“It is recommended,” proclaimed Lincoln, that the people “celebrate the anniversary of the birthday of the Father of his Country."

-

Winter 2019

Volume64Issue1

On February 19, 1862, with armies drilling for the spring Civil War campaigning season, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation. “It is recommended,” he wrote, “to the People of the United States that they assemble in their customary places for public solemnities on the twenty-second day of February instant, and celebrate the anniversary of the Birthday of the Father of his Country, by causing to be read to them his immortal Farewell address.” That was all.

Lincoln didn’t say anything about “sale-a-brations” or “Buy George” savings on dinette sets. He certainly didn’t realize that through the years his original concept of a near sacred holiday for the reading of Washington’s most succinct manifesto would blur into a meaningless thing, a Monday without mail called Presidents Day.

George Washington’s life did have meaning for Lincoln. While the sixteenth President may have had other, more direct political role models, such as Henry Clay and Zachary Taylor, Washington was an idol who loomed on all levels. One day in Springfield a bunch of friends just shooting the bull settled on the topic of the first President and inconsistencies in his character. Lincoln turned the conversation back before it even started. “Let us believe,” he said, “as in the days of our youth, that Washington was spotless. It makes human nature better to believe that one human being was perfect—that human perfection is possible.”

If that smacks of religious fervor and a compelling need for faith, it is probably because Lincoln’s attitude toward the nation and the community of belief that sustained it did rise to the level of a political religion, as he once termed it. The public didn’t greet the notion of a political religion with much excitement, though, and so Lincoln stopped trying to explain it early on. But he continued to live it.

