The "People's House" has long been shaped by the visions and priorities of its occupants, from Jefferson’s colonnades to Truman’s monumental gutting.

-

Winter 2026

Volume71Issue1

Editor's Note: Stewart McLaurin is president of the White House Historical Association, and author of James Hoban: Designer and Builder of the White House. A version of this essay first appeared on the WHHA website.

The White House serves numerous functions: home to the president and his family, office for the president and his staff, ceremonial stage on which our nation welcomes its most important visitors, and a museum that welcomes over 500,000 visitors every year.

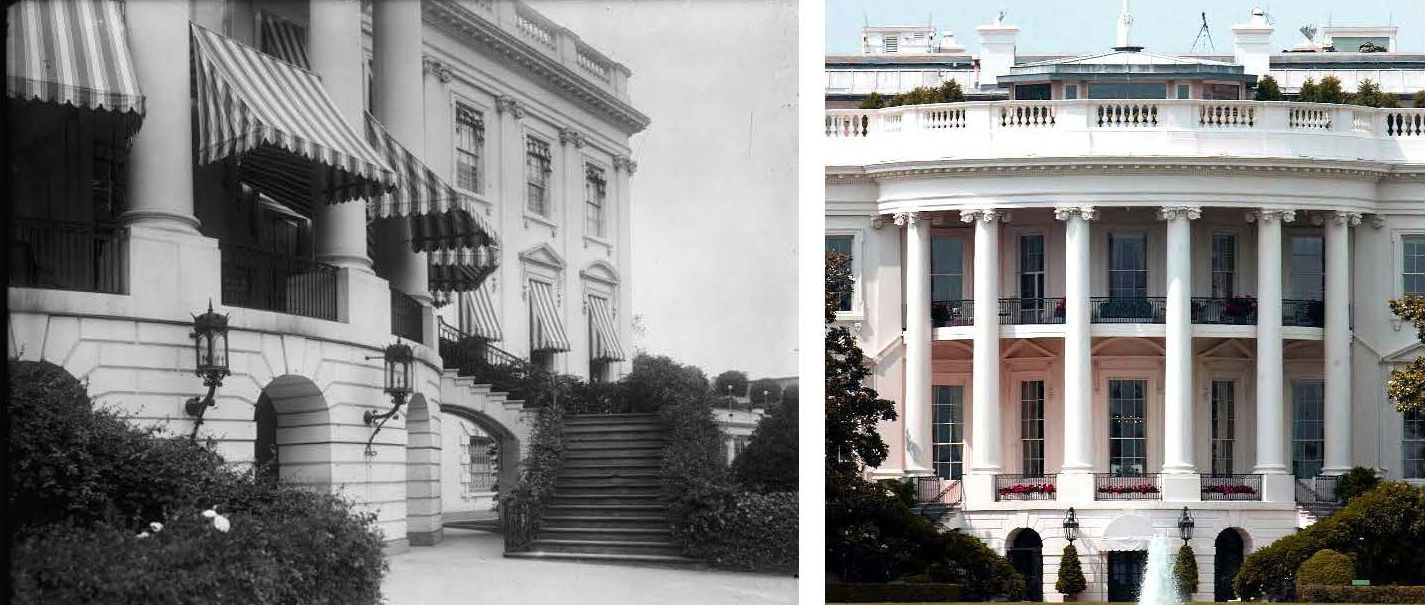

The current changes are only the latest transformations that this iconic building has undergone since its construction began in 1792. These alterations, driven by the practical needs, personal tastes, or political motivations of presidents and their families, have often sparked controversy, drawing scrutiny from the media, Congress, and the public, who view the building as a symbol of national heritage.

Significant changes to the White House have included Thomas Jefferson’s colonnades, Theodore Roosevelt’s West Wing, Franklin Roosevelt’s East Wing, Harry Truman’s balcony and the monumental gutting of the White House, Jacqueline Kennedy’s Rose Garden, Richard Nixon’s press briefing room, the evolution of the East Room and State Dining Room, the transformation of the Lincoln Bedroom, Bill Clinton’s closure of Pennsylvania Avenue, the White House fence height increases, and other historic examples such as Andrew Jackson’s North Portico and Chester Arthur’s opulent redecoration.

Examining these transformations provides context and precedent for more recent changes and adaptations.

