Abraham Lincoln looked to national laws and the spirit of the Declaration at a time when the Constitution permitted slavery.

-

November/December 2025

Volume70Issue5

Editor’s Note: Dr. Allen C. Guelzo is the Senior Research Scholar in the Council of the Humanities and Director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program at Princeton University. He is the author of several award-winning books on Lincoln, including his most recent, Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment, from which portions of this essay were taken.

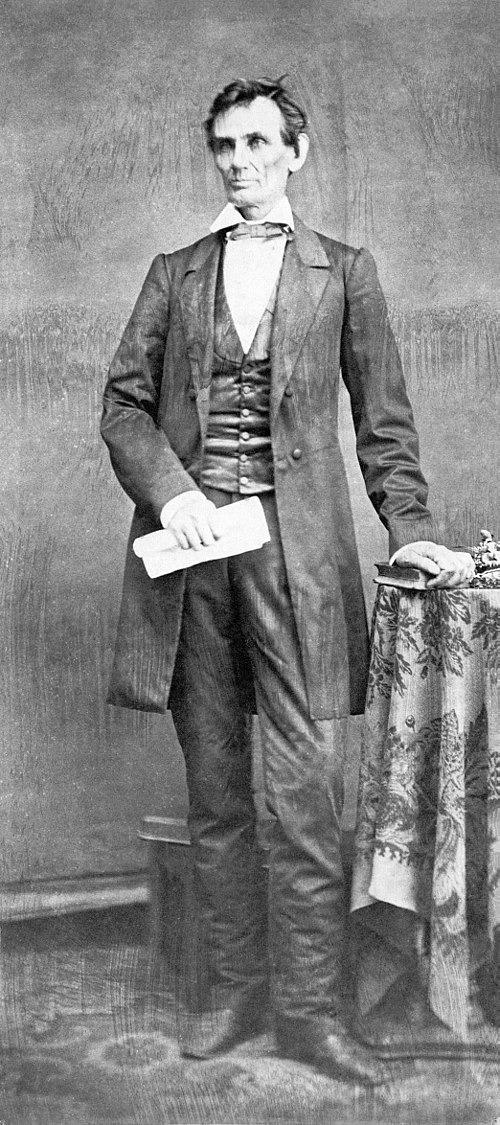

The word “democracy” occurs only 137 times in the collected writings of Abraham Lincoln. But no other word described what he saw as the most natural, the most just, and the most enlightened form of human government. Nothing, he said, could be “as clearly true as the truth of democracy.” And nothing demonstrated that truth more clearly in Lincoln’s mind than the American democracy, which embodied “the great living principle of all Democratic representative government.”

