The ex-slave and investigative journalist spent a lifetime fighting against lynching and segregation — but also for voting rights for African-American women.

-

September 2020

Volume65Issue5

Editor's Note: Susan Ware is a historian, general editor of the American National Biography, and editor of the biographical dictionary, Notable American Women. Among her books is Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote (Harvard University Press), from which this essay is adapted.

In the first six months of 1913, Illinois was a hotbed of suffrage activism, and Ida Wells-Barnett wanted to make sure that African American women were part of the action.

Despite being a longtime member of the Illinois Women’s Suffrage Association, she had not previously been able to drum up much interest on the question within Chicago’s growing black community. But now that the Illinois legislature was considering the law to grant presidential and municipal suffrage to women, things were different. “When I saw that we were likely to have a restricted suffrage.” Wells Barnett recalled, “and the white women of the organization were working like beavers to bring it about, I made another effort to get our women interested.”

On January 30, 1913 she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first African American suffrage organization in Chicago. Two months later, at a march timed to protest President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, she challenged the racism of the white-led national movement head-on — and she prevailed.

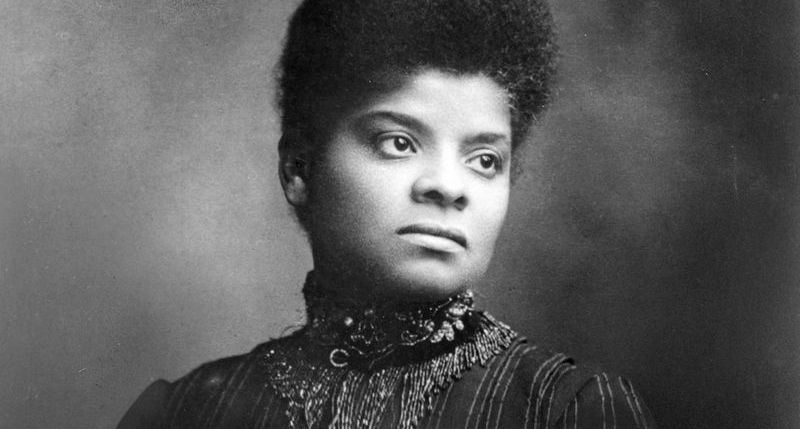

Ida Wells-Barnett was no stranger to controversy. Born a slave in Holly Springs, Mississippi during the upheavals of the Civil War, she spent the rest of her life fighting for full citizenship, both as an African American and a woman. After a yellow fever epidemic killed her parents and a younger sibling in 1878, she dropped out of school and became a teacher to support her family, even though she was only sixteen years old. Seeking broader opportunities, she relocated to Memphis, where she became a journalist.

Ida B. Wells’s first experience in challenging discrimination came in 1883, when she was forcibly evicted from the “ladies” car on a Chesapeake & Ohio train and forced to relocate to the much less commodious “colored” car. Indignant at her treatment, she sued the railroad company, claiming she was entitled to ride in the ladies’ car because she had purchased a full-fare ticket specifically designated for it. She won an initial settlement from the railroad company, but it was later overturned. Confirming the deteriorating climate for African American rights, the Supreme Court upheld the practice of Jim Crow segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

