Reagan's commitment to deregulation, aggressive military spending, and diminished oversight created an appearance of corruption that some critics claimed was worse than Watergate.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

A modest man in his habits and attitudes, Ronald Reagan did not succumb to greed himself. In fact, he conducted himself in a remarkably simple, often abstemious, manner as president. Reagan did not profit from the presidency, and he sought — with the notable exception of the illegal Iran-Contra maneuvers — to act within the constitutional expectations of a public servant accountable to the other branches of government and, ultimately, to the American people.

Reagan's dislike of government regulation, however, enabled a pervasive diversion from strict ethical rules of conduct within his administration. There were fewer daily checks from the Oval Office on self-interested behavior among various aides. The President trusted his loyalists, and he empowered them to act with little oversight. Although he followed a strong personal ethical code, Reagan did not articulate one for those who worked around him.

Reagan's negligence in promoting ethics among his subordinates made his administration the most scandal-ridden since Watergate. At times, it appeared to replay some of that same history, with televised congressional investigatory hearings and serious talk of impeachment. In contrast to Nixon, however, Reagan was generally a law-abiding president. Yet he did not punish (and he sometimes rewarded) those around him who flagrantly broke the law. As a result, numerous prominent Reagan administration officials were convicted of crimes, some went to jail, and many ended their careers in disrepute. Independent Counsel investigations and prosecutions multiplied throughout his term in office.

The gravest irony of the Reagan administration was that its aversion to big government swelled the coffers of those privileged officials who controlled government. Managerial negligence and deregulation encouraged corruption and lawbreaking. Anti-communist zeal powered unconstitutional militarism. The government did not diminish in size during Reagan's presidency, but instead grew larger than before. And it became less tethered to the law.

The Iran-Contra Affair

The biggest scandal of the Reagan years, and the most significant constitutional crisis since Watergate, was the Iran-Contra affair. In the spring and summer of 1987, millions of Americans watched forty-one days of televised joint hearings from the House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran and from the Senate Select Committee on Secret Military Assistance to Iran and the Nicaraguan Opposition. The “Iran-Contra Hearings'', as they were called, had all the elements of made-for-television drama: powerful elected representatives, eloquent defenders of constitutional checks and balances, zealous anti-communists, and attractive supporting actors.

The tangled web of illegal activities that connected Washington, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua, and other countries was often hard follow, but the plotline was evident: high-level figures in the Reagan administration, perhaps including the President, had broken numerous laws to pursue deeply held foreign policy goals. The key question was not whether they had acted illegally, but who should be punished and how.

From its first days in office, the Reagan administration prioritized reversing perceived advances by communist regimes, supported by the Soviet Union and Cuba, in Central America. William J. Casey, Reagan's former campaign manager and Director of Central Intelligence, focused immediately on Nicaragua — a small, strategically located country on the Central American isthmus with a pro-Cuban and pro-Soviet government (under the Sandinista Liberation Front) that came to power in 1979 following the overthrow of longtime pro-American dictator Anastasio Somoza. Casey and others in the U.S. government were alarmed by the spread of communist influence, which they ascribed to President Carter's weak policies, and they believed that a Nicaraguan counterrevolutionary paramilitary force, the “Contras,” could lead a region-wide reversal, beginning in this small country.

In 1981, the CIA began secretly channeling weapons and money to the Contras. When Casey reluctantly shared this information with Congress a year later, the House of Representatives placed restrictions on U.S. aid. Representative Edward P. Boland, a Massachusetts Democrat, authored the first of a series of amendments to federal appropriations, which prohibited the use of covert resources to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The amendment passed the House (unanimously) and the Senate and President Reagan signed it into law.

Despite these restrictions, the CIA and the U.S. military increased their support for the Contras, claiming dishonestly that the aid was not signed to overthrow the Sandinista regime. In 1983, CIA-supplied aircraft bombed the Sandino Airport near Nicaragua's capital. In 1984, CIA helped the Contras mine the main harbors of Nicaragua — a violation of international law for which the International Court of Justice ruled against the United States.

These escalatory actions, combined with news coverage of human rights atrocities committed by the Contras and their supporters in neighboring Honduras, motivated Congress to introduce more restrictive legislation. A new Boland amendment, passed by the House and Senate in late 1984 and signed by President Reagan that December, prohibited all military assistance to the Contras or other groups in and around Nicaragua. The Reagan administration had defied congressional intent since 1982; after 1984 continued aid to the Contras was clearly illegal.