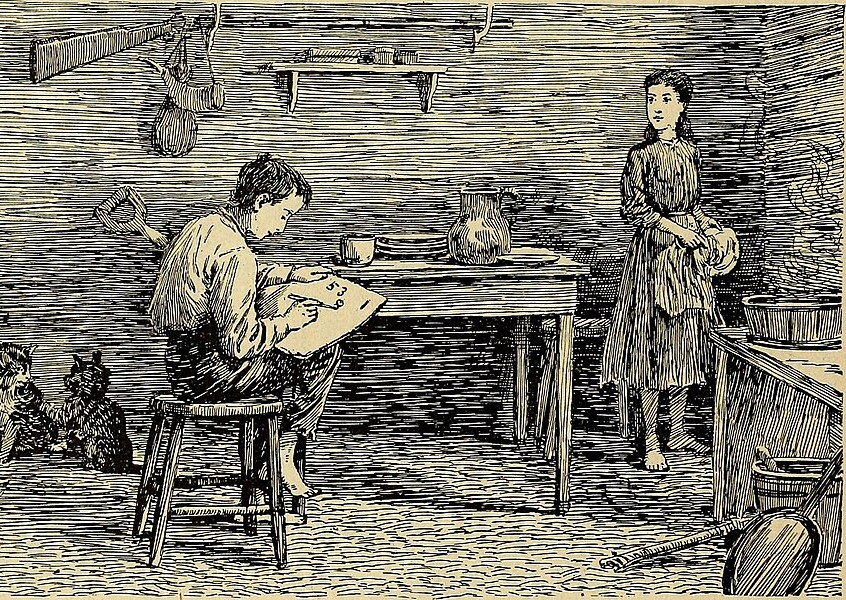

Lincoln’s confidence in democracy was based on three evidences, beginning in the plainest terms with what it had done for him. His own experience illustrated how the absence of a permanent hierarchy in American life permitted anyone to transform themselves. “The principle of ‘Liberty to all’“ was “the principle that clears the path for all – gives hope to all – and, by consequence, enterprize, and industry to all.” As soon as he had entered into adulthood, he was intent on taking that path and “cutting entirely adrift from the old life” he had known on his father’s farm. He was “not ashamed to confess” in 1860 “that twenty-five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat boat – just what might happen to any poor man’s son.”

Not ashamed, because in America, there were no artificial restraints of class, birth, or hierarchy: “every man can make himself.” Lincoln had been “a strange, friendless, uneducated, penniless boy,” but in the democratic air of America, “the prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him.” He can even aspire to the highest office of that democracy. “I happen temporarily to occupy this big White House,” he told an Ohio regiment that he reviewed outside the Executive Mansion in August 1864 – I am a living witness that any one of your children may look to come here as my father’s child has. It is in order that each of you may have through this free government which we have enjoyed, an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence; that you may all have equal privileges in the race of life, with all its desirable human aspirations. In a world still teeming with aristocracies and dictatorships, “such a race of prosperity has been run nowhere else.”

Self-transformation might serve for Lincoln as a justification for democracy, but for others, democracy needed a more transcendent rationale, and that was what Lincoln found in natural law. Modern jurisprudence has relegated much of natural law to the historical attic, but in Lincoln’s day, it remained a potent intellectual resource and has undergone a significant revival among political theorists in our own. Natural law proceeded easily from the assumption, fostered mutually by the Enlightenment, Christian scholasticism, and classical philosophy, that if the physical universe functioned by natural physical laws, then the moral world should reveal similar evidence of law-likeness. “Every law” – meaning physical law – “is found to be in harmony with every other law,” by analogy, in the moral realm, reasoned Francis Wayland (whose works Lincoln “ate up, digested, and assimilated”). Moral codes, and then positive law, form themselves around natural moral law as readily as physics forms itself around natural physical law.

From natural law, it would be possible by “the light of reason” to discern a number of natural rights, or goods, and the Declaration of Independence taught Lincoln that “among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” The “love of liberty,” for instance, is an instinct “which God has planted in our bosoms,” and it is a love which is “the heritage of all men, in all lands, every where.” It was so much a matter of nature that even “the ant, who has toiled and dragged a crumb to his nest, will furiously defend the fruit of his labor, against whatever robber assails him.” In the same way, “the most dumb and stupid slave that ever toiled for a mas ter, does constantly know that he is wronged.” Each of these natural goods is a “right within itself,” and moral uprightness requires that they receive “the protection of all law and all good citizens” for human flourishing.

But the enjoyment of these rights could only exist fully within a democratic framework of self-government. Natural rights were “a standard maxim for a free society, which could be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for.” In turn, they rendered “the doctrine of self-government ... right – absolutely and eternally right.”

It was not always clear whether these rights were an imperative or simply a natural regularity. Either way, there could be “no just rule other than that of moral and abstract Right,” and that “rule” began with “the right of a people to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’“ Those “maxims” also rendered slavery morally wrong-not merely inconvenient and certainly not a “positive good,” but wrong – since “there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.” Was not the Declaration’s assertion of the “equality of natural rights among all nations ... correct”? And “have not all civilized nations, our own among them, made the Slave trade capital, and classed it with piracy and murder? Is it not held to be the great wrong of the world?” It was a loathing so fundamental that Lincoln could not “remember when I did not so think, and feel.”

Finally, democracy shone for Lincoln because it had the sanction of both the American past and the American future. It almost rings naive, in our weary ears, to hear the abolitionist Wendell Phillips announce in 1864 that “the future and inevitable form of all governments is to be democratic; and that all progress tends toward that final and happy goal.” And yet Lincoln was similarly confident democracy would not only triumph in his time but provide a “vast future” for generations to follow. “The popular principle applied to government,” he told Congress in December 1861, has produced everything “which men deem desirable,” and will continue to do so “if firmly maintained ... for the future.” Americans must “diligently apply the means,” he wrote in 1863, “never doubting that a just God, in his own good time, will give us the rightful result.” But that result, if achieved, would “we hope and believe ... liberate the world.”

