Ambitious, temperamental, and passionate, George Washington learned the skills in the French and Indian War that laid the groundwork for the great leader that he would become.

-

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books

Volume64Issue5

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Young Washington: How Wilderness and War Forged America's Founding Father, by Peter Stark (Ecco)

The tired, sodden travelers rode into the old Indian town of Venango at the mouth of Rivière Le Boeuf.

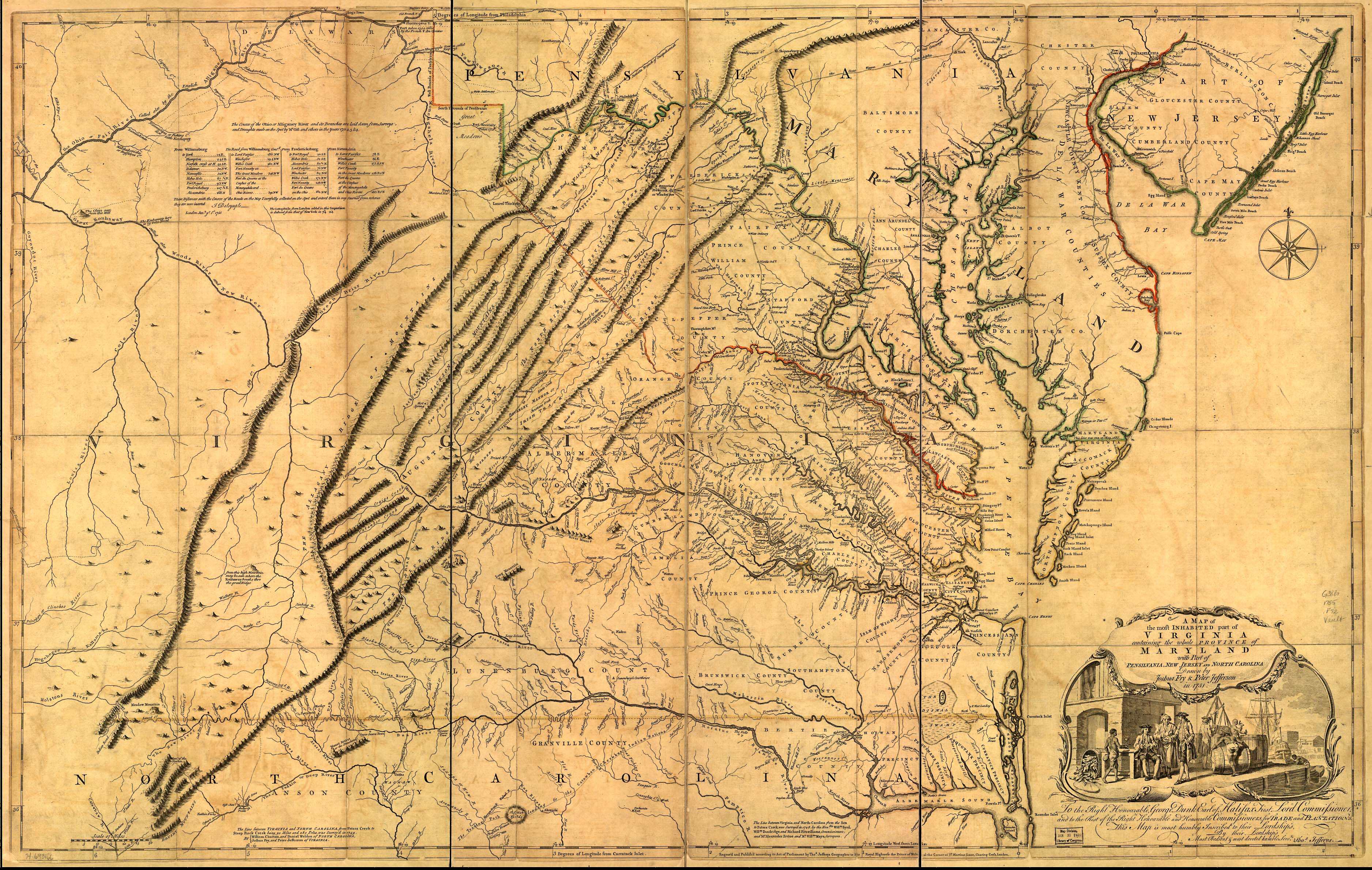

Twenty-one-year-old George Washington had never traveled this deep into the wilds. He had now ridden nearly five hundred miles from the elegant plantations of coastal Virginia, over the crest of the Appalachians, far into the Ohio Valley wilderness, a great forest in America's interior approximately the size of Spain. Smoke plumed from bark-covered longhouses and hung low in the damp, rainy air.