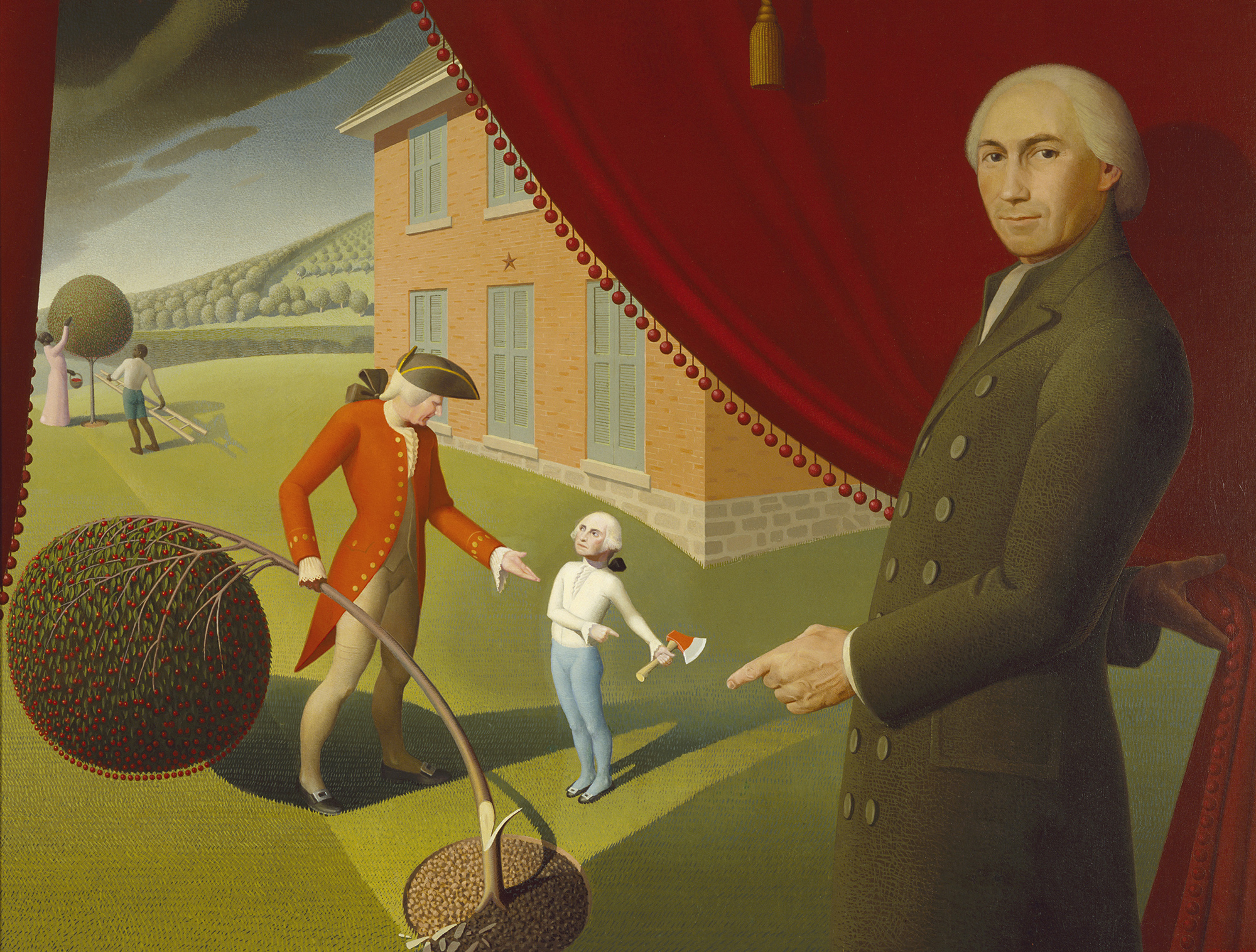

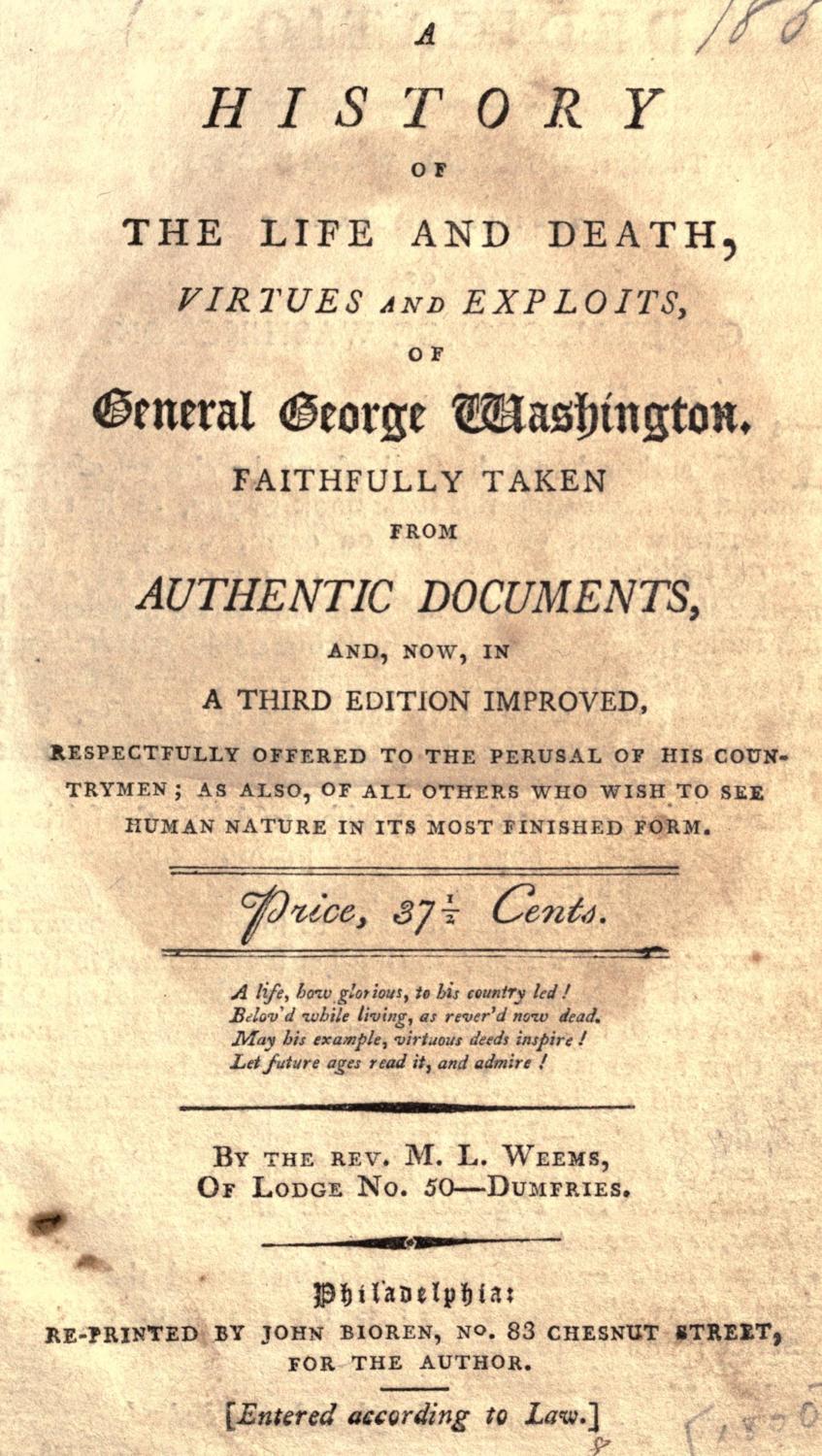

Two of the books that Lincoln is known to have read as a boy were biographies of George Washington. One, by Parson Weems, stressed a fact that has long since become a cliché: that if a boy is honest, virtuous, and hard-working, as George Washington was, then he will almost certainly succeed in the America that Washington left behind. Like all clichés, it has a strain of truth in it, and never more than in the case of Abraham Lincoln. He was honest and he was virtuous. He was also hard-working, at least sometimes. All of those traits must have been part of him through breeding or upbringing, but the specter of Washington may have served to hold him to the highest standard even in the tightest squeezes, as the example of an idol can do.

The Weems biography was also influential for Lincoln in its emphasis on Washington’s Farewell Address. That was a speech that remained paramount in Lincoln’s thinking both as an interpretation of the documents that formed the nation and as a set of directives based (unlike those documents) on actual experience.

As a politician in the mid-nineteenth century, Lincoln was always happy to have himself associated with Washington, and he often made reference to the first President. When someone mentioned in passing that Washington was a first-rate wrestler in his early days, Lincoln leapt into the conversation. “It is rather a curious thing,” he boasted, “but that is exactly my record. I could outlift any man in southern Illinois when I was young, and I never was thrown. . . . If George was loafing around here now, I should be glad to have a tussle with him, and I rather believe that one of the plain people of Illinois would be able to manage the aristocrat of old Virginia.”

When the company wasn’t too polite, Lincoln liked to repeat a story that was likewise drenched in hero worship. After the Revolutionary War, Ethan Allen visited England and reported that in hopes of tweaking visiting Americans, his hosts had hung a picture of George Washington in the back house, as Lincoln called an outhouse. Colonel Allen, according to Lincoln’s telling, was not annoyed in the least, pronouncing the back house the very perfect place for the portrait, since “there is nothing that makes an Englishman s--- faster than the sight of General Washington.”

