The Union stood in danger of losing an entire army at Chattanooga. Then U. S. Grant arrived, and directed the most dramatic battle of the Civil War.

-

February 1969

Volume20Issue2 -

Summer 2025

Volume70Issue3

On October 17, 1863, aboard a railroad car in Indianapolis, Indiana, General Ulysses S. Grant met for the first time Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. The Lincoln government had suddenly come alive to the fact that one of its major forces, the Army of the Cumberland, faced imminent disaster in the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee, and fierce Stanton, “Old Man Mars,” had hurried west to straighten things out. He and the President had picked Grant to take charge. As commander of the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi, with jurisdiction over all Federal troops between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi River, Grant was ordered to get to Chattanooga without delay, restore the situation there, and take the military initiative away from the Confederates.

The war was momentarily stagnant. In Virginia, George Meade’s Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were too spent after Gettysburg to do much more than spar with each other. Along the Mississippi the edge gained by Grant’s brilliant conquest of Vicksburg was blunted by Washington’s preoccupation with military side shows and by Secretary Stanton’s rather myopic view of grand strategy. Before long Grant’s troops were scattered all over the map, garrisoning captured territory and becoming embroiled in fruitless forays west of the Mississippi.

So the focus shifted to Tennessee, and for a time the Federal situation there looked bright indeed. In late June General William S. Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland began to push southward from Murfreesboro; then, smartly outmaneuvering Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, Rosecrans chased the Confederates into northern Georgia and occupied Chattanooga, “the gateway to the Deep South.” This was a solid enough achievement, but Rosecrans got the idea that Bragg was in hopeless straits, and he sent his army chasing headlong through the mountains south of Chattanooga to apply the crusher.

Rosecrans paid dearly for his impetuousness. Bragg picked up reinforcements, including a corps from Lee’s army in Virginia, and on September 19 and 20, along Chickamauga Creek in northern Georgia, he smashed the Army of the Cumberland and sent it reeling back into Chattanooga. The Confederates occupied the high ground overlooking the city, snipped off all of Rosecrans’ supply routes except one wholly inadequate road, and sat back to wait for the Yankees to surrender.

All of this struck Washington like a lightning bolt. The war was lagging east and west; if an entire army was lost at Chattanooga, the repercussions were hardly to be imagined. Two corps were rushed south from the Army of the Potomac, Grant was ordered to send four of William T. Sherman’s divisions east from Memphis, and Secretary Stanton boarded the train for Indianapolis and his meeting with General Grant.

On his record, Grant was the clearly logical choice to straighten out the tangle at Chattanooga. At Shiloh, at Forts Henry and Donclson, and especially in his campaign against Vicksburg, he had proved that he could outthink as well as outfight his opponents. Abraham Lincoln, with that special perceptiveness of his, had early seen the qualities of the man. After the bloody fight at Shiloh in April of 1862, when the frightful casualty lists and the old tales of drunkenness had cast a pall over Grant, the President said simply, “I can’t spare this man: he fights.”

Now Grant held the top command in the West, and with it the job of getting the war moving again. He wasted little time disposing of Rosecrans; George H. Thomas, the one Union general who had enhanced his reputation in the Chickamauga battle, took over the Army of the Cumberland. Wiring Thomas to “hold Chattanooga at all hazards” (Thomas’ reply, “I will hold the town till we starve,” was as ominous as it was defiant), Grant set out for the besieged city, arriving on October 23 via the single road still in Federal hands: the gruelling journey was itself a grim demonstration of the problems ahead of him.

On the morning of October 24 Charles A. Dana, a War Department special observer in Chattanooga, notified Secretary Stanton that “Grant arrived last night, wet, dirty and well.” He added that the General had just gone out with Thomas to examine what looked like a weak spot in the encircling Confederate lines. Grant had wasted no time; by ten o’clock that morning he was riding north of the Tennessee River to grapple with his most pressing command problem—the matter of finding some way to break the siege before the army became too weak to fight.

He had the right men with him on this ride: Thomas, who had already endorsed a plan to break the siege, and the chief engineer officer of the Army of the Cumberland, Brigadier General William Farrar Smith, who had devised the plan and was prepared to execute it. Smith was universally known as Baldy—not, as a friend said, because he was notably bald, but just because there were so many Smiths in the army that each one needed a distinguishing nickname—and he had had his ups and downs; he had commanded a corps in the Army of the Potomac, ranking as major general, had lost command and rank when he fell into disfavor after Fredericksburg, and now he might be on his way back up. He could be brilliant one month and torpid the next. Luckily he was in his brilliant phase just now, and today he wanted to explain geography to General Grant.