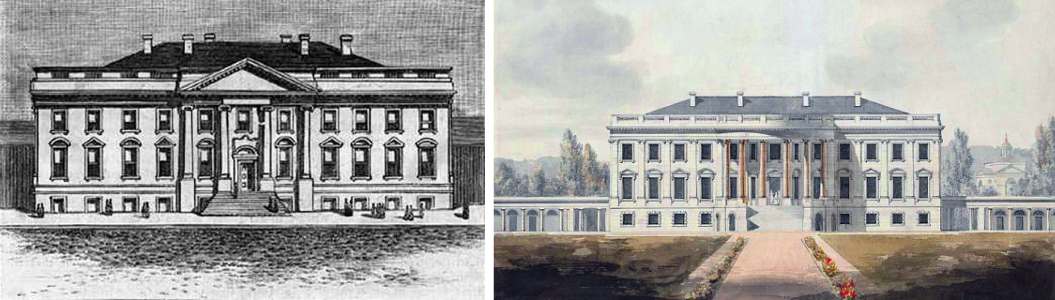

Jefferson's Colonades

Thomas Jefferson, the third president and an accomplished architect, envisioned the White House as a reflection of classical ideals. During his presidency, he added the east and west colonnades to connect the main residence to service buildings, enhancing both functionality and aesthetic symmetry. These covered walkways, inspired by Palladian architecture, facilitated staff movement and added a refined architectural element to the White House.

Jefferson’s colonnades faced immediate criticism for their cost and perceived extravagance. The National Intelligencer published editorials questioning the necessity of such embellishments for a government building, especially given the young nation’s financial constraints. In Congress, Federalist opponents argued that Jefferson’s alterations reflected aristocratic tendencies, clashing with the democratic simplicity the White House was meant to embody. Nevertheless, the colonnades proved durable and functional, becoming integral to the White House’s layout.

Jackson's Portico

Under President Andrew Jackson, the White House gained one of its most iconic features: the North Portico. Added in 1829–1830, this grand entrance, designed by architect James Hoban, addressed the building’s lack of a formal entryway on its northern side. The portico, with its imposing columns, aligned with the South Portico also added by President James Monroe after the original White House was rebuilt from the British fire, and gave the White House a more balanced and stately appearance.

The North Portico’s construction, for which Congress appropriated $24,729 (approximately $850,000 today), was controversial due to its being proposed during a period of economic downturn. The United States Telegraph criticized Jackson for prioritizing grandeur over the needs of ordinary citizens, portraying the portico as a symbol of his populist yet paradoxically lavish presidency. In Congress, Whig opponents questioned the expenditure, arguing that the funds could have been better spent on infrastructure or debt reduction. Some critics also felt the portico’s classical design was too ostentatious for a democratic republic. Nevertheless, the North Portico became a defining feature, now synonymous with the public face of the White House.