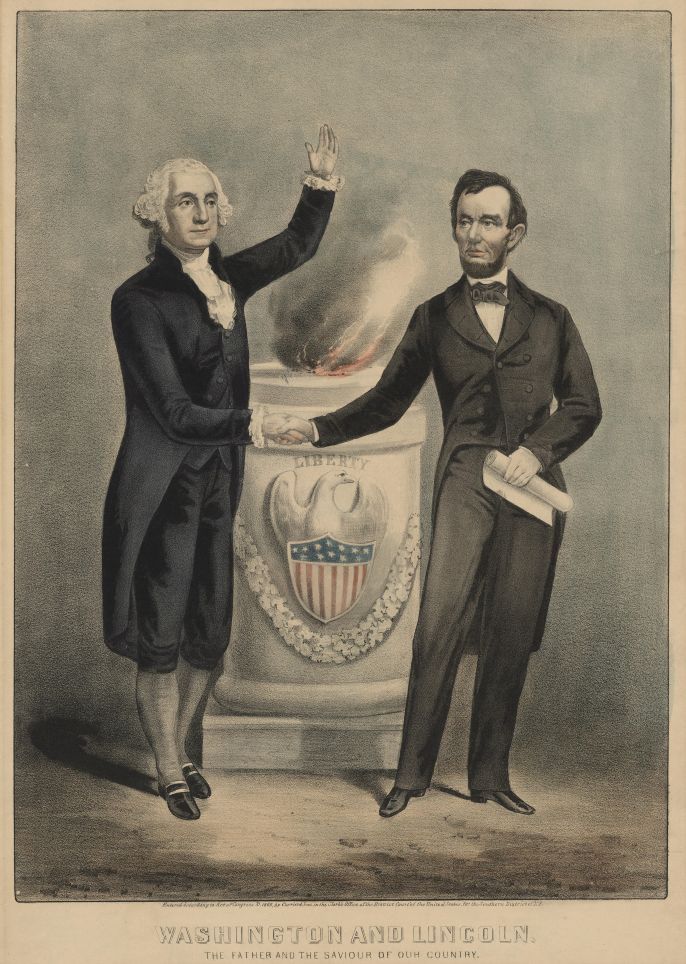

But just as powerful was the vindication given to democracy by the American past. Lincoln inherited from eighteenth century politics the sense that political orders tend downward, toward decay and degeneration, rather than evolving upwards into something different and improved. The solution was to “recur to first principles,” and especially the principles of the American Revolution (a “resuscitation” which had also been urged by Henry Clay). He “knew the tendency of prosperity to breed tyrants,” and so “when in the distant future some man, some faction, some interest, should set up the doctrine that none but rich men, or none but white men, were entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, their posterity might look up again to the Declaration of Independence and take courage to renew the battle which their fathers began.”

In Lincoln’s imagination, the Revolution had been more than merely a domestic rebellion against British taxing authority. He could remember from his boyhood reading of the Revolution’s history that “there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for.” Why else would the revolutionaries have fought so tenaciously? What Americans must do in this new age, he reasoned, is to “re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it.” If “you have been inclined to believe that all men are not created equal in those inalienable rights enumerated by our charter of liberty, let me entreat you to ... return to the fountain whose waters spring close by the blood of the Revolution.”

The Founders “could not have consented that these institutions shall perish; much less could he, in betrayal of so vast, and so sacred a trust, as these free people had confided to him.” He might be living in a different century, but he would be the exponent of “those noble fathers – Washington, Jefferson and Madison.” Democracy was “my ancient faith,” and Lincoln’s certainty of its triumph rose to the level of serenity.