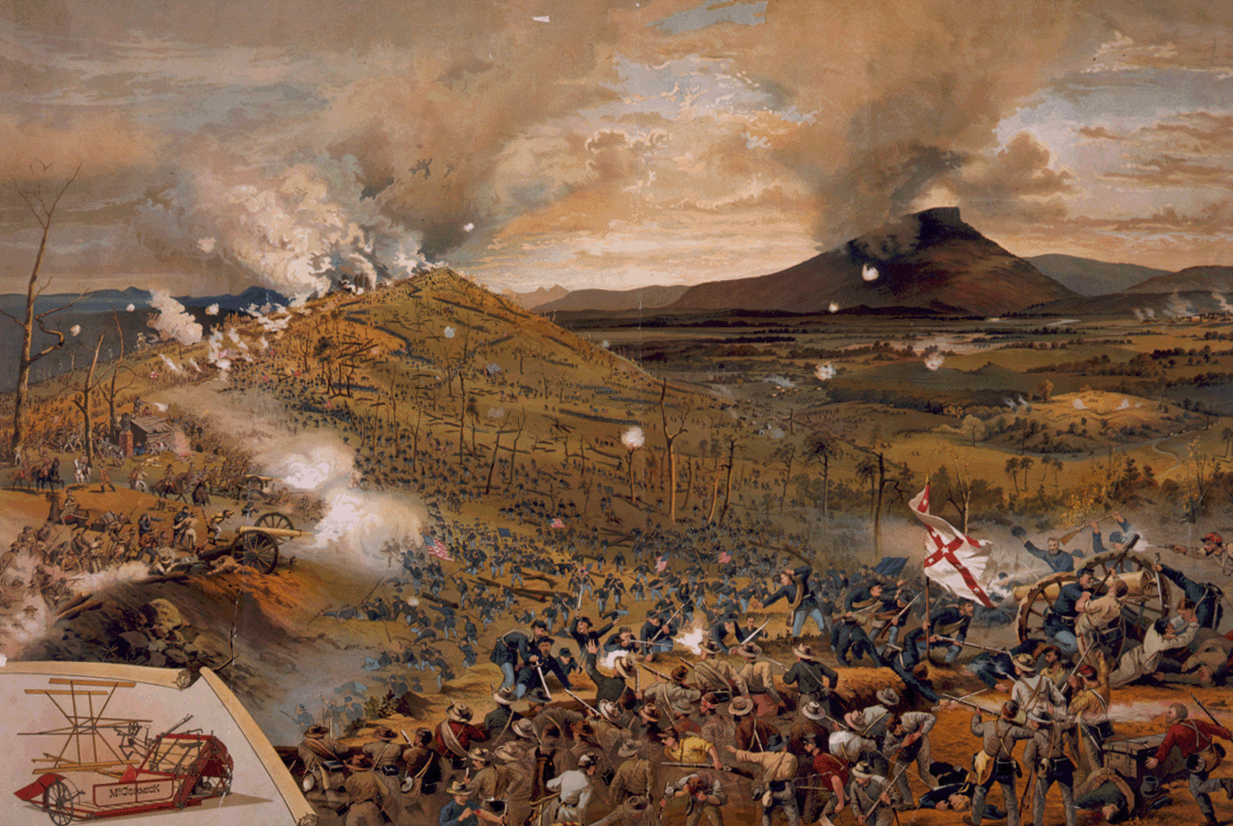

Geography was all-important. Chattanooga was locked in by the mountains. Looking south, the army in Chattanooga saw on its left the long diagonal of Missionary Ridge, five hundred feet high, touching the river east of town and then going south by west for seven miles. Every foot of this ridge was held by armed Confederates who had had a month to dig in, and there was no opening here no matter how long the commanding general might stare. When the army in Chattanooga looked to its right it saw something worse: the upper end of Lookout Mountain, a massive reef that came up one hundred miles out of Alabama, its axis pointing a little east of north, touching the river a few miles west of the city. Lookout Mountain rose 1,500 feet above city and river, its upper third a vertical palisade of sheer rock, with a long slope of farm and forest country sliding down from the base of the palisade to the river and the open country below. This slope, like Missionary Ridge, was heavily populated by Bragg’s soldiers, and between the mountain and the ridge the Federals were imprisoned. They could see their enemies, flickering campfires by night, emplaced guns and entrenched infantry by day, but the sight gave no comfort; from Fredericksburg through Gettysburg to Vicksburg the soldiers in this war had learned that to fight uphill against a properly prepared army was very bad going indeed.

Lookout Mountain mattered most, because it controlled the routes the Federals had to use to get in or out of Chattanooga.

In ordinary times there were four of these routes. There was the railroad, coming south of the river at Bridgeport and snaking through a pass in Raccoon Mountain to come around the end of Lookout into Chattanooga. There was a highway, good enough as American country roads went in those days, running near the railroad and accompanying it around the foot of the slope at Lookout’s northern end. There was also the river, usable by steamboats at most stages of the water, and the river skirted the northern tip of Lookout Mountain. Railroad, highway, and river were all blocked now, because the Confederate soldiers on the Lookout Mountain slope could lay fire on all three. For a fourth route there was a road that hugged the northern bank of the Tennessee, coming east from Bridgeport, and this one was blocked also because a good part of it lay within easy range of Confederate riflemen on the northern slope of Raccoon Mountain—a north-south ridge, much lower than Lookout, west of it, running more or less parallel to it, separated from it by the valley of Lookout Creek.

Four routes, then, all of them closed. The fifth was the one Grant had taken from Bridgeport, four times as long and ten times as difficult as the others. A small party could always get through by this road, but supply trains that had to use it could not give the Army of the Cumberland the volume of rations and forage it had to have, the chief trouble being that they could not carry the things the army needed plus the hay and grain their own teams needed to eat. The incredible number of ten thousand animals had perished on this road; the troops were on half rations, and it was perfectly clear that when winter came the road could hardly be used at all. Unless a better route could be opened soon the army was going to die, and so on this morning of October 24 Grant was out to see what Thomas and Baldy Smith had learned about geography and about Confederate troop dispositions.

They had learned a good deal, all of it encouraging.

Flowing west at Chattanooga, the Tennessee River abruptly turns south as soon as it is past the city, and it keeps on flowing south for two or three miles until it touches that northern toe of Lookout Mountain. Then it swings around in a sharp hairpin turn and goes back north again, enclosing a long finger of land known as Moccasin Point, the river’s hairpin turn bearing the name of Moccasin Bend, and makes its way around the northern end of Raccoon Mountain. All of these facts, of course, were visible to anyone who examined a map or climbed a hill and looked about him, but Thomas and Smith wanted Grant to reflect on certain subsidiary facts they had uncovered.

Across the base of Moccasin Point, hidden from Confederate view by woods and hills, there was an insignificant little road that left the river opposite Chattanooga and reached the river again at a nowhere of a place called Brown’s Ferry. The two generals led Grant there and showed him where opportunity beckoned.

On the opposite side of the river was the mouth of a valley that cut west across Raccoon Mountain, and after four or five miles this valley touched the river again at Kelley’s Ferry—which could easily be reached by road or by steamboat from Bridgeport. The opportunity, as Smith pointed out, was simply this: if the Federals unexpectedly put a pontoon bridge across the river at Brown’s Ferry and seized the road through the valley across Raccoon Mountain, they would have a direct route to Chattanooga from Bridgeport and the blockade would be ended.

To do this, of course, it would be necessary to drive the Confederates away from Raccoon Mountain, but this might be easy because Bragg’s army held this area weakly. Bragg’s left was commanded by James Longstreet, who had posted most of his army corps on the eastern and northern slopes of Lookout Mountain, detailing only one brigade to hold the valley of Lookout Creek and the northern part of Raccoon Mountain. At the break in the hills just opposite Brown’s Ferry there appeared to be no more than a company of infantry.