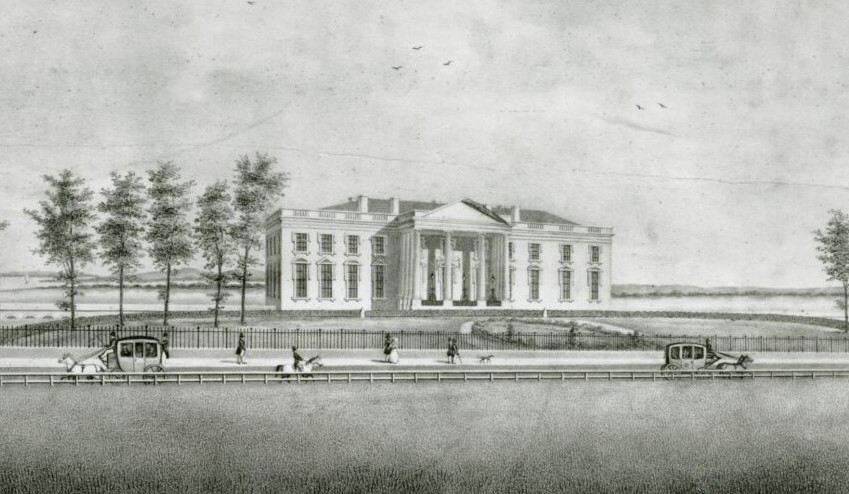

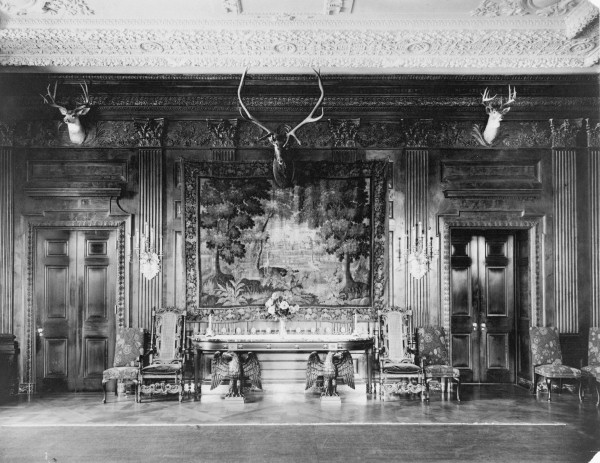

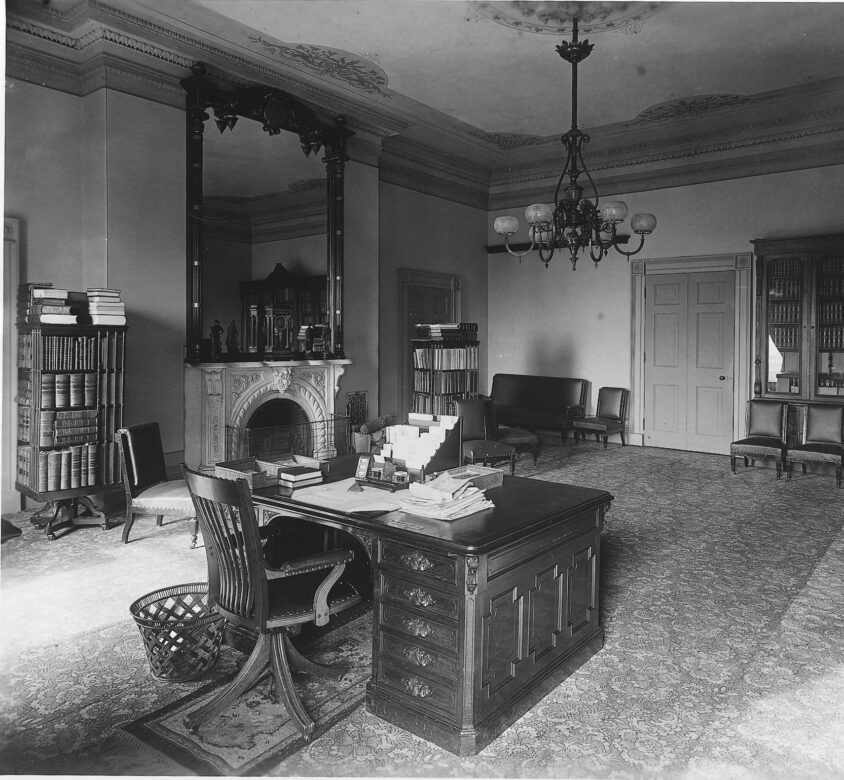

Arthur's Redecoration

President Chester Arthur, known for his refined tastes, undertook a lavish redecoration of the White House interior in 1881–1883, hiring designer Louis Comfort Tiffany to transform its public rooms. Tiffany introduced vibrant colors, ornate furnishings, and stained-glass screens, replacing the outdated and worn decor of previous decades with a high Victorian aesthetic.

Arthur’s redecoration was met with mixed reactions. The New York Times praised the aesthetic improvements but criticized the $110,000 cost (nearly $3,500,000 today), calling it extravagant for a public building; indeed, it was the largest cost spent on the White House since its reconstruction after the War of 1812. Critics in the press, including Harper’s Weekly, accused Arthur of turning the White House into a “palace” unfit for a democratic leader. In Congress, Democrats decried the expenditure as wasteful, especially given Arthur’s reputation as a political machine insider. The Tiffany decorations were later removed or modified by subsequent presidencies, reflecting shifting tastes, but the controversy highlighted the tension between modernization and fiscal restraint.

