staff in mid-1983. At its base are emblems of the five services. The statue was installed on Veterans Day 1984. Lights, five permanent name-location guidebooks, and an expanded walkway have been added.

The Memorial now belongs to the U.S. government. Over 650,000 people paid for it with their private contributions. Over five million people visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial during its first two years. It is the second most visited memorial in the nation’s capital. On some days, over 20,000 people come. Late at night, at dawn, someone is always there. Most visitors touch the wall or hug each other. Many people come to see a special name. Every day someone leaves a flag, a flower, a snapshot, a memento, a poem, or a personal note. They linger and talk, and carry part of it away with them.

U.S. News & World Report called it in late 1983, one year after its dedication, “the most emotional ground in the nation’s capital.”

Thus, the eventual memorial was really two memorials in one, and the “art war” featured a clash of two entirely different concepts of art — one modernist, the other traditional — while raising questions about the inviolability of an artist’s work. At several moments in the struggle, it seemed as if the contentiousness was simply too great for any memorial to be built at all. And yet, once the art war ended and the dream of a memorial was realized, it was embraced with near universal acceptance and has become a place of reflection about not only the Vietnam War but all wars.

The process of reconciliation after such a divisive war can take years, for the bitterness on all sides of the issue is always severe. A process of coming to terms with what actually happened and why must precede a healing, a forgiving, and a forgetting.

“In dozens of memoirs I have read, veterans cite visits to the Wall as turning points in their lives," says Henry Zeybel, a retired Air Force navigator who flew in Vietnam. “In a somewhat magical way, the sight of the Wall and the visitors surrounding it gives many veterans a clearer understanding of the war and their involvement in it.”

Just as the Vietnam War memorial in Washington has transcended the specifics of the war it memorializes and ascended to the level of the universal, so the issue of reconciliation and reconstruction after a divisive war has also become timeless. Through the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and beyond, the period of peace in a war’s aftermath will be, and should be, a time for reflection, and hopefully, for renewal.

To have a permanent physical space to ponder those issues, a space that is almost sacred in feel, defines the brilliance of the Maya Lin and Frederick Hart creations.