The Confederates here, in short, could be had, and Baldy Smith knew how to take them. He outlined his plan: stealthily, and by dead of night, float a brigade of troops in pontoon boats down the river from Chattanooga, gambling everything on the belief that they could slip around Moccasin Bend before the Confederates caught on, and have these men go ashore opposite Brown’s Ferry and seize the eastern end of the valley that cut across the mountain to Kelley’s Ferry. Meanwhile, march another brigade across Moccasin Point by the road the generals themselves had just used, and while the brigade that had floated downstream was making the Raccoon Mountain beachhead secure, let this brigade, using the flatboats that had brought the first brigade downstream, build a pontoon bridge at Brown’s Ferry, and as soon as it was done go over the river and lend a hand with the job of driving all hostile parties away from the Kelley’s Ferry road. All of this, said Smith, could be started in darkness and completed by a short time after daylight.

Over in the Bridgeport area there was General Joe Hooker, down from the Army of the Potomac, who had two army corps that were not now being used. Let him be ordered to march toward Chattanooga along the line of the railroad and its accompanying highway. This would bring him out at a place called Wauhatchie, on the eastern slope of Raccoon Mountain approximately four miles south of Brown’s Ferry. Once he did this the Confederates on Lookout Mountain could not interfere with the traffic between Bridgeport and Brown’s Ferry without fighting against odds under most unfavorable conditions.

Thus General Smith’s plan: simple, brilliant, promising a quick solution for the army’s worst single problem. General Thomas had already approved it, and preliminary activities were even now under way; all that these generals wanted was final approval from General Grant—that, and the assurance that the project had top priority and would get overriding directives in case of need. The approval and the assurance were quickly given, and Thomas and Smith hurried off to get the operation into high gear.

While the plan to break the siege received its finishing touches, Grant was dealing with a new crisis. A report from General in Chief Henry W. Halleck in Washington warned him that a corps from Lee’s army in Virginia was moving down into East Tennessee, posing a threat to both the Army of the Cumberland in Chattanooga and the Army of the Ohio, commanded by Ambrose Burnside, in the Knoxville area. It turned out later that the report was false, but Grant had to take it at face value and consider the damage a mobile force of 25,000 Confederates might accomplish in this part of the country. The only force available to him to counter this threat was Sherman’s, toiling slowly eastward from Memphis, repairing the Memphis & Charleston Railroad as it came. Grant ordered Sherman to forget railroad building and advance at full speed; Burnside was alerted to the danger. Grant was not to be distraded from the main issue, however: driving Bragg away from Chattanooga and opening the heart of the southland to a Federal invasion. And to that goal the Brown’s Ferry plan was vital.

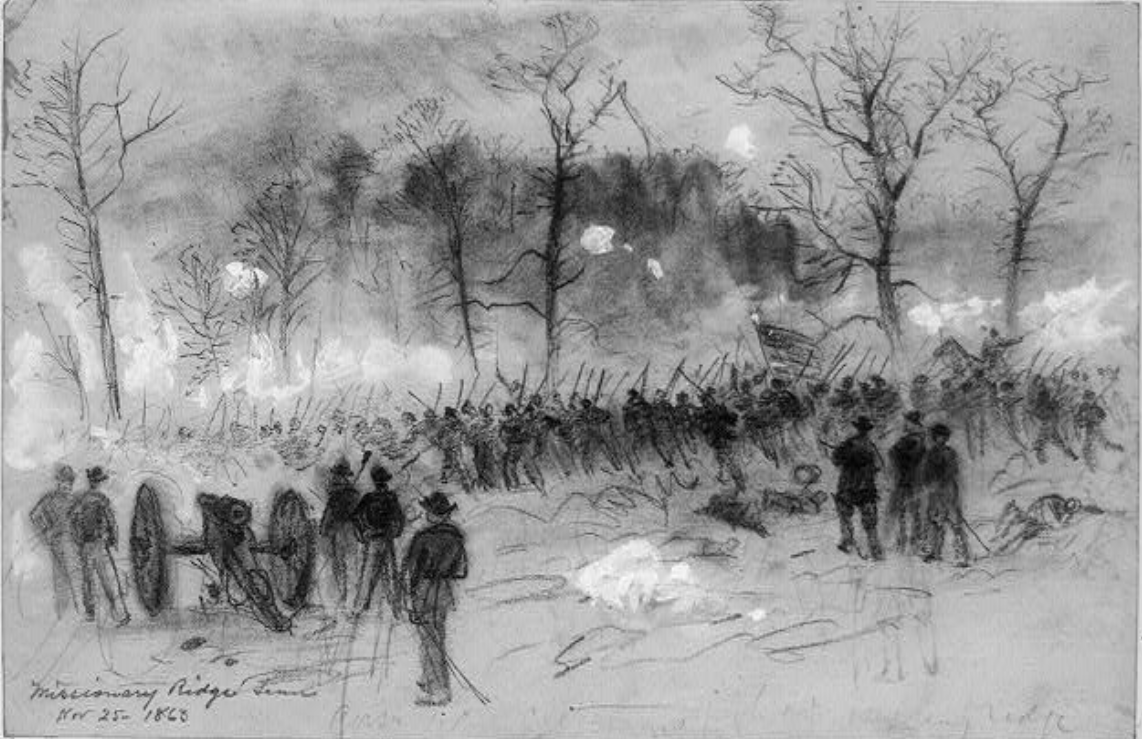

This operation went off like clockwork in the early hours of October 27. The water-borne brigade, under Brigadier General William B. Hazen, floated down the Tennessee, slipped undetected past the Confederate pickets in the darkness, and seized a bridgehead at the ferry; reinforced by a second brigade that crossed the river on the swiftly constructed pontoon bridge, the Federals cleared the road across Raccoon Mountain to Kelley’s Ferry. The next day Joe Hooker came up from Bridgeport in force to clinch the gains.

“General Thomas’ plan for securing the river and south side road hence to Bridgeport has proven eminently successful,” Grant telegraphed Halleck on the evening of October 28. “The question of supplies may now be regarded as settled. If the Rebels give us one week more time I think all danger of losing territory now held by us will have passed away, and preparations may commence for offensive operations.”