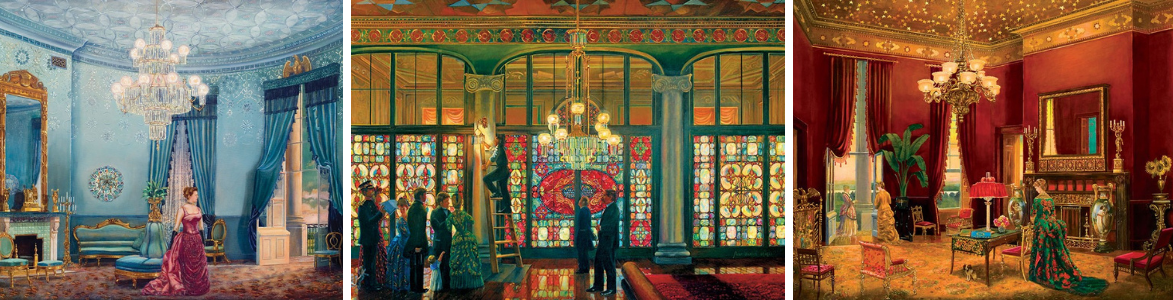

Theodore Roosevelt's West Wing

Theodore Roosevelt’s energetic presidency brought significant changes to the White House in 1902. He oversaw the removal of the Victorian-era conservatories to the west of the White House residence — glasshouses used for growing plants — and replaced them with what we now call the West Wing, a dedicated space for the president and key staff offices. Architect Charles McKim’s design separated the president’s private residence from the growing administrative functions of the presidency.

The demolition of the conservatories sparked outrage among preservationists and horticultural enthusiasts. The Washington Post lamented how Roosevelt’s “attempt to ‘modernize’ [the White House] has destroyed its historic value and does not seem to have made it much more desirable as a residence.”

Critics argued that Roosevelt’s modernization prioritized utility over historical charm. In Congress, the $65,000 cost (roughly $2 million today) drew scrutiny, with some lawmakers questioning the need for a new office wing when existing spaces sufficed. Despite the criticism, the West Wing’s functionality proved its worth, accommodating the expanding demands of the executive branch, and eventually having its own television series.

FDR's East Wing

During Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, the White House saw the addition of the East Wing in 1942 to house additional staff and offices, reflecting the growing complexity of the federal government during World War II. The East Wing over time provided space for the first lady’s staff and social functions, including a shelter for wartime security.

The East Wing’s construction was highly controversial due to its timing during wartime. Congressional Republicans labeled the expenditure as wasteful, with some accusing Roosevelt of using the project to bolster his presidency’s image. The secretive nature of the construction, tied to military purposes, further fueled suspicions. However, the East Wing’s utility in supporting the modern presidency eventually quieted critics.

Truman's Major Renovations

Perhaps the most significant renovation in White House history occurred under President Harry Truman, when structural deficiencies necessitated a complete gutting of the interior from 1948 to 1952. Engineers discovered that the White House was in danger of collapse due to weakened wooden beams, outdated plumbing, and electrical systems. The $5.7 million project (approximately $60 million today) involved dismantling the interior, preserving only the outer walls, and rebuilding with modern materials, including steel and concrete.

The scale of the Truman renovation shocked the public and drew intense scrutiny. Preservationists mourned the loss of original interiors, while media outlets questioned the project’s cost during post-war economic recovery.

In Congress, Republicans accused Truman of mismanaging funds, with some suggesting less invasive repairs could have sufficed. The Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion faced pressure to balance modernization with preservation, leading to debates over details like the reuse of historic woodwork. Despite the controversy, the renovation ensured the White House’s structural integrity, allowing it to serve future generations.

In addition to the gutting, Truman proposed adding a balcony to the second floor of the South Portico, now known as the Truman Balcony, to provide the first family with a private outdoor space and enhance the building’s aesthetics.

The Truman Balcony was one of the most contentious of all White House alterations. Architectural purists argued it clashed with the original Palladian style, while Truman’s opponents in Congress, like Representative Frederick A. Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania, accused him of misappropriating the White House for personal indulgence, reminding Congress that “this building belongs to the American people.”

Public opinion was divided, with some appreciating the balcony’s practicality and others viewing its $16,000 cost as a frivolity during economic recovery. Over time, the balcony became an iconic feature, used by first families for relaxation and public appearances.

