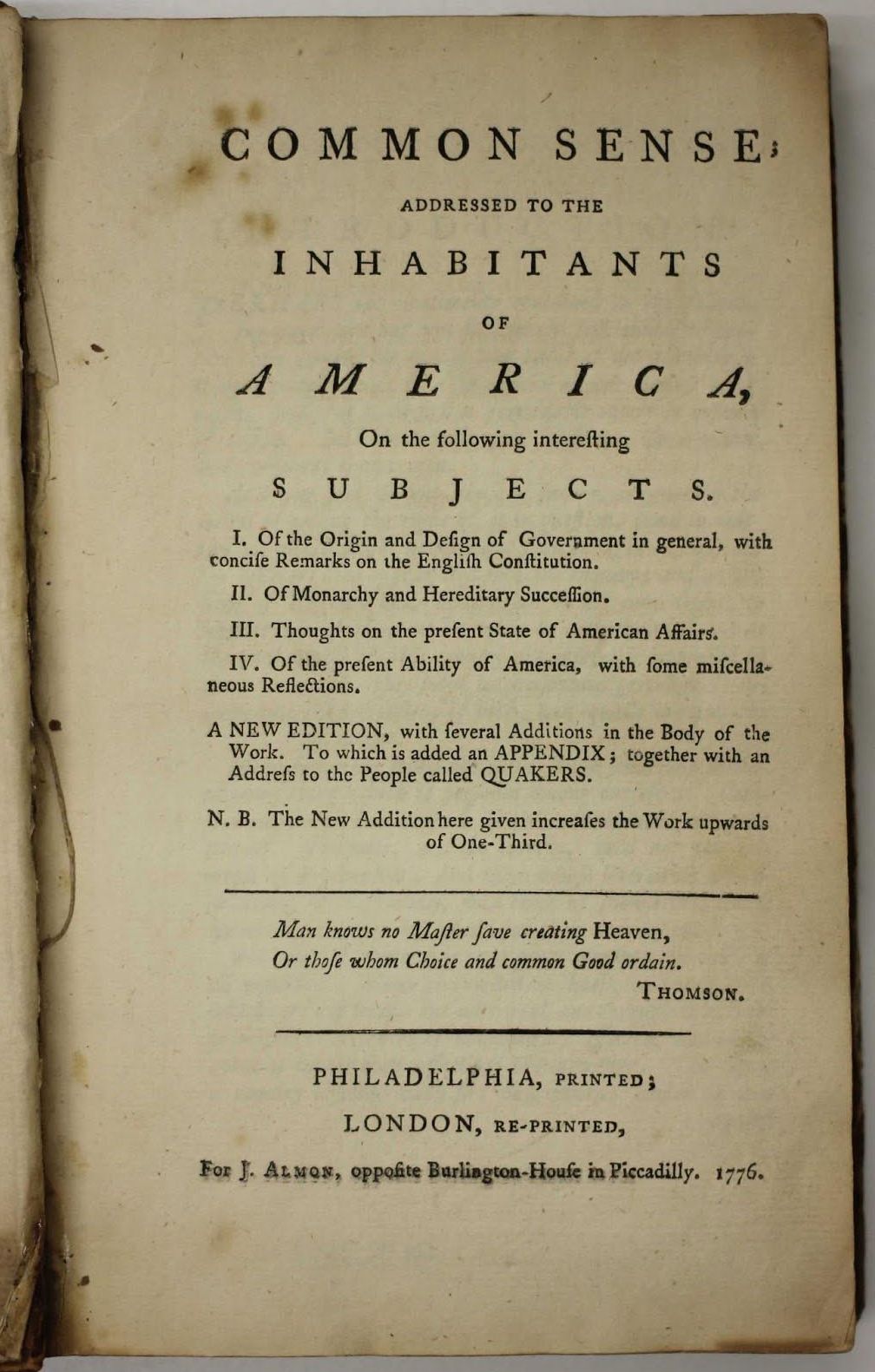

In Common Sense, Paine explained in blunt language why Americans needed a revolution

-

Winter 2026

Volume71Issue1

In the opening months of the Revolutionary War, America’s ragtag militias and jerry-built Continental Army squared off against the most professional army then on the planet. The battles of Lexington and Concord demonstrated that Americans would fight, and fight hard.

Two months later, they won respect at Boston’s battle of Bunker Hill, yielding the battlefield but inflicting punishing casualties that staggered British officers. Thirteen thousand New Englanders raced to surround Boston and seal off the enemy forces from the rest of North America. The Royal Navy would be forced to evacuate those troops.

