Muir struggled for decades to create and protect Yosemite National Park, and helped launch the American environmental movement.

-

September 2023

Volume68Issue6

Editor's Note: Dean King is the author of twelve books, including, most recently, Guardians of the Valley: John Muir and the Friendship that Saved Yosemite, from which he adapted this essay. More information about King and his books is at: www.deanhking.com.

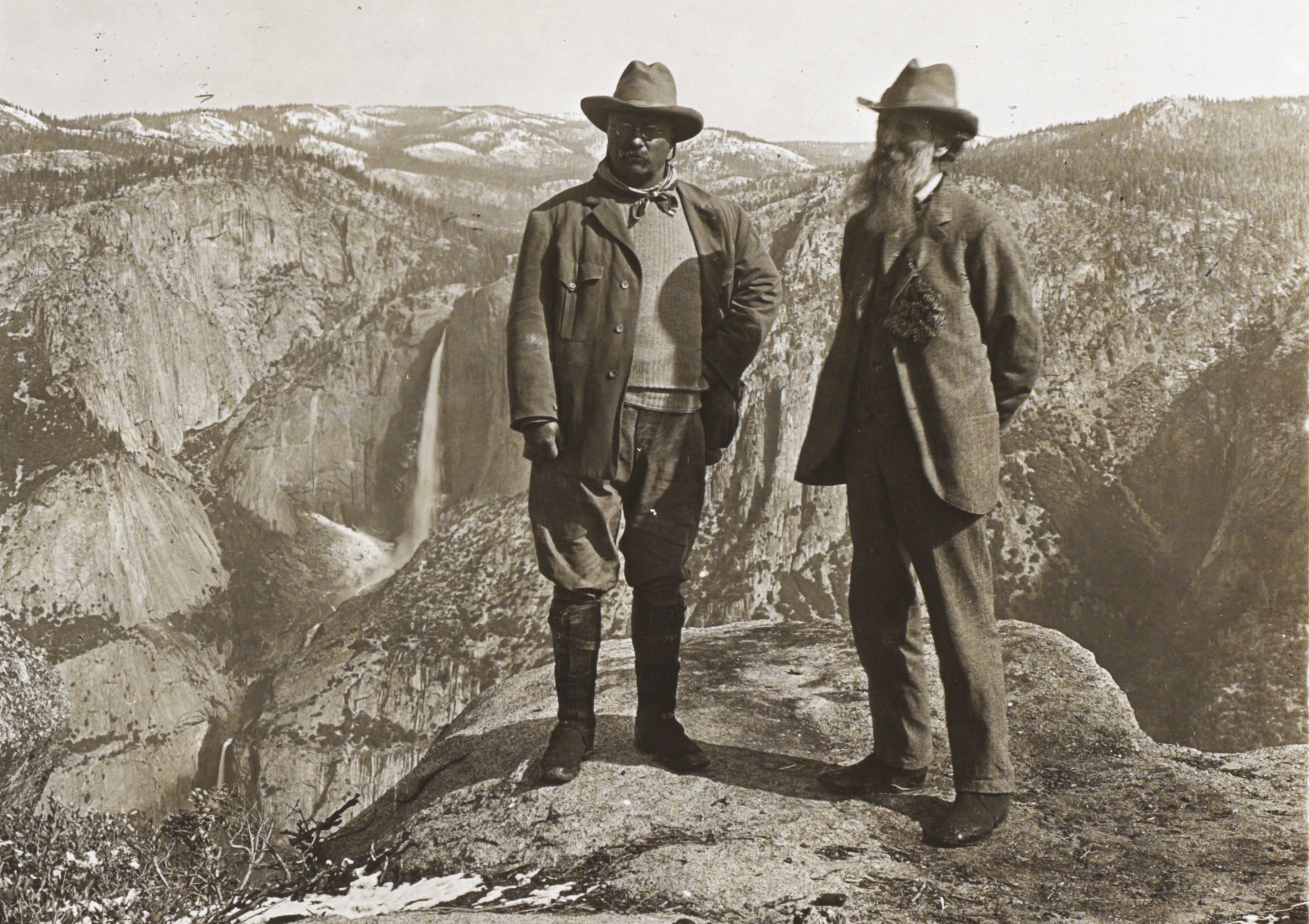