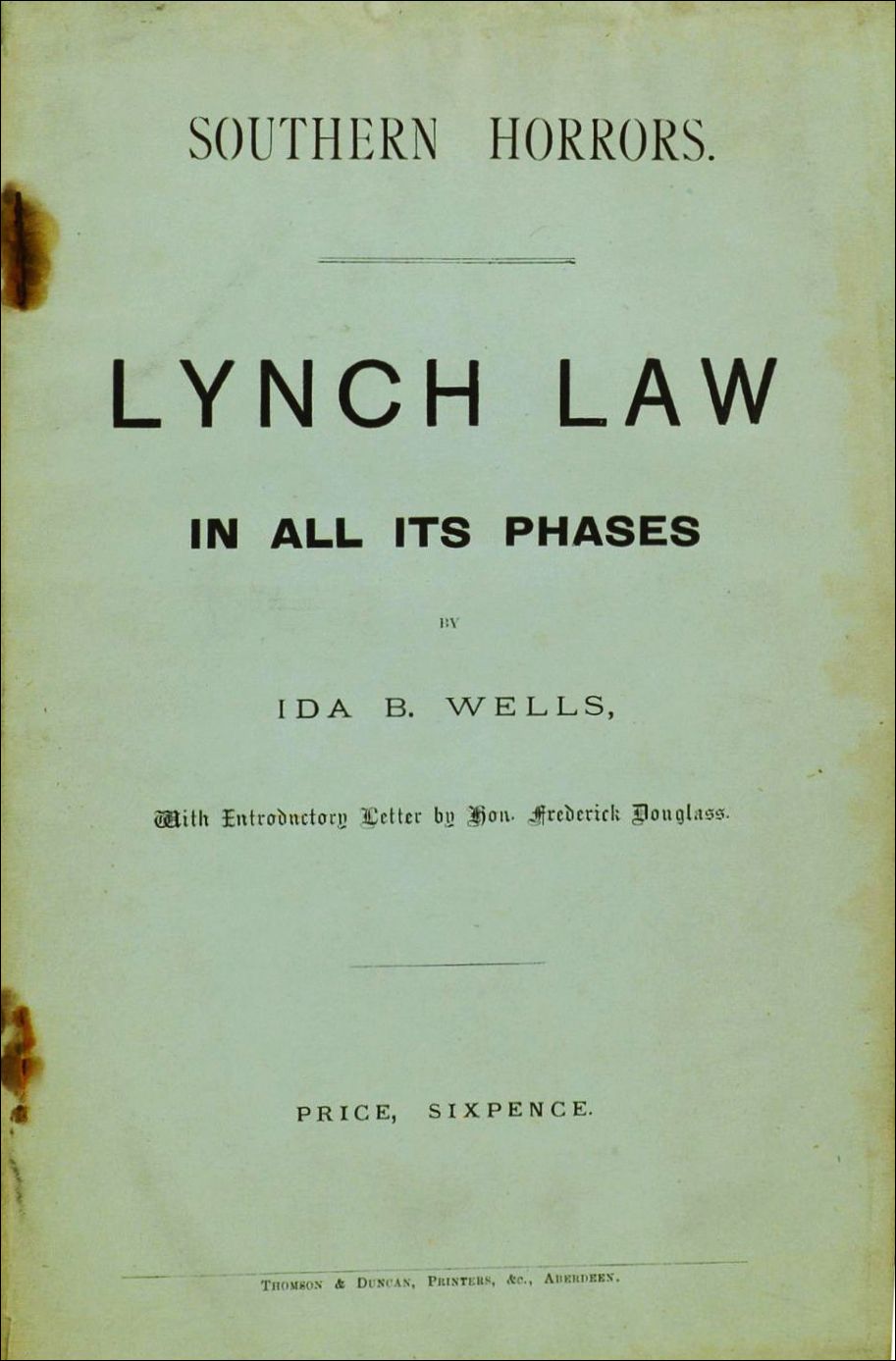

Ida B. Wells is best known for her anti-lynching activism. Her epiphany occurred in 1892 in Memphis, where she had become part owner of a newspaper called the Memphis Free Speech. When three black men were lynched by a white mob, Wells exposed the real reason for the racial violence in her pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases: successful black shopkeepers posed an economic threat to white businessmen.

She also challenged the claim that black men were lynched because they raped white women, pointing out that some white women voluntarily engaged in sexual relations with black men.

In retaliation for such inflammatory statements, the office of her newspaper was trashed, and she was basically run out of town. Several years later, she relocated to Chicago, where she married the lawyer Ferdinand Barnett and had four children. She lived in Chicago for the rest of her life.