It was early December 1753. A deep chill wrapped the forest clearing. Children and scrawny dogs ran on muddy paths. The arrival of the little caravan—the tall young stranger who carried himself with a proud bearing, the shaggy frontiersman guide, the French-speaking interpreter, the hired men handling the packhorses, the three Indian chiefs—brought out onlookers as word spread among the longhouses. The youthful white planter from the distant Atlantic coast of British America self-consciously rode through the native village, anxious to carry out this crucial step in his first mission for Virginia's Governor Dinwiddie—to deliver a message to the French commandant somewhere in the Ohio wilderness.

A stouter log cabin squatted amid the bark longhouses, a geometric cube intruding on an organic world. The French flag draped limply from a pole. The cabin had served as the trading post of British subject John Fraser until the French had recently evicted him. This, too, informed Washington's mission—to learn why the French had so boldly removed British colonist and trader Fraser from the Indian village of Venango and occupied his post.

Washington headed directly for the former trading post, now under the French flag, accompanied by his frontiersman guide, Christopher Gist, and his interpreter for French, Jacob van Braam. Three French military officers received him with formal introductions and polite respect. Captain Phillipe Thomas Joncaire stepped forward as the ranking officer. Son of a French trader and Seneca mother, 46-year-old Captain Joncaire had lived in the interior wilds since the age of eleven. Known to the Indians as Nitachinon, he had great influence among the tribes of the region, moving easily between the two worlds and working diplomatically to ally them to the French. Amid the fluid French graciousness, Washington abruptly asked who was the commander of French forces in the Ohio Valley.

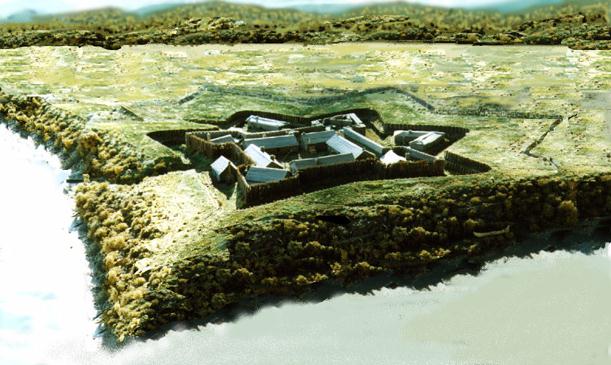

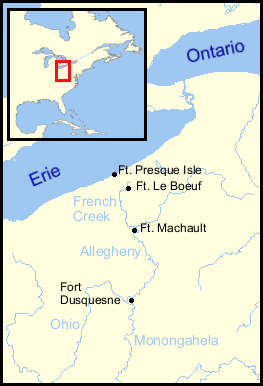

Captain Joncaire politely replied that while he had command of the Ohio, another officer, Saint-Pierre, ranked higher. Washington should deliver to Saint-Pierre the letter from the governor of Virginia that he carried in his satchel. He could be found at the headwaters of Rivière Le Boeuf—River of the Buffalo—where the French had recently erected a fortification.

How far away?

Several days' ride, he was told.

The veteran Captain Joncaire had more or less brushed Washington off. Anticipating a formal encounter after his long journey into the Ohio wilderness, Washington may have felt belittled by Joncaire's dismissal. He surely felt intimidated by the wilderness veteran and military officer twenty-five years his senior, and perhaps angered that he wasn't being taken seriously enough.

George Washington at twenty-one was a very different Washington from the one we know and hold sacred, different from the stately commander of the Continental Army, the selfless first president, the unblemished father of our country gazing off into posterity. This is not the Washington possessed of nearly superhuman virtue, who, given the chance to consolidate power and rule indefinitely over the just-born nation, willingly stepped down and returned to a quiet life on his Virginia plantation. Rather, this is the young Washington. But not the Washington of the cherry-tree bedtime story. This young Washington is ambitious, temperamental, vain, thin-skinned, petulant, awkward, demanding, stubborn, annoying, hasty, passionate. This Washington has not yet learned to cultivate his image or contain his emotions. Here, instead, is a raw young man struggling toward maturity and in love with a close friend's wife. This is the Washington of emotional neediness, personal ambition, and mistakes—many mistakes.