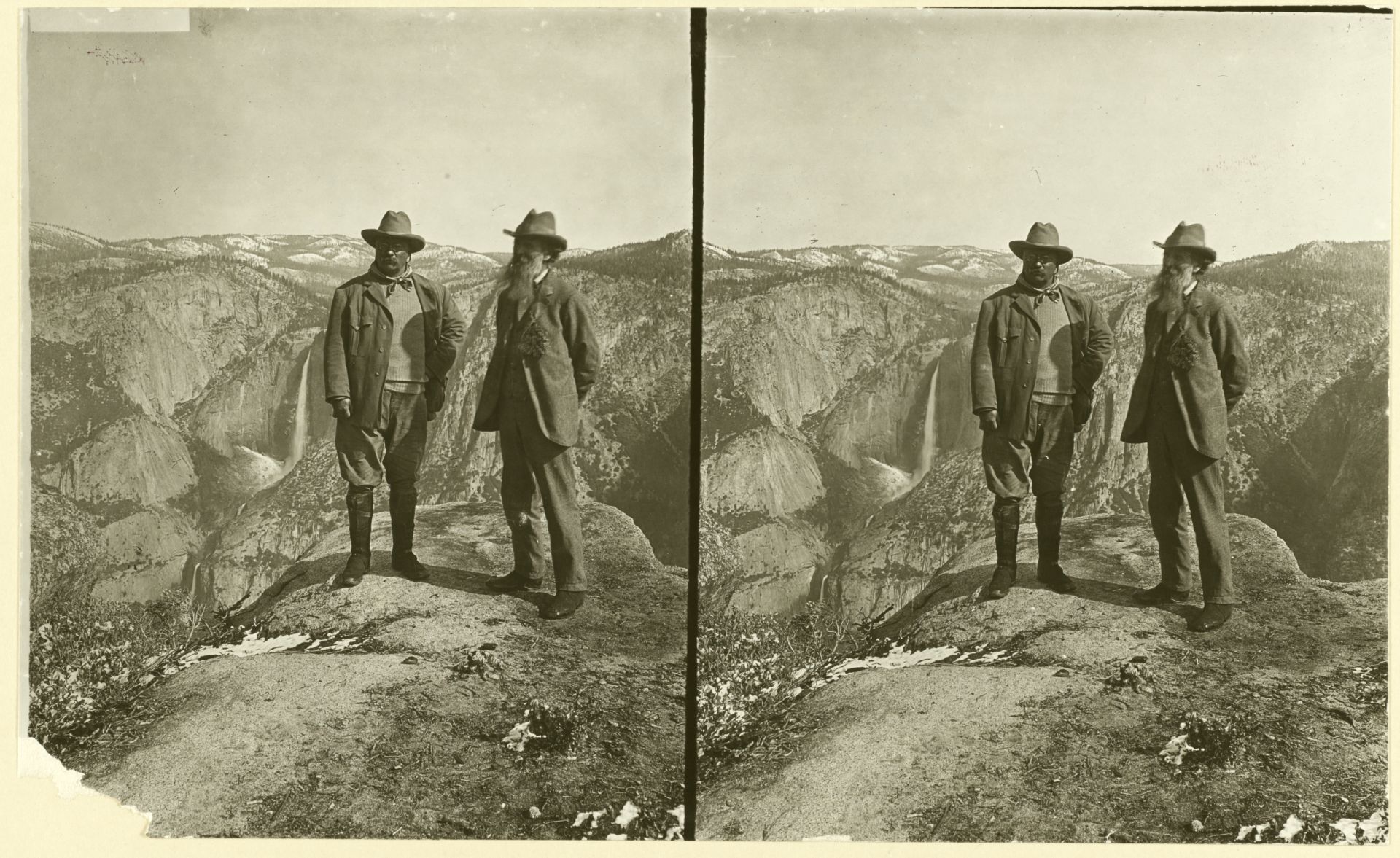

Whether the anonymous photographer felt the conceivably immense pressure, we will never know. But, with the head of the nation and the soul of its preservation movement – both rugged, demanding, and outspoken men – paired together for a brief time, posed against one of the nation’s most transcendent and iconic landscapes, after the president's long journey by train, horseback, and on foot, the stakes in making a good image were high.