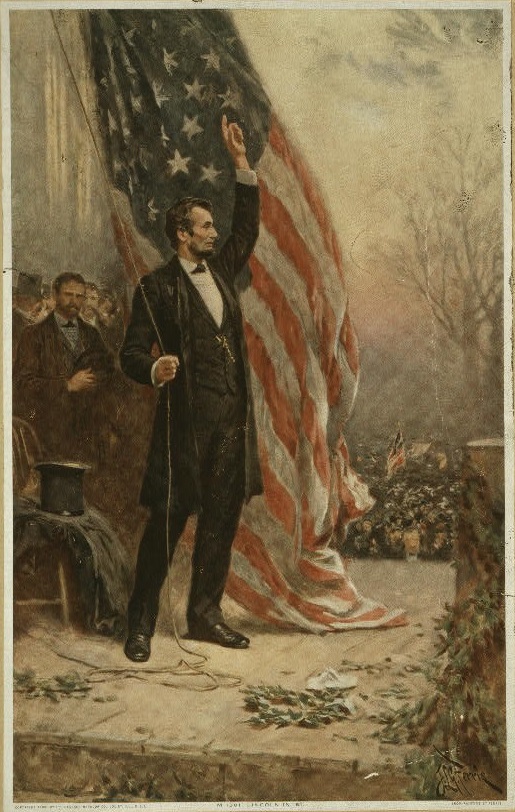

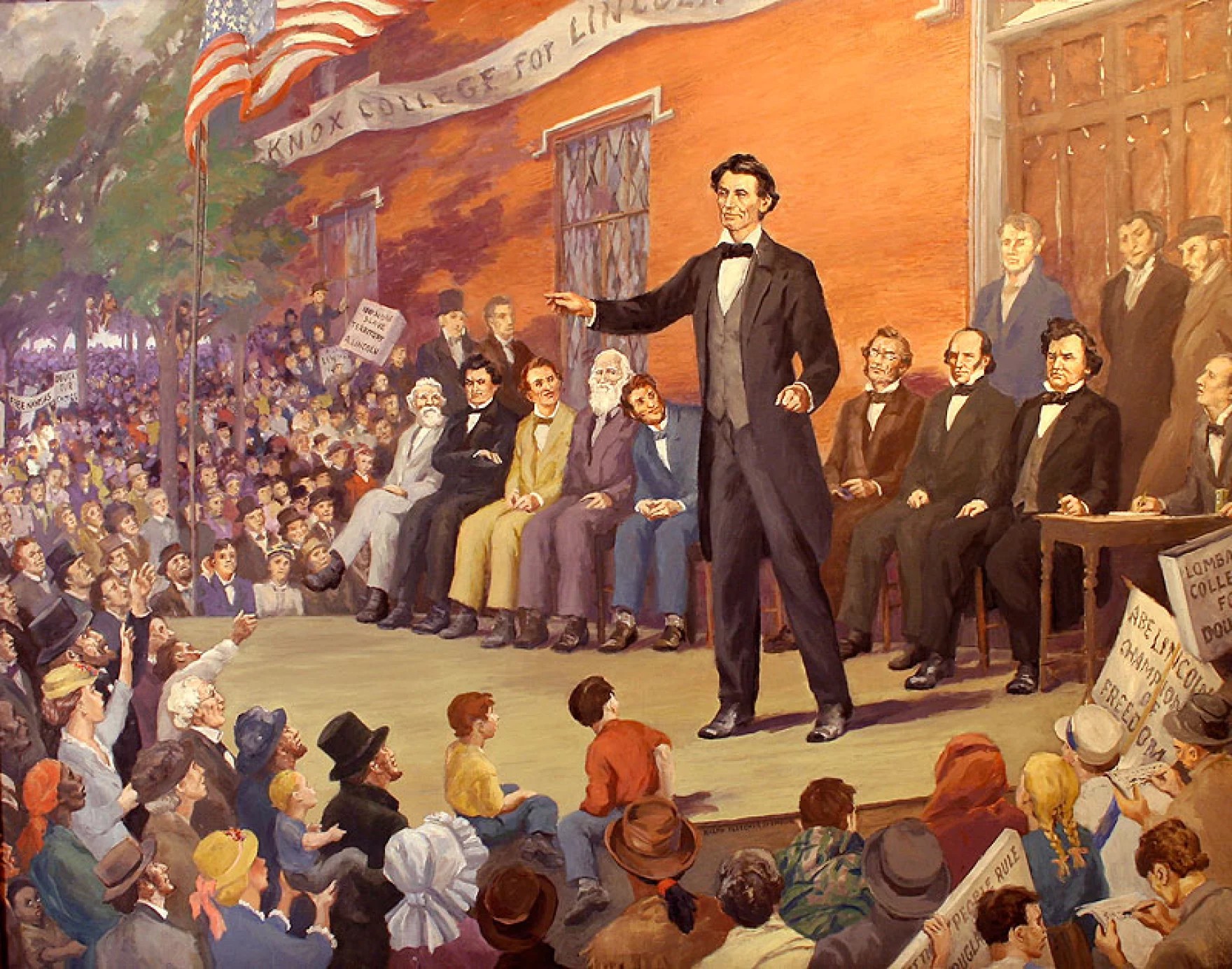

Lincoln did not merely espouse democracy; he looked like democracy. He was as common-looking and homely as a democratic people were themselves common and homely. Henry Clay Whitney, hearing Lincoln speak at Urbana, Illinois, in 1854, thought “he had the appearance of a rough, intelligent farmer.” He was “Stoop Shouldered,” long-armed, with “large and bony” hands, and an attender of the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858 found “his general appearance any thing but prepossessing” (and “his phiz is truly awful”). Above all, he was “not stiff’’ or formal. Jane Martin Johns described him in 1849 as “unaffected, unostentatious,” and Whitney was impressed by how “he entered into conversation in a frank, genial, unconstrained manner as if the stranger was on terms of familiarity and mutual accord, and had been for years.”

Even after his election as president in 1860, Ada Bailhache could spend “an evening at Mr. Lincolns” before his departure from his home in Illinois, scarcely realizing “that I was sitting in the august presence of a real live President.” William Howard Russell, The Times of London’s reporter in America in 1861, was startled to find that at Lincoln’s White House receptions “any one could walk in who chose.” Even the hat he wore en route to Washington and his inauguration sent a democratic message: it was a “soft wool hat” with a wide brim and tall crown, known as a “Kossuth hat,” from the style worn by the Hungarian revolutionary, Lajos Kossuth.

Lincoln did not, however, offer a specific, or even lengthy, definition of democracy, or “representative” democracy, or “a representative Republic,” or a “constitutional republic, or “a democracy – a government of the people, by the same people.” A republic was clearly a democratic space, since its opposite was the suppression of “meetings,” and through that, “to shut men’s mouths,” and he had no hesitation in jumbling together republic and democracy as though they were synonyms. But Lincoln’s only attempt at actually defining democracy occurred, almost in passing, in a note he jotted on the eve of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and at that moment, it was more of an effort to set democracy apart from slavery: “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”