See also "G. Washington Meets a Test," by Thomas Fleming

Everything about Washington's life played out on a grander scale than most people's, including his maturing during his younger years. Most young people make mistakes. Many learn from them. The difference with Washington is that the mistakes he made occurred in an arena that quickly expanded from local, to regional, and finally to global, with far-reaching historical consequences. While the older, mature Washington would lead the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, this young, raw Washington personally bears responsibility for inadvertently striking the spark that lit the tinder that exploded into the French and Indian War. This young Washington was accused of being a war criminal, an assassin, a murderer, an incompetent leader, negligent, and an international embarrassment.

The war that he touched off would last seven years and spread around the world—the first truly global war. Unfamiliar to many Americans, this war in the late 1750s and early 1760s won much of the North American continent for the British. At the same time, it unleashed the forces that twenty years later would mushroom into the American Revolution against those same British. These pivotal early years of Washington's life give us a picture much at odds with his popular image. This war and his personal passage through the wilderness laid the groundwork for the great leader that Washington would one day become.

For over two centuries, adventurous young men had struck out for the wilderness of the New World. They sought their fortunes, they tested themselves. The passage through the wilderness would become a ritual of life in the New World. Some young men set off and never returned. Others struck on great discoveries—gold, fur, ancient civilizations, vast lands. Still others, taken captive, returned with stories to tell about what lay out there. In five crucial years during his early twenties, George Washington traversed between the "civilization" of the Atlantic coast—with its gracious plantations, linen tablecloths, and attentive servants and slaves—and the wilderness of the North American interior that lay over the mountains, a few hundred miles away. These vastly different worlds would mold Washington as he underwent the transition from adolescence to adulthood and moved from self-centered youth to empathetic adult, from ambitious individual to selfless leader.

Washington's passage parallels what in mythology Joseph Campbell calls the "hero's journey." As the hero travels from the known to the unknown world, often a wilderness, he encounters supernatural powers and mythical beasts and undergoes a series of trials. He returns, ultimately, the "master of two worlds." Through this five-year journey from the civilized coast through wilderness and war and the long series of struggles and mistakes that accompanied them, Washington eventually became a master of two worlds. As master of two worlds, and finally as master of himself, George Washington would go on to accomplish extraordinary things.

ON THIS, his first mission as a part-time junior officer in the Virginia militia, eager to make a name and propel himself into the Virginia aristocracy, young Washington felt a surge of anxiety. How much longer to his destination? Governor Dinwiddie had urged him to go with all possible haste, as every delay could be costly. Now Captain Joncaire was telling him he faced several days' additional ride to reach the French commandant who resided upriver at the fort of the buffalo—French Fort Le Boeuf.

Business completed, mission diverted, Captain Joncaire invited Washington, Gist, and van Braam to dine with him and his fellow French officers. The travelers received impeccable hospitality. One can imagine the crude log cabin with a fire blazing in the hearth, candles burning on the table's rough boards. Outside, the light faded quickly in early December and damp twilight dimmed to blackness. But the warmth and guttering light within revealed a table laden with roasted venison, perhaps beaver tail, elk, and other meaty delicacies of the forest, brought in by Indian hunters. The French officers offered the luxury of bread baked with wheat flour, transported by canoe down the Rivière Le Boeuf from French outposts on the Great Lakes, supplied from Montreal. After a four-week journey from the coast, the dinner came as a sumptuous banquet for Washington and his companions.

And the wine flowed, abundantly. The French officers drank, copiously. Washington held back, tracked the conversation, perhaps tried to ask some questions.

On what basis could they claim possession of the Ohio? It was well known that the region fell within the capacious western borders of the British province of Virginia.

France, they told him, claimed the Ohio on the basis of the explorations of La Salle.

Washington did not understand. Amid the wine and the candlelight, they explained that La Salle had explored the great Ohio River valley many decades earlier—at least sixty years ago—and claimed it for France. They had used it for many decades as a route for their fur trade, and now they would occupy it, manning a series of forts under construction on the Great Lakes and along the Ohio and tributaries. The French had heard that settler families from British coastal colonies such as Virginia and Pennsylvania had crossed the Appalachians to clear homesteads in the Ohio Valley. British fur traders already operated in the region. The French forts would halt this British encroachment.