The photograph — the official portrait of John Muir, age 65, and Theodore Roosevelt, age 44, at Overhanging Rock — would come to symbolize the young president’s love of nature and would serve as a memorial to the meeting of the two indomitable men who had camped there together the night before. Yet all might not have been as copacetic as it appeared, or as Roosevelt, who was laying the groundwork for his campaign for a second term, would later lead us to believe.

The Roosevelt-Muir photo op took place in 1903, five decades after the California Gold Rush, when the first white men to enter the magnificent valley — the Mariposa Battalion, a volunteer army of prospectors, ranchers, and roughnecks led by the trader James Savage, who had quarreled with the local Miwuk Indians — went there in the spring of 1851 to rout the tribe from its stronghold, a remote valley and bear den they called Yosemite.

Reaching what became known as Inspiration Point, at least one of them, the gold miner L. H. Bunnell, realized the specialness of this place: “Haze hung over the valley — light as gossamer — and clouds partially dimmed the higher cliffs and mountains,” he explained. “This obscurity of vision but increased the awe with which I beheld it, and, as I looked, a peculiar exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears with emotion.”

Four decades had passed since President Lincoln had signed a bill granting Yosemite (Miwuk for “those who kill”) Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State of California to preserve and protect “for public use, recreation, and enjoyment, inalienable for all time.” This Yosemite grant, preceding the creation of Yellowstone National Park by eight years, was the first to establish American-government protection of any land.

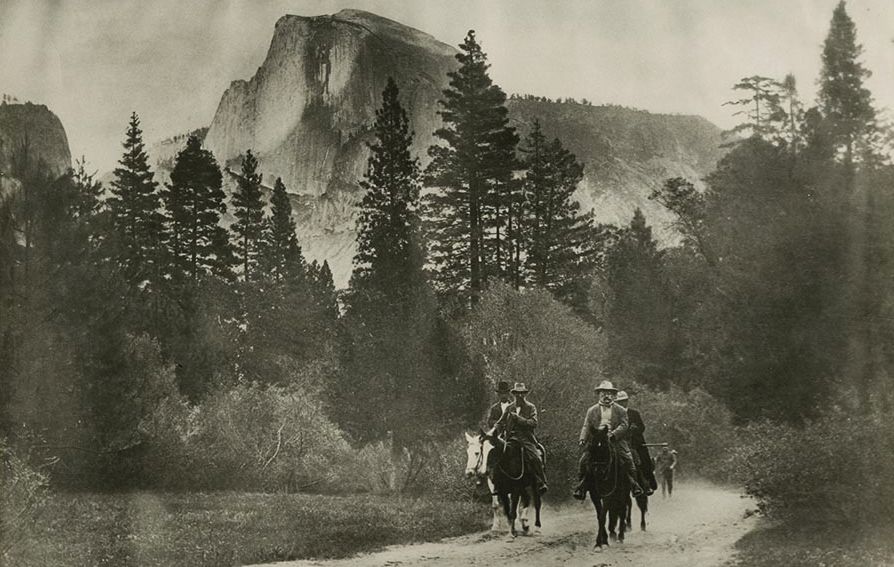

Lincoln’s little-observed act in the midst of the Civil War would become the fountainhead of the nation’s conservation movement, and John Muir, its champion, the embodiment of the nation’s passion for its wilderness. It was not by accident that Roosevelt, on a two-month, twenty-five-state, 200-speech, whistle-stop tour of the West that was meant to boost the electoral viability of the youngest president ever, came to meet Muir at this time and in this place.

These two men, for very different reasons, at least had the insight to know that they had to put a stop to the devastation that white men had brought to the land. That was their fight. This was their summit. There was a real sense that Yosemite Valley, which they explored, represented the natural beauty of the nation and that its fate would somehow define America’s future.

The night before the photo was taken, Muir and Roosevelt camped with their guides near the upper end of the valley, a couple miles from Glacier Point, where Overhanging Rock juts out and gives a spectacular view of the mile-deep Yosemite Valley and the panoramic Sierra Nevada mountain range. Roosevelt was already well into his cross-country tour, and was eager to escape the coffin-like luxury of his plush Pullman railcar, along with the ever-present phalanx of reporters and the endless pressure to perform and please at every stop.