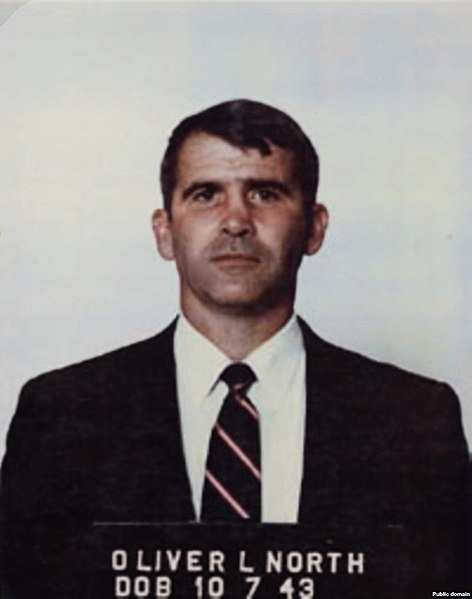

The center for U.S. strategy toward the Contras was the National Security Council (NSC), located in the White House, staffed by Robert C. McFarlane, Admiral John M. Poindexter, and Lieutenant Colonel Oliver L. North, among others. These men believed that President Reagan wished to continue funding the Contras despite congressional prohibition. McFarlane also responded to Reagan's personal demand to help secure the release of American hostages held in the Middle East despite a stated U.S. policy of not negotiating with terrorists. These two priorities — continued support for the Contras and the negotiated return of American hostages — merged in the NSC as a secret illegal plan for arms sales to Iran (the sponsor of many hostage-taking groups in the Middle East) and diversion of the revenue from the Iranian arms sales to the Contras.

Diverting weapons and cash across two continents required a long chain of secret deals with shady arms dealers, mercenaries, money changers, drug runners, and terrorists. The White House worked with all of these groups as it lied to Congress and the American people. American anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, originally sent to Israel, made their way to Iran, and cash for the diversion of those missiles made its way to dictators in Panama and Honduras. These figures in turn skimmed off their share of the funds before sending what was left to the Contras. The U.S. military then, at White House request, replenished the weapons Israel had diverted. This was American-sponsored organized crime.

The revelation of these facts by enterprising journalists led to the joint congressional Iran-Contra hearings, preceded by a special review board (the “Tower Commission,” named after its chairman, Texas Republican Senator John G. Tower), whose findings were preliminary and based on limited investigation. In December 1986 a panel of three judges from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit — empaneled as a Watergate-era check on executive abuses — appointed an Independent Counsel, Lawrence E. Walsh.

Over more than six years, he and his team of lawyers unraveled the lurid details of hidden NSC conversations, exotic CIA meetings, and repeated cover-ups rising to the level of the President himself. Reagan knew about the arms sales to Iran, which, at the very least, violated the Arms Export Control Act. Reagan also knew that his staff was continuing to support the Contras despite the Boland amendments — although it is not clear that the President understood how money from the Iranian arms sales was making its way to Nicaragua. Like many of his closest advisers, Reagan lied to Congress and the American people when he falsely claimed he was unaware of nearly everything.

Walsh chose not to prosecute the president, especially in light of Reagan's declining health after he left office. He also chose not to prosecute Vice President George H. W. Bush, who became President after Reagan. Walsh charged fourteen high-level officials with criminal behavior, including McFarlane, Poindexter, North, Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger, and Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams. In a move that echoed President Gerald Ford's pardon of Richard Nixon, President Bush pardoned Weinberger, Abrams, and three others on Christmas Eve 1992 — just before the end of his presidency.

The Iran-Contra Affair embodied the profound and systemic ethical lapses at the heart of the Reagan administration. The President did not benefit personally from the lawbreaking around him, but he did almost nothing to stop it. Out of greed and zealotry, his closest advisers repeatedly broke the law, lied to Congress, and stole government funds. More than one hundred high-level Reagan administration officials faced prosecution, and more than $130 billion was embezzled. Reagan's commitment to deregulation, aggressive military spending, and diminished oversight created a cocktail of corruption that was, in many ways, worse than Watergate.

Copyright © 2019 by The New Press. Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.