These were strong words. The French had determined to take the Ohio—land that Virginia claimed as its own. With the wine giving "License to their tongues," as Washington, earnestly trying to gather intelligence, put it in his journal, the French officers laid out their strategic thinking. "They were sensible the English could raise two Men for their one; yet they knew [that the English] Motions were too slow and dilatory to prevent any Undertaking of theirs."

The wine flowed. The light flickered on the log walls of the British trader Fraser's former outpost, now occupied by the French. The officers drank. "They told me," Washington recorded, "That it was their absolute Design to take Possession of the Ohio, and by G—they would do it."

HERE, in this wilderness outpost on the Ohio headwaters, over a dinner of wild game, with a determined twenty-one-year-old in attendance, two world empires bumped against each other like great weighty vessels on a rolling sea. For decades France and Britain had regarded each other as bitter rivals. One an island nation, the other locked in a continental mass, they jealously faced each other across a narrow channel of water, each looking for advantage. They fed their growth by acquiring colonies around the globe, their fleets of ships briskly hauling traded goods back and forth between mother country and far-flung colonial outposts, with every shipload—furs, sugar, rum—boosting the royal treasuries.

France had landed her first North American settlers in 1604 at today's Nova Scotia. By sailing ship and birch-bark canoe, she had worked her way up the Saint Lawrence River into the continent's interior, pursuing the trade in furs and befriending the Indian nations among whom the French colonists lived and intermarried. The English established their first colonies to the south, on the Atlantic coast, in 1607 at Jamestown in today's Virginia, and then at Plymouth in today's Massachusetts. They cleared land and planted crops, gradually pushing aside and often warring with the native inhabitants.

At what became Virginia, the earliest colonists had, in effect, planted two flags in the ground along the coast, separated by two hundred miles, and said, We own all the land from here westward to the island of California. Initially believed to be an island, the Pacific coast had been explored in the 1500s by Spanish ships and by Sir Francis Drake. The early British colonists had little idea how far the continent actually extended, or what lay on the far side, and they initially ventured no farther inland from the flat green Atlantic Seaboard than the edge of the Appalachian Mountains.

But now, in the mid-1700s, nearly a century and a half after planting those first flags, after clearing forests and building farms and tobacco plantations manned by African slaves, the British colonists had begun to outgrow that narrow coastal plain. First the settlers bumped up against the Appalachian Mountains. Then the very bravest and most intrepid, crossing on foot and horseback, began to spill over, just a few of them, like trader John Fraser, into the vast wilderness of the Ohio Valley, which British Virginia claimed on the basis of those two flags.

The thousand-mile Ohio River, like a great vein draining the eastern continent, rises near Lake Erie. It flows west and south, fed by countless smaller rivers and streams, until it spreads to nearly a mile in width and pours into the Mississippi River near today's Saint Louis. The French had used the Ohio—the "good river" in the Iroquoian languages, or the "beautiful river"—for decades not only as a trading route but as a link between their Canadian colony to the north and their French colony far down at the mouth of the Mississippi, New Orleans. Plied by voyageur canoes and bateaux—a kind of flat-bottomed cargo canoe—the Ohio River was, as historian Francis Parkman put it, a French line of communication between the snows of Canada and the canebrakes of Louisiana.

Read a review of David McCullough's The Pioneers

For centuries the two powers, France and Britain, had vied for dominance in Europe, most recently in the War of the Austrian Succession. This had lasted nearly a decade and ended only five years earlier, in 1748. At issue, at least to start, was who would inherit the realm of Charles VI of the Habsburgs. France and her allies wanted the realm broken up. Britain and her allies, worried about French dominance on the continent, wanted it to remain intact. Such was the infinitely complex balance of power in Europe, where alliances and treaties blossomed and faded like flowers in spring rains. While the Austrian succession issue was settled in 1748, and a treaty signed, the tensions and rivalry between France and Britain still simmered just beneath the calm surface.

And now the great empires bumped and jostled softly during this polite, wine-soaked evening in a log cabin in the Indian town of Venango. One can picture Washington at the table, quiet, socially awkward, over six feet tall with broad shoulders, a fine rider and good athlete, but lacking a formal education. He knows the French and British have been enemies and are now at peace. He knows that his leader, Governor Dinwiddie, bewigged and jowly, back in the Virginia capital at Williamsburg, has land investments in the Ohio Valley. He knows that he must move quickly, at the governor's orders, to deliver the message to the French commandant. But young Washington cannot conceive of the weight of empires pressing down inside the warm cabin on this cold, damp December evening in the Ohio wilderness.