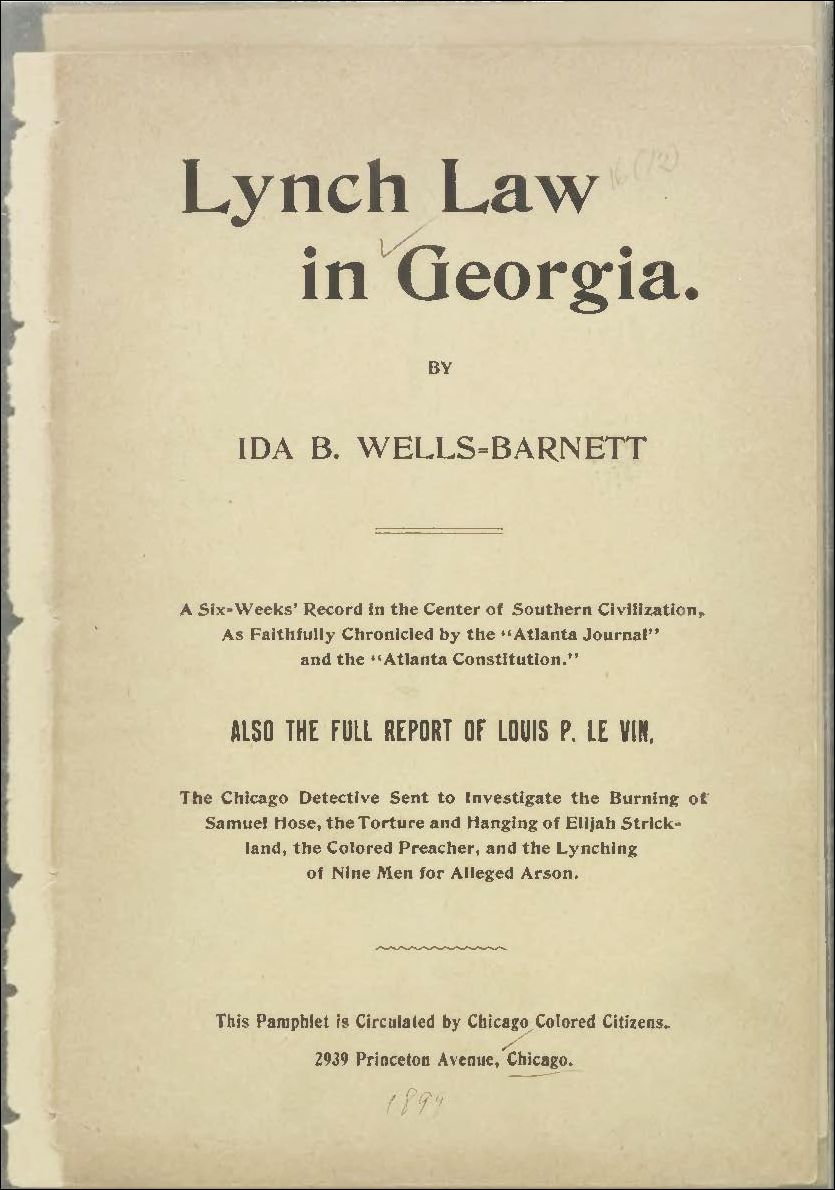

Anti-lynching was but one of the many crusades for justice that Ida Wells-Barnett (as she was now known) took on. In 1893, she publicly challenged the organizers of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago for excluding the contributions of African Americans. In 1894, she attacked the temperance leader Frances Willard for making racist statements about black men’s moral character and demanded, without success, that the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union make anti-lynching part of its broad reform agenda.

In 1910, she organized the Women’s Second Ward Republican Club on Chicago’s South Side, “to assist the men in getting better laws for the race and having representation in everything which tends to the uplift of the city and government.” She also founded a South Side settlement house called the Negro Fellowship League. Three years later, she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club.

Even though African Americans at the time were overwhelmingly associated with the Republican Party, the Alpha Suffrage Club was nonpartisan. Its primary goal was to educate African American women about the duties and responsibilities of citizenship and voting. As Wells-Barnett admitted, the club often started from scratch: “If the white women were backward in political matters, our own women were even more so.” The goal was to make African American women feel more comfortable in the realm of politics and then to “use the vote for the advantage of ourselves and our race.”