Since his years as a Dakotas rancher and lieutenant colonel leading the Rough Riders cavalry regiment in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, he preferred horseback to a reclining cushioned seat. After a satisfying day of riding their mounts through deep snowdrifts, the men lay beside the campfire on beds made from the bent boughs of a fir tree (T.R. also had 40 blankets provided for him) and, both being capital storytellers, rattled away, neither hesitant to speak his mind.

Muir found much to like in the “interesting, hearty, and manly” Roosevelt, but he mistrusted his motivations for preserving nature and his interpretation of what might constitute “the greatest good for the greatest number,” the mantra of the president’s forestry chief, Gifford Pinchot. When Roosevelt bragged about his hunting exploits, Muir, angered by America’s heedless eradication of the passenger pigeon and the American buffalo, chastised him for killing animals for sport.

“Mr. Roosevelt, when are you going to get beyond the boyishness of killing things?” Muir blurted out. “It is all very well for a young fellow who has not formed his standards to rush out in the heat of youth and slaughter animals, but are you not getting far enough along to leave that off?”

Though Roosevelt lacked any remorse when it came to slaying animals, he was a consummate diplomat when he wanted to be, and he considered the point. “Muir,” he responded at last, “I guess you are right.”

It was a dubious concession. Roosevelt had collected and stuffed more than a thousand birds by the time he went off to Harvard College in 1876. He had left his pregnant wife to rush out to the Badlands to shoot a buffalo, a species on the brink of extinction, before it was too late to bag one, and on this train tour twenty-seven years later, he was barely persuaded by his handlers not to dog-hunt cougars in Yellowstone, where hunting was forbidden, for fear of a public outcry.

While Roosevelt would never escape his chest-thumping glee over the kill, Muir, a hunter in his youth in Wisconsin, had long since rejected the notion that wild animals were created solely for food, recreation, and “other uses not yet discovered,” and he once wrote in his journal that, if a war broke out “between the wild beasts and Lord Man, I would be tempted to sympathize with the bears.”

Perhaps they would not see eye to eye on hunting, but Muir had trees and whole ecosystems to save. Blinded by its own hubris, the nation was grotesquely cannibalizing itself, felling giant sequoias, some of the planet’s oldest and largest organisms, thousands of years old, and even shipping them off to be exhibited in monstrous fashion, like circus spectacles. The irony was that they would have to undo Lincoln’s grant in substance to save it in spirit. Muir and his co-conspirator, his editor at the Century Magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson, felt in their hearts that this bold, and, in many circles, unpopular, maneuver was necessary.

With its spectacular scenery and well-heeled tourists, Yosemite had attracted some of the country’s most skilled photographers. Though this one — a hired hand sent by Underwood & Underwood, the world’s largest publisher of stereo views — would go unnamed, perhaps it was Arthur Pillsbury, a company stringer, who had made a photo of T.R. and Muir two days earlier in front of the immense sequoia Grizzly Giant. Whoever it was clearly knew the precise place and time to produce a memorable image. “Sunrise from Glacier Point!” Muir’s late friend and the geologist Joseph LeConte had once exclaimed. “No one can appreciate it who has not seen it…. I had never imagined the grandeur of the reality.”

Before breakfast, in the soft morning light, Roosevelt and Muir took their places by the cliff’s edge at Glacier Point, with a view across the valley as a backdrop. Though neither cared much for sartorial splendor, they both looked kempt in their hats and jackets. Roosevelt wore jodhpurs and boots, Rough Rider-fashion, with a kerchief around his neck. Muir wore a simple broadcloth suit.

In the photo, there’s no hint that they had refused tents to sleep by the campfire, and that five inches of snow had dropped on them overnight, a Sierra Nevada baptism verifying that the president had indeed escaped pampered civilization and the claws of his handlers to be immersed in the bosom of nature, notwithstanding the fact that he had a mountain of blankets to keep him warm.

“We lay down in the darkening aisles of the great Sequoia grove,” Roosevelt later wrote in his autobiography. “The majestic trunks, beautiful in color and in symmetry, rose round us like the pillars of a mightier cathedral than ever was conceived even by the fervor of the Middle Ages.”

Roosevelt and Muir had sheltered without tents in a fir-fringed meadow, where they cooked their supper — steak and coffee — over an open fire. It was a far cry from Muir's usual meal of bread and meat juice. The president, not even knowing how much better he had it, still declared: "Now, this is bully!"