But British power soon took its toll. A multi-pronged American invasion of Canada ended ignominiously. Some Americans wavered, uncertain whether their goal should be independence, or simply winning greater respect from British officialdom, or peace at any price. At the end of the year, a pamphlet by a recent immigrant from England brought focus to that choice, persuading great swaths of colonials that only independence would do.

In 1775, few thought thirty-eight-year-old Thomas Paine was on the cusp of great achievement. The son of an Anglican mother and a Quaker father, he knew only a few years of schooling. His first wife died in childbirth. A second, childless marriage dissolved. He sailed for a few months on a privateer in the English Channel, occasionally taught school, and unsuccessfully took up his father’s trade as a maker of stays for ladies’ corsets, instruments of quiet torture designed to shape female bodies to hourglass proportions.

Paine became one of the King’s tax collectors, an occupation often despised on both sides of the Atlantic.. Twice discharged from the tax service – once for unexplained absences, once for apparent irregularities – he petitioned the British government for improved pay and conditions for collectors. His petitions didn’t succeed, though he fell in with English radicals who questioned the Royal government.

When Paine sought out Benjamin Franklin in London in 1774, the American sage suggested crossing the Atlantic to America. The former collector soon would become the voice of America’s founding tax rebellion.

In the New World, Paine found work as a writer and editor in Pennsylvania. Sensing that America’s revolutionary ardor might wane, Paine recognized that the rebellious colonies faced a momentous choice. Did they simply want lower taxes? Or perhaps to win a colonial legislative body that would be subordinate to Parliament in London, while remaining within the British Empire? Or should they aim higher? The unknown scribbler chose the most audacious goal, rallying American spirits by explaining that they must oppose monarchy and repression.

In the most popular version of Common Sense, Paine opened with a soaring appeal for Americans to remake their world: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation similar to the present hath not happened since the days of Noah . . The birth-day of a new world is at hand.”

Paine mounted a frontal attack on monarchy in general, and on King George III in particular. Why, Paine asked, give power to a man whose subjects boasted that the House of Lords and House of Commons checked his will, which could only mean that “the people are afraid to trust [him] and always obliged to check [him]”?

The Bible, Paine added, described numerous incompetent kings, contradicting any suggestion that kings have extraordinary gifts, or rule by divine right. If the Bible told of foolish kings, there could be no error in finding later kings to be fools. Paine scorned hereditary monarchy as “a degradation and lessening of ourselves [and] an insult and an imposition on posterity.”

Paine’s aim was to demonstrate that every emperor (or king) wore no clothes. He dismissed the first king of any dynasty as “the principal ruffian of some restless gang whose savage manners. . . obtained him the title of chief among plunderers.” That thug’s descendants, Paine continued, would lack even those brutal gifts. Kings, he warned, “soon grow insolent” and “are frequently the most ignorant and unfit.” He pointed out that across seven centuries since the Norman Conquest in 1066, Britain had endured “no less than eight civil wars and nineteen rebellions.” What was the virtue of a form of government that inflicted such horrors on its people?

Having dismantled the idea of monarchy, Paine turned to George III personally. Reciting the king’s recent speech on the American crisis, Paine insisted that “Brutality and tyranny appear on the face of it.” The king, he insisted, had violated “every moral and human obligation, trampled nature and conscience beneath his feet; and by a steady and constitutional spirit of insolence and cruelty, procured for himself a universal hatred.”

Sounding themes that would echo through the Founding Era, Common Sense complained that Britain had dragged Americans into its wars with European rivals, ruining American trade. Only with independence could America avoid Britain’s wars.

Paine stated powerfully the differences between the British monarchy and the spirit of the American rebellion. “[I]n absolute governments the King is law, [but] in free countries the law ought to be king, and there ought to be no other.”

He saw a unique opportunity before his adopted countrymen:

The power of Common Sense came from its ideas, its use of the blunt, everyday language of taverns and street corners, its scorn for the flowery language of the eighteenth-century literati. It was lively. Most pages contain a sentence that demands to be read aloud and savored. Paine wrote with urgency, figuratively gripping the reader’s lapel with one hand and wagging a finger with the other.

The spread of Common Sense was viral two centuries before that term became viral. A population of roughly three million Americans purchased at least 150,000 copies..

Along with its sales figures came its explosive political impact. For Americans uncertain why they should fight Britain, Paine ripped aside the curtain that cloaked the unsavory features of British rule and its monarch, revealing them as contemptible, greedy, and unworthy of loyalty. Patrick Henry had told Americans that they must fight, demanding for himself liberty or death. Paine explained why they must fight.

Six months after Common Sense first appeared, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia rose in the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. His resolution stated that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States . . . absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown,” with “all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain . . . dissolved.”

A month later, Congress approved his resolution.