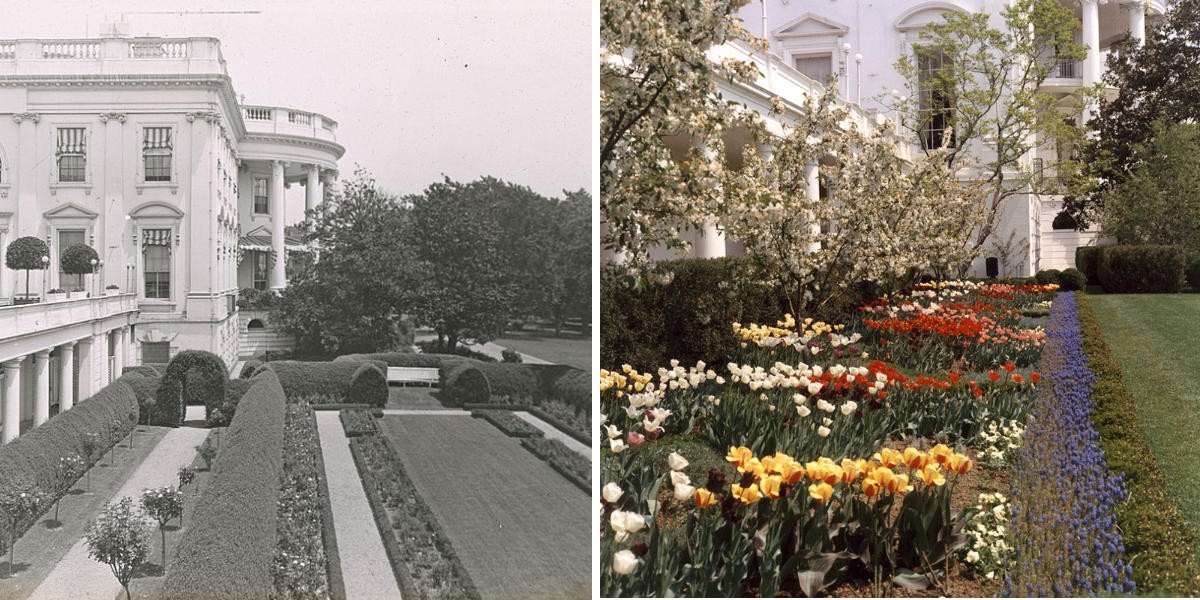

The Kennedy Rose Garden

The White House Rose Garden, redesigned by Jacqueline Kennedy in 1962, has been one of the most iconic outdoor spaces in the White House complex. The site was previously a garden created by Ellen Wilson in 1913, replacing Edith Roosevelt’s 1902 Colonial Garden. Kennedy’s vision, executed by Rachel Lambert Mellon, sought to expand and transform the space into a formal garden fit for official events, inspired by French and English designs.

The Kennedy Rose Garden’s redesign faced criticism at the time. In Congress, some conservative lawmakers viewed Kennedy’s focus on aesthetics as elitist, accusing her of prioritizing style during a time of civil rights tensions and Cold War anxieties. The garden’s elegance and functionality ultimately won over skeptics, cementing its status as a cherished White House feature.

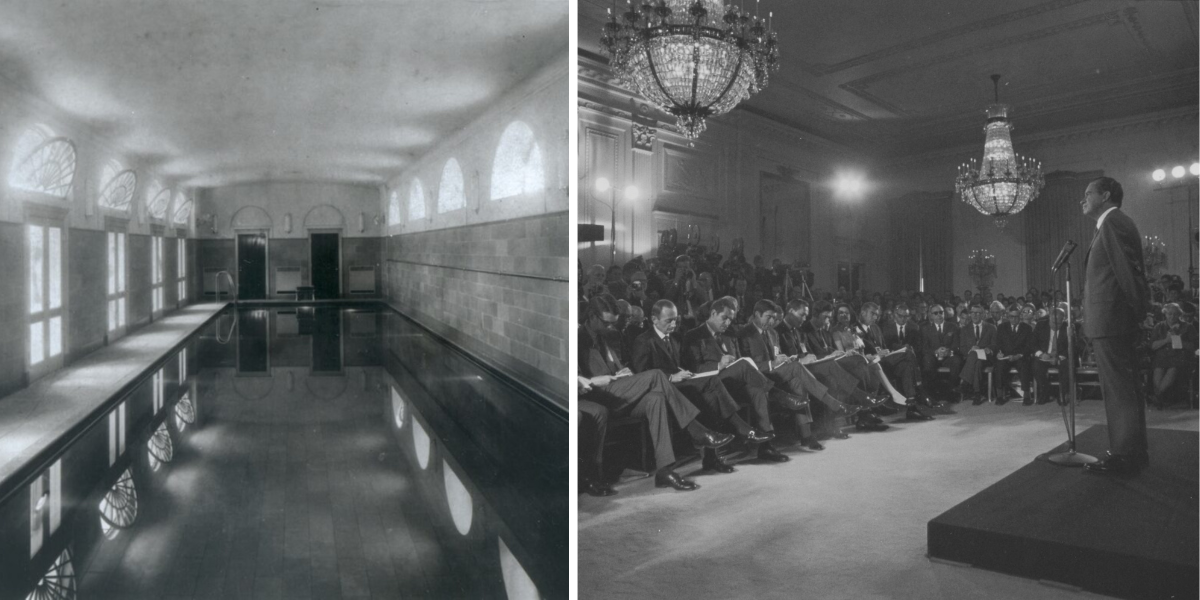

Nixon's Press Room

In 1970, President Richard Nixon converted the White House’s indoor swimming pool, built in 1933 for Franklin Roosevelt’s physical therapy, into today’s James S. Brady Press Briefing Room to accommodate the growing press corps.