At dawn, Roosevelt emerged from his thicket of army blankets; he shook off the additional blanket of snow and shaved by the light of the campfire. “This is bullier yet! I wouldn’t miss this for anything,” he exclaimed.

The group made their way to Overhanging Rock, which jutted out precipitously and, from certain angles, looked only a footstep away from Yosemite Falls all the way across the valley. Half Dome stood stark against the sky. To Muir, it looked “down the valley like the most living being of all the rocks and mountains,” such that one could “fancy that there were brains in that lofty brow.” The promontory provided just the right perspective on the Giant Staircase, the impressive drop of the Merced River into the valley over the 594-foot Nevada Fall (Wowywe, or “twisted current,” to the Miwuk) and, just downstream, the 317-foot Vernal Fall (Yanopah, “little cloud”). The view stirred the president.

Casting his eyes now on what many believed was the most spectacular panorama in the nation, the nation that he led, Roosevelt felt a welling of emotion. Not only was it a sight of awesome beauty and grandeur; it was an immense responsibility. Though, if tears streaked his face, as was reported, you would never know it from the photo. The photographer, who took two shots of the pair and two of Roosevelt alone, made sure of that.

The man who took the shot oriented the distant Yosemite Falls — a flowing white streak — on the left-hand side of the frame, below Roosevelt’s right shoulder. Nature was the great equalizer, but he placed Roosevelt, who was five feet, eight inches tall, on the higher part of the boulder, with his broad shoulders square to the camera. He positioned Muir, who was a few inches taller (and, with his thin build, looked even more so), at an angle a little lower on the right. The men were thus as evenly matched in height as in stature, each being master of his own realm.

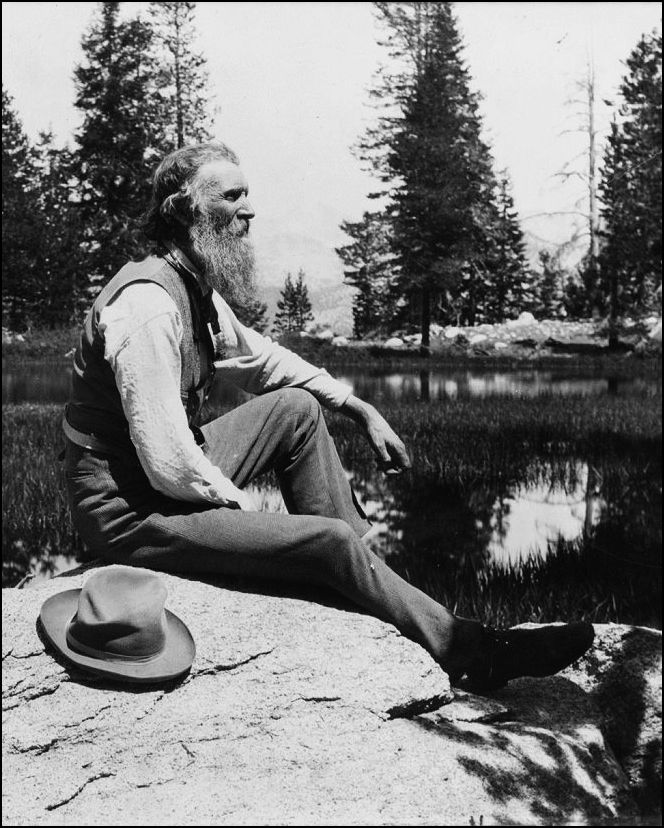

Roosevelt looked boldly into the lens, as if daring the viewer to question him. Muir, lithe and erect of posture - even when he was in his seventh decade - bushy-bearded, gazed pensively, hands deferentially clasped behind his back, as if he were pausing in the middle of a conversation with the president. He had embellished himself, as he liked to do, with a botanical spray as a boutonniere.

Muir saw Roosevelt as the best hope to prevent the American wilderness from being swallowed whole by a voracious nation whose appetites and aspirations were fueled by its natural resources. In 1892, Muir and a group of other concerned citizens had gathered in San Francisco, after the destruction of what was believed to be the largest tree ever cut down, the massive General Noble Tree — 3,200 years old, 312 feet tall, and 99 feet around.