One of the Alpha Suffrage Club’s first tasks was to raise money to send its president to Washington, DC for the suffrage demonstration Alice Paul was planning on March 3, 1913, to coincide with Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Ida Wells-Barnett was one of more than sixty Illinois suffragists who made the trip — so many that the Chicago Tribune sent a reporter and photographer to cover the story.

Once the Illinois delegation arrived in the nation’s capital and began to practice their drill formation for the parade, Grace Wilbur Trout, the president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, informed the delegation that the leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association had advised them "to keep our delegation entirely white” because many women, especially those from southern states, would not march otherwise.

Instead, blacks were to be relegated to a separate section at the end of parade. “We should like to have Mrs. Barnett march with us,” Trout told the assembled Illinois suffragists, but “if the national association has decided it is unwise to include the colored women, I think we should abide by its decision.”

This stunning declaration caused a “murmur of excitement... around the room,” according to the reporter, “and those standing near the colored woman kept an embarrassed silence.” Virginia Brooks, a white woman who, along with Belle Squire, had affiliated with the Alpha Suffrage Club at its founding, quickly spoke up, pointing out that “we have come down here to march for equal rights,” and it would be undemocratic to exclude Wells-Barnett on the basis of race. “If women of other states lack moral courage, Brooks said, “we should show them that we are not afraid of public opinion. We should stand by our principles. If we do not the parade will be a farce.”

Then Ida Wells-Barnett spoke, her voice trembling with emotion and two tears rolling down her cheek, according to the sympathetic but somewhat patronizing Chicago Tribune account. “If the Illinois women do not take a stand now in this great democratic parade then the colored women are lost,” she argued forcefully.

When a white member of the delegation said in ignorance, “If I were a colored woman, I should be willing to march with the other women of my race,” it provoked a pointed response from Wells Barnett. “There is a difference... which you probably do not see. I shall not march with the colored women. Either I go with you or not at all. I am not taking this stand because I personally wish for recognition. I am doing it for the future benefit of my whole race.”

Grace Trout seemed swayed by these sentiments, and she agreed to take the matter up again with the national leaders, but to no avail. Although Trout personally disagreed, she said she would abide by their wishes. Wells-Barnett would have none of it. “When I was asked to come down here, I was asked to march with the other women of our state, and I intend to do so or not take part in the parade at all.”

When the Illinois delegation set out down Pennsylvania Avenue, four abreast and decked out in white dresses, “jaunty turbans,” and suffrage sashes, Ida Wells-Barnett was nowhere to be seen. Most of the delegates assumed she was either marching with the other black women or had decided to skip the parade entirely.

The Tribune reporter on the scene was a first-hand witness to what happened next: “Suddenly from the crowd on the sidewalk Mrs. Barnett walked calmly out to the delegation and assumed her place at the side of Mrs. Squire,” her white ally. No one questioned or challenged her, and she finished the parade as part of the Illinois delegation without incident. A photograph of Wells-Barnett, Squire, and Brooks ran on page five of the Chicago Tribune on March 5.

When Ida Wells-Barnett returned to Chicago after her momentous trip to Washington, she heard from Catherine Waugh McCullough, a leading white suffragist, who had read the accounts in the newspapers and wrote Wells-Barnett with unqualified support for her stand. “As I told Mrs. Squire and Miss Brooks,” wrote McCullough, “it only required that our women should be as firm in standing up for their principles as the Southern women are for their prejudices.” As a token of their budding friendship, Ida Wells-Barnett invited McCullough to the first annual dinner of the Alpha Suffrage Club held the following November.

Women like Wells-Barnett fervently believed that political engagement was a key tool for African American women to improve conditions for their communities and for their race. As a flier for an Alpha Suffrage Club meeting stated, “If the colored women do not take advantage of the franchise they may only blame themselves when they are left out of everything.” In many ways, black women could make the case that they needed the ballot even more than white women did, because of the dual discrimination they faced from racism and sexism. Sojourner Truth had made that same point decades earlier in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The vote took on an almost sacred role for African Americans in these years, precisely because of the systematic disenfranchisement of black men that had been occurring in the South since Reconstruction. If blacks could not vote in the South, then black voters in the North and West, both men and newly enfranchised women, might be able to use their votes to help their southern brethren. How? By voting the Republican ticket as a counterweight to Democratic Party control of the solid South, with the hope — albeit a distant one — of encouraging an activist federal government to take a larger role in protecting African Americans’ rights, as it had during Reconstruction’s brief heyday.