This is a peculiar definition, since Lincoln makes no formal attempt in it at specifying the components of democracy (like the location of sovereignty), and makes no allusion to elections, or even to majority rule. What Lincoln did instead was to draw a contrast between slavery and democracy, so as to illustrate what democracy was not, and that contrast hinged on the point of consent. A slave is someone who has no autonomy, no say in their status, whose consent is unsolicited and undesired, and with no prospect of being delivered from that status.

Consent was a key concept for Lincoln in considering both democracy and slavery. Consent was how sovereignty was exercised: his objection, in 1848, to war with Mexico over the disputed region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande was based on whether the people in that region had ever “submitted themselves to the government or laws of Texas, or of the United States, by consent.” And consent was what drew a line of separation between freedom and enslavement. “This is a world of compensations,” Lincoln concluded, “and he who would be no slave, must consent to have no slave.”

“According to our ancient faith,” Lincoln said in 1854, “the just powers of governments are derived from the consent of the governed.” It was one of the Declaration’s foundational arguments that Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, and Lincoln translated that “axiom” to mean “that no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle-the sheet anchor of American republicanism.” Slavery might have some justification if the slave is not a human being, and is incapable of consent. “If he is not a man, why in that case, he who is a man may, as a matter of self-government, do just as he pleases with him.” But a slave, plainly, is “a man.”

So, Lincoln reasoned, “is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself?” When one man “governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man” without that vital element of consent, “that is more than self-government that is despotism.”