They voted to create a club to explore, enjoy, and make accessible the mountain regions of the Pacific Coast, to publish information about them, and “to enlist the support and cooperation of people and the government in preserving the forests and other natural features of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.”

The vote for the president of the Sierra Club went unanimously to John Muir. It was more than just his reputation and intellect that united the members. An environmental organization could have no greater figure at its helm. Although it should be noted that Muir, who possessed more than a touch of Scottish misanthropy (for all humanity), occasionally used sharp words and offensive period vernacular, particularly regarding American Indians and black people.

But the deep conviction that had fired his evangelical father also burned within Muir, making him a natural leader, a philosopher king. In a sense, he preached through nature and through his deep belief that nature would prevail. Ralph Waldo Emerson's Transcendentalist writings had been a huge influence on the younger Muir.

Muir had been waging a lonely war in California against the commercial interests that were exploiting and destroying the forests, rivers, and mountains. Although he had earlier resisted a leadership role in such a club, he was now surrounded by this very encouraging and capable band of friends and allies, and he accepted the mantle.

The group would face its toughest test just after the turn of the century. San Francisco had become a cosmopolitan city of more than 400,000 people when, on April 18, 1906, a sudden spasm shook the city at 5:12 in the morning. The ground rocked and bucked for forty-five seconds. Shocking as this was to the people thrown out of bed or losing their balance on the predawn streets, it was only the foreshock of the main earthquake. After a brief pause — ten or twelve seconds — what would soon be dubbed the Great San Francisco Earthquake began in earnest. The pavement pulsated as if it were alive. Horses reared in terror and bolted. The ground undulated like a jump rope — whipping four to five feet per second — and, as it repeatedly rose and fell, the surface was lacerated, as if by an invisible knife. Buildings swayed like trees in a storm. The lacerations grew into gaping fissures.

The rumbling, rending, and tumbling was just the beginning. There would be more than 150 aftershocks, some of them major, over the next two days. Small fires erupted from damaged chimneys, overturned stoves, severed electric wires, and ruptured gas mains.

The earthquake fractured or crushed the conduits carrying water into the city and destroyed hundreds of water mains. Firemen attaching hoses to hydrants often found a weak stream that quickly faded to nothing at all.

The dozens of individual fires soon combined into three enormous blazes. High winds were the enemy, spreading the flames with shocking speed. The three blazes soon united into one raging nightmare of a firestorm. With temperatures surpassing 2700 degrees Fahrenheit, metal and brick disintegrated, while a dense black fog turned day into night.

In four days, 25,000 buildings and 500 city blocks across four square miles burned to the ground. More than 3,000 people died, and hundreds of thousands were left homeless. The property-damage losses were approximately $500,000,000. To this day, it ranks as the second-deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history (after the Galveston hurricane of 1900).