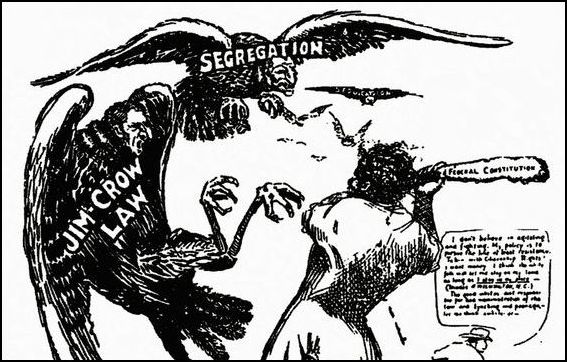

This sentiment was graphically represented in a May 1916 cartoon in The Crisis, the magazine of the recently founded National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Titled “Women to the Rescue!” it showed an African American woman defending her race against Jim Crow laws and segregation by wielding a bat representing the federal constitution.

The fortunes of African American suffrage and women’s suffrage were closely connected, even as they were on different trajectories. Geography mattered, as the ability to vote increasingly became determined by region more than gender or race: “The disfranchised, both men and women, resided in the South; the enfranchised, including women, lived outside that region.”

As African American men’s access to the ballot declined due to Jim Crow restrictions, women’s access expanded. The earliest suffrage victories occurred exclusively in the West, which resulted in the enfranchisement of women who were almost exclusively white. Only when more urban states like Illinois and later New York joined the suffrage bandwagon did black women benefit. But the deeply embedded racism of the suffrage movement meant that its leadership was unwilling and unable to embrace black women voters on an equal basis. Far too often, as the 1913 suffrage parade demonstrated, expediency prevailed, with southern support being deemed far more important than African American women’s aspirations for the vote.

Organized white women’s lack of interest in the voting rights of African Americans continued in the post suffrage era, when both the League of Women Voters and the National Woman’s Party consciously defined black voting rights as a matter of race, not gender, and thus not of primary concern to their political agendas. In many ways, the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, not the Nineteenth Amendment, was the culmination of black women’s long struggle for the vote.

Ida Wells-Barnett’s crusade for justice did not end with woman suffrage. She continued to play an active role in Republican Party politics in the 1920s, campaigning for Herbert Hoover in 1928 and providing strong support for a white candidate, Ruth Hanna McCormick, in two elections: her successful run in 1928 for congressman at-large from Illinois and her unsuccessful attempt in 1930 to be the first woman elected to the Senate.

While the main priority of the Alpha Suffrage Club remained political education and the election of the best “race men” to represent Chicago’s growing African American community, in the 1920s, Ida Wells-Barnett began to encourage women to run for political office themselves rather than just relying on men. Following her own advice, she ran for the state senate in Illinois in 1930, but finished a distant fourth. As she said with evident disappointment, “few women responded as I had hoped.”

While the main priority of the Alpha Suffrage Club remained political education and the election of the best “race men” to represent Chicago’s growing African American community, in the 1920s, Ida Wells-Barnett began to encourage women to run for political office themselves rather than just relying on men. Following her own advice, she ran for the state senate in Illinois in 1930, but finished a distant fourth. As she said with evident disappointment, “few women responded as I had hoped.”

At the time of her death the following year, Ida Wells-Barnett was working on an autobiography which ends, literally, in mid sentence. While the manuscript contains a full description of the Alpha Suffrage Club’s political activities in the 1910s, it failed to mention the 1913 suffrage parade. Perhaps she planned to include it in later revisions, or perhaps it didn’t loom that large in her memory.

But for generations since, Ida Wells-Barnett’s courageous defiance of suffrage leaders who told her, to use a metaphor from the civil rights movement, to move to the back of the bus has served as an iconic emblem of the deeply embedded racism and prejudice that marred what was supposed to be a movement for democracy and full citizenship.

Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.