THE NEXT DAY IT RAINED-HARD. A frustrated Washington, holed up in his tent, with rain pattering on the woven fabric, couldn't travel. Even one day's delay wore on his patience. He had arrived in the wrong place. His mission had been shunted in a new direction by Captain Joncaire. Now rain fell with no end in sight and he would need several days more to deliver the governor's urgent letter.

Other tensions besides Washington's haste hung over the dripping Indian town. Both the French and the British were attempting to win the Indians to their side, working within an intertribal web of relationships as complex as the alliance-bound kingdoms of Europe. Whichever nation, France or Britain, earned the allegiance of the Ohio tribes and the nearby Iroquois would possess a great advantage in laying claim to the vast wilderness. But the tribes did not speak with a single voice. Of the several different tribes at Venango, the Delaware Indians there "lived under the French colors," as frontier guide Gist put it in his journal. The three chiefs traveling with Washington's party—the imposing Iroquois chief known as the Half King, Jesakake, and White Thunder—were partial to the British. They tried to convince the Delaware Indians living under the French flag at Venango to switch allegiances and pledge friendship to the British, too.

They refused to switch.

Washington, meanwhile, struggled to keep "his" Indians—the three chiefs, or sachems—away from Captain Joncaire. He worried that Joncaire would use his clever arts of persuasion to win them to the French side. The first night at dinner, Washington had kept them from coming to the French officers' quarters, out of sight in the Indian town. The next day, when Joncaire realized that the Half King and other sachems had arrived in Venango with Washington's party the day before, he asked Washington why he had not mentioned their presence.

Young Washington told a diplomatic lie. He had heard the captain speak disparagingly of Indians, he said to Joncaire. Having heard the captain speak thus, Washington thought that the captain would not want to see them.

"I excused it in the best Manner I was capable," Washington reported.

Their presence revealed, Captain Joncaire employed all his skill to win over the three chiefs, giving them presents and pouring generous servings of brandy until they had become thoroughly drunk.

By the next day, however, the Half King had sobered up. In a formal speech, he told Captain Joncaire and the French to leave the Indians' land in the Ohio and go back to Montreal.

IT RAINED AND IT RAINED AND IT RAINED. Heavy gray skies hung low over the wilderness. They rode their horses through dark forest groves and misty open meadows. Roughly sixty miles of travel lay between them and Fort Le Boeuf, at the head of Rivière Le Boeuf, where they hoped to find the French commandant. The little caravan traced the winding course of the small river northward. Horses' hooves sank in the marshy mires. They splashed through low spots. The feeder streams ran full from the rains, the high waters submerging the tall grasses that grew along the riverbank. The grass clumps bent underwater, like long beards blowing in the wind, rippling and wavering with the eddies of the stream flow.

Making camp, they unrolled thick furs or scratchy blankets or bearskins in the tents while rain pattered on the canvas. A fire leaped and hissed outside. They huddled round it, drying themselves, eating their supper. Salt pork, hardtack—a large, tough cracker made from flour—dried meat, Indian cornmeal mush, and, on days when the Indian hunters met success, fresh roasted venison or bear.

It was the Congo of its day, the Heart of Darkness. Heading into this vast wilderness of forest and swamp, river and mountain, peopled by strange tribes whose alliances you did not know, you felt at times that you were silently watched from the trees. Odd, hybrid characters of indeterminate race and origin appeared at distant villages and trading outposts—characters like Andrew Montour, who costumed himself in a mix of haute couture and animism, wearing a European coat of fine skyblue fabric, a red damask waistcoat, breeches, and stockings but circling his face with a broad ring of bear fat and paint and braiding his ears with brass wire, as one traveler put it, "like a handle on a basket."

Those who ventured here did so at their own risk, leaving behind the familiar safety of the lands over the Appalachian Mountains, the civilized havens, the provincial capitals of Philadelphia and Williamsburg along the Atlantic coast. There was much to fear, and much to gain—fortunes to be made in fur, in land—although to do so one risked losing more than one understood. A certain callousness attended life here. The blood feuds raged as passionately and the sense of honor burned as brightly as in the lands on the far side of the mountains, but bound by rules you didn't know.

This was the land into which young Washington journeyed.