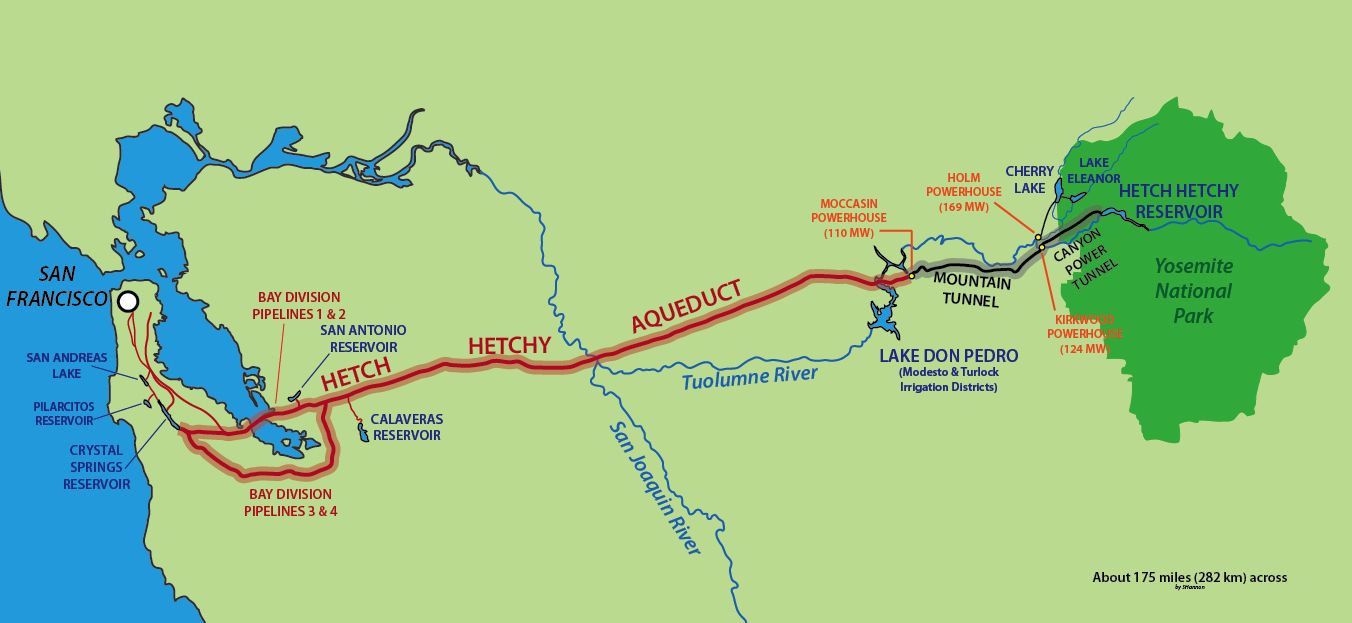

The catastrophic fires led to a clamor to dam Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy valley to supply water to San Francisco. Muir and his allies fought with editorials and testimony at various hearings. “The roof of the Sierra is about 500 miles long, but these schemers, for financial reasons, seem to think that only the Yosemite portion, used as a National Park, is available to quench the thirst & prevent it from being burned up a second time,” complained Muir in a letter to President Roosevelt.

But San Francisco corporate and city interests kept up the pressure during the hearings in Congress. In the January 1909 issue of The Century, Muir made an emotional appeal, describing Hetch Hetchy’s landmarks, including the granite dome of Kolana Rock, “a majestic pyramid” soaring more than two thousand feet, and, across from it, Tueeulala Falls, plummeting 600 feet to a ledge — the most beautiful falls he had ever seen — with its “airy, swaying grace of motion and soothing repose.”

Nearby Wapama Falls plunged 1700 feet, roaring and booming in gorge shadows like an avalanche. Though Hetch Hetchy’s “walls are less sublime in height than those of Yosemite, its groves, gardens, and broad, spacious meadows are more beautiful and picturesque. It ought to be faithfully guarded.”

“It seems incredible that so barbarous a step backward as the destruction of a Yosemite Valley could possibly be taken by Congress,” Muir would write. But Congress would eventually pass an authorization, which Woodrow Wilson signed into law in 1913. The New York Times decried the bill, which “converts a beautiful national park into a water tank for the City of San Francisco… Is it time for real conservationists to ask, ‘What next?’”

The following year, after contracting pneumonia while visiting his daughter Helen, Muir died in Los Angeles on Christmas Eve. Some claim that he died of a broken heart because of Hetch Hetchy, but Muir remained resolutely optimistic that people would do the right thing and, in all probability, he died firm in his belief that, one day, it would be set free again.

Muir had written what could be a fitting epitaph for himself in the preface to his book Our National Parks in 1901: “I have done the best I could to show forth the beauty, grandeur, and all-embracing usefulness of our wild mountain forest reservations and parks, with a view to inciting the people to come and enjoy them, and get them into their hearts, that so, at length, their preservation and right use might be made sure.”

Muir’s legacy, as a father of our national parks, founder of the Sierra Club, and spiritual leader of the environmental movement, continued to grow after his death. He is now widely hailed as the nation’s most influential conservationist. In 1908, in Marin Country, across from San Francisco, a lovely old-growth redwoods area near Mt. Tamalpais was designated as Muir Woods National Monument. Then, in 1915, the year after he died, California created the 210-mile John Muir Trail, from Yosemite Valley to Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the continental United States.

In 1976, the California Historical Society voted Muir “the Greatest Californian.” Congress declared April 21, 1988, John Muir Day in honor of his 150th birthday, and, that same year, the Golden State designated April 21 as the annual John Muir Day “to observe the importance that an ecologically sound natural environment plays in the quality of life of us all, and, indeed, the future of our existence.”

Portions excerpted from Guardians of the Valley by Dean King by permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2023 by Dean King. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.