As far as the soldiers were concerned the new supply route was “the cracker line” because it brought boxes of the basic army ration, hardtack; and Grant got most of the credit for opening it simply because it happened a few days after his arrival. In his messages to the War Department, Grant was scrupulous to give the credit to Thomas and Smith, making it clear that the plan had been “set on foot before my arrival”; but he had automatically become a miracle worker when he captured Vicksburg and by now any good thing that happened in his jurisdiction was certain to be ascribed to him. Besides, a new atmosphere had unquestionably come in with him. General O. O. Howard, one of Hooker’s corps commanders, spoke of it, later that fall, in a letter to a friend in the Senate: “This department was completely ‘out of joint’ when we first arrived. A most complete & perfect want of system prevailed, from Louisville to Chattanooga. I can now feel the difference. … I cannot be too thankful for the policy that placed these three Depts. under Grant.”

This was all very well, and after a long period in which he never seemed to get much recognition for what he had done, Grant may have found it pleasant to get a little too much; and yet, even though opening this cracker line was one of the decisive events of the whole Chattanooga campaign—it meant, in effect, that Bragg had gone over from the offensive to the defensive, although Bragg did not yet realize it—Grant still had problems.

The unhappy truth was that the army’s whole transportation system—that is to say, the huge array of horses and mules that pulled wagons, guns, and ambulances, without which the army could not travel—had been almost ruined by the blockade, and the damage could not be set right immediately. Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General of the army, had come out to Tennessee to do what he could to improve matters, and on October 25 he sent a gloomy report back to the War Department: “The animals with this army will now nearly all need three months rest to become serviceable. They should be returned to Louisville for this purpose. Hard work, exposure, short grain and no long fodder have almost destroyed them.” It was quite true, as Grant pointed out to General Halleck, that steamboats now were running regularly between Kelley’s Ferry and Bridgeport, “thus nearly settling the subsistence and forage questions”; the army was not going to starve. To restore the army’s mobility would be another matter altogether.

It was at least beginning to be clear that the 25,000 men Lee was reported to be sending into East Tennessee were not coming. They never had been coming, because Lee simply did not have 25,000 men to spare. Yet even as this threat evaporated a new one appeared. On November 4, acting on a suggestion from President Davis, Bragg ordered Longstreet to take two divisions of infantry and some cavalry, leave the lines around Chattanooga, and move up the railroad toward Knoxville, with the injunction: “Your object should be to drive Burnside out of East Tennessee first, or better, to capture or destroy him.” Bragg knew that Sherman was on the way to join Grant, and he seems to have hoped that Longstreet could dispose of Burnside and then get back in time to help Bragg meet any attack Grant’s reinforced army might make. (At the very least, Longstreet’s move might compel Grant to detach troops to help Burnside.)

Longstreet, who had lost all confidence in Bragg, felt that the 12,000 infantry he would be taking were an utterly inadequate force, and he wrote bitterly that it was this army’s sad fate “to wait till all good opportunities had passed and then in desperation to seize upon the least favorable one.” With hindsight, it is easy to see that when he sent Longstreet away Bragg made a ruinous blunder; but in the first week in November, 1863, the move looked extremely ominous to the Federal authorities in Chattanooga and in Washington, partly because the size of Longstreet’s force was grossly overestimated. Grant found himself obliged to meet a new crisis.

He hoped that Hooker could clear the Confederates off the west side of Lookout Mountain and then move up Lookout Valley in such a way as to compel Bragg to recall Longstreet, but at best this was a thin hope. All Grant could promise was that a real attack would be made after Sherman arrived. To all intents and purposes the Army of the Cumberland had no transportation system whatever; it was hopelessly stalled. The infantry, to be sure, could walk, but Grant confessed that it could go only as far “as the men can carry rations to keep them and bring them back.” The artillery could not go at all. Using every expedient to provide teams, Thomas could move only one out of every six of the imposing array of cannon at his command. In midNovember the army was still paralyzed, and Grant told Halleck: “I have never felt such restlessness before as I have at the fixed and immovable condition of the Army of the Cumberland.”

Not in all the war did Grant live through a more tantalizing situation. By sending away Longstreet and two divisions of infantry, Bragg had prepared the way for his own defeat; Grant knew it, knew that a hard blow well delivered must drive the Confederate army back into Georgia—and found himself utterly unable to strike. From Moccasin Bend to the end of Missionary Ridge, the Confederate army was in plain sight, its campfires making a crescent against the sky night after night, its picket lines so close that Northern and Southern boys fraternized daily in a most unwarlike manner; but Grant and Thomas and all of their men might as well have been north of the Ohio River for anything they could do about it.

General Sherman finally reached Chattanooga on November 14, and on the day after this the generals crossed the Tennessee and rode a few miles upstream, eastward of Chattanooga, to examine the area where Bragg’s right flank could be assailed. Bragg had had Missionary Ridge all to himself for nearly two months, but up here where the northern tip of the ridge came down toward the river he did not seem to be very strong, and Grant’s plan for the battle hardened as the generals studied the scene with their field glasses.

If Sherman marched his force over from Bridgeport he could go north of the river at Brown’s Ferry and continue upstream opposite Chattanooga behind a range of hills that would shield him from Confederate view; and he could come out at water’s edge a short distance east of where the generals were now. Here Baldy Smith would have a fleet of pontoon boats, and in these Sherman’s men could cross the river and smite Bragg’s flank before Bragg realized what was afoot. To distract Bragg’s attention, Sherman could detach a brigade or so to move up Lookout Valley, over beyond the Confederates’ left, as if to make an assault on that flank. Sherman could also lend Thomas horses and mules so that Thomas could move his artillery and ammunition wagons, and Thomas could attack the lower part of Missionary Ridge while Sherman was attacking it near the river. If things were done properly, Bragg’s army should be roundly defeated.

The plan was highly flexible, so that whether it led to a big fight or an elaborate maneuver would depend largely on circumstances—on what Sherman found when he got past the northern end of Missionary Ridge, and on how Bragg responded to his appearance there. Similarly, Thomas was to mass his own men so that they could co-operate with Sherman or strike a blow of their own, as headquarters might direct; Hooker’s troops were to hold Lookout Valley, and perhaps they would be ordered to drive the Confederates off the mountain’s northern slope. On Thursday, November 19, Secretary S tan ton telegraphed to President Lincoln (who had gone to Gettysburg to make a speech) that Grant had things moving at Chattanooga and that “a battle or falling back of the enemy by Saturday, at furthest, is inevitable.”