The decision to cover the pool was met with dismay by historians and preservationists. The New York Times lamented the loss of a space tied to FDR’s legacy, calling it a “sacrifice of history for convenience.” In Congress, some Democrats accused Nixon of undermining the White House’s heritage to suit his media strategy. The $574,000 cost (over $4 million today) drew scrutiny during economic strain. However, the press corps welcomed the new facility, and the briefing room became a vital hub for White House communications, softening criticism of the conversion over time.

The East Room

The East Room, the largest room in the White House, transitioned from a heavy, dark Victorian decor in the 19th century — featuring ornate chandeliers, dark wallpaper, and heavy draperies — to its current neoclassical elegance. Renovations under Theodore Roosevelt and Jacqueline Kennedy introduced lighter colors, simpler furnishings, and historical authenticity.

Each East Room renovation faced criticism. Theodore Roosevelt’s early 20th-century changes were criticized by preservationists who valued the Victorian charm, with The Evening Star calling them a “loss of grandeur”. When the Kennedys began their 1960s restoration, however, it was this very ‘grandeur’ that critics feared. Congressional debates often centered on funding, with some arguing that private donations should cover aesthetic changes. The East Room’s current design is now admired for its versatility and elegance.

State Dining Room

Theodore Roosevelt’s love for hunting led him to decorate the State Dining Room with taxidermy game heads during his presidency (1901–1909). Subsequent presidencies removed these trophies, transforming the room into a formal space with elegant furnishings and historical portraits.

Roosevelt’s taxidermy was polarizing. The New York Herald described the game heads as “ghastly” and inappropriate for a formal dining space, arguing they clashed with the White House’s dignity. Congressional critics, particularly Democrats, mocked Roosevelt’s decor as a reflection of his outsized personality. The removal of the taxidermy was seen as a return to decorum, though some historians view it as a colorful chapter in White House history.

Lincoln's Bedroom

The Lincoln Bedroom, as it is known today, was Abraham Lincoln’s office and cabinet room during his presidency (1861–1865), not his actual bedroom. It was later converted into a guest room, with its designation solidified in the 20th century to honor Lincoln’s legacy.

The transformation drew criticism from historians who argued it misrepresented history. In the 1950s, The Washington Post questioned the decision to market the room as Lincoln’s bedroom, calling it a “sentimental fiction.” Congressional oversight committees debated the cost of redecorating during the Truman renovation. Despite the controversy, the Lincoln Bedroom remains a powerful symbol, though its historical accuracy is debated.

Pennsylvania Avenue

In 1995, President Bill Clinton closed Pennsylvania Avenue to vehicular traffic in front of the White House, citing security concerns after the Oklahoma City bombing. The Secret Service recommended closure to protect against vehicle-based attacks.

The closure disrupted traffic and public access, drawing criticism from The Washington Times, which called it an overreaction that distanced the “People’s House” from citizens. Local businesses and residents complained about economic impacts. In Congress, Republicans accused Clinton of prioritizing security over openness. The closure remains in place, reflecting the ongoing tension between security and accessibility.

White House Fence

The White House fence evolved from a low, decorative barrier in the 19th century to a taller, more secure structure by the 21st century. Significant height increases occurred after security incidents, with the fence reaching over 13 feet by 2020.

Each height increase sparked debate. The New York Times criticized the taller fences as creating a “fortress-like” appearance, undermining the White House’s symbolic openness. Congressional debates focused on the $64 million cost of the 2020 upgrade. Public reaction on platforms like X framed the changes as responses to specific political climates. Critics argued the higher fence distanced the presidency from the public, while supporters emphasized security needs.

The White House has been shaped by the visions and priorities of its occupants, from Jefferson’s colonnades to Truman’s monumental gutting. Each change—whether Jackson’s North Portico, Arthur’s opulent redecoration, or Clinton’s security measures—has sparked debate, reflecting tensions between preservation and modernization, aesthetics and functionality, and openness and security. Media and Congressional criticisms have often focused on costs, historical integrity, and timing, yet many of these alterations have become integral to the identity of the White House, and it is difficult for us to imagine The White House today without these evolutions and additions. The White House remains a living symbol of American democracy, evolving while enduring as a national landmark.