Washington’s Farewell Address, delivered on September 19, 1796, and directed to his fellow American citizens, is best-known for its admonition to avoid entanglements with foreign nations. Another part of the speech, however, contained Washington’s foreboding about the future of the states and their adhesion to the concept of the federal government. Calling the “unity of government” a pillar in the edifice of independence, Washington said “it is easy to foresee, that from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth.”

He may well have been speaking of the differing regional views of slavery. Washington said elsewhere that “I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union.” That job, the rooting out of slavery, as well as of course the preservation of the unity of government, was left to the willing inheritor of Washington’s directive, Abraham Lincoln.

Where Washington was the acknowledged leader of eight or ten truly brilliant Americans in the formation of the country, Lincoln was strangely alone three generations later, when the Founders’ legacy reached the brink of disintegration. They were the Founding Fathers. He was just Abraham Lincoln of Illinois.

As he left Springfield for the capital and his first inauguration, with Southern states already planning secession and assassins plotting, Lincoln made a few impromptu remarks at the train station. “To-day I leave you,” he said to those gathered to say good-bye, “I go to assume a task more difficult than that which devolved upon General Washington. Unless the great God who assisted him, shall be with and aid me, I must fail. But if the same omniscient mind, and the same Almighty arm that directed and protected him, shall guide and support me, I shall not fail.”

Washington would have appreciated Lincoln as well, we can guess, though perhaps not with quite the same intensity. When Lincoln was alone, he had, at least, Washington. George Washington, for his part, was never alone, but the evidence suggests he would have respected Lincoln’s renewal of the unity of government and the fact that he purged the country, once and for all, of slavery.

But he wouldn’t have liked those off-color stories, even if he was the beneficiary of the belly laugh.