Then it began to rain, and it kept on raining for two days, turning the roads to fathomless mud and reducing Sherman’s march from Bridgeport to a crawl. The heavy rains also caused a rise in the Tennessee River, the swollen waters carried much driftwood downstream, the driftwood battered at the pontoon bridge at Brown’s Ferry, and before Sherman had all his men across there the bridge was swept away. On each of three successive days Grant had to notify Thomas that the attack would have to be postponed. In the end, instead of being in position to open the battle on Saturday, Sherman could do no better than to get the head of his long column into position north of the Tennessee late on Monday, November 23.

This disturbed Thomas, who felt that with all of this delay Bragg was bound to discover what the Federals were going to do. On Sunday, accordingly, Thomas urged Grant to revert to the original plan and have Hooker attack Lookout Mountain—on the sound theory that Bragg could strengthen his right to meet Sherman only by weakening his left. Grant agreed, moved partly by a suspicion that Bragg might be preparing to retreat. On November 20 Bragg had sent a cryptic note to Grant under a flag of truce: “As there may still be some non-combatants in Chattanooga, I deem it proper to notify you that prudence would dictate their early withdrawal.” This was the kind of note a general sent across the lines when he was about to bombard and assault an occupied town, and Grant had no notion that Bragg planned to do anything of the kind; he showed the note to his visiting cousin-in-law, William Smith, grinned, and said that he had not answered it “but will when Sherman gets up.” Still, the note might be a ruse to cover a withdrawal; and two days later, when a Confederate deserter came into camp and said that Bragg’s army was beginning to retreat, Grant concluded that it was time to act. … The deserter was wrong, although he thought he was telling the truth; misguided to the end, Bragg had detached one more infantry division and sent it to East Tennessee to help Longstreet. After the war someone suggested to Grant that Bragg could have done this only in the belief that his position on Missionary Ridge was invulnerable. Grant thought a moment and then said drily: “Well, it was invulnerable.”

So orders were revised. On Monday, November 23, Thomas was told to drive in Bragg’s skirmish line, on the rolling ground in front of Missionary Ridge; if Bragg had really begun to leave, Grant said that he was “not willing that he should get his army off in good order,” and in any case a brisk demonstration would show whether he was leaving or holding his ground. At the same time Grant sent new orders to Hooker, over on the far side of Lookout. On the morning of November 24 Hooker was to take everybody he had and assault Lookout Mountain, as the original plan had contemplated. By this time Sherman would be ready to make his own attack, and Bragg would be assailed at both ends of his long line; and Thomas would be massed in front of his center, ready for anything.

So it fell to George Thomas, after all, to open (and, finally, to win) the Battle of Chattanooga. What he was supposed to do was pure routine: advance just enough men to make the opponent show his hand. What he actually did was move up everybody he had, in a massive advance of unlimited potentialities. Not for Thomas was the business of tapping the enemy’s lines lightly. If he hit at all, he hit with a sledge hammer; and on November 23 he put the better part of two army corps in line and sent them rolling forward in a movement that had a strange, unintentionally spectacular aspect—which somehow set the tone for the entire battle.

For Chattanooga, from first to last, was the most completely theatrical battle of the entire war. This seems odd, considering the fact that Grant and Thomas were two of the least flamboyant soldiers who ever wore the United States Army’s uniform, but that is how it was. The battle was almost unendurably dramatic, giving rise to innumerable legends, and it stirred Grant himself, so that a week later he wrote to Congressman Elihu Washburne: “The specticle was grand beyond anything that has been, or is likely to be, on this Contenent. It is the first battle field I have ever seen where a plan could be followed and from one place the whole field be within one view.” As usual, Grant was careless about his spelling; but the fearful pageantry of this battle got under his skin, just because he could see it all at once. Civil War battles mostly were like modern battles: that is, the ordinary soldier could see nothing whatever except what happened within a few dozen yards of him, and he never really knew what was going on anywhere outside of his immediate vicinity. At Chattanooga almost everybody could see almost everything. The soldier not only knew what was happening to him: he could see what his comrades were doing five miles away, he was a participant and a spectator at the same time, and in some indefinable way what he saw had a profound effect on what he did. This battle was a spectacular, and nobody knew quite what to make of it.

Thomas’ lines, in front of Chattanooga, were perhaps two miles away from the foot of Missionary Ridge. Between the ridge and the town lay open country, mostly a rolling plain, and halfway across there was a chain of low hills, of which the highest was called Orchard Knob. On Orchard Knob and the modest elevations that tailed away from it, Bragg had a skirmish line, and it was this skirmish line that Thomas proposed to dislodge. To do it he put three divisions in line of battle, with a fourth massed where it could go in and help if anybody needed help. The Federals spent half an hour ostentatiously dressing their ranks, and from the top of Missionary Ridge the Confederates looked down, saw it all, and concluded that the Yankees were going to hold a review. Then Thomas sent his men forward, and the flood tide swept up over Orchard Knob and the little ridges around it, and the mile-wide line of advance, its front all sparkling with the fire of the skirmishers, flooded the plain and the higher ground and drove Bragg’s outpost line back to the rifle pits at the foot of Missionary Ridge. Thomas’ men dug in on Orchard Knob and on both sides of it, and when sundown came the first day’s fight was over.

Considered strictly as a fight, it had been small. Thomas lost fewer than two hundred men, Confederate losses were no greater, and nothing very much had been done—except that the Federals knew Bragg was not retreating, Thomas had taken a position from which he could make a real fight whenever necessary, the Federal lines in Chattanooga were less cramped than they had been, and Bragg had been forced to reflect on the insecurity of his own battle line. A correspondent for the Richmond Dispatch, watching this affair from on top of the ridge, wrote that night that “General Grant has made an important move … likely to exert an important influence on military operations in this quarter,” and predicted that Bragg would be obliged to weaken his force on Lookout Mountain in order to strengthen his right.

The prediction was correct. That night Bragg took one of the two divisions on Lookout Mountain and moved it far around to the upper end of Missionary Ridge, to strengthen the position which seemed to be menaced by Thomas’ advance. That night, also, Sherman got three divisions in place north of the Tennessee, just across from the upper end of Missionary Ridge; and as far as anyone at Federal headquarters could see, Bragg could be hit hard on both flanks the next morning.

So much for November 23: a curtainraiser, setting the stage, setting also the tone, giving the defenders on Missionary Ridge a long look at an army that began to seem irresistible. Next morning came in with a cold drizzle, and from Orchard Knob anyone who looked to the north saw the Tennessee River full of crowded pontoon boats as Sherman’s men made their crossing. This operation took time, and by noon the people at headquarters were wondering why more of a fight was not developing there; and then, from far to the right, down on the western slope of Lookout Mountain, there came an immense crash of musketry and artillery fire, and no matter what Sherman was doing, Joe Hooker was going into action.

Taken in front and in flank, the Confederate line defending Lookout Mountain was compelled to give ground, and foot by foot the Federals cleared the western slope of the big mountain and swung around to attack the northern slope. Here the going became harder. The ground was steep, cluttered with boulders and cut up by irregular little gullies, there was a dense fog so that men fought blindly, and to maintain a coherent battle line while advancing along the side of a steep hill was difficult. At the foot of the northern end of the high palisade there was a little open plateau where the Confederates had an entrenched position, and in this place they put up a stout resistance. The noise of the firing seemed to be intensified as the sound waves echoed off the vertical rock walls that towered over this strange battlefield, and to Thomas’ men down in the great open place between Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge it seemed that a titanic struggle must be taking place. Not being in action themselves, these men watched intently from afar. They could see nothing but battle smoke drifting up from a mountainside that was still hidden by the fog.

Then, unexpectedly, came one of the improbable, dramatic moments of this Battle of Chattanooga. The Confederate defense line on Lookout was badly outnumbered, and by midafternoon it began to give way—and at that moment the fog suddenly drifted away, the sun came out, and the whole scene was visible. The men of the Army of the Cumberland could see everything, the Confederates were in full retreat, and around the curving slope came rank after rank of Hooker’s men, flags flying, rifle barrels shining in the sunlight, victory achieved in plain view of everybody—and Thomas’ soldiers jumped up and yelled and tossed their caps in the air, regimental bands spontaneously began to play from one end of the line to the other, the artillery fired wild salutes aimed haphazardly at Missionary Ridge, and the noise of the fighting was drowned in the noise of a general jubilee. Then, just as if a stage manager knew when to close a brilliant scene, the clouds hid the sun again, the drifting fog came back, the Lookout Mountain battle lines vanished from sight; and Grant, who had been over on the left of Thomas’ line, came riding back toward the center, as leisurely and unemotional as a farmer going out to inspect his acres. He dismounted, got down on one knee, rested his order book on the other knee, and scribbled messages to make sure Hooker got any reinforcements he might need. Then darkness came, and as the mist vanished once more, Hooker’s campfires could be seen, snaking up and down the long slope, with snapping spits of light out in front where pickets and skirmishers kept up an intermittent fire. Grant’s staff stayed up late to enjoy the sight, and Grant remarked that all of the Confederate troops would be gone from Lookout by morning.

Hooker, who had his own eye for drama, sent patrols up a winding road on the eastern side of the mountain before daylight, and at dawn a party from the 8th Kentucky reached the topmost, outward-jutting crag of rock on the summit. There the men waited, and when the sun came out they unfurled the biggest flag they had and waved it in the morning air, and everybody on the plain saw it and let off a new outburst of cheers and band music. An emotional officer on the plain confessed that “the pealing of all the bands was as if all the harps of Heaven were filling the dome with triumphant music,” and after this promising beginning he added that “it is useless to attempt a description of such a scene as that,” leaving literature much the poorer. And thus a great legend was born, and the fight on Lookout Mountain became “the battle above the clouds,” thenceforward and forever, with its impossible picture of heroic soldiers scaling sheer precipices under heavy fire. The legend became so great that after the war it irritated General Grant, who called it “one of the romances of the war” and said that there had really been nothing worthy of being called a battle on this mountain: “It is all poetry.” This was going a little too far, because Hooker’s troops had done a certain amount of fighting along with all of their climbing and scrambling, but the romance had taken enduring form and there was no way to diminish it.

Meanwhile there was Sherman, who was supposed to have the principal part in the battle and who on November 24 contributed nothing to legend but something to misunderstanding. During the afternoon he began to move eastward from the river and sent a battle line up what he supposed was the northern end of Missionary Ridge. The ground was steep but there was strangely little opposition—nothing but a little rifle fire from scattered Confederate patrols—and Sherman’s men got up onto the high ground without trouble. Ahead of them, less than a mile away, was a bulging eminence beneath which the railroad that ran eastward from Chattanooga ducked through a tunnel, and this height, known as Tunnel Hill, looked like the key to Bragg’s whole position; headquarters’ advance planning had written Tunnel Hill down as the army’s principal objective in the entire battle. Sherman believed that he was in an excellent position to make an assault, and that evening he notified Grant that he had carried Missionary Ridge as far as the tunnel. Grant ordered him to make the attack in the morning, saying that Thomas would either strike Bragg’s center or come up in Slierman’s support as circumstances might make advisable. It was an excellent plan, and it probably would have worked, except that Sherman was not where he thought he was.

Grant, Thomas, Sherman, and Baldy Smith had gone over their maps carefully and had studied the ground as well as they could on that excursion north of the Tennessee River, and in some inexplicable way they had made a profound mistake. The high ground that Sherman occupied on the afternoon of November 24 was not the northern end of Missionary Ridge at all; it was simply a detached hill, completely separated from Missionary Ridge by a deep valley with steep sides. Far from having reached a good place from which to assault Tunnel Hill, Sherman had reached the worst spot imaginable. In effect, he would have to fight a battle just to get to the place from which he could mount his main attack. Bragg had finally seen what was coming, and had sent a division led by his best combat soldier, General Patrick Cleburne, over to hold Tunnel Hill and the knobby ground north and east of it.

The truth began to be visible at Federal headquarters around 7 A.M. , when Sherman’s attack failed to develop. His men found that getting down from their own ground into that unanticipated valley was bad enough, because there were Confederates on the far side shooting at them, but going up the opposite side was much worse, because Cleburne’s artillery and infantry could send a vicious fire slicing all along this slope. One Confederate remembered that when a Union advance was driven back “it looked like a lot of the boys had been sliding down the hillside, for when a line of the enemy would be repulsed they would start down hill and soon the whole line would be rolling down like a ball, it was so steep a hillside just there.”

As soon as he learned that Sherman was going to be late, Grant postponed Thomas’ attack and sent word to Hooker to march south along the eastern foot of Lookout Mountain. After four or five miles Hooker could turn left and hit the southern end of Missionary Ridge at Rossville Gap, which would put him on Bragg’s left flank in position to drive northward along the ridge, crumpling the Confederate line as he came. Then, even if Sherman’s assault remained hung up, Thomas could strike his own blow at the center.

Thomas’ part had always been thought of as supplementary, simply because to storm the main line on Missionary Ridge seemed impossible unless most of the Confederate army was kept busy elsewhere. At the foot of the ridge there were rifle pits, halfway up there were a few uncompleted works, and all the crest was lined with infantry and artillery. An attacking column would be under artillery fire for nearly a mile before it even reached the rifle pits, and the slope beyond the pits was so steep that one of Thomas’ generals told his officers to leave their horses behind. During the night a Confederate staff officer rode the length of the crest and noticed that the line was pretty thin; there was only one rank, and the men were spaced farther apart than was usually considered advisable. He told General William J. Hardee, one of Bragg’s corps commanders, and Hardee agreed with him—the line was thin, but the natural strength of the position was so great that the Yankees probably would not attack at all.

They would not … except that Chattanooga was a battle in which nothing was quite as it seemed. Maybe the field was under a spell. There had been dazzling moonlight, night after night, all week; then, last night, there was a total eclipse, the moon went dark and the earth went shadowy-gray, and the thousands of campfires on the sides and crest of the ridge and on the broad plain below glowed like dying embers on a lunar landscape. Many of the soldiers were wakeful, and they agreed that this was a powerful omen meaning bad luck for somebody. Nobody was quite sure which side was going to get the bad luck.

At the very least, plans would go wrong. The plan that involved Hooker gave way almost at once. Hooker had to cross Chattanooga Creek, which was more of an obstacle than the word “creek” implied. The bridge he was to use had been destroyed, and for several hours he had to wait while a new bridge was built, and while he waited Thomas waited and Sherman got nowhere, and Grant’s whole battle plan was stalled. And at last—two o’clock, perhaps, or near it—Grant concluded that Thomas must attack no matter what was happening elsewhere.

So Thomas got new orders—to “carry the rifle pits at the foot of Missionary Ridge, and when carried to reform his lines on the rifle pits with a view to carrying the ridge.”

Grant was giving himself two chances, based on the belief that the Confederates were not strong enough to repulse two offensives at the same time, and it did not matter which chance worked. Grant believed that Bragg had weakened his center to defend his right, and if this was true Thomas ought to be able to break through. On the other hand, when Thomas attacked, Bragg might recall troops from his right, and if he did this Sherman could take Tunnel Hill. The advance would begin on signal from the artillery on Orchard Knob—six guns, fired at regular intervals. While preparations were being made, Grant went down behind the hill with General David Hunter, Dr. Edward Kittoe, and William Smith and sat on a log by a fire to have some lunch Smith had just brought from the headquarters cooks. After lunch they had a quiet smoke, then Grant went back up the hill to see what was happening.

So far, nothing at all had happened. It took time for orders to filter all the way down to the front line, an hour had passed since Grant told Thomas to make the assault, the afternoon was wearing away, and Grant was beginning to show signs of impatience—when, at last, the signal guns went off. There had been so much sporadic artillery fire all afternoon that the soldiers had trouble recognizing the six spaced reports, but in one way or another they got the word, and around half past three the officers on Orchard Knob heard a swelling roar of cheers coming up from the plain. For a few moments they could see nothing, because most of Thomas’ line was invisible from the hilltop; then the soldiers appeared, rank upon blue rank, forming up to face Missionary Ridge, flags in the wind, sunlight coming down from beyond Lookout Mountain to slant along the rows of bright muskets, and the final scene had opened.

Thomas was sending in four infantry divisions, 20,000 men or more—more men than Pickett had used at Gettysburg—and the charge was something to see. As the men marched forward, out in the open, a waiting Confederate wrote of “this grand military spectacle,” Grant remembered it as “the grand panorama,” and the mass of infantry swung forward, more than a mile from flank to flank, three double-ranked lines deep. General Phil Sheridan rode in front of his division, and he said afterward that he looked back just as the men broke into a run; the line suddenly became a crowd, all glittering with bayonets, and Sheridan was stirred by “the terrible sight” and hoped it would have a moving effect on the defenders who had to look at it. The advancing host brushed the Confederate skirmishers out of the way and kept moving on, and the long crest of the ridge ahead and above broke out with clouds of dirty white smoke slashed with flame as Bragg’s artillery went into action. A thinner haze came up along the rifle pits below as the Federals got into musket range, and now the open ground in front was all speckled and streaked with the bodies of men who had been hit. The charging mass came nearer and nearer, and here and there defenders broke from the trenches and ran back to the ridge; then the whole immense weight of the charging infantry swept into the pits and swamped them, the Confederates there either surrendered or ran, and Grant’s order to take the line at the foot of the ridge had been carried out.

And now Chattanooga produced its second immortal legend, fit to go with the tale about the battle above the clouds. Just here, according to the legend, this became the soldiers’ battle, the victory that got away from the generals and was won by the spontaneous valor of soldiers who led themselves. For instead of carefully re-forming their ranks and awaiting further word from headquarters, the men of the Army of the Cumberland stayed in the pits just long enough to get their breath and then moved on to storm Missionary Ridge itself. They came out of the trenches in knots and clusters, with ragged regimental lines trailing after the moving flags and a great to-do of officers waving swords and yelling, and then they went up the five-hundred-foot slope and broke General Bragg’s line once and for all and made his army retreat all the way back into Georgia.

The legend is that they did this on their own hook, fired up by the feeling that Grant considered them secondclass troops and needed to be shown a thing or two. In unromantic fact they made the attack for the most ancient and universal of military reasons—because their officers told them to. To be sure, the rifle pits made an unprotected target for the Confederate gunners, and as veterans these Federals could see that they would be safer climbing the ridge, where there was a good deal of dead ground, than they were here in the open. But the famous picture of four infantry divisions taking matters into their own hands and making a charge nobody had called for belongs with the picture of Hooker’s men scaling a vertical wall of rock under heavy fire: it makes a good legend but nothing more. The storming of the ridge came under orders.

The division on the left of the assault wave belonged to General Absalom Baird, and Baird reported that the staff officer who brought him Thomas’ order to advance told him that taking the rifle pits was just the first step in a general assault on the mountain, “so that I would be following his wishes were I to push on to the summit.” Next in line were Gordon Granger’s two IV Corps divisions, Thomas J. Wood’s and Phil Sheridan’s, and on the extreme right was the division led by General Richard W. Johnson. Johnson said he had been ordered to advance with the left of his division touching the right of Sheridan’s, and he was to conform to Sheridan’s movements. If Sheridan went up the slope, Johnson would go with him.

The legend seems to have been born with Granger and Wood. Granger felt that he was ordered merely to “make a demonstration,” and he said that once the rifle pits were taken, “my orders had now been fully and successfully carried out.” Wood agreed: “We had been instructed to carry the line of intrenchments at the base of the ridge and there halt.” Granger said the men went up the slope without orders, “animated with one spirit and with heroic courage,” and Wood wrote that “the vast mass pressed forward in the race of glory, each man anxious to be first on the summit.”

Actually, these remarks prove nothing except that corps and division commanders do not always know what is going on in the combat zone. Wood had two of his brigades in front, and the commander of one of them, General August Willich, said that he had understood all along that they were to storm the crest; not until after the battle did he learn that they were supposed to stop when they had taken the rifle pits. The other brigadier, William B. Hazen, said his orders were to halt once the pits had been occupied, but the artillery fire from above was so severe that “the only way to avoid destruction was to go on up … the necessity was apparent to every soldier of the command.” So, after giving his men five minutes to get their breath, he ordered them to go on up the slope. The third brigadier in Woods’s division behaved as Hazen did, sending his men forward simply because he saw they could not stop in the rifle pits.

That leaves Sheridan. When his men swept into the rifle pits, Sheridan suddenly realized that his orders were vague and that he did not know whether he was to stop here or go on. He sent an aide galloping back to Orchard Knob to find out, and during the aide’s absence some of Sheridan’s regiments went beyond the pits to find more sheltered ground at the base of the ridge and on the slope; whereupon Sheridan got the idea that the only solution was to keep going forward. When the aide returned, with Granger’s order to halt, Sheridan cried: “There the boys are, and they seem to be getting along; stop them if you can; I can’t stop them until they get to the top.” Then Sheridan rode along the line, waving his hat in one hand and his sword in the other, calling at the top of his voice: “Forward, boys, forward! We can go to the top!” He came to a dirt road that went snaking its way up toward the crest, started his horse up the road, and yelled: “Come on, boys, give ’em hell! We will carry the line!” So Sheridan’s men went forward, and the officers back on Orchard Knob realized that all four divisions were going straight on up Missionary Ridge.

The advance across the plain had been orderly, a broad mass of soldiers trotting ahead in trim military formation, closing ranks automatically as the Confederate gunners took their toll. The charge up the ridge was complete disorder. The men went up in groups, one regiment here and another there, the flag always at the front, and there was nothing resembling a regular battle line—on a slope so steep and broken, there could not be a formal line. A number of little roads like the one Sheridan found led up to the crest, and many of the regiments followed these. Others threaded their way up shallow ravines that furrowed the slope, taking advantage of the protection the hollow ground offered. In one way or another, most of the little columns found a good deal of shelter; their heaviest losses came earlier, down on the open ground, and though it took a brave man to make this ascent, the going was not as bad as it looked.

The general lack of order seems to have worried Grant a little, just at first. Quartermaster General Meigs was Standing beside him, and as the long climb began, he said Grant told him this was not quite what he had ordered. As Meigs remembered it, Grant said that “he meant to form the lines and then prepare and launch columns of assault, but as the men, carried away by their enthusiasm, had gone so far, he would not order them back.” Granger’s chief of staff said that Grant asked Thomas who had ordered this charge, and when Thomas replied that he had not, Grant muttered that somebody would catch it if the charge failed; after which he clamped his jaw on his cigar and watched in silence.

It became clear, at last, that this incredible attack was going to succeed. On top of the ridge, Confederate Hardee saw the tide coming in and sent word over to Cleburne to bring all the men he could spare to the center because the Yankees were pressing hard—Grant’s notion that an attack here would weaken the Confederate line in front of Sherman was not too far off, after all. Cleburne took two brigades and came down the ridge, but before he could get to the center the Confederate line had been broken and he could do no more than draw a line across the ridge, facing south, to keep the Federals from driving north to destroy his own command.

Astoundingly, and against the odds, the charge was a swinging success. Grant had given himself two chances and one of them had worked; the impregnable line had collapsed when Thomas swung his hammer and the Confederates had lost the battle, the mountain barrier to the deep South, and all chance of recovering Tennessee. Scribbling his story of the fight, General Meigs summed it up with breathless enthusiasm: “Invasion of Tennessee and Kentucky indefinitely postponed. The slave aristocracy broken down. The grandest stroke yet struck for our country. … It is unexampled—another laurel leaf is added to Grant’s crown.” Both victors and defeated were amazed by what had been done, and it is clear that even though the assault had not been the spontaneous, grass-roots explosion that it soon became in legend, something remarkable had happened when the officers told the men to go up the steep mountainside. Charles Dana assured Secretary Stanton that “the storming of the ridge by our troops was one of the greatest miracles in military history,” and the soldiers themselves felt the same way. On the crest of the captured ridge, Union soldiers yelled and straddled the captured cannon, “completely and frantically drunk with excitement,” hardly able to believe that they had done what they had done. Long afterward, one of them wrote: “The plain unvarnished facts of the storming of Mission Ridge are more like romance to me now than any I have ever read in Dumas, Scott or Cooper.” Dana expressed the simple truth when he said that “No man who climbs the ascent by any of the roads that wind along its front can believe that men were moved up its broken and crumbling face unless it was his fortune to witness the deed.”

That evening a worker for the Christian Commission, visiting a field hospital, asked a wounded Federal where he had been hurt. “Almost up,” replied the soldier. The Commission man explained that he meant “in what part are you injured?” The soldier, still gripped by the transcendent excitement of the charge, insisted: “Almost up to the top.” Then the civilian drew back the man’s blanket and saw a frightful, shattering wound. The soldier glanced at it and said: “Yes, that’s what did it. I was almost up. But for that I would have reached the top.” He looked up at the civilian, repeated faintly, “